The Tarnopol Ghetto (Polish: getto w Tarnopolu, German: Ghetto Tarnopol) was a Jewish World War II ghetto established in 1941 by the Schutzstaffel (SS) in the prewar Polish city of Tarnopol (now Ternopil, Ukraine).[1]

| Tarnopol Ghetto | |

|---|---|

Tarnopol Synagogue prior to destruction during World War II | |

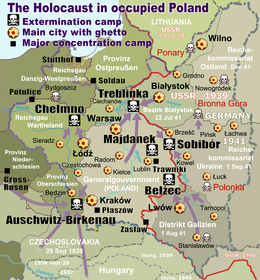

Tarnopol location during the Holocaust in Poland | |

Ternopil in modern-day Ukraine (compare with above) | |

| Location | Tarnopol, German-occupied Poland 49°20′N 25°22′E / 49.34°N 25.36°E |

| Incident type | Imprisonment, forced labor, starvation, mass killings |

| Organizations | Schutzstaffel (SS), Einsatzgruppe C, Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, Wehrmacht |

| Executions | Tarnopol cemeteries |

| Victims | 20,000 Jews |

Background

According to Polish census of 1931, Jews constituted 44% of the city's diverse multicultural makeup.[2] Tarnopol had the largest Jewish community in the area,[3] with the majority of Jews speaking Polish as their native language.[2] At the time of the Soviet invasion there were 18,000 Jews living in the provincial capital.[4]

The first week-long killing spree of 1,600–2,000 Jews occurred a few days after Tarnopol was occupied by the German army at the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union.[5][6] The ghetto was established formally two months later.[4] Tarnopol was occupied by the Wehrmacht on July 2, 1941. Several hundred Jews followed the Soviets in their hasty retreat to the east.[6] Immediately afterwards, up to 1,000 dead bodies of political prisoners murdered by the NKVD were discovered at the Tarnopol prison and 1,000 more in nearby towns. In accordance with the Nazi Judeo-Bolshevism canard, the Germans declared the Jews responsible for the Soviet atrocities.[7][8]

A pogrom broke out two days later and lasted from July 4 until July 11, 1941, with homes destroyed, synagogue burned and Jews killed indiscriminately, estimated at 1,600 (Yad Vashem)[6] at various locations including inside prison, at the Gurfein School, and at the synagogue set on fire afterwards.[9] The killing of about 1,000 Jews was done by the SS-Sonderkommando 4b attached to Einsatzgruppe C,[6] under the command of Guenther Hermann,[10] (just returning from the massacre in Łuck)[11] with another 600 Jews murdered by the Ukrainian Militia[6] – formed by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists – and renamed as the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police the following month.[12] Nearly all of their Jewish victims were men.[6] Some 500 Jews were murdered in the suburbs on the grounds of the Ternopil's Christian cemetery using weapons handed out by the German army.[13] According to interviews conducted in Ukraine by a Roman Catholic priest, Father Patrick Desbois from Yahad-In Unum, some of the victims were decapitated.[13]

Ghetto history

The German authorities ordered the creation of a Judenrat with 60 members. Teacher Marek Gottfried became its president. The Jews were summoned to police headquarters in one group, loaded onto lorries, and taken out of town to a secret execution site at Zagroble nearby.[9] In early August 1941 the Jews of Tarnopol were ordered to wear a Star of David and mark their homes with it.[6] A 'new' Judenrat was formed by the Nazis soon after the wave of massacres, without disclosing the fate of its original members, and ordered to pay a ransom of 1.5 million rubles. Gustaw Fischer was appointed head of the Judenrat.[9]

In September 1941, the German occupation authorities under Gerhard Hager announced the creation of a designated Jewish ghetto in the city around the Old Square and the Market Square Minor, in a derelict district that occupied mere 5 percent of the metropolitan area. Population density in the ghetto was tripled, with 12,000–13,000 Jews put in it. Death penalty was introduced for leaving the ghetto illegally, and all food allowances rationed.[9] Within a year the conditions in the ghetto became so bad that in the winter of 1941–42 the Judenrat began burying the corpses in mass graves for sanitation concerns due to rampant mortality rates.[6] Satellite labour camps for Jewish slave workers were established by the Germans in Kamionka, Podwołoczyska, Hluboczka, and in Zagroble.[4]

