The Thái Nguyên uprising (Vietnamese: Khởi nghĩa Thái Nguyên) in 1917 has been described as the "largest and most destructive" anti-French rebellion in Vietnam (then part of French Indochina) between the Pacification of Tonkin in the 1880s and the Nghe-Tinh Revolt of 1930–31.[1] On 30 August 1917, an eclectic band of political prisoners, common criminals and insubordinate prison guards mutinied at the Thái Nguyên Penitentiary, the largest one in the region. The rebels came from over thirty provinces and according to estimates, involved at some point roughly 300 civilians, 200 ex-prisoners and 130 prison guards.[2]

| Thái Nguyên uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of French Indochina | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The initial success of the rebels was short-lived. They managed to control the prison and the town's administrative buildings for six days, but were all expelled on the seventh day by French government reinforcements.[3] According to French reports 107 were killed on the colonial side and fifty-six on the anti-colonial, including Quyến.[4] French forces were not able to pacify the surrounding countryside until six months later.[5] Cấn reportedly committed suicide in January 1918 to avoid capture.[6] Both Quyến and Cấn have since been accorded legendary status as nationalist heroes.[7]

Background

editThe Thái Nguyên area had already seen resistance from men such as Đề Thám (1858–1913). David Marr characterises earlier traditional anti-colonial rebellions before the Thái Nguyên uprising such as the Can Vuong movement (Save the King) as being led by scholar-gentry whose followings were limited to members of their own lineages and villages.[8] Leaders of these movements were ineffective in mobilising the general population beyond the scope of their influence, and in liaison and coordinating military or strategic activities on a wider scale in other provinces and regions. Marr argues that the generation of anti-colonial Vietnamese leaders Phan Bội Châu and Phan Châu Trinh after 1900 succeeded in raising questions of long-term modernization and Westernization when they were disillusioned with the mandarin class whose collaboration with the French perpetuated its rule.[9] This generation then looked towards outward influences such as the Đông Du Movement (where Lương Ngọc Quyến, a protagonist of the Thái Nguyên uprising, was a participant) for alternatives. As the Thái Nguyên uprising occurred in the same period of analysis, the goals of the uprising could be situated amidst this desire for change, whilst still searching for a 'modern' Vietnamese national-consciousness and identity. According to Zinoman, the Thái Nguyên Rebellion was especially noteworthy due to the role which prisons, a product of the colonial era, played in bringing together men from different walks of life to unite for a common purpose.[10]

Sequence of events

editWhile imprisoned in Thái Nguyên, Quyến got to know that Cấn, one of the Vietnamese sergeants in the local garrison, had considerable experience operating in the Thai Nguyen area and had been plotting an uprising for years.[11] Quyến convinced Cấn that if an uprising was sparked, reinforcements will arrive to support the rebellion. They aborted two plots to rebel in May and July 1917 for unclear reasons. For the third attempt, the plotters decided to strike after hearing rumours that some of them were to be transferred.[12] On August 30, 1917, Vietnamese guards first assassinated M. Noel, the Brigade Commander. While Cấn asked roughly 150 guards assembled in the barracks to join in the rebellion, another group released 220 prisoners in the penitentiary. Cấn discussed and agreed with Quyến's strategy to hold the town until reinforcements arrive.[13] The rebels then seized weapons from the provincial arsenal, smashed the communication equipment, plundered the provincial treasury, took up strategic positions in the town,[14] established a fortified perimeter and executed French officials and local collaborators.

On the second day, the rebels went out to the streets of Thái Nguyên and announced a proclamation appealing to the population to support a general uprising.[15] An estimated 300 poor civilians joined roughly 200 ex-prisoners and 130 guards, and the rebels were divided into two battalions.[16]

For the next five days, the rebels defended Thái Nguyên against heavy French artillery attacks. Following a French bombing on September 4, the rebels retreated into the countryside after suffering heavy casualties amidst chaos. Quyến was found dead, apparently having been killed in action, while Cấn fled to the Tam Đảo Mountains with some rebels and eluded their pursuers. Months later, in January 1918, Cấn reportedly committed suicide to avoid capture. In French accounts, Cấn's buried corpse was found through an informant/defector named Si who claimed to have killed Can so as to be pardoned by the French.[17] Bent on convincing the Vietnamese populace that revolt was futile, the French were meticulous in tracking down the rebel leaders and claimed only five men eluded "justice".[18]

Participants

editPrison guards

editLeader of the rebel guards Trịnh Văn Cấn was the son of an impoverished rural labourer from mountainous Vinh-Yen province. Cấn joined the Garde Indigene (native gendarmerie) as a youth and served his entire adult life on the remote Tonkinese frontier guarding prisoners and fighting bandits for the French.[19] According to historian Tran Huy Lieu,[20] Cấn's rebellious tendencies were shaped by his admiration of Đề Thám, having failed to track down Đề Thám's bandit gang in the mountainous and forestry terrain in Tonkin. Cấn's father had reportedly participated in the Cần Vương movement in the 1880s. Cấn reportedly contemplated an uprising for years.[21] He spotted the opportunity when the French had grown preoccupied with the war in Europe.

