William Robertson Davies CC OOnt FRSL FRSC (28 August 1913 – 2 December 1995) was a Canadian novelist, playwright, critic, journalist, and professor. He was one of Canada's best known and most popular authors and one of its most distinguished "men of letters", a term Davies gladly accepted for himself.[1] Davies was the founding Master of Massey College, a graduate residential college associated with the University of Toronto.

Robertson Davies | |

|---|---|

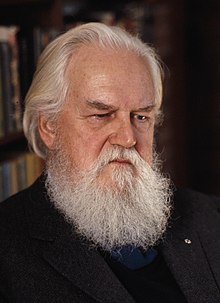

Davies in 1982 | |

| Born | 28 August 1913 Thamesville, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | 2 December 1995 (aged 82) Orangeville, Ontario, Canada |

| Occupation | Journalist, playwright, professor, critic, novelist |

| Alma mater | Queen's University (did not graduate) Balliol College, Oxford |

| Genre | Novels, plays, essays and reviews |

| Notable works | The Deptford Trilogy, The Cornish Trilogy, The Salterton Trilogy |

| Spouse | Brenda Ethel Davies (m. 1940, 1917–2013) |

| Children | 3 |

Biography

editEarly life

editDavies was born in Thamesville, Ontario, the third son of William Rupert Davies and Florence Sheppard McKay.[2] Growing up, Davies was surrounded by books and lively language. His father, a member of the Canadian Senate from 1942 to his death in 1967, was a newspaperman from Welshpool, Wales, and both parents were voracious readers. He followed in their footsteps and read everything he could. He also participated in theatrical productions as a child, where he developed a lifelong interest in drama.

He spent his formative years in Renfrew, Ontario (and renamed it as "Blairlogie", in his novel What's Bred in the Bone); many of the novel's characters are named after families he knew there. He attended Upper Canada College in Toronto from 1926 to 1932 and while there attended services at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene.[3] He would later leave the Presbyterian Church and join Anglicanism over objections to Calvinist theology. Davies later used his experience of the ceremonial of High Mass at St. Mary Magdalene's in his novel The Cunning Man.

After Upper Canada College, he studied at Queen's University at Kingston, Ontario, from 1932 until 1935. According to the Queen's University Journal Davies enrolled as a special student not working towards a degree, because he was unable to pass the mathematics component of Queen's entrance exam.[4] At Queen's he wrote for the student paper, The Queen's Journal, where he wrote a literary column. He left Canada to study at Balliol College, Oxford, where he received a BLitt degree in 1938. The next year he published his thesis, Shakespeare's Boy Actors, and embarked on an acting career outside London. In 1940, he played small roles and did literary work for the director at the Old Vic Repertory Company in London. Also that year, Davies married Australian Brenda Mathews, whom he had met at Oxford, and who was then working as stage manager for the theatre.[2] They spent their honeymoon in the Welsh countryside at Fronfraith Hall, Abermule, Montgomery, the family house owned by Rupert Davies.[5]

Davies's early life provided him with themes and material to which he would often return in his later work, including the theme of Canadians returning to England to finish their education, and the theatre.

Middle years

editDavies and his new bride returned to Canada in 1940, where he took the position of literary editor at Saturday Night magazine. Two years later, he became editor of the Peterborough Examiner in the small city of Peterborough, Ontario, northeast of Toronto. Again he was able to mine his experiences here for many of the characters and situations which later appeared in his plays and novels.[2]

Davies, along with family members William Rupert Davies and Arthur Davies, purchased several media outlets. Along with the Examiner newspaper, they owned the Kingston Whig-Standard newspaper, CHEX-AM, CKWS-AM, CHEX-TV, and CKWS-TV.

During his tenure as editor of the Examiner, which lasted from 1942 to 1955 (he subsequently served as publisher from 1955 to 1965), Davies published a total of 18 books, produced several of his own plays, and wrote articles for various journals.[2] Davies set out his theory of acting in his Shakespeare for Young Players (1947), and then put theory into practice when he wrote Eros at Breakfast, a one-act play which was named best Canadian play of the year by the 1948 Dominion Drama Festival.[6]

Eros at Breakfast was followed by Fortune, My Foe in 1949 and At My Heart's Core, a three-act play, in 1950. Meanwhile, Davies was writing humorous essays in the Examiner under the pseudonym Samuel Marchbanks. Some of these were collected and published in The Diary of Samuel Marchbanks (1947), The Table Talk of Samuel Marchbanks (1949), and later in Samuel Marchbanks' Almanack (1967). An omnibus edition of the three Marchbanks books, with new notes by the author, was published under the title The Papers of Samuel Marchbanks in 1985.[7]

