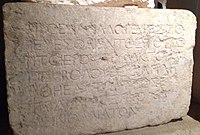

The Temple Warning inscription, also known as the Temple Balustrade inscription or the Soreg inscription,[2] is an inscription that hung along the balustrade outside the Sanctuary of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Two of these tablets have been found.[3] The inscription was a warning to pagan visitors to the temple not to proceed further. Both Greek and Latin inscriptions on the temple's balustrade served as warnings to pagan visitors not to proceed under penalty of death.[3][4]

| Temple Warning Inscription | |

|---|---|

The inscription in its current location | |

| Material | Limestone |

| Writing | Greek |

| Created | c. 23 BCE – 70 CE[1] |

| Discovered | 1871 |

| Present location | Istanbul Archaeology Museums |

| Identification | 2196 T |

A complete tablet was discovered in 1871 by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau, in the ad-Dawadariya school just outside the al-Atim Gate to the Temple Mount, and published by the Palestine Exploration Fund.[1][5] Following the discovery of the inscription, it was taken by the Ottoman authorities, and it is currently in the Istanbul Archaeology Museums. A partial fragment of a less well made version of the inscription was found in 1936 by J. H. Iliffe during the excavation of a new road outside Jerusalem's Lions' Gate; it is held in the Israel Museum.[1][6][7]

Inscription

editTwo tablets have been found, one complete, and the other a partial fragment with missing sections, but with letters showing signs of the red paint that had originally highlighted the text.[4] It was described by the Palestine Exploration Fund in 1872 as being "very nearly in the words of Josephus".[8][9][10]

The inscription uses three terms referring to temple architecture:[11]

Translation

editThe tablet bears the following inscription in Koine Greek:

| Original Greek | In minuscules with diacritics | Transliteration[12] | Translation[13] |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΜΗΘΕΝΑΑΛΛΟΓΕΝΗΕΙΣΠΟ

ΡΕΥΕΣΘΑΙΕΝΤΟΣΤΟΥΠΕ ΡΙΤΟΙΕΡΟΝΤΡΥΦΑΚΤΟΥΚΑΙ ΠΕΡΙΒΟΛΟΥΟΣΔΑΝΛΗ ΦΘΗΕΑΥΤΩΙΑΙΤΙΟΣΕΣ ΤΑΙΔΙΑΤΟΕΞΑΚΟΛΟΥ ΘΕΙΝΘΑΝΑΤΟΝ |

Μηθένα ἀλλογενῆ εἰσπο-

ρεύεσθαι ἐντὸς τοῦ πε- ρὶ τὸ ἱερὸν τρυφάκτου καὶ περιβόλου. Ὃς δ᾽ ἂν λη- φθῇ, ἑαυτῶι αἴτιος ἔσ- ται διὰ τὸ ἐξακολου- θεῖν θάνατον. |

Mēthéna allogenē eispo[-]

reúesthai entòs tou pe[-] rì tò hieròn trypháktou kaì peribólou. Hòs d'àn lē[-] phthē heautōi aítios és[-] tai dià tò exakolou[-] thein thánaton. |

No stranger is to enter

within the balustrade round the temple and enclosure. Whoever is caught will be himself responsible for his ensuing death. |

The identity of the hypothetical stranger/foreigner remains ambiguous. Some scholars believed it referred to all gentiles, regardless of ritual purity status or religion. Others argue that it referred to unconverted Gentiles since Herod wrote the inscription. Herod himself was a converted Idumean (or Edomite) and was unlikely to exclude himself or his descendants.[14]

Forgeries

editSeveral forgeries were promptly prepared following the 1871 discovery.[15] Clermont-Ganneau was shown a similar artifact at the Monastery of St Saviour, which was later shown to be a forgery created by Martin Boulos.[16]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae, Jerusalem, Part 1, Walter de Gruyter, 2010, ISBN 9783110222203, page 42

- ^ Magness, Jodi (2012). The Archaeology of the Holy Land: From the Destruction of Solomon's Temple to the Muslim Conquest. Cambridge University Press. p. 155.

- ^ a b Bickerman, Elias J. "The Warning Inscriptions of Herod's Temple"' The Jewish Quarterly Review, vol. 37, no. 4, 1947, pp. 387–405.

- ^ a b Llewelyn, Stephen R., and Dionysia Van Beek. "Reading the Temple Warning as a Greek Visitor". Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Period, vol. 42, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1–22.

