'The Holy Tulzie', 'The Twa Herds' or 'An Unco Mournfu' Tale was a poem written in 1784 by Robert Burns whilst living at Mossgiel, Mauchline, about a strong disagreement, not on doctrine, but on the parish boundaries, between two 'Auld Licht' ministers, John Russel and Alexander Moodie[1] It was followed by "The Holy Fair", "The Ordination", "The Kirk's Alarm", "Holy Willie's Prayer", etc.

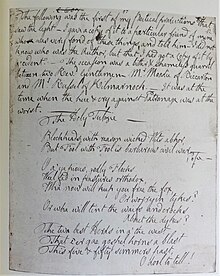

Burns holograph of The Holy Tulzie or The Twa Herds | |

| Author | Robert Burns |

|---|---|

| Original title | The Holy Tulzie |

| Language | Scots |

| Genre | Poems |

| Publication place | Scotland |

History

editThe poem was first published in 1796 by Stewart and Meikle, Glasgow in one penny or two penny pamphlet 'Chap-book' form, 18 mo size.[2] Tulzie in Scots means 'a brawl'.[3] Because of its controversial content it didn't appear in any edition of Burns's Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect during his lifetime.[3] It appeared as a pamphlet again in 1799 on Saturday, 3 August[4] and in book form in 1801.[5]

Lockhart comments that this was "a piece not given either by Currie or Gilbert Burns, though printed by Mr. Paul, and omitted, certainly for no very intelligible reason, in editions where "The Holy Fair", "The Ordination," found admittance.[6]

The Reverends Moodie and Russel

editBoth ministers were elected by their congregations, unlike the Rev James Mackinlay whose patron at the Laigh Kirk was the Earl of Glencairn and the resulting dissatisfaction led to Burns penning "The Ordination".[7] Both were Auld Licht Calvinists.[8]

- Alexander Moodie (1728-1799)

Moodie was the minister of Riccarton Church near Kilmarnock, having been educated at Glasgow University and starting his ministry at Culross in 1759.[9] He was buried in the Riccarton churchyard, but the present church wasn't built until 1823.[10]

Alexander was a Calvinist and a dedicated adherent of the Auld Licht views. He had a hyperactive and deafening preaching style.[11] Burns also references him in the Holy Fair[11] with :

|

This was followed by a lampooning in The Kirk's Alarm where his swarthy complexion earned him the title of Singet Sawnie.[11]

- John Russel (1740-1817)

Originally from Moray, Black Jock taught at the Cromarty parish school and upon being ordained he became, in 1774, the minister of the High Church in Kilmarnock.[12][13] At his Cromarty school he was remembered by Hugh Miller in his "Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland" as a "large, robust, dark-complexioned man, imperturbably grave, and with a sullen expression seated in the deep folds of his forehead".[14] He was "more ready to thunder forth the terrors of the law than to woo the wicked from the error of their ways, by setting before them the Saviour's love, so fully and freely manifested in the soothing and soul-captivating strains of the gospel". The nickname 'Black Jock or Joke' is a punning reference to the female genitalia.[15]

On Sabbaths between Divine service, Russell patrolled the streets of Kilmarnock and even ventured into the countryside, walking stick in hand, on the look out for children or adults actively enjoying themselves. "Such as he discovered, he would visit on the following morning, and severely rebuke for their ungodliness."[16] He set the parish in such terror that doors would close and faces would take on a serious contenance should the sound of his walking stick be heard.

Like his colleague at Riccarton he was an Auld Licht Calvinist with the same hellfire and damnation bellicose preaching style.[14] He appears in the "Holy Fair" he figures as Black Russell and as Wordy Russell in "The Twa Herds".[14] In the "Kirks Alarm" Burns highlights his Auld Licht style :

|

He was well versed in religious knowledge and on one occasion he met Burns in a barber's in Fore Street where they became embroiled in a heated discussion on a point of religious topic, that after a while had Burns overwhelmed and he silently accepted defeat by hurriedly leaving the premises.[17]

Russel was an author with several religious pamphlets and books to his credit.[14] He moved to Stirling and was buried there in the churchyard of the Church of the Holy Rood where the memorial intimates that he was well respected by the time of his death.[10]

The High Church in Kilmarnock was greatly altered in 1868 with stained glass, an organ provided and other improvements made. Burns's first printer, John Wilson, was buried in the kirkyard. The building is no longer in use as a church however the kirkyard can still be accessed.[18]

The parish boundaries dispute

editThe two ministers had been friends however a dispute over the boundaries of their respectives parishes developed into a furious argument and public scandal that attracted Robert Burns's poetic talents with impressive results. This dispute had come before the Presbytery at Irvine for resolution with many people present from the parishes in question, however "the two protagonists tore at each other like strutting cockerels, showing little Christian forbearance."[3] Burns referred to the dispute as a "bitter and shameless quarrel ..., at the time when the hue and cry against patronage was as the worst."[5] Lockhart's description was that the pair fell foul of each other "with a fiery virulence of personal invective, such as has been banished from all popular assemblies, wherein the laws of courtesy are enforced by those of a certain unwritten code.."[19]

