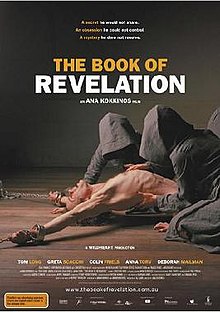

The Book of Revelation is a 2006 Australian arthouse film directed by Ana Kokkinos and starring Tom Long, Greta Scacchi, Colin Friels, and Anna Torv. The film is adapted from the 2000 psychological fiction novel by Rupert Thomson. It tells the story of vengeance of a dancer named Daniel who is abducted and raped. It was produced by Al Clark and the soundtrack was created by Cezary Skubiszewski.

| The Book of Revelation | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Ana Kokkinos |

| Written by | Rupert Thomson (novel) Ana Kokkinos Andrew Bovell |

| Produced by | Al Clark |

| Starring | Tom Long Greta Scacchi Colin Friels Anna Torv |

| Cinematography | Tristan Milani |

| Edited by | Martin Connor |

| Music by | Cezary Skubiszewski |

Release date |

|

Running time | 119 minutes |

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Box office | A$271,261 (Australia)[1] |

Plot

editDaniel (Tom Long), an Australian classical dancer, is drugged and abducted in an alley by three hooded women. They proceed to hold him in an abandoned warehouse for about two weeks, mutilating him sexually and using him for their own physical and psychological gratification, before dumping him blindfolded from a car near his home.[2]

Traumatised, Daniel neither reports his kidnapping and rape to the authorities, nor reveals it to family, friends or colleagues. In the aftermath, he loses his ability to dance and has problems readjusting to normal life. His sceptical live-in lover, a ballerina, suspecting that he was unfaithful to her during his absence, leaves him. Obsessed with finding the culprits, who he has reason to believe are from the vicinity, he dates every woman who bears a resemblance to his abductors, hoping to identify them. This leads him into trouble with the law, and to an eventual breakdown that may or may not prove cathartic. The film concludes on this ambiguous note, with Daniel weeping in the arms of a policeman.[2]

Cast

edit- Tom Long as Daniel

- Greta Scacchi as Isabel

- Colin Friels as Olsen

- Anna Torv as Bridget / Leading Hooded Woman

- Deborah Mailman as Julie

- Nadine Garner as Margot

- Zoe Coyle as Renate

- Zoe Naylor as Astrid

- Odette Joannidis as Maude

- Nina Liu as Vivian

- Sibylla Budd as Deborah

- Geneviève Picot as Barmaid

Production

editThe initial shoot took place over seven weeks during March and April 2005. However, the initially planned final week of shooting was delayed four months due to lead actor, Tom Long, breaking his ankle on set.[2] Kokkinos subverts the original Amsterdam setting of the novel and replaces it with the inner-city streets of Melbourne. The production used forty-two locations, often switching between gentrified Melbourne and more sterile urban scapes.[2] The change between the two settings is timed with Daniel's abduction and rape, and is purposefully crafted by Kokkinos to represent his internal trauma.[3] In conjunction with the shifting city-scape, Kokkinos elected to employ blackouts as transition shots to emphasise Daniel's emotional isolation that proceeds his rape.[4]

As dance is featured heavily in the film, the successful casting of Tom Long as Daniel was reliant on his dancing abilities rather than solely his skill as an actor. Similarly, Greta Scacchi clinched her role as Isabel based on her strong dancing ability as she had grown up dancing with her mother who was a professional. Regardless, Kokkinos had been a long time admirer of her performances in other roles.[2] Colin Friels, who plays Olsen, was drawn to the script due to Kokkinos' reputation for being meticulous in her preparation and emphasis on rehearsing for perfection.[2] In contrast to the depiction of Julie in the novel, Kokkinos subverts her identity for an Australian context and casts Deborah Mailman who is an Indigenous Australian.[2] Bridget, who is played by Anna Torv, was cast as a foil character to Julie, who is self-absorbed in dance, yet fails to extend that passion into other areas of her life.[2] Kokkinos notes that her biggest challenge for the casting of the female leads was that their identity remains anonymous yet the audience is expected to engage with them like the lead Daniel.[2]

Kokkinos invited Australian choreographer, Meryl Tankard, to work on the dance choreography of the film. To enable Kokkinos' desire for dancing to be a key focus of the film, Tankard brought dancers who she already had previously worked with. Initially, she was concerned with the casting of Daniel and Bridget, raising anxieties that they would not pass as credible dancers. However, after Tom Long and Anna Torv spent three months training with Tankard, her fears were alleviated. Tankards' involvement also influenced Greta Scacchi who enhanced her dancing performance in the film by sitting in on many dance rehearsals.[2]

Themes and interpretations

editThe film has been the subject of discussion and interpretation from numerous critics as it explores a gendered perspective of rape and sexuality.

