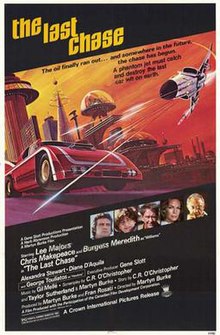

The Last Chase is a 1981 Canadian-American dystopian science fiction film directed by Martyn Burke who was also the producer on the film, produced for Argosy Films. The film stars Lee Majors, Chris Makepeace and Burgess Meredith in a futuristic scenario about a former racing driver who reassembles his old Porsche car and drives to California in a world where cars and motor vehicles of all kinds have been outlawed by the authorities.[2]

| The Last Chase | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Martyn Burke |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | C.R. O'Christopher |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Music by | Gil Melle |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Crown International Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 101 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

Plot

editIn the year 2011, the United States is a police state. A substantial percentage of the population was wiped out by a devastating viral pandemic 20 years earlier. Amidst the resulting chaos and general panic, democracy collapsed and a totalitarian cabal seized power. After moving the seat of government to Boston, the new dictatorship outlawed private ownership and use of all automobiles, boats and aircraft, on the pretext that an even bigger crisis, the depletion of fossil fuel supplies, was imminent. The loss of other personal freedoms followed, and a mass surveillance system now monitors private citizens' every move.

In Boston, Franklyn Hart, a former race car driver who lost his family to the plague, is a spokesman for the mass transit system. Publicly, he deplores the selfishness of private vehicle ownership and exalts the virtues of public transportation; privately, he is barely able to contain his contempt for the oppressive, autocratic bureaucracy and the dismal party line that he is compelled to promote.

Years before, as private vehicles were being confiscated, Hart sequestered his race car – an orange Porsche 917 CAN-AM roadster – in a secret compartment beneath his basement. Over the ensuing years he has gradually restored it to drivable condition, raiding long-abandoned junkyards in the dead of night for parts. His goal is to drive across the country to "Free California", an independent territory that has seceded from the rest of totalitarian America. Young electronics whiz Ring McCarthy deduces Hart's plan, and Hart reluctantly agrees to bring him along on his perilous journey.

The ubiquitous surveillance system catches Hart vaulting a junkyard fence; Hart and McCarthy flee Boston in the roadster as police close in. Although gasoline has not been sold for 20 years, Hart has access to a virtually inexhaustible supply, the residual fuel remaining at the bottom of subterranean storage tanks in every abandoned gas station in the country. He uses a portable hand pump to refuel from these tanks as necessary.

News of the duo's daring adventure spreads across the country. The government, represented by a Gestapo-like figure named Hawkins, watches with growing concern as the public takes notice and cheers Hart's defiance of authority. Calls for a return to personal autonomy and democracy are heard, for the first time in two decades. Hart must be stopped; but ground pursuit is impossible, as the electric golf carts used by the police are incapable of chasing down a race car.

Hawkins orders J. G. Williams, a retired Air Force pilot, to track down and destroy Hart and his car in a Korean War-vintage F-86 Sabre. He locates and strafes the car, wounding Hart. A community of armed (mostly Native American) rebels takes Hart and McCarthy in, hides the car, and treats Hart's wounds. A team of mercenaries soon locates and attacks the enclave, although Hart and McCarthy escape during the firefight.

Back on the open road, Williams once again has the roadster in his crosshairs; but now he is having second thoughts. As an old rebel himself, he is starting to identify with Hart's situation. Prodded by Hawkins, Williams initiates several more confrontations, but each time he backs off, to Hart's and McCarthy's bewilderment. McCarthy rigs a radio receiver and listens in on Williams's cockpit radio communications, then establishes a dialog with him using Morse code via a hand-held spotlight. Eventually Williams confides that he is sympathetic to their cause.

But Hawkins is also monitoring Williams's radio communications, and after learning of his change of heart, orders the activation of a Cold War-era laser cannon at a position ahead of Hart's route. Williams attempts to warn Hart, but his radio communications have been jammed. Williams releases his external fuel tanks ahead of the car, hoping the inferno will stop the car short of the cannon's range; but Hart, assuming Williams has changed allegiances yet again, drives on.

Williams strafes the laser, but cannot pierce its heavy armor; so he sacrifices himself in a kamikaze-style attack, destroying his jet and the laser installation. His sacrifice allows Hart and McCarthy to drive on toward California where they are welcomed as heroes.

Cast

edit- Lee Majors as Franklyn Hart

- Chris Makepeace as Ring McCarthy

- Burgess Meredith as Captain J.G. Williams

- Alexandra Stewart as Eudora

- Diane D'Aquila as Santana

- George Touliatos as Hawkins

- Harvey Atkin as Jud

- Ben Gordon as Morely

- Hugh Webster as Fetch

- Deborah Burgess as Miss Rawlston

- Trudy Young as Mrs. Hart

- Moses Znaimer as Reporter

- Doug Lennox as Captain

- Paul Amato as Soldier at roadblock

- Warren Van Evera as New York Cop (as Warren Van Evra)

Production

editThe script for The Last Chase was originally written by Christopher Crowe back in the 1970s, the rights for the script were bought by a studio for $50,000, Crowe would later have his name taken off the film, and he was credited under his pseudonym, C.R. O'Christopher.[3]

Principal photography began on October 9, 1979, with production wrapping on December 4, 1979. The film locations included locales in both the United States and Canada. The Last Chase was filmed in Tucson, Flagstaff, Marana, Sedona and Phoenix, Arizona, along with the Sonoran Desert. The film was also shot in Port Credit, Caledon, Toronto and the Mosport International Raceway, Clarington, Durham, Ontario, Canada.[4]

The aircraft used in The Last Chase was a Canadair CL-13 Sabre Mk 6, c/n 1600, N1039C.[5]

Reception

editIn Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide 2013 (2012), film historian and reviewer Leonard Maltin considered The Last Chase to be "a flimsy drama that reeks of Reaganomics".[6]

The review in TV Guide simply stated, "The performances are adequate, but the script fails to balance the car chases with interesting characters".[7]

Home media

editThe Last Chase was originally released on VHS and CED by Vestron Video (now a division of Lions Gate Entertainment). The film was re-released in DVD format in May 2011 via Code Red.[N 1]

References

editNotes

edit- ^ In May 1989, The Last Chase was the subject of episode K20 of the cult KTMA show Mystery Science Theater 3000.[8][9]

Citations

edit- ^ "Review: 'The Last Chase'." American Film Institute, 2019. Retrieved: August 11, 2019.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Review: 'The Last Chase'." AFI, 2019. Retrieved: August 11, 2019.

- ^ Burke, Michael (May 23, 1993). "Horlick alum Christopher Crowe writes place in Hollywood history". Racine Journal Times.

- ^ "Filming and production: 'The Last Chase'." IMDb, 2019. Retrieved: August 11, 2019.

- ^ Santoir, Christian. "Review: 'The Last Chase'." Aeromovies, January 7, 2017. Retrieved: August 11, 2019.

- ^ Maltin 2012, p. 782.

- ^ "Review: 'The Last Chase'." TV Guide, 2019. Retrieved: August 11, 2019.

- ^ "Episode guide: K20- The Last Chase." mst3kinfo.com, 2019. Retrieved: August 11, 2019.

- ^ "The Last Chase (TV episode 1989)." IMDb, 2019. Retrieved: August 11, 2019.

Bibliography

edit- Maltin, Leonard. Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide 2013. New York: New American Library, 2012 (originally published as TV Movies, then Leonard Maltin’s Movie & Video Guide), First edition 1969, published annually since 1988. ISBN 978-0-451-23774-3.