Tammaritu I, son of Urtak, was briefly (from 653-652 BCE)[1] a ruler in the ancient kingdom of Elam, ruling after the beheading of his predecessor Teumman in 653. He ruled part of Elam while his brother, Ummanigash (son of Urtak), ruled another.[2][3]

| Tammaritu I | |

|---|---|

| |

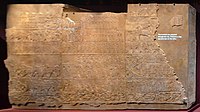

Tammaritu (behind the bow), son of Urtak, leading Assyrian troops against Teumman, king of Elam, at the Battle of Ulai. British Museum. | |

| Reign | c. 653 - 652 BCE |

| Predecessor | Teumman |

| Dynasty | Humban-Tahrid dynasty ("Neo-Elamite") |

| Father | Urtak |

Urtak, the father of Ummanigash and Tammaritu, had ruled Elam from 675 to 664, at which point he died and was succeeded by Teumman. When Teumman rose to power, Urtak's sons Ummanigash, Ummanappa, and Tammaritu escaped to Assyria in fear of Teumman,[4] and lived under Assyrian protection at Nineveh.[5] Based on his position in an Assyrian lists, Tammaritu was likely a younger son of Urtak.[6] The Assyrian Ashurbanipal, at the Battle of Ulai, killed Teumman, opening the way for the rule of Tammaritu and Ummanigash.

After the death of Teumman, the Assyrian king placed Ummanigash as "king" over the Elamite city of Madaktu, and his brother Tammaritu as "king" of Hidalu.[6] Meanwhile, Ashurbanipal faced an attempt by his brother, Shamash-shum-ukin, king of Babylon, to take over the Assyrian Empire.[6] Ummanigash joined this rebellion, sending soldiers to the aid of Shamash-shum-ukin in 652.[6] The Elamite forces were defeated, and shortly thereafter an individual by the name of Tammaritu (not the brother of Teumman) came to power in Elam,[6] likely as a result of the Elamite defeat.[7] This successor of Ummanigash is known to modern history as Tammaritu II.[1]

-

Ummanigash and Tammaritu acclaimed as rulers of Elam after the Battle of Tulliz.[8]

-

The relief in the British Museum

-

Detail

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Jane McIntosh (2005). Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 359. ISBN 978-1-57607-965-2.

- ^ Martin Sicker (2000). The Pre-Islamic Middle East. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-275-96890-8.

- ^ John Boederman (1997). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 888. ISBN 978-0-521-22717-9.

- ^ D. T. Potts. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. pp.277-8.

- ^ Paul-Alain Beaulieu (20 November 2017). A History of Babylon, 2200 BC - AD 75. Wiley. p. 280. ISBN 978-1-119-45907-1.

- ^ a b c d e D. T. Potts. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. p. 280.

- ^ John Boederman (1997). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-521-22717-9.

- ^ "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ Maspero, G. (Gaston); Sayce, A. H. (Archibald Henry); McClure, M. L. (1903). History of Egypt, Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia and Assyria. London : Grolier Society.

- ^ Maspero, G. (Gaston); Sayce, A. H. (Archibald Henry); McClure, M. L. (1903). History of Egypt, Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia and Assyria. London : Grolier Society. p. 427.

![Ummanigash and Tammaritu acclaimed as rulers of Elam after the Battle of Tulliz.[8]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/79/Khumban-Igash_acclaimed_as_King_after_the_Battle_of_Tulliz.jpg/200px-Khumban-Igash_acclaimed_as_King_after_the_Battle_of_Tulliz.jpg)

![Tongue removal and live flaying of Elamite chiefs after the Battle of Ulai, 653 BCE.[9][10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6d/Exhibition_I_am_Ashurbanipal_king_of_the_world%2C_king_of_Assyria%2C_British_Museum_%2844156996760%29.jpg/200px-Exhibition_I_am_Ashurbanipal_king_of_the_world%2C_king_of_Assyria%2C_British_Museum_%2844156996760%29.jpg)