"The Meat Fetish" is a 1904 essay by Ernest Crosby on vegetarianism and animal rights. It was subsequently published as a pamphlet the following year, with an additional essay by Élisée Reclus, entitled The Meat Fetish: Two Essays on Vegetarianism.

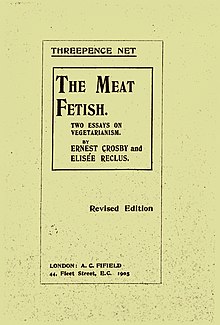

Cover page | |

| Author | Ernest Crosby, Élisée Reclus |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Vegetarianism |

Publication date | 1905 |

| Media type | Print (pamphlet) |

| Pages | 32 |

| OCLC | 616116876 |

| Text | The Meat Fetish at Wikisource |

Background

editErnest Howard Crosby was an American author and reformer, who was an anti-imperialist and labor movement unionist. He was president of the New York Vegetarian Society.[1] Before publishing The Meat Fetish, Crosby had written to the newspaper The New York Times, announcing that he had eaten no meat in eight years, suggesting to replace what was considered the "valuable ingredient in flesh-food, [...] the proteid" with a vegetable source where it was more abundant, such as in cereals and whole-wheat bread, and others.[2]

Prior to writing "The Meat Fetish," Crosby asked artists in Venice, Italy about the agonizing sights, terrifying sounds, and foul smells of the slaughterhouse, compelling imagery which he used to open his essay. It is noted that with these observations, Crosby intended to address the whole of humanity who was nonvegetarian, and not only to write for the artists.[2]

Crosby was the writer Captain Jinks, Hero, as well as several bibliographical works on the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, English socialist and philosopher Edward Carpenter, and American abolitionist and journalist William Lloyd Garrison.[3]

Jean Jacques Élisée Reclus was a French writer, geographer, and anarchist. Reclus travelled during his early adulthood, which led to him writing the multiple volumes of The Earth and its Inhabitants later on in life, while in exile after serving in the National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War.

His vegetarianism, manners, and "intense human sympathy" were noted by The Japan Daily Mail, over any "reasoned-out political creed," as the reasons which led him to live in an anarchist camp.[4] Due to his views on nature conservation, opposition of cruelty to animals, vegetarianism, he was considered an early advocate of social ecology, green anarchism, and animal rights movements.[5] Reclus died the year of the publication of The Meat Fetish.

Publication

editThe essay "The Meat Fetish" was first published in the Humanitarian League's quarterly publication, the Humane Review in 1904.[6] It was published the following year as a 23 centimeter pamphlet by the Millennium Guild, in New York City. It is 12 pages in total length, and also contains "selected passages from his enlightened and voluminous writings." The pamphlet also includes two poems; "The Calf" by Eleanor Baldwin, and "Sadists" by Linn A. E. Gale, which The Occult Press Review calls "rather strong, though it is neither verse nor prose."[7][8] Crosby's essay was also published in the monthly newsletter The Vegetarian Magazine, in 1906.

Reclus' essay, "On Vegetarianism" was first printed in the Humane Review, in January 1901. The British journal Nature describes the essay as one which "champions vegetarianism."[9][10]

The Meat Fetish

editCrosby's essay was again published in 1905, along with an additional essay by Reclus, and sold as a pamphlet entitled The Meat Fetish: Two Essays on Vegetarianism, by the English publishing house of Arthur C. Fifield, at 53 Chancery Lane, London. It was printed by A. Bonner, at 1 & 2 Took's Court. The pamphlet was billed as two "able essays against flesh-eating" by the publisher, appearing in the advertisement section of the work Where Men Decay.[11] A new edition, which was 32 pages in total length, was printed in the same year by A. C. Fifield at 44 Fleet Street, E. C., London.[12] This edition was also part of the Humanitarian League New Series.[13] The cost of one pamphlet was 3 pennies, with ½ penny for postage.[12]

The Meat Fetish: Two Essays on Vegetarianism was then published by the Public Publishing Company, at the First National Bank Building, in Chicago, Illinois. It was described as an "interesting and comprehensive primer on vegetarianism" in an advertisement taken out in the periodical Land and Freedom. The advertisement column also directs the reader to "Send the Packers Packing! Why eat filth when it is quite unnecessary? Learn to do without by reading The Meat Fetish."[14] The identical advertisement also appears in the periodicals Single Tax Review, as well as The Public. In 1907, the cost for one copy of The Meat Fetish pamphlet was post-free with 10 cents of postage stamps, or twelve copies for 1 dollar with postage paid.[14]

