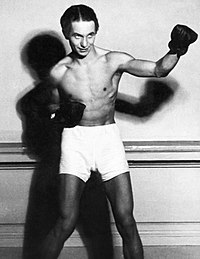

Tadeusz Pietrzykowski (Polish pronunciation: [taˈdɛ.uʂ pjɛtʂɨˈkɔfskʲi]; 8 April 1917 – 17 April 1991) was a Polish boxer, Polish Armed Forces soldier, and a prisoner at the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Neuengamme concentration camps run by the German Nazis during World War II. He was part of the first mass transport to Auschwitz in June 1940, and was transferred to Neuengamme in 1943. He is remembered as the boxing champion of Auschwitz. Pietrzykowski's life story has been the subject of several books and movies.[1][2][3][4]

| |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Nickname | Teddy |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Born | 8 April 1917 Warsaw, Kingdom of Poland |

| Died | 17 April 1991 (aged 74) Bielsko-Biała, Poland |

| Weight | 53 kg (117 lb) |

| Sport | |

| Sport | Boxing |

| Weight class | Bantamweight |

| Club | Legia Warsaw |

Early life

editPietrzykowski was born on 8 April 1917 in Warsaw[5] to father Tadeusz, an engineer, and mother Sylwina (née Bieńkowska), a teacher, both members of the Polish intelligentsia. In his youth he joined the boxing section of the Legia Warsaw club, where he trained under Feliks Stamm.[6] He received a number of positive write-ups in the interwar Polish sports press, and was nicknamed "Teddy" or "Teddi".[6] He was at the height of his sports career in the years 1936 and 1937; in 1935 his boxing section advanced to the A-rank in Warsaw, and in 1937 he qualified for the finals in the Polish Boxing Championships and became the Warsaw Champion in the bantamweight class.[7] A 1938 edition of the Polish sports magazine Przegląd Sportowy declared him "the best bantamweight boxer in Warsaw". Around that time he suffered an injury and was expelled from his school, and his boxing section was disbanded.[7][8]

Following the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, Pietrzykowski took part in the Siege of Warsaw, volunteering for a light artillery regiment.[6][9] In early 1940, following the Polish defeat, he attempted to travel to France, where the Polish Army was being reformed. He was arrested in Hungary, and deported back to Poland, where he was interrogated and tortured by the Gestapo. On 14 June 1940, he was moved from a regular prison in Tarnów to the Auschwitz concentration camp.[6] He arrived there with the first mass transport to Auschwitz concentration camp, receiving the camp prisoner number 77.[6]

Life in the camps

editIn March 1941, Pietrzykowski joined the Auschwitz resistance movement, Związek Organizacji Wojskowej, working directly under Witold Pilecki.[6] A few months later he took part in an assassination attempt against a high-ranking German officer in the camp, commandant Rudolf Höss, by helping to sabotage the saddle of Höss' horse. The assassination attempt failed, but resulted in Höss breaking a leg. The incident was classified as an accident by the Germans, and the prisoners were not punished.[6] Later, Pietrzykowski killed Höss' dog, which had been trained to attack Jewish prisoners and had killed at least one of them. The dog was cooked and eaten by the prisoners.[6] Pietrzykowski was also involved in other resistance activities, such as passing information and sabotaging labor activities.[6]

He took part in his first unofficial boxing fight in the camp in March 1941, motivated by the promise of additional food rations. The match was against Walter Dünning, a German kapo and the German middleweight vice-champion. The match was judged by Bruno Brodniewicz. The fight was inconclusive, but Pietrzykowski was considered by many to be the winner as his opponent was better fed, better rested, and had a 40-to-70 kg weight advantage. His performance in the fight gained him the approval of camp personnel and started his career as a boxer within the camp.[9][6] Although boxing matches were intended as amusement for camp personnel, the fights became popular with the prisoners as well, and Pietrzykowski's victories over German opponents or collaborators boosted morale among the inmates.[6]