Rape-revenge

editOne interpretation of the film is that it re-imagines the rape-revenge genre. It is argued that this is achieved through the gendered reversal of a male rapist with a female. Academics, Kelly McWilliam and Sharon Bickle note that this type of film follows a three part structure which firstly features the rape of the protagonist, followed by their recovery where they take on the role of the avenger, and then the third phase where they pursue the act of revenge.[5] In the case of The Book of Revelation, it has been suggested that during the second and third phase Daniel fails to transform and remains destabilised.[5] Much of the rape trauma is depicted in the form of flashbacks, as Daniel's captivity is revealed through a sequence of physical assaults and sexual abuse. Mcwilliam and Bickle argue that the gendered norms are emphasised to the audience during Daniels forced masturbation scene as he "reasserts his subjectivity by telling the women 'when a man fucks a woman, no matter how beautiful she is, whenever he closes his eyes he always thinks of himself'. This briefly reinstates the male as active (the one who 'fucks') and beauty as a passive quality possessed by women".[5] The continued destabilisation renders Daniel to be transformed into an outsider as he remains vulnerable and fails to adapt to his new set of circumstances.[6] In alignment with the rape-revenge genre, Daniel is reduced from an active physical state to passive one after he is sodomized. McWilliam argues that this physical change is associated with the female body becoming a passive object.[6] In Daniel's case, his search for vengeance is disorderly, and he is no longer a functioning member of society. As Mcwilliam and Bickle argue "rather than offering revenge as a counter-narrative to rape trauma, the film sets up revenge as a site of further trauma, an expansion of the initial crime. In terms of the rape-revenge genre, Kokkinos' text denies the role of revenge as a form of return or reinstatement of the status quo: instead, the outcome of rape is a rolling state of trauma".[5] Academic Claire Henry similarly argues that Kokkinos successfully re-imagines the genre from the perspective of sensitivity. This is the case due to the male rape victim and an emphasis on Daniel's traumatic life post-rape.[7]

Bodies as objects

editA number of academics cite the significance of Kokkinos' minimal use of dialogue whereby attention is directed to the physicality of the characters' bodies. Kelly McWilliam and Sharon Bickle point out that language in the film is representative of Daniel's uncertain relationship with the other female characters, including his attackers.[5] This interpretation of the film becomes apparent when Daniel is sodomised and reduced to a passive participant in his own rape and post-rape world. In contrast, academic Janice Loreck points out that this transformational scene feels anti-voyeuristic rather than objectifying the male body. Instead, she suggests that Daniel's delirium and attempted objectification are confronting, but falls short of objectifying the male body.[8] Loreck therefore proposes that such confrontation forces the viewer "into a reflexive awareness of his or her act of looking, disrupting any sense of voyeuristic surreptitiousness and imaginary unity".[8] Daniel's post-rape trauma has also been interpreted by Mcwilliam and Bickle who apply Sara Ahmed's Queer Phenomenology. The duo suggest that the rape trauma and objectification of the male body is an issue of spatial orientation. In their article 'Re-imagining the rape-revenge genre: Ana Kokkinos 'The Book of Revelation', the pair adopt Ahmed's view that bodies "become orientated by how they take up time and space' and 'orientations towards sexual objects affect other things that we do such that different orientations, different ways of directing one’s desires, means inhabiting different worlds".[5] Mcwilliam and Bickle argue that through this lens, Kokkinos re-defines the rape-revenge genre through her departure from the normative female victim, as when Daniel is sodomised they note "the shift in orientation from vertical to horizontal can be interrupted as Daniel’s transformation from subject to object".[5]

Biblical references

editThe most widely acknowledged Biblical allusion is in the film's title, which is a reference to the Book of Revelation in the New Testament. As this section of the New Testament depicts the second coming of Christ and describes an armageddon-like vision of death, it has been suggested that Daniel's struggle to maintain control over his body, and the power of rape to bring about devastation, echoes the apocalyptic nature of the biblical chapter.[5]