Four editions of The Meat Fetish: Two Essays on Vegetarianism are held at public and university libraries in Canada, the United States, Scotland, Great Britain, Spain, Germany, and the Netherlands.[15]

Content

editThe pamphlet of The Meat Fetish: Two Essays on Vegetarianism opens with two pages of advertisements, the first page being a list of the Humanitarian League's New Series publications, and the second being a list of books and pamphlets by Crosby. It is then divided into two sections, with the essay by Crosby appearing before the essay by Reclus. Appearing at the end of the pamphlet is a second set of advertisements; the first page being a listing of the Simple Life Series publications, and the second page being a list of the Humanitarian League's Old Series publications.

Crosby's essay

editThe beginning of the essay by Crosby, "The Meat Fetish" describes three slaughter-houses which he encountered throughout his life, in New Hampshire, near Cleopatra's palace in the Mediterranean, and at Venice, in graphic detail. On the butchers' overcoming their engagement the animals which they slaughter, he notes that it is "futile to preach humanity to men engaged in such a trade. You or I, enlisted in such a profession, would act in the same way." He continues that it is "brutalising work as well as cruel work," adding that it is the society which creates the demand for it who are responsible.[16] Crosby asks shortly thereafter, "how many of your friends are there whom on this score alone you would be willing to eat? I am quite sure that if we were cannibals we should insist on eating people whom we had not known."[17] On this slaughtering, he points out that the body after death, whether a man, ox, or dog, is a corpse, and "nothing but a corpse [which] we feel instinctively [...] is unclean."[17]

Crosby then notes that recent medical investigations have attributed leprosy and scurvy to the eating of animal food, and suggests that it may not be long before cancer is traced to the same origin.[18] This is due, he ascertains, to man not being naturally carnivorous, with its jaws hung like those of a cow, horse and camel, for grinding, and also that man has the long intestines of the graminivorous animals, and not the short intestines of the carnivora.[19][20]

Looking forward, Crosby predicts that when man ceases killing animals, the world may become crowded with them, which, for him, conjures up pictures of cities packed with sheep or deer, and countrysides overflowing with cows.[21] He ends the essay with writing that just as man arose out of cannibalism, "we are bound just as surely to advance beyond the system of quasi-cannibalism in which we live."[22]

Reclus' essay

editReclus' essay "On Vegetarianism opens with the disclaimer that he is neither a chemist or doctor, describing his content as a personal impression.[23] After recounting a visit to the slaughter-house he made as a child, he describes how the slaughtered animal has transformed to meet our dietary needs, as has the ways of man. Using the atrocities in China at the turn of the 20th century, Reclus asks the reader, "How can it be that men having had the happiness of being caressed by their mother, and taught in school the words "justice" and "kindess" [take] pleasure in tying Chinese together by their garments and their pigtails before throwing them into a river? [These] men like ourselves, who study and read as we do, who have brothers, friends, a wife or a sweetheart [...] are in the habit of praising th bleeding flesh as a generator of health, strength, and intelligence."[24]

In the closing paragraphs of his essay, Reclus writes that "we wish to preserve [animals] as respected fellow-workers, or simply as companions in the joy of life and friendship," adding that "it is not for us to found a new religion, and to hamper ourselves with a fectarian dogma; it is a question of making our existence as beautiful as possible, and in harmony."[25] He ends the essay with 'the Latin phrase "Omne vivum ex vivo," or "all life from life."[26]

Reviews

editIn Vegetarian America: A History, Iacobbo and Iacobbo said that Crosby's "essay is one of the most powerful on the topic of vegetarianism published by an American during the twentieth century," adding that Crosby's "combination of smooth prose and passion with earnestness and erudition has had few peers".[2] Soundview said that the Meat Fetish is "one of the most powerful arguments in favor of a vegetarian diet we have yet seen," and London's The Humanitarian writes that "his plea for abstinence from flesh-food is among the best with which we are acquainted".[14] The University Digest noted that his objection to the custom of the meat diet, is that it "involves cruelty, breeds disease, and withal an entirely unwholesome food for man".[19] The Humane Review called it "one of the very best things ever written in advocacy of a vegetarian diet".[27]

It has been cited in several works, such as Charlotte Alston's 2013 work, Tolstoy and his Disciples, and Leela Gandhi's 2006 work, Affective Communities: Anticolonial Thought, Fin-de-Siècle Radicalism, and the Politics of Friendship.[28]

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Edmundson 2014.