Political prisoners

editThe leading Vietnamese anti-colonial party of the early 20th century was the Vietnam Restoration League (VNRL) (Việt Nam Quang phục Hội) founded by Phan Bội Châu in 1912. VNRL was involved in several anti-colonial attacks including the Duy Tan plot, a failed attempt to revive the monarchist insurgency.[22] French suppression of VNRL led to influx of political activists into the colonial prison system. Amongst other VNRL figures held in Thái Nguyên, such as Nguyen Gia Cau (Hoi Xuan), Vu Si Lap (Vu Chi) and Ba Con (Ba Nho)[23] Quyến was the most prominent as he was the eldest son of the reformist mandarin Lương Văn Can and the first Vietnamese participant in the Đông Du Movement.[24] Due to his conviction of involvement in a 1913 bombing attack at Phu Tho, Quyến had been sentenced to hard labor for life and transferred to the Thái Nguyên penitentiary in July 1916. Quyến played a crucial role in the rebellion's execution. First, Cấn deferred to him on military strategy to undertake upon the outbreak of the uprising. Second, Quyến probably provided ideological direction for the rebellion as he was likely the author of the rebellion's proclamation that appealed to popular imaginings of Vietnamese nationalist histories whose symbolic references were characteristic of VNRL discourse. These include the notions that Vietnamese nation descended from "a race of dragons and fairies", Vietnamese landscape as fertile and "covered with magnificent mountains", Vietnam's long history (4000 years), dynasties rule and sacrifices expended "in order to maintain possession of this land".[25] During the rebellion, the rebels hoisted the VNRL flag (five-star red and yellow flag) in the barracks and banners around town proclaimed "Annamese Armies Will Reclaim the Country".[26] Various visual symbols (flags, banners, armbands) displayed by the rebels indicated the uprising's close link to VNRL.

Followers of Đề Thám

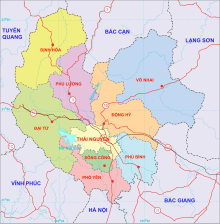

editThái Nguyên is located in the middle region of Tonkin and vulnerable to frontier banditry given its proximity to the poorly policed Sino-Vietnamese border.[27] Its mountainous topography also provided shelter and refuge for fugitives, smugglers, brigands and military deserters. The area had been the focus of resistance since the days when Đề Thám and his brigands had been active.[28] Unable to control the banditry that plagued the frontier, Vietnamese officials allied with powerful local bandit chiefs to control the smaller rivals and maintain civil order. The French assumed power in Tonkin in 1884 and collaborated with Luong Tam Ky, leader of the Yellow Flags who took twenty years to catch and kill Đề Thám.[29] Given the history of banditry in the middle region, the penal population of Thái Nguyên consisted mainly of gang members and rural brigands. Dozens of Đề Thám's followers were imprisoned at Thái Nguyên. One notable lieutenant of Đề Thám, Nguyen Van Chi (Ba Chi) played an important role in the rebellion, having led one of the battalions of the rebels. These persons had intimate knowledge of the local terrain and were used to hit-and-run tactics of banditry.

Petty criminals and civilian rebels

editIn Thái Nguyên, French companies discovered coal fields and zinc deposits and encountered difficulty in recruiting a local labour force. Transient workers from China became an erratic substitute for employment working at the local mines. Employment contracts were unstable and this in turn was linked to the growth in criminal activities amongst many ex-mine workers and many of them landed up in the Thái Nguyên prison. In the rebellion, roughly three hundred townspeople voluntarily joined with rebels. This group of civilian rebels were believed to be from the most destitute inhabitants of the province (petty criminals, day-labourers, etc.) prone to persuasion of illegal pursuits and rebellion for survival.[30]

Causes

editThe ill-disciplined prison

editIn Peter Zinoman's study of the colonial prison system in Vietnam (1862–1940),[31] he situates prisons as decentralized and autonomous institutions ran in different territories in Annam, Tonkin, Cochinchina, Cambodia and Laos due to different legal and administrative frameworks, low budgets, and unprofessional staff (divided into small European administrative elite and a large corps of Vietnamese warders) running the prisons. Zinoman argues that the colonial prison was ill-disciplined. The rehabilitative orientation within colonial punishment was absent as there was no discernible effort to reform the prisoners by discipline or provision of "total care".[citation needed]