During the 1950s, Davies played a major role in launching the Stratford Shakespearean Festival of Canada. He served on the Festival's board of governors, and collaborated with the Festival's director, Sir Tyrone Guthrie, in publishing three books about the Festival's early years.[2][8]

Although his first love was drama and he had achieved some success with his occasional humorous essays, Davies found his greatest success in fiction. His first three novels, which later became known as The Salterton Trilogy, were Tempest-Tost (1951, originally conceived as a play), Leaven of Malice (1954, also the basis of the unsuccessful play Love and Libel) which won the Stephen Leacock Award for Humour, and A Mixture of Frailties (1958).[7] These novels explored the difficulty of sustaining a cultural life in Canada, and life on a small-town newspaper, subjects of which Davies had first-hand knowledge. In a 1959 essay on Nabokov's Lolita, he wrote that she was a corrupt child taking advantage of a weak adult.

1960s

editIn 1960, Davies joined Trinity College at the University of Toronto, where he would teach literature until 1981. The following year he published a collection of essays on literature, A Voice From the Attic, and was awarded the Lorne Pierce Medal for his literary achievements.[2]

In 1963, he became the Master of Massey College, the University of Toronto's new graduate college.[2] During his stint as Master, he initiated a tradition of writing and telling ghost stories at the yearly Christmas celebrations.[9] These stories were later collected in the book High Spirits (1982).[7]

1970s

editDavies drew on his interest in Jungian psychology to create Fifth Business (1970), a novel that relies heavily on Davies's own experiences, his love of myth and magic, and his knowledge of small-town mores. The narrator, like Davies, is of immigrant Canadian background, with a father who runs the town paper. The book's characters act in roles that roughly correspond to Jungian archetypes according to Davies's belief in the predominance of spirit over the things of the world.[2]

Davies built on the success of Fifth Business with two more novels: The Manticore (1972), a novel cast largely in the form of a Jungian analysis (for which he received that year's Governor General's Literary Award),[10] and World of Wonders (1975). Together these three books came to be known as The Deptford Trilogy.

1980s and 1990s

editWhen Davies retired from his position at the university, his seventh novel, a satire of academic life, The Rebel Angels (1981), was published, followed by What's Bred in the Bone (1985) which was short-listed for the Booker Prize for fiction in 1986.[10] The Lyre of Orpheus (1988) follows these two books in what became known as The Cornish Trilogy.[7]

During his retirement from academe he continued to write novels which further established him as a major figure in the literary world: Murther and Walking Spirits (1991) and The Cunning Man (1994).[7] A third novel in what would have been a further trilogy – the Toronto Trilogy – was in progress at the time of Davies's death.[2] He also realized a long-held dream when he penned the libretto to Randolph Peters' opera: The Golden Ass, based on The Metamorphoses of Lucius Apuleius, just like that written by one of the characters in Davies's 1958 A Mixture of Frailties. The opera was performed by the Canadian Opera Company at the Hummingbird Centre in Toronto, in April 1999, several years after Davies's death.[11]

In its obituary, The Times wrote: "Davies encompassed all the great elements of life ... His novels combined deep seriousness and psychological inquiry with fantasy and exuberant mirth."[12] He remained close friends with John Kenneth Galbraith, attending Galbraith's eighty-fifth birthday party in Boston in 1993,[13] and became so close a friend and colleague of the American novelist John Irving that Irving gave one of the scripture readings at Davies's funeral in the chapel of Trinity College, Toronto. He also wrote in support of Salman Rushdie when the latter was threatened by a fatwā from Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran in reaction to supposed anti-Islam expression in his novel The Satanic Verses.[14]

Personal life

editDavies was married to Brenda Ethel Davies (1917–2013) in 1940 and survived by four grandchildren and three great-grandchildren from his three daughters Miranda Davies, Rosamond Bailey and author Jennifer Surridge.[15][16]

Davies never learned to drive.[17] His wife Brenda routinely drove him to events and other excursions.

Awards and recognition

edit- Won the Dominion Drama Festival Award for best Canadian play in 1948 for Eros at Breakfast.

- Won the Stephen Leacock Award for Humour in 1955 for Leaven of Malice.

- Won the Lorne Pierce Medal for his literary achievements in 1961.