- ^ a b c Iacobbo & Iacobbo 2004, p. 146.

- ^ Worldcat Staff 2020.

- ^ The Japan Daily Mail Staff 1905, p. 229.

- ^ Hochschartner 2014.

- ^ Fox 1999, p. 217.

- ^ Worldcat Staff 2003.

- ^ The Occult Press Review Staff 1922, p. 36.

- ^ The Anarchist Library Staff 2009.

- ^ Nature Staff 1901, p. 101.

- ^ Pedder 1908, p. 158.

- ^ a b Monteuuis 1906, p. 57.

- ^ Bell 1907, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Land and Freedom Staff 1907, p. 62.

- ^ Worldcat Staff 2003a.

- ^ Crosby & Reclus 1905, p. 7.

- ^ a b Crosby & Reclus 1905, p. 9.

- ^ Crosby & Reclus 1905, p. 10.

- ^ a b The University Digest Staff 1906, p. 38.

- ^ Crosby & Reclus 1905, p. 12.

- ^ Crosby & Reclus 1905, p. 16.

- ^ Crosby & Reclus 1905, p. 22.

- ^ Crosby & Reclus 1905, p. 23.

- ^ Crosby & Reclus 1905, p. 26–27.

- ^ Crosby & Reclus 1905, p. 29–30.

- ^ Crosby & Reclus 1905, p. 32.

- ^ Bell 1907, p. 14.

- ^ Gandhi 2006, p. 113.

Sources

edit- The Anarchist Library Staff (3 March 2009), "On Vegetarianism", The Anarchist Library

- Bell, E. (1907), "Ernest Crosby", The Humane Review, vol. 7–8

- Crosby, Ernest; Reclus, Elisée (1905). . A. C. Fifield – via Wikisource.

- Edmundson, John (8 December 2014), "Vegan Slaughterhouse Reflections", HappyCow

- Fox, Michael Allen (1999), Deep Vegetarianism, Temple University Press, ISBN 9781592138142

- Gandhi, Leela (11 January 2006), Affective Communities: Anticolonial Thought, Fin-de-Siècle Radicalism, and the Politics of Friendship, Duke University Press, ISBN 0822337150

- Hochschartner, Jon (19 March 2014), "The Vegetarian Communard", CounterPunch, retrieved 9 August 2023

- Iacobbo, Karen; Iacobbo, Michael (2004), Vegetarian America: A History, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 9780275975197

- The Japan Daily Mail Staff (26 August 1905), "News of the Week", The Japan Daily Mail, vol. 44, A.H. Blackwell

- Land and Freedom Staff (1907), "Advertisements", Land and Freedom, vol. 7, Single Tax Publishing Company

- Monteuuis, Albert (1906), Curdled Milk, a Natural Key to Health and Long Life, Simple Life, vol. 24, A. C. Fifield

- Nature Staff (1901), The Human Review, vol. 64, Macmillan Journals Limited

- The Occult Press Review Staff (October–November 1922), "The Vegetarian Messenger" (PDF), The Occult Press Review, vol. 1, no. 3–4

- Pedder, Digby Cotes (1908), Where Men Decay: A Survey of Present Rural Conditions

- The University Digest Staff (1906), The University Digest, vol. 1–2, University Research Extension

- Worldcat Staff (2003), "The Meat Fetish", WorldCat, OCLC 567478581

- Worldcat Staff (2003a), "The Meat Fetish: Two Essays on Vegetarianism", WorldCat, OCLC 616116876

- Worldcat Staff (2020), "Crosby, Ernest 1856-1907", WorldCat

External links

edit- The full text of The Meat Fetish at Wikisource

- Media related to The Meat Fetish at Wikimedia Commons

- The Meat Fetish in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- The Meat Fetish: Two Essays on Vegetarianism in libraries (WorldCat catalog)