- ^ Charles Clermont-Ganneau: Une stèle du temple de Jérusalem. In: Revue archéologique. Band 23, 1872, S. 214–234 (online), 290–296 (online): quote: "...on s'engage sous une assez longue voûte ogivale, à l'extrémité de laquelle on remarque, à main droite, la porte Bâb-el-Atm, par où l'on a sur la mosquée d'Omar une merveilleuse échappée. A main gauche, et faisant face à cette porte, on voit, donnant sur un petit cimetière musulman, une sorte de baie grillée, pratiquée dans un mur construit en gros blocs à bossages (à forte projection) et flanqué d'une espèce de contrefort du même appareil. Le cimetière ne contient que quelques tombes de cheikhs morts en odeur de sainteté, et appartenant probablement à la Médrésé (école supérieure) qui s'élevait jadis derrière ce mur d'aspect si caractéristique... J'arrivai ainsi jusqu'à la Médrésé, où j'entrai, introduit par un des habitants qui fit d'abord quelques difficultés à cause de la présence du harim, mais dont il ne me fut pas malaisé de faire taire les scrupules. Une fois dans la vaste cour décrite plus haut, je fixai.d'abord mon attention sur les deux tarîkhs arabes, qui, du reste, sont déjà connus, puis je commençai, suivant la méthode qui m'a toujours réussi, à examiner de près, et pour ainsi dire bloc par bloc, les constructions adjacentes. Arrivé à la petite voûte faisant face au grand liwân, je découvris tout à coup, presque au ras du sol, deux caractères grecs gravés sur un bloc formant l'angle du mur sur lequel reposait la petite voûte: 0 C'était évidemment la fin d'une ligne qui s'enfonçait verticalement dans la terre. Frappé du bel aspect graphique de ces lettres, je commençai, avec l'aide d'un des musulmans habitant la Médrésé, à gratter et creuser pour dégager quelques autres caractères. Après quelques minutes de travail, je vis apparaître un magnifique 1 de la belle époque classique, comme jamais il ne m'avait été donné d'en relever dans les inscriptions que j'avais découvertes jusqu'à ce jour à Jérusalem. Évidemment, j'avais affaire à un texte important par sa date, sinon par son contenu; je me remis à l'œuvre avec une ardeur facile à comprendre. Le musulman qui m'aidait, s'étant, sur ces entrefaites, procuré une fas ou pioche chez un voisin, la fouille put être poussée plus activement. Je vis successivement apparaître les lettres El, dont la première, l'epsilon, confirmait la valeur épigraphique du 2; puis le mot , étranger, que je reconnus sur-le-champ. Ce mot me remit aussitôt en mémoire le passage de Josèphe qui parle d'inscriptions destinées à interdire aux Gentils l'accès du Temple; mais je n'osais croire à une trouvaille aussi inespérée, et je m'appliquai à chasser de mon esprit ce rapprochement séduisant, qui continua toutefois de me poursuivre jusqu'au moment où j'arrivai à la certitude. Cependant la nuit était venue; je dus, pour ne pas exciter les soupçons des habitants de la Médrésé par une insistance inexplicable pour eux, suspendre le travail. Je fis reboucher le trou et je partis très-troublé de ce que je venais d'entrevoir. Le lendemain, de grand matin, je revins avec les instruments nécessaires, et je fis attaquer vigoureusement la fouille. Après quelques heures d'un travail que je ne perdais pas de l'œil, et pendant lequel je vis naître un à un et copiai avec des émotions croissantes les caractères de la belle inscription que j'ai l'honneur de soumettre aujourd'hui à l'Académie, le bloc et toute sa face écrite étaient mis au jour."

- ^ Israel Museum, ID number: IAA 1936-989

- ^ Iliffe, John H. (1936). "The ΘΑΝΑΤΟΣ Inscription from Herod's Temple". In Palestine. Department of Antiquities (ed.). Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. Vol. 6. Government of Palestine. pp. 1–3.

During work on the construction of a new road outside St. Stephen's Gate, Jerusalem, by the Municipality of Jerusalem, during December 1935, the remains of a vaulted building of late Roman or Byzantine date were found. Beneath this building was an unpretentious tomb-chamber, cut in the rock, with the (shallow) graves excavated in the floor; it was approached by a stairway in the familiar manner and yielded a number of pottery lamps of a mid-fourth-century A.D. type.' An apparently rebuilt wall belonging to the vaulted building (itself evidently later than the fourth-century tomb below) yielded a fragment of a stone bearing a Greek inscription, which, on examination, proved to be a second copy of the Greek text of the stelae erected around the inner court of the Temple of Herod, forbidding foreigners, or Gentiles to enter, on pain of death... It is possible that this second inscription may have been intended for a less conspicuous position than, say, the Clermont-Ganneau copy, and have been, accordingly, assigned to an inferior workman... The only plausible explanation would seem to be that suggested above for our Temple inscription, i.e. that it was placed inconspicuously, and therefore no one cared.

