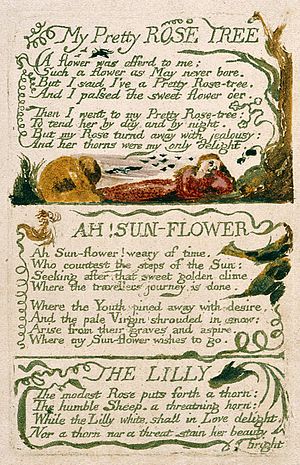

"The Lilly" is a poem written by the English poet William Blake. It was published as part of his collection Songs of Experience in 1794.

Poem

editSummary

editThe Rose, which is a symbol of love and beauty, puts forth a flaw or a thorn. The humble sheep also calls to attention its horn or flaw. The Lilly, however, which is pure and white, enjoys love and has no thorn or flaw to show the world.

Vision of love

editAccording to Antal, Blake's Flower Plate is composed of three flower poems on the same plate for a reason: to illustrate three types of love; Poetic Love, Earthly Love, and Human Love. The Lilly deals with the "Poetic Love" concept of this "threefold vision of love".[3] This is considered the "Poetic Love" because the Lilly is innocent, and pure, and unable to be besmirched by love or by thorns. As Johnson states, "Oddly enough, most emblem designs featuring lilies show the flower surrounded by thorns."[4] Blake's Lilly has no thorns. Unlike the sheep or the Rose, the Lilly is the purest of them all. This echoes poetic love as ideally, love should be flawless. Love should be perfect and everything that people dream of. Even though the two lovers themselves may have flaws, love itself shouldn't have any.

Themes and interpretations

editThough a rather short poem, and for that matter, the shortest poem on the page, "The Lilly" puts forth a great deal of symbolism and figurative language to be interpreted in numerous ways. Though there are many different interpretations out there, the experts seem to agree on two main themes for this poem. The two main themes within this poem are Purity and the Ideal Love.

Purity

editThough Purity is often immediately compared with virginity, some critics argue that The Lilly maintains a rather different kind of purity. Johnson quotes, "The text and design of 'The Lilly' emblematize and celebrate a fresh conception of purity, the purity of gratified desire. To be unstained by thorns is to allow the 'stain' of personal contact, which is the only true whiteness." This purity is not virginity; rather, this purity is knowing what you want and never settling until you get what you desire. You don't alter your desires or ambition despite the circumstances, but keep true to what you truly desire. Instead of allowing the thorns of "personal contact" or attempts at intervention that third parties may have tried to force on her, the Lilly maintains her resolve and stays true to what she knows she desires. Antal captures this idea well when she says "The Lilly, is the most spiritual showing that 'however subject the natural body might be to force and threats, man's spiritual body, like the Lilly, could never be essentially debased'".[3]

Ideal Love

editThe idea of Purity in the poem also trickles into the other theme of Ideal Love. The Ideal Love is often the purest form of love in that the love is pure because it is pure love; there is no game, or flaws to it. The Ideal Love is simply love, purely innocent and true love. Johnson states that "The Lilly who delights in love is another manifestation of the 'sweet flower' offered to the Rose lover in the first poem on his plate." Rather than denying perhaps the true, ideal love, as the man in "My Pretty Rose Tree" does, "The Lilly" vows to delight itself in a pure and true love not besmirched by duty, or any other thorn the rose may bear.

References

edit- ^ Morris Eaves; Robert N. Essick; Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "Songs of Innocence and of Experience, copy F, object 47 (Bentley 43, Erdman 43, Keynes 43) "My Pretty ROSE TREE"". William Blake Archive.

- ^ Blake, William (1988). Erdman, David V. (ed.). The Complete Poetry and Prose (Newly revised ed.). Anchor Books. p. 25. ISBN 0385152132.

- ^ a b Antal [35]

- ^ Johnson [166]

Sources

edit- Antal, Eva. ""Labour of Love"—Ovidian Flower-Figures in William Blake's Songs." Eger Journal of English Studies (2008): 23-40. Web.

- Durant, G. H. "Blake's 'My Pretty Rose Tree'--An Interpretation." Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory (1965): 33–37. Web.

- Durrant, G. H. "Blake's 'My Pretty Rose-Tree'." Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory (1968): 1–5. Web.

- Johnson, Mary Lynn. "Emblem and Symbol in Blake." Huntington Library Quarterly (1974): 151–170. Web.