He faced a number of opponents in Auschwitz, including other imprisoned Polish boxers such as Michał Janowczyk.[10] Sometimes his opponents were prisoner volunteers. Pietrzykowski tried to adjust his style to his opponents, avoiding injuring them (unless they were German kapos) and prolonging the fights for the amusement of the onlookers.[6] In particular, he tried to help the Jewish boxers he fought, recognizing that the matches were more perilous for them; in at least one case he tied on purpose, drawing a compromise between maintaining his winning streak and avoiding drawing the guards' ire to his Jewish opponent.[6] Several times he fought German opponents in fights that were considered to be particularly vicious. He was victorious against German professional boxers such as Wilhelm Maier and Harry Stein.[6] Some of his fights were more impromptu: for example, in May 1941, with permission of a guard, he challenged a prisoner who was beating another prisoner; only later did he learn that he had rescued a priest who later became Saint Maximilian Kolbe.[6]

Due to his style, which favored evasion, the Germans nicknamed Pietrzykowski the Weißer Nebel (White Fog). Boxing fights for the amusement of the German personnel took place most Sundays. While in Auschwitz, Pietrzykowski fought between 40 and 60 matches and had a long winning streak, losing only a single fight in the summer of 1942 (against a Dutch Jew and also professional boxer, middleweight champion Leen Sanders); Pietrzykowski would go on to win a later rematch between the two.[6][9] The rewards for his victories were the privileges of being allowed to choose where to work and extra food, which he often shared with other prisoners.[6] At one point, he received a proposal to sign the Volksliste, which would have enabled him to leave the camp, but he refused.[6] At another time, he was subjected to a medical experiment; he was intentionally infected with typhus by the camp medical personnel during a check-up in the camp hospital, but he survived.[6]

Some of Pietrzykowski's victories over German opponents made him enemies among German personnel, and there were rumors that he would be executed in revenge. However, in March 1943, a visiting German official, Hans Lütkemeyer of the newly opened Neuengamme concentration camp, recognized Pietrzykowski, whom he had met during a match in 1938. Lütkemeyer invited Pietrzykowski to transfer to the new camp, which he accepted. He was transferred to Neuengamme on 14 March 1943.[9][6]

In Neuengamme, he continued boxing, defeating opponents ranging from German kapos to an Italian professional boxer. As in Auschwitz, his fights were popular not just among the guards, but among the prisoners, a number of whom mentioned in their diaries that they were the cultural and sport highlight of their otherwise miserable lives in the camps. In Neuengamme, Pietrzykowski was considered undefeated. One of his most notable opponents was German-American heavyweight boxer, Schally Hottenbach, nicknamed "Hammerschlag" (Hammer Strike), whom Pietrzykowski defeated in August 1943.[6] His undefeated string, once again, irritated some Germans, and once again rumors started to spread that some German personnel were planning to murder him. However, Pietrzykowski was able to arrange a transfer for himself to another camp in Salzgitter (KZ Salzgitter-Watenstedt), where he became ill, but recovered. In total, he fought at least 20 matches in Neuengamme. His last opponent was Russian soldier Kostia Konstantinow.[6]

In March 1945, as the Eastern Front was approaching, Pietrzykowski was transferred to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. He survived there until the camp was liberated a month later, on 15 April 1945.[6]

After the war

editAfter being liberated, Pietrzykowski joined the Polish 1st Armoured Division where he organized sport activities for the soldiers.[6][11] He also sparred with other soldiers, winning his Division lightweight boxing championship in 1946.[7] In 1947, he returned to Poland, where he testified in the trial of Rudolf Höss.[6] He tried to restart his sport career, but developed illnesses[8] and his official post-war match record is 15 victories and two ties.[7]

Pietrzykowski was married three times.[7][8] In 1959 he finished his studies at the University of Physical Education in Warsaw.[11] In the 1960s, he settled in Bielsko-Biała, where he became a sport and physical education teacher, and boxing instructor.[6][7][8] He died on 17 August 1991.[6]

Remembrance

editHis life is the subject of two in-depth biographies.[a] Parts of Pietrzykowski's life, particularly his fight against Schally Hottenbach, served as the basis for a 1962 film by the Slovak director Peter Solan (Boxer a smrť - The Boxer and Death) with a script by Polish writer Józef Hen who would later write a book based on it (Bokser i śmierć, 1975).[10][12][13] Pietrzykowski's story was also featured in a movie about famous Polish boxers, Ring Wolny (2018).[14][15] Another movie about his life, The Champion, with Piotr Głowacki as the main protagonist, was announced in 2019 and was planned to premier in Poland in the autumn of 2020, but was delayed till spring 2021.[16][17][18]