- ^ Palestine Exploration Fund (1872). Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. Published at the Fund's Office. pp. 121–.

- ^ "Josephus: Of the War, Book V". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

Upon it stood pillars, at equal distances from one another; declaring the law of purity, some in Greek and some in Roman letters; that no foreigner should go within that sanctuary. For that second [court of the] temple was called the sanctuary: and was ascended to by fourteen steps from the first court.

- ^ DE LATINISMEN IN HET GRIEKS VAN HET NIEUWE TESTAMENT, p.15: διὰ τούτου προϊόντων ἐπὶ τὸ δεύτερον ἱερὸν δρύφακτος περιβέβλητο λίθινος, τρίπηχυς μὲν ὕψος, πάνυ δὲ χαριέντως διειργασμένος: ἐν αὐτῷ δὲ εἱστήκεσαν ἐξ ἴσου διαστήματος στῆλαι τὸν τῆς ἁγνείας προσημαίνουσαι νόμον αἱ μὲν Ἑλληνικοῖς αἱ δὲ Ῥωμαϊκοῖς γράμμασιν μηδένα ἀλλόφυλον ἐντὸς τοῦ ἁγίου παριέναι (BJ 5.2.2, §193-194) [transliterated: diá toútou proïónton epí tó défteron ierón drýfaktos perivévlito líthinos, trípichys mén ýpsos, pány dé chariéntos dieirgasménos: en aftó dé eistíkesan ex ísou diastímatos stílai tón tís agneías prosimaínousai nómon ai mén Ellinikoís ai dé Romaïkoís grámmasin midéna allófylon entós toú agíou pariénai]; Also at Perseus [1]

- ^ Bickerman, 1947, pages 387–389: "To begin with, there are three terms referring to the architectural complex of the Temple. Το ίερόν, 'holy place', is the designation of the consecrated area, to which the fore-court led. This area was called by the Jews 'sacred', mikdash (הַמִּקְדָּשׁ). The word ίερόν was common in this sense in Greek and applied to pagan cults. For this reason it was avoided by the Alexandrian translators of the Scripture who use the term το άγιον in referring to the Temple of Jerusalem. But after the Maccabean victory, the Jews had less scruples about using a technical term from Greek heathenism. On the other hand, the word το άγιον which had become fashionable for Oriental holy places, was no longer a distinctive term in Herod's time. Accordingly, Philo and Josephus use both words, ίερόν and άγιον to designate the Temple of Herod. The περίβολος was the wall which encompassed the holy terrace within the outer court. Josephus, Philo and the Septuagint use this Greek word, technical in this connotation, to describe the enclosure of the Temple. The τρύψακτος, the Soreg in the Mishna, was a stone barrier which stretched across the outer court to protect the flights of stairs leading up to the inner court. As we said, the warning inscriptions were fixed on this rail."

- ^ Note: The original text is written in scriptio continua; the "[-]" symbol in the transliteration represents the Greek words which are broken across two lines

- ^ Discovery of a Tablet from Herod's Temple

- ^ Thiessen, Matthew (2011). Contesting Conversion: Genealogy, Circumcision, and Identity in Ancient Judaism and Christianity. Oxford University Press. pp. 87–110. ISBN 9780199914456.

- ^ Cadbury, Henry J. (1 October 2004). The Book of Acts in History. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-1-59244-915-6.

It was so satisfactory that skilful natives promptly forged several duplicates

- ^ "Quarterly statement | Palestine Exploration Fund, 1884". 1869. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

External references

edit- Clermont-Ganneau, Charles Simon (30 May 1871). "Discovery of a Tablet from Herod's Temple" (PDF). Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 3 (3): 132–134. doi:10.1179/peq.1871.013. Retrieved 2018-02-27.

Google books reference at [2]

{{cite journal}}: External link in|quote= - Dr. Carl Rasmussen. "Holy Land Photos". holylandphotos.org. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Cotton, H. (2010). CIIP. De Gruyter. p. 42. ISBN 9783110222197. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Millard, Alan, Discoveries from the Time of Jesus. Oxford: Lion Publishing, 1990.

- Roitman, Aldopho, Envisioning the Temple, Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 2003.

- Elias J. Bickerman, "The Warning Inscriptions of Herod's Temple," The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Ser., Vol. 37, No. 4. (Apr., 1947), pp. 387–405.

- Matan Orian, "The Purpose of the Balustrade in the Herodian Temple," Journal for the Study of Judaism 51 (2020), pp. 1–38.