"The Master Thief" is a Norwegian fairy tale collected by Peter Chr. Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe.[1][2] The Brothers Grimm included a shorter variant as tale 192 in their fairy tales. Andrew Lang included it in The Red Fairy Book. George Webbe Dasent included a translation of the tale in Popular Tales From the Norse.[3]

| The Master Thief | |

|---|---|

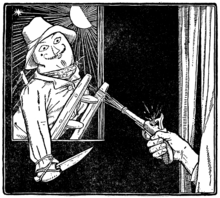

The lord mistakenly shoots the decoy dummy. Illustration from Joseph Jacobs's Europa's Fairy Book (1916) by John D. Batten. | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Master Thief |

| Also known as | Mestertyven; Die Meisterdieb |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | 1525A |

| Country | Norway |

| Published in | |

It is Aarne–Thompson type 1525A, Tasks for a Thief.[4]

Plot

editA poor cottager has nothing to give his three sons, so he walks with them to a crossroad, where each son takes a different road.

The youngest goes into a great woods, and when a storm strikes, he seeks shelter in a house. An old woman nearby warns him that the house is a den of robbers, but he stays anyway. When the robbers arrive, he persuades them to take him on as a servant.

The robbers tell the boy to prove himself by stealing an ox that a man is bringing to market. The boy puts a shoe with a silver buckle in the road. When the man sees it, he thinks it would be good if only he had the other, and he continues on. The boy takes the shoe, runs through the countryside, and puts it in the road again. The man, when he comes across the shoe a second time, leaves his ox to go back and find the other, and the son drives the ox off.

The man goes to get his second ox to sell. The robbers tell the boy that if he steals that one as well, they will take him into the band. The boy hangs himself up along the path, and the man passes him. The boy runs ahead and hangs himself again and then a third time, until the man is half-convinced that it is witchcraft, and when he goes back to see if the first two bodies are still hanging, the son drives off his second ox.

The man gets his third and last ox, and the robbers say that they will make the boy the band's leader if he steals it. The son makes a sound like an ox bellowing in the woods, and the man, thinking it was his stolen oxen, runs off, leaving the third behind, the son steals that one as well.

The robbers are not pleased with the boy leading the band, so they leave him. The boy drives the oxen out so they return to their owner, takes all the treasure in the house, and returns to his father.

The boy wants to marry the daughter of a local squire, so he sends his father to ask for her hand, telling him to inform the squire that he is a Master Thief. The squire agrees to the union, but only if the boy proves himself by stealing the roast from the spit on Sunday. The boy catches three hares and releases them at intervals near the squire's kitchen, and the people there, thinking it was one hare, go out to catch it. The boy enters and steals the roast.

When the Master Thief comes to claim his reward, the squire asks him to prove his skill further by playing a trick on the priest. The Master Thief dresses up as an angel and convinces the priest that he has come to take him to heaven. He drags the priest over stones and thorns and throws him into the goose-house, telling him it is purgatory, and then steals all his treasure.

The squire is pleased, but still denies the boy, telling him to steal twelve horses from his stable with twelve grooms in their saddles. The Master Thief disguises himself as an old woman and takes shelter in the stable. When the night grows cold, he drinks brandy against it. The grooms demand some, and he gives them a drugged drink, putting them to sleep, and steals the horses.

The squire denies the boy again, asking if he could steal a horse while the squire is out riding it. The Master Thief says he can. He disguises himself as an old man with a cask of mead and puts his finger in the hole in place of the tap. The squire rides up and asks the disguised boy if he would look in the woods to be sure that the Master Thief did not lurk there. The boy says that he cannot because he has to keep the mead from spilling. The squire takes his place and lends him his horse so he can look, and the boy steals the horse.

The squire denies him once more, asking if he could steal the sheet off his bed and his wife's shift. The Master Thief makes a dummy with the appearance of a man, and when he puts it at the window, the squire shoots it, and the boy lets it drop. Fearing talk, the squire goes to bury it, and the Master Thief, pretending to be the squire, acquires the sheet and the shift on the pretext that they are needed to clean up the blood.

The squire is too afraid of what the thief will steal next, so he lets him marry his daughter.

Analysis

edit"The Master Thief" is classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as ATU 1525 and subtypes.