Reception

editCriticism

editThe film has been the subject of criticism from numerous academics and film critics. Academic Claire Henry posits that the film could have enjoyed more success had it been clearly represented as an erotic thriller rather than an examination of rape suffering.[7] Notable film critic Mark Fisher in a review of the film published in Sight & Sound views the film as being "hyperbolic absurdity".[9] He additionally contends that the controlling logic of the film is distorted and therefore undermines its rape-revenge genre tag. For instance, it's unclear whether it's the male fantasy of being humiliated or the female fantasy to degrade a man.[9] In another review by Fincina Hopgood the film is criticised as there is a lack of connection between character and audience. She argues that the audience has insufficient time to build rapport with Daniel prior to him being raped. Instead, the focus on the female characters makes it difficult to empathise with Daniel as the focus is thrust upon him. Furthermore, she claims that Daniels' inability to articulate his feelings means the audience is reliant on his body language to express his emotional status and therefore deducts from the overall message of the film.[10] Russell Edwards claims that the film struggled to deal with the topic of rape in an intellectual and emotional manner. He accordingly places blame on lead actor, Tom Long, claiming he is "A limited actor whose lethargic presence serves the post abduction scenes well, Long lacks the vitality in the opening reels to provide a basis for a character arc". He however notes, the soundtrack composed by Cezary Biszewski in conjunction with Meryl Tankard's choreography contributes to the authenticity of the setting and poignant atmosphere.[11]

Film critic Megan Lehmann similarly posits the scene that contains sodomy fails to capture the subject of rape-revenge in an authentic manner and is more reflective of soft-core porn. This in turn, reduces the effectiveness of the emotional convulsions during the flashback scenes. She further criticises Kokkinos' reliance on the gender role reversal and the subplot of Scacchi's character, claiming that the film would have been improved had it focused on the aftermath of the trauma.[12]

Australian film reviewer, Paul Byrnes assessed the film in a positive light, pointing to Kokkinos' willingness to explore a controversial subject and depict rape-revenge in a more confrontational manner than prior Australian directors. Byrnes argues that the film is driven more by ideas than shock value, whereby the reversal of the gendered norms concerning rape allowed Kokkinos to reinvigorate the genre in a way that allows the audience to experience the emotions of the characters and empathise the trauma of a rape victim.[4]

Awards

editThe film was nominated for Best Screenplay - Adapted, Best Original Music Score and Best Costume Design awards at the Australian Film Institute in 2006. It won the Best Music Score (Cezary Skubiszewski) at the Film Critics Circle of Australia Awards, where it was nominated for four more awards.[13]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Film Victoria. (2006). Australian Films at the Australian Box Office [Image]. Film Victoria, Victoria. Retrieved http://www.film.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/967/AA4_Aust_Box_office_report.pdf Archived 9 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j O'Neill, S. (2006). The Book of Revelation. Retrieved from The Book of Revelation website: http://static.thecia.com.au/reviews/b/book-of-revelation-production-notes.rtf

- ^ French, L. (2013). Ana Kokkinos. Retrieved from Senses of Cinema website: https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2013/contemporary-australian-filmmakers/ana-kokkinos/

- ^ a b Byrnes, P. (2006). The Book of Revelation. Retrieved from Australian Screen website: https://aso.gov.au/titles/features/the-book-of-revelation/notes/

- ^ a b c d e f g h McWilliam, Kelly; Bickle, Sharon (3 September 2017). "Re-imagining the rape-revenge genre: Ana Kokkinos' The Book of Revelation". Continuum. 31 (5): 706–713. doi:10.1080/10304312.2017.1315928. S2CID 152078372.

- ^ a b McWilliam, K. (2019). The Book of Revelation: Othering the Centre. In L. Bolton & R. Rushton (Eds.), Ana Kokkinos: An Oeuvre of Outsiders (pp. 76-82). Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press

- ^ a b Henry, C. (2014). The Book of Revelation. In R. Curtis & E. Buchman (Eds.), Revisionist rape-revenge: redefining a film genre (pp. 125-128). New York, United States: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ a b Loreck, Janice Peta (16 February 2017). Difficult subjects: women, violence and subjectivity in distinguished cinema (Thesis). doi:10.4225/03/58a51687457fb.

- ^ a b Fisher, Mark (April 2008). "The Book of Revelation". Sight and Sound. 18 (4). British Film Institute: 46–47. ProQuest 237120956.

- ^ Hopgood, Fincina (2006). "'The Book of Revelation': Showing without Telling". Metro Magazine: Media & Education Magazine (150): 32–36.

- ^ Edwards, Russell. "The Book of Revelation". Variety. 403 (11). Los Angeles: 22. ProQuest 1958972.

- ^ (Lehmann, M. (2006). "The Book of Revelation".(Movie review) [Review of "The Book of Revelation".(Movie review)]. Hollywood Reporter, 395(24). The Nielsen Company.)

- ^ The Book of Revelation (2006) at IMDb