Prisoners experienced communal living and social mixing, with little segregation premised on a classificatory and differentiating system.[32] With the rise in prisoner population including hardened criminals, the French authority upgraded the Thái Nguyên prison to a penitentiary but due to budgetary constraints and other factors, the prison institution at Thái Nguyên functioned as a provincial prison and penitentiary simultaneously. The majority of prisoners, regardless of their length of sentences, were not separated but housed in a single communal ward, except for some solitary cells housing especially dangerous convicts like Quyến. Despite recognising the flaws of institutional design of the penitentiary, the French did not undertake the necessary rectifications.[citation needed]

The prison experience encompassed living in squalid, unhygienic quarters plagued that drove up rates of infections and mortality, and backbreaking prisoner labour that could be life-threatening and subjection to abuse by guards. Under such adverse conditions, Zinoman argues the incarceration experience intensified prisoners' sensations of being interconnected, built strength and confidence of character, and the will to fight against the colonial state responsible for this injustice. In Thái Nguyên, all prisoners were subjected to the brutal regime of forced and dangerous labour of building roads and construction of public works, unsanitary conditions, abuses and beatings resulting in a high number of deaths. Colonial records show a medical report that compared the number of deaths in colonial penal institutions during the five-year period (1908–1912) and there were more prisoners who died at Thái Nguyên (332) than elsewhere except for in Nam Dinh (355).[33] This fostered a shared predicament and desperation amongst prisoners that rebellion was believed to be the only chance of escape from brink of death in the penitentiary.[34]

Provincial resident Darles

editDarles was a notorious autocrat and much-hated official[35] who terrorised the prisoners, guards and native civil servants in the penitentiary during his three-year service in the province. He was sadistically brutal, hitting the natives and punishing prisoners at will for slight reasons. His indiscriminate violent treatment of his staff drew the guards towards the prisoners in their common hatred of Darles and the administration. At the start of the rebellion, a group of guards had tried to capture Darles from his office and house but was unsuccessful.[citation needed]

French versus Vietnamese accounts of the uprising

editAfter the rebellion, different interpretations of the event were presented by the French and the Vietnamese, reflecting their respective agendas.[36] French accounts of the rebellion showed the political imperatives of the state, rather than explaining the causes and character of the Thái Nguyên uprising, when they did not account for the role and motivations of the participants behind the uprising including the civilians, political prisoners, common criminals and prison guards. In attributing the cause of the rebellion to individuals, the French tried to absolve the colonial responsibility for the rebellion while the Vietnamese account tried to promote the tradition of national heroism through the personal achievement of Sergeant Cấn.

Darles tried to present the rebellion as a revolutionary movement to divert attention from his brutal administration of the penitentiary. Commandant Nicolas of the Garde Indigene downplayed the movement's political character so as to preserve the reputation of his corps as essentially loyal and trusted, but were 'forced' to rebel due to the harsh local conditions or tactics of intimidation. The metropole, on the other hand, desired to downplay any anxieties of the 'native treachery' of the French population during the First World War.[37] French Governor General Sarraut tried to control the press in portraying the event as 'local' and having no widespread political reach and conspiracy. Sarraut tried to paint the event as the political prisoners having ridden on the guards' disgruntlement with local conditions – i.e., the collaboration was more opportunistic than having common grounds of anti-colonialism. This is in spite of the evidence that the rebellion involved participants from various social classes, had support from hundreds of civilians, and used visual symbols (such as armbands and flags) and a proclamation demanding the end of the French rule.[citation needed]

Darles was portrayed in French records to be the primary reason for the revolt. Sarraut made efforts at political damage control; he wanted to protect the reputation of his officials and invalidate an impression that colonial administrators were brutal. Sarraut nevertheless attributed the cause of the uprising to Darles' acts of violence against the guards. The rebellion was portrayed as a desperate and impulsive act of self-preservation rather than seditious plotting – it was a reflex reaction rather than a subversive plot carefully planned by the guards. To diffuse responsibility for the flaws on the penitentiary's design, Sarraut claimed the First World War had disrupted the plan to tackle overcrowding in Thái Nguyên by deporting political prisoners to penal colonies elsewhere.[38]