Folklorist and scholar Richard Dorson cited the opinions of two scholars about the origins of the tale type: Alexander H. Krappe suggested an Egyptian origin for the tale, while W. A. Clouston proposed an Asiatic provenance.[5]

Folklorist Stith Thompson argued that similarities between the European "Master Thief" tales and Native American trickster tales led to the merging of motifs, and the borrowing may have originated from French Canadian tales.[6]

Variants

editFolklorist Stith Thompson argued the story can be found in tale collections from Europe, Asia, and all over the world.[7] Variants of the tale and subtypes of the ATU 1525 are reported to exist in American and English compilations.[8]

Professor Andrejev noted that the tale type 1525A, "The Master Thief", was one of "the most populär tale types" across Ukrainian sources, with 28 variants, as well as "in the Russian material", with 19 versions.[9]

A scholarly inquiry by Italian Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi ("Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage"), produced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, found the existence of variants and subtypes of the tale across Italian sources, grouped under the name Mastro Ladro.[10]

Europe

editFolklorist Joseph Jacobs wrote a reconstruction of the tale, with the same name, in his Europa's Fairy Book, following a formula he specified in his commentaries.[11]

Italy

editAn earlier literary variant is Cassandrino, The Master-Thief, appearing in Straparola's collection The Facetious Nights.[12]

Germany

editThe Grimm Brothers' fairy tales included a version as tale 192. The squire gives the boy the tasks of stealing the horses from the stable, the sheet, his wife's wedding ring, and the parson and clerk from the church as tests of skill and threatens that upon failure, he would hang him. The thief succeeds and leaves the country.

19th century poet and novelist Clemens Brentano collected a variant named Witzenspitzel. His work was translated as Wittysplinter and published in The Diamond Fairy Book.[13][14]

Ireland

editThe Apprentice Thief, an Irish variant, was published anonymously in the compilation The Royal Hibernian Tales.[15]

Irish folklorist Patrick Kennedy also listed Jack, The Cunning Thief as another variant of the Shifty Lad and, by extension, of The Master Thief cycle of stories.[16]

In an Irish variant, the king challenges young Jack, son of Billy Brogan, to steal three things without the King noticing.[17]

In the Irish tale How Jack won a Wife, the Master Thief character, Jack, fulfills the squire's challenges to prove his craft and marries the squire's daughter.[18]

Denmark

editSvend Grundtvig collected a Danish variant, titled Hans Mestertyv.[19]

Greece

editGerman scholar Johann Georg von Hahn compared 6 variants he collected in Greece to the tale in the Brothers Grimm's compilation.[20]

Lithuania

editAccording to Professor Bronislava Kerbelytė, the story of the Master Thief is reported to contain several variants in Lithuania: 284 variants of the AT 1525A, "The Crafty Thief", and 216 variants of AT 1525D, "Theft by Distracting Attention", both versions with and without contamination from other tale types.[21]

Iceland

editJón Árnason's Íslenzkar Þjóðsögur og Æfintýri included a variant, "Grámann."[22]

Asia

editThe motif of impossible thievery can be found in a story engraved in a Babylonian tablet in the tale Poor Man of Nippur.[23][24]

Joseph Jacobs, in his book More Celtic Fairy Tales,[25] mentions an Indian folkloric character named "Sharaf, the Thief" (Sharaf Tsúr; or Ashraf Chor).[26]

Northern India folklore attests to the presence of two variants of the tale involving a king's son as the "Master-Thief".[27]

Americas

editRalph Steele Boggs, following Johannes Bolte and Jiri Polívka's Anmerkungen (1913),[28] listed Spanish picaresque novel Guzmán de Alfarache (1599) as a predecessor of the tale-type.[29]

Anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons collected variants of the tale in Caribbean countries.[30]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Chapman, Frederick T. (1972). "The Master Thief". In Undset, Sigrid (ed.). True and Untrue and Other Norse Tales. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 213–232. ISBN 978-0-8166-7828-0. JSTOR 10.5749/j.ctt4cgg4g.27.

- ^ Asbjørnsen, Peter Christen; Moe, Jørgen (2019). "The Master Thief". The Complete and Original Norwegian Folktales of Asbjørnsen and Moe. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 140–152. doi:10.5749/j.ctvrxk3w0.38. ISBN 978-1-5179-0568-2.

- ^ Dasent, George Webbe. Popular Tales from the Norse. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. 1912. pp. 232–251.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jorg. The Types of International Folktales. 2004.