Roundups and ghetto liquidation

The first ghetto liquidation action was perpetrated on August 31, 1942,[9] not long after the Final Solution was set in motion.[6] By that time, the Bełżec extermination camp northwest of Tarnopol was already working at full throttle.[14] Some 3,000–4,000 Jews were rounded up and locked in cattle cars, with no water.[9] The transport remained at the station for two days with all victims crying out for help; meanwhile, another cattle train arrived with Polish Jews from the ghettos in Zbaraż and Mikulińce. The two trains were connected at the station as one Holocaust transport to Bełżec with at least 6,700 victims dying inside from suffocation and thirst.[9]

The next Holocaust train was assembled on November 10, 1942.[9] Some 2,500 Jews were rounded up and marched to the station, with a small Ukrainian orchestra playing on their departure to Bełżec. The ghetto area was greatly reduced; a part of it, turned into a labour camp.[9] Between August 1942 and June 1943 there were five "selections" that decimated the Jewish prisoner population of Tarnopol.[6] The camps were liquidated as the last.[9] The victims were sent in Holocaust trains to the extermination camp at Bełżec, but also massacred in shooting actions at Petrykowo,[9] or Petrykow-Wald, with the assistance of Ukrainian policemen. Estimated 2,500 Jews perished there.[15] A few hundred Jews from Tarnopol and its vicinity attempted to survive by hiding within the town limits. Many were denounced by Ukrainian nationalists, including some 200 people shortly before the Soviets took over the area in 1944.[6]

A number of Jews survived the Holocaust by hiding with the Poles.[6] Righteous Among the Nations who helped Tarnopol Ghetto's Jews included the Regent family[16] and the Misiewicz family.[17] A monument in memory of the Holocaust victims was erected in Ternopil at Petrikovsky Yar in 1996.[18]

See also

- Stanisławów Ghetto in a provincial capital of occupied eastern Poland

- Łuck Ghetto, at another regional capital in the Kresy macroregion

- Słonim Ghetto in Nowogródek Voivodeship

References

- ^ Joshua D. Zimmerman (2015), The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939–1945. Cambridge University Press via Google Books. "The Provinces of Poland on the Eve of World War II," pp. xviii, 278, 328, 347. At Teheran (1943) Churchill told Stalin that he wished to see a new Poland "friendly to Russia". Stalin replied that nevertheless, he considered the annexation of Eastern Poland "just and right" only along the frontiers of the Nazi-Soviet invasion of 1939.[p. 351]

- ^ a b Central Statistical Office (Poland), Drugi Powszechny Spis Ludności. Woj.tarnopolskie, 1931. PDF file, 21.09 MB. The complete text of the Polish census of 1931 for the Tarnopol Voivodeship, page 59 (select, drop-down menu). Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ Wydarzenia 1931 roku. Historia-Polski.com. Compendium of cities in the Republic with Jewish populations exceeding 12 thousand (Wykaz miast RP z populacją żydowską powyżej 12 tysięcy). Tarnopol: 14.000 czyli 44% ludności.

- ^ a b c Robert Kuwałek; Eugeniusz Riadczenko; Adam Marczewski (2015). "Tarnopol". History - Jewish community before 1989. Translated by Katarzyna Czoków and Magdalena Wójcik. Virtual Shtetl. pp. 3–4 of 5. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Aharon Weiss (2015). "Tarnopol (Rus. Ternopol)". Jewish Families of Ternopil (Tarnopol). Geni.com. Holocaust and Postwar Periods. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The Righteous Among the Nations – Featured Stories: Tarnopol Historical Background". Yad Vashem. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014.

- ^ Ferguson 2006, p. 419.