Tran Huy Lieu presents a different reconstruction of the event. Instead of underlining the Darles' leading role for triggering the uprising, Lieu highlights the profound anti-colonial inclinations of Sergeant Cấn and paints him as an active agent who plotted secretly against the French state. Lieu's account of Cấn as a humble, kind-hearted and strong fighter, shows a typically celebrated Vietnamese revolutionary heroism. Cấn is described as 'very courageous', 'a natural commander' and skilled martial leader, dressed simply, mild mannered and disapproved of the excesses of battle (i.e. plunder, rape of women etc.).[39]

While Peter Zinoman arguably provides a most comprehensive account (in English) on the Thái Nguyên uprising, he acknowledged there remained information gaps on the episode.[40] For instance, it was less clear who initiated and plotted the uprising, the rebels' hierarchy of command and control, and whether participants were persuaded or intimidated into joining the rebellion. Despite the gaps, Zinoman argued one could discern the existence of communications between Cấn and Quyến, inclusive decision making involving other participants, sense of comradeship transcending class and regional divisions resembling modern political nationalism.[citation needed]

Aftermath

editBlurring the lines between traditional and modern anti-colonial rebellions

editDavid Marr had contextualised the occurrence of the Thái Nguyên uprising in a period where the scholar-gentry anti-colonial Vietnamese leaders were grappling with the pressures of modernizing and strengthening the Vietnamese state while Vietnam was still under colonial rule, and trying to search for a 'modern' Vietnamese national-consciousness and identity. Peter Zinoman elaborated on the above analysis and argued that the Thai-Nguyen uprising could be considered an important transition within the history of anti-colonialism in French Indochina as it was different from the earlier 'traditional' anti-colonial efforts that were organised locally.[41] As the rebels in Thái Nguyên uprising came from over thirty provinces and represented a wider cross-section of society of various classes, the event was marked to be significant in having 'modern' elements of having transcended the social and regional limitations that hampered the development of earlier movements. Coordinated action based on vertical and horizontal alliances within the rebel forces showed no one individual could be singled out simply for responsibility for the rebellion.[citation needed]

After the Thái Nguyên uprising, Vietnamese anti-colonialism acquired a new dimension. Marr characterised the period between 1925–1945 as one where two streams of anti-colonialism ('anti-imperial' and 'anti-feudal') had merged plus the evolution of national consciousness spreading not only amongst the elites but also the peasantry and villagers.[42] Education had affected more people, more Vietnamese students were educated overseas, and Vietnamese nationalism became political and "urban". An array of 'modern' movements began to emerge during the 1920s and 1930s. The middle class in Vietnam assumed a bigger role in political initiative and nationalist political parties such as Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng (VNQDĐ) and communist parties like the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) and others began to emerge and establish themselves in Vietnamese politics and history. They were more successful than their predecessors in integrating anti-colonial forces from different parts of French Indochina and establishing organisation structures and communication channels that transcended class divisions and geographical boundaries. Subsequent battles against the French during World War II and the Battle of Dien Bien Phu showed the French Army was not invincible.[citation needed]

The colonial prison system – fostering nationalism against French colonial rule

editApart from the sense of transition from 'traditional' to 'modern' Vietnamese nation-consciousness in the movements after the 1920s, Zinoman argues that "prisons were as significant as schools and political parties in creating a 'consciousness of connectedness'", and the Thái Nguyên uprising may be considered as amongst the "earliest manifestations of modern anti-colonial nationalism".[43] The colonial penal institution, "founded to quell political dissent and maintain law and order" was in turn appropriated by the imprisoned into "a site that nurtured the growth of communism, nationalism, and anti-colonial resistance".[44] He argued that the same prison system helped strengthen common identities and the growth in dissemination of anti-colonial ideology when prisoners were circulated amongst different prisons in Vietnam (including at Poulo Condore). Specifically, the ICP used the prison as a centre of communist cadre recruitment and ideology indoctrination as the prison context grouped diverse categories of prisoners together and fostered amongst them strong bonds, common identities and political direction. This same situation was already witnessed earlier in the Thái Nguyên uprising, where the prisoners and the prison guards shared similar conditions of being maltreated by the French and forged common identities of anti-colonialism which was the unifying basis for their decision to rebel.[citation needed]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Drawing from sources such as colonial records, newspapers and prisoner memoirs, Peter Zinoman's book on the colonial prison system in Vietnam titled "The Colonial Bastille: A History of Imprisonment in Vietnam, 1862–1940" included a chapter on the Thái Nguyên uprising of 1917 which would be considered the most comprehensive account of the event written in English by far. There is a separate reference for the chapter – Zinoman, Peter (2000). "Colonial Prisons and Anti-colonial Resistance in French Indochina: The Thái Nguyên Rebellion, 1917". Modern Asian Studies 34: 57–98. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00003590

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 57.