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. (January 1949). "Polish Wonder Tales of Joe Woods". Western Folklore. 8 (1): 25–52. doi:10.2307/1497158. JSTOR 1497158.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. European Tales Among the North American Indians: a Study In the Migration of Folk-tales. Colorado Springs: Colorado College. 1919. pp. 426–430.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. pp. 174–176. ISBN 978-0520035379

- ^ Baughman, Ernest Warren. Type and Motif-index of the Folktales of England and North America. Indiana University Folklore Series No. 20. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton & Co. 1966. p. 37.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. "A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus". In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 237. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Discoteca di Stato (1975). Alberto Mario Cirese; Liliana Serafini (eds.). Tradizioni orali non cantate: primo inventario nazionale per tipi, motivi o argomenti [Oral and Non Sung Traditions: First National Inventory by Types, Motifs or Topics] (in Italian and English). Ministero dei beni culturali e ambientali. pp. 323–326.

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam's sons. 1916. pp. 245–246.

- ^ Alteria; Waters, W. G. (2012). "Cassandrino the Master-Thief". In Beecher, Donald (ed.). The Pleasant Nights. Vol. 1. University of Toronto Press. pp. 172–198. doi:10.3138/9781442699519. ISBN 978-1-4426-4426-7. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442699519.8.

- ^ [no known authorship]. The Diamond Fairy Book. Illustrations by Frank Cheyne Papé and H. R. Millar. London: Hutchinson. [1897?]. pp. 127–143.

- ^ Blamires, David (2009). "Clemens Brentano's Fairytales". Telling Tales: The Impact of Germany on English Children's Books 1780-1918. pp. 263–274. doi:10.2307/j.ctt5vjt8c.18. ISBN 978-1-906924-11-9.

- ^ The Royal Hibernian Tales: Being a Collection of the Most Entertaining now Extant. Dublin: C. M. Warren. [no date]. pp. 28–39. [1]

- ^ Kennedy, Patrick. The fireside stories of Ireland. Dublin: M'Glashan and Gill: P. Kennedy. 1870. pp. 38–46 and 165.

- ^ MacManus, Seumas. In chimney corners: Merry tales of Irish folk-lore. New York, Doubleday & McClure Co. 1899. pp. 207–223.

- ^ Johnson, Clifton. The Elm-tree Fairy Book: Favorite Fairy Tales. Boston: Little, Brown, 1908. pp. 233–253. [2]

- ^ Grundtvig, Svend. Gamle Danske Minder I Folkemunde. Kjøbenhavn: C. G. Iversen, 1861. pp. 68–72. [3]

- ^ Hahn, Johann Georg von. Griechische und Albanesische Märchen 1–2. München/Berlin: Georg Müller. 1918 [1864]. pp. 290–302.

- ^ Skabeikytė-Kazlauskienė, Gražina. Lithuanian Narrative Folklore: Didactical Guidelines. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University. 2013. p. 41. ISBN 978-9955-21-361-1

- ^ Árnason, Jón (1864). Íslenzkar þjóðsögur og Æfintýri. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. pp. 511–516. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ Johnston, Christopher (1912). "Assyrian and Babylonian Beast Fables". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 28 (2): 81–100. doi:10.1086/369683. JSTOR 528119. S2CID 170540377.

- ^ Jason, Heda; Kempinski, Aharon (January 1981). "How Old Are Folktales?". Fabula. 22 (Jahresband): 1–27. doi:10.1515/fabl.1981.22.1.1. S2CID 162398733.

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. More Celtic Fairy Tales. New York. G. P. Putnam's Sons. 1895. p. 224.

- ^ Knowles, James Hinton. Folk-tales of Kashmir. London: Trübner. 1888. pp. 338–352.

- ^ Crooke, William; Chaube, Pandit Ram Gharib. Folktales from Northern India. Classic Folk and Fairy Tales. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. 2002. pp. 100–103 and 103–105. ISBN 1-57607-698-9

- ^ Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Dritter Band (NR. 121-225). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 379–406.

- ^ Boggs, Ralph Steele. Index of Spanish folktales, classified according to Antti Aarne's "Types of the folktale". Chicago: University of Chicago. 1930. pp. 129–130.

- ^ Parsons, Elsie Worthington Clews. Folk-lore of the Antilles, French And English. Part 3. New York: American Folk-lore Society. 1943. pp. 215–217.

Bibliography

edit- Cosquin, Emmanuel. Contes populaires de Lorraine comparés avec les contes des autres provinces de France et des pays étrangers, et précedés d'un essai sur l'origine et la propagation des contes populaires européens. Tome II. Deuxiéme Tirage. Paris: Vieweg. 1887. pp. 274–281.