The story told locally may go some way towards explaining the heated exchanges for it is said that the pair were riding home from Ayr one evening when Moodie, being in a cheerful mood, "tickled the rear of his neighbour's horse with his switch, causing it to perform certain antics which sadly discommoded "Rumble John", and made him the amusement of passing wayfarers."[19]

Robert Burns letter to Dr. Moore

editBurns's autobiographical letter to John Moore written at Mauchline on 2 August 1787 gives us some insight into the origin of the poem:

"I now began to be known in the neighborhood as a maker of rhymes. The first of my poetic offspring that saw the light was a burlesque lamentation on a quarrel between two reverend Calvinists, both of them dramatis personae in my Holy Fair. I had an idea myself that the piece had some merit; but to prevent the worst, I gave a copy of it to a friend who was very fond of these things, and told him I could not guess who was the Author of it, but that I thought it pretty clever. With a certain side of both clergy and laity it met with a roar of applause. Holy Willie's Prayer next made its appearance, and alarmed the kirk-Session so much that they held three several meetings to look over their holy artillery, if any of it was pointed against profane Rhymers".[20]

Burns's comment "The first of my poetic offspring that saw the light" has often been misunderstood as meaning that this 1784 poem was his first poetic work, but it is only a reference, with a pun on the word light as in Auld licht, meaning that this was the first of his unprinted, but widely copied and circulated poems to catch the awareness of the general public, so that he was recognised as a poet for the first time. As stated, it was first printed in 1796 after his death under the title "An Unco Mournfu' Tale".[21]

The Twa Herds

edit

|

|

Ministers mentioned in the 'Twa Herds'

edit1: Rev. Mr. Moodie of Riccarton[9]

2: Rev. John Russel of Kilmarnock[12][13]

3: Dr. Robert Duncan of Dundonald[22]

4: Rev. William Peebles of Newton-on-Ayr[23]

5: Rev. William Auld of Mauchline[24]

6: Rev. Dr. William Dalrymple of Ayr[25]

7: Rev. William M'Gill, colleague of Dr. Dalrymple[26]

8: Rev. Dr. William M'Quhae, Minister of St. Quivox[27]

9: Dr. Andrew Shaw of Craigie,[28] and Dr. David Shaw of Coylton[29]

10: Patrick Wodrow of Tarbolton[30] (son of Robert Wodrow, the historian of the Covenanters.)

11: Rev. John M'Math, a young assistant and successor to Wodrow[31]

12: Rev. George Smith of Galston[32]

Notes on 'The Twa Herds'

editMost of these individuals were 'Auld Licht' however the University of Glasgow-educated William Dalrymple and Robert Duncan were 'New Licht', the more liberal minded ministers, as were McGill, Patrick Wodrow, William McQuhae, David and Andrew Shaw and McMath.[33] The 'New Lichts' were are referred to as 'Arminian', meaning that they had a moderate liberal theology as developed by Jacobus Arminius, were moralistic in their preaching and served their flock with understanding and compassion.

The right of the patronage held by landowners to choose the minister, rather than the congregation, is a theme here as it was very contentious at the time and Burns even suggests that congregations should seek the right to choose their minister. The plaid reference is to the dress worn at the time as 'shepherds' to their flock or 'herd'. Burns used the term 'Brutes' to describe the ministers congregations however this can be seen in the light of the Russel and Moodie being shepherds of their respective herds, as in "The Twa Herds".[21]

Aftermath

editThe climax of the poems on a religious theme such as "Address to the Deil", "The Kirk's Alarm", "The Ordination" and "The Holy Fair" was "Holy Willie's Prayer."[5] Written in 1785 and first printed anonymously in an eight-page pamphlet in 1789.[34] It is considered the greatest of all Burns' satirical poems, amongst the finest satires ever written,[35] a withering attack on religious hypocrisy. Burns wrote to Cunningham: “If there be any truth in the orthodox faith of the Churches, I am damned past redemption, and, what is worse, damned to all eternity.”[36]

See also

edit- Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (Edinburgh Edition)

- Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (Second Edinburgh Edition)

- Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (London Edition)

- Robert Burns's Commonplace Book 1783–1785

- Robert Burns's Interleaved Scots Musical Museum

- Robert Burns World Federation

- Glenriddell Manuscripts

- Burns Clubs

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Noble, Andrew (2001). The Canongate Burns. Canongate Classics. p. 554, Vol. 2.

- ^ Noble, Andrew (2001). The Canongate Burns. Canongate Classics. p. 552, Vol. 2.