- ^ Lâm, Truong Buu. A Story of Việtnam. Denver, CO: Outskirts Press, 2010.

- ^ Hodgkin, Thomas. Vietnam: The Revolutionary Path. London: Macmillan, 1980, p. 213.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 57.

- ^ Marr, D. G. (1971). Vietnamese anticolonialism, 1885–1925. Berkeley, University of California [Press], p. 236. See also Hodgkin, p. 214.

- ^ Hodgkin, p. 214.

- ^ Marr, p. 53.

- ^ Marr, p. 275.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 58.

- ^ Marr, p. 234.

- ^ Marr, p. 234.

- ^ This was despite the alternative strategy presented by the lieutenants of Hoàng Hoa Thám (Đề Thám), who was a deceased leader of an outlaw band that was anti-French and provided support to urban anti-colonial activist Phan Boi Chau. Đề Thám favoured abandoning the town and launching attacks on nearby French outposts. Quyến was expecting reinforcements from Đề Thám's band and the Viet Nam Restoration League to arrive later and buttress the insurgency. See Zinoman (2000), p. 79 and Marr, p. 235.

- ^ These locations included the courthouse, treasury and post-office.

- ^ The English translation of the proclamation can be found in Lâm, Truong Buu. Colonialism Experienced: Vietnamese Writings on Colonialism, 1900–1931. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan, 2000.

- ^ The guards formed one battalion while the second group of political prisoners and civilians was led by Ba Chi, a lieutenant previously under Đề Thám.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), pp. 66–67.

- ^ Marr, p. 236.

- ^ A confirmed opium addict and heavy gambler, Cấn was rumoured to be illiterate. Zinoman (2000), p. 64.

- ^ Tran Huy Lieu (1901–1969) was the Democratic Republic of Vietnam's preeminent historian during the 1950s and 1960s. Lieu was a writer, revolutionary activist, historian and journalist in Vietnam. He held various senior leadership positions (such as the Minister of Communications and Information) in the first government of North Vietnam. See vi:Trần Huy Liệu

- ^ Marr, pp. 234–236.

- ^ Marr, pp. 216–221.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 83.

- ^ Phan had praised Quyến in his memoirs as the 'most admirable' of all Vietnamese students in Japan. See Zinoman (2000), pp. 61–63.

- ^ Lâm, Truong Buu. Colonialism Experienced: Vietnamese Writings on Colonialism, 1900–1931. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan, 2000.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 83.

- ^ Political disorder in China added to the lawlessness in the middle region given the porous borders.

- ^ Hodgkin, p. 213.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 78.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 81.

- ^ Zinoman, Peter. (2001). The colonial Bastille: a history of imprisonment in Vietnam, 1862–1940. Berkeley, University of California Press.

- ^ Even with the introduction of Article 91 of the Indochinese criminal code in the 1890s that sought to differentiate political offences with other crimes, prisoners were still subjected to a common regime.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 90.

- ^ Zinoman also studied the rise in numbers and case studies of prison revolts (such as Poulo Condore 1918 and Lai Chau 1927) and attributed such phenomena to distrust of the colonial legal and juridical system, harsh and erratic local administrative systems, organization of prison labour, and attacks on prisons led from outside forces (secret societies, peasants).

- ^ Darles was portrayed pejoratively in both colonial records and Vietnamese accounts. See Zinoman (2000), pp. 91–95.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), pp. 67–74.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 68.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 88.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 74.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), pp. 95–96.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 58.

- ^ Marr, p. 276.

- ^ Zinoman (2000), p. 98.

- ^ Zinoman, The Colonial Bastille: A History of Imprisonment in Vietnam, 1862–1940, p. 4.

References

edit- Zinoman, Peter (2000). "Colonial Prisons and Anti-colonial Resistance in French Indochina: The Thai Nguyen Rebellion, 1917". Modern Asian Studies 34: 57–98. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00003590

- Zinoman, Peter (2001). The colonial Bastille: a history of imprisonment in Vietnam, 1862–1940. Berkeley, University of California Press.

- Lâm, Truong Buu. A Story of Việtnam. Denver, CO: Outskirts Press, 2010.

- Hodgkin, Thomas. Vietnam: The Revolutionary Path. London: Macmillan, 1980.

- Marr, D. G. (1971). Vietnamese anticolonialism, 1885–1925. Berkeley, University of California [Press].

- Lâm, Truong Buu. Colonialism Experienced: Vietnamese Writings on Colonialism, 1900–1931. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan, 2000.

- Lam, T. B. and M. Lam (1984). Resistance, rebellion, revolution: popular movements in Vietnamese history. Singapore, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.