In April 2020, the town council of Bielsko-Biała announced it would commemorate Pietrzykowski.[17] There had been a street named after him in Bielsko-Biała, but it closed in 2008.[8]

In May 2021, an exhibition of Pietrzykowski's paintings entitled Tadeusz Pietrzykowski – A Warrior with an Artist's Soul, was opened at the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk.[19]

His story is also featured in Andrzej Fedorowicz's 2020 historical book Gladiatorzy obozów śmierci (The Gladiators of the Death Camps).[20]

In 2021, a Łódź-based Polish rapper Basti released an album entitled Osobisty Zbiór Wartości (Personal Set of Values) featuring a song "Teddy" devoted to Pietrzykowski.[21]

See also

edit- Salamo Arouch (1923-2009), Jewish-Greek boxer imprisoned at Auschwitz, and forced to fight other internees; his story was fictionalized as Triumph of the Spirit, a 1989 biographical drama film.

- Antoni Czortek (1915-2004), Polish boxer who also fought for his life in Auschwitz.

Notes

edita ^ Joanna Cieśla and Antoni Molenda, Tadeusz Pietrzykowski “Teddy” (1917–1991) (Katowice: Towarzystwo Opieki nad Oświęcimiem, Oddział Wojewódzki, 1995); and, Bogacka, Bokser Z Auschwitz (Demart SA, 2012).[22]

References

edit- ^ "Au camp d'Auschwitz, la boxe fut aussi un moyen pour survivre". L'Express (in French). 24 December 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Teddy, le gladiateur d'Auschwitz". Le Figaro (in French). 24 December 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Langbein, Hermann (2004). People in Auschwitz. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780807828168.

- ^ Fedorowicz, Andrzej. "Gladiatorzy z obozów śmierci". Focus. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Joanna Cieślak; Antoni Molenda (1995). Tadeusz Pietrzykowski "Teddy": 1917-1991. Tow. Opieki nad Oświęcimiem, Oddz. Wojewódzki. p. 5. ISBN 9788390294216.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Bogacka, Marta (2012). "Obozowe lata Tadeusza Pietrzykowskiego – boksera, który pięściami wywalczył sobie życie". Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość (in Polish). 2 (20): 139–166. ISSN 1427-7476.

- ^ a b c d e f "TADEUSZ 'TEDDY' PIETRZYKOWSKI - JEDYNY MISTRZ WSZECHWAG KL AUSCHWITZ". www.bokser.org. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Blaut, Maciej; Płatek, Piotr (6 March 2008). "Mistrz wszechwag KL Auschwitz". Magazyn Katowice. Wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d "The Story of the Champion Who Boxed in Auschwitz to Survive". www.vice.com. 24 January 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Walki bokserskie w obozach koncetracyjnych". www.focus.pl (in Polish). 24 May 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ a b ""Bokser z Auschwitz"". dzieje.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Cyra, Adam (15 October 2007). "Bokser i śmierć". Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Józef Hen | Życie i twórczość | Artysta". Culture.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "FilmPolski.pl". FilmPolski (in Polish). Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "W Auschwitz dziadek walczył o życie pięściami". plus.gazetakrakowska.pl (in Polish). 19 October 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ ""Mistrz". Historia Polaka, który zdobył tytuł mistrza wszechwag obozu koncentracyjnego Auschwitz-Birkenau". gazetapl (in Polish). 22 January 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ a b Redakcja (4 February 2020). "Bokser z Auschwitz. Bielsko-Biała upamiętni Tadeusza Teddy'ego Pietrzykowskiego". Dziennik Zachodni (in Polish). Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Premiera "Mistrza" przełożona na 2021 rok". film.interia.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "WYSTAWA CZASOWA "TADEUSZ PIETRZYKOWSKI – WOJOWNIK O DUSZY ARTYSTY" JUŻ OTWARTA" (in Polish). Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "Pierwsza walka polskiego mistrza boksu w obozie Auschwitz. Tak rozprawił się ze sadystycznym kapo" (in Polish). Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "Basti "Teddy" – utwór i animacja o polskim bokserze z Auschwitz" (in Polish). 27 August 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Wolski, Paweł (2017). "Excessive Masculinity: Boxer Narratives in Holocaust Literature". Teksty Drugie. 2: 209–229. doi:10.18318/td.2017.en.2.13.