- ^ a b c Hogg, Patrick Scott (2008). Robert Burns The Patriot Bard. Mainstream Publishers. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-84596-412-2.

- ^ Burns 1890, p. 82.

- ^ a b c Noble, Andrew (2001). The Canongate Burns. Canongate Classics. p. 555, Vol. 2.

- ^ Lockhart 1828, 63.

- ^ Leask, Nigel (2010). Robert Burns and Pastoral. Oxford University Press. p. 201.

- ^ Smith 2006.

- ^ a b Scott 1920, 64.

- ^ a b McQueen, Colin Hunter (2009). Hunter's Illustrated History of the Family, Friends, and Contemporaries of Robert Burns. Hunter McQueen & Hunter. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-9559732-0-8.

- ^ a b c Purdie, David (2013). Maurice Lindsay's The Burns Encyclopaedia. Robert Hale. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-7090-9194-3.

- ^ a b Scott 1920, 109.

- ^ a b Scott 1923, 326.

- ^ a b c d e Purdie, David (2013). Maurice Lindsay's The Burns Encyclopaedia. Robert Hale. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-7090-9194-3.

- ^ Leask, Nigel (2013). The Oxford Edition of the Works of Robert Burns. Vol I. Commonplace Books, Tour Journals and Miscellaneous Prose. Oxford University Press. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-19-960317-6.

- ^ M'Kay 1880, p. 117.

- ^ M'Kay 1880, p. 118.

- ^ M'Kay 1880, p. 120.

- ^ a b Burns 1890, p. 190.

- ^ "Robert Burns World Federation". Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ a b Leask, Nigel (2010). Robert Burns and Pastoral. Oxford University Press. p. 186.

- ^ Scott 1920, 36.

- ^ Scott 1920, 13-14.

- ^ Scott 1920, 50.

- ^ Scott 1920, 10.

- ^ Scott 1920, 12-13.

- ^ Scott 1920, 66-67.

- ^ Scott 1920, 23.

- ^ Scott 1920, 21.

- ^ Scott 1920, 75-76.

- ^ Scott 1920, 76.

- ^ Scott 1920, 40.

- ^ Leask, Nigel (2010). Robert Burns and Pastoral. Oxford University Press. p. 187.

- ^ Daiches, David (1952). Robert Burns. London: G. Bells

- ^ "Fisher, William (1737–1809)". The Burns Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-06-16.

- ^ Muir 1932, p181.

Sources

edit- Burns, Robert (1890). Douglas, William Scott (ed.). The Kilmarnock edition of the poetical works of Robert Burns, arranged in chronologial order with new annotations, biographical notices, etc (7 ed.). Kilmarnock: D Brown & Co.

- Lockhart, John Gibson (1828). The Life of Robert Burns. Edinburgh: printed for Constable and Co.

- M'Kay, Archibald (1880). The History of Kilmarnock (4 ed.). Archibald M'Kay.

- Muir, James (1932). The religion of Robert Burns. Scottish Church History Society. pp. 176-183.

- Moody, Alexander (1791). "Parish of Riccartoun". The statistical account of Scotland. Vol. 6. Edinburgh: W. Creech. pp. 117-120.

- Scott, Hew (1917). Fasti ecclesiæ scoticanæ; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

- Scott, Hew (1920). Fasti ecclesiæ scoticanæ; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. Vol. 3. Edinburgh : Oliver and Boyd.

- Scott, Hew (1923). Fasti ecclesiæ scoticanæ; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. Vol. 4. Edinburgh : Oliver and Boyd.

- Smith, Richard M. (2006). "Auld Licht, New Licht and Original Secessionists in Scotland and Ulster". Scottish Church History Society: 97–124.

Further reading

edit- Brown, Hilton (1949). There was a Lad. London : Hamish Hamilton

- Douglas, William Scott (Edit.) 1938. The Kilmarnock Edition of the Poetical Works of Robert Burns. Glasgow : The Scottish Daily Express.

- Hecht, Hans (1936). Robert Burns. The Man and His Work. London : William Hodge

- Mackay, James (2004). Burns. A Biography of Robert Burns. Darvel : Alloway Publishing. ISBN 0907526-85-3.

- McIntyre, Ian (2001). Robert Burns. A Life. New York : Welcome Rain Publishers. ISBN 1-56649-205-X.

- McQueen, Colin Hunter (2008). Hunter's Illustrated History of the Family, Friends and Contemporaries of Robert Burns. Messsrs Hunter McQueen & Hunter. ISBN 978-0-9559732-0-8

- Pittock, Murray (2018). The Oxford Edition of the Works of Robert Burns. Volumes II and III: The Scots Musical Museum.ISBN 9780199683895.

- Purdie, David, McCue & Carruthers, G (2013). Maurice Lindsay's The Burns Encyclopaedia. London : Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-9194-3

External links

edit- Researching the Life and Times of Robert Burns Club Researcher's site.