- ^ Piotrowski 1998, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Robert Kuwałek; Eugeniusz Riadczenko; Adam Dylewski; Justyna Filochowska; Michał Czajka (2015). "Tarnopol". Historia - Społeczność żydowska przed 1989 (in Polish). Virtual Shtetl (Wirtualny Sztetl). pp. 3–4. of 5 pages. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ IDs of SS-Men. The SS & Polizei section. Axis History Forum. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Ronald Headland (1992), Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941–1943. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, pp. 79, 125. ISBN 0-8386-3418-4.

- ^ Symposium Presentations (September 2005). "The Holocaust and [German] Colonialism in Ukraine: A Case Study" (PDF). The Holocaust in the Soviet Union. The Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 15, 18–19, 20 in current document of 1/154. Direct download 1.63 MB. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 16, 2012. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- ^ a b Cnaan Liphshiz, Talking with the willing executioners. Haaretz.com, May 18, 2009. A horrific page of history unfolded last Monday in Ukraine. It concerned the gruesome and untold story of a spontaneous pogrom by local villagers against hundreds of Jews in a town [now suburb] south of Ternopil in 1941. Not one, but five independent witnesses recounted the tale, recalling how they rushed to a German army camp, borrowed weapons and gunned down 500 Jews inside the town's Christian cemetery. One of them remembered decapitating bodies in front of the church.

- ^ Browning, Christopher (2000). Nazi Policy, Jewish Workers, German Killers. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 052177490X.

substitution.

- ^

- "Tarnopol region - Online Guide of Murder Sites of Jews in the Former USSR", Yad Vashem, Tarnopol District, Poland, Petrykow Area,

Shootings near Petrykow village began in mid July 1941 and concluded on 1-2 August 1943.

- C. F. Rüter; D. W. de Mildt, eds. (1968), "Andere Massenvernichtungsverbrechen im Wirkungsbereich der Sipo-Außenstelle Tarnopol wurden vom LG Stuttgart ermittelt, lfd. Nr. 634" [Other crimes of mass extermination committed within range of the Sipo branch office Tarnopol; investigated LG Stuttgart, Serial number 634], Volume XXIV: Proceedings No.634 - 639 (1966), Westdeutsche Gerichtsentscheidungen–Justiz und NS-Verbrechen [West German court decisions – Justice and Nazi crimes] (in German), Amsterdam: Foundation for scientific research into National Socialist crimes, (Gerichtsentscheidungen LG Stuttgart vom 15.07.1966, Ks 7/64; BGH vom 07.05.1968, 1 StR 601/67 [Court decisions: LG Stuttgart dated July 15, 1966, Ks 7/64; BGH dated May 7, 1968, 1 StR 601/67]) – via JuNSV Project:

- English translation — of excerpt (case title and decision details) by JuNSV Project. Archived 2016-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "Tarnopol region - Online Guide of Murder Sites of Jews in the Former USSR", Yad Vashem, Tarnopol District, Poland, Petrykow Area,

- ^ Piotr Żulikowski (January 2011). "Rodzina Regentów" [The Regent Family]. Przywracanie Pamięci (The Return of Memory). Polscy Sprawiedliwi (Polish Righteous). pp. 1 of 3. In Polish, with Google link to optional webpage translation in English.

- ^ Wojciech Załuska (October 2010). "Rodzina Misiewiczów" [The Misiewicz Family]. Przywracanie Pamięci (The Return of Memory). Polscy Sprawiedliwi (Polish Righteous). p. 1. In Polish. Israel Gutman, Księga Sprawiedliwych wśród Narodów Świata.

- ^ В Тернополе осквернили памятник жертвам Холокоста [Monument to Holocaust victims in Ternopil desecrated] (in Russian). Евроазиатский Еврейский Конгресс. 2012-09-25. Archived from the original on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 12 September 2015. The USSR officially ceased to exist on 31 December 1991.

Further reading

- Ferguson, Niall (2006). The War of the World: History's Age of Hatred. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0713997087. Hardcover – via Google Books.

Operations of Einsatzgruppe C in eastern Poland.

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1998). Poland's Holocaust. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2913-4 – via Google Books.