- Won the Governor-General's Literary Award in the English language fiction category in 1972 for The Manticore.

- Short-listed for the Booker Prize for Fiction in 1986 for What's Bred in the Bone.

- Honorary Doctor of Letters, University of Oxford, 1991.[2]

- First Canadian to become an Honorary Member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.[2]

- Companion of the Order of Canada.[2]

- Park in Toronto named after him in 2007.[18]

Works

editNovels

edit- The Salterton Trilogy

- Tempest-Tost (1951)

- Leaven of Malice (1954)

- A Mixture of Frailties (1958)

- The Deptford Trilogy

- Fifth Business (1970)

- The Manticore (1972)

- World of Wonders (1975)

- The Cornish Trilogy

- The Rebel Angels (1981)

- What's Bred in the Bone (1985)

- The Lyre of Orpheus (1988)

- The "Toronto Trilogy" (incomplete)

- Murther and Walking Spirits (1991)

- The Cunning Man (1994)

Essays

editFictional essays

- The Diary of Samuel Marchbanks (1947)

- The Table Talk of Samuel Marchbanks (1949)

- Samuel Marchbanks' Almanack (1967)

edited by the author into:

Criticism

- Shakespeare's Boy Actors (1939) (as W. Robertson Davies)

- Shakespeare for Young Players: A Junior Course (1942)

- Renown at Stratford (1953) (with Tyrone Guthrie)

- Twice Have the Trumpets Sounded (1954) (with Tyrone Guthrie)

- Thrice the Brindled Cat Hath Mew'd (1955) (with Tyrone Guthrie)

- A Voice From the Attic (1960) also published as The Personal Art

- A Feast of Stephen (1970)

- Stephen Leacock (1970)

- One Half of Robertson Davies (1977)

- The Enthusiasms of Robertson Davies (1979; revised 1990) (edited by Judith Skelton Grant)

- The Well-Tempered Critic (1981) (edited by Judith Skelton Grant)

- The Mirror of Nature (1983)

- Reading and Writing (1993) (two essays, later collected in The Merry Heart)

- The Merry Heart (1996)

- Happy Alchemy (1997) (edited by Jennifer Surridge and Brenda Davies)

Plays

edit- Overlaid (1948)

- Eros at Breakfast (1948)

- Hope Deferred (1948)

- King Phoenix (1948)

- At the Gates of the Righteous (1949)

- Fortune My Foe (1949)

- The Voice of the People (1949)

- At My Heart's Core (1950)

- A Masque of Aesop (1952)

- Hunting Stuart (1955)

- A Jig for the Gypsy (1955)

- General Confession (1956)

- A Masque of Mr. Punch (1963)

- Question Time (1975)

- Brothers in the Black Art (1981)

Short story collection

edit- High Spirits (1982)

Libretti

edit- Doctor Canon's Cure (1982)

- Jezebel (1993)

- The Golden Ass (1999)

Letters and diaries

edit- For Your Eye Alone (2000) (edited by Judith Skelton Grant)

- Discoveries (2002) (edited by Judith Skelton Grant)

- A Celtic Temperament: Robertson Davies as Diarist (2015) (edited by Jennifer Surridge and Ramsay Derry)

Collections

edit- Conversations with Robertson Davies (1989) (Edited by J. Madison Davis)

- The Quotable Robertson Davies: The Wit and Wisdom of the Master (2005) (collected by James Channing Shaw)

- The Merry Heart: Reflections on Reading Writing, and the World of Books (New York: Viking, 1997). ISBN 9780670873661

References

edit- ^ Responding to Peter Gzowski's query as to whether he accepted the label, Davies said, "I would be delighted to accept it. In fact, I think it's an entirely honourable and desirable title, but you know people are beginning to despise it." Davis, J. Madison (ed.) (1989). Conversations with Robertson Davies. Mississippi University Press. p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Robertson Davies". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Penguin USA: Book Club Reading Guides: The Cunning Man Archived 27 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Labiba Haque (29 June 2010). "Canadian classics come to Queen's: Famed author Robertson Davies' collection set to be displayed in library". Queen's University Journal. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ English, E., ed. (1999). A Collected History of the Communities of Llandyssil, Abermule and Llanmerewig. Llandyssil Community Council. Section 6, pt. 1.

- ^ Stone-Blackburn, Susan (1985). Robertson Davies, Playwright: A Search for the Self on the Canadian Stage. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-0211-1.

- ^ a b c d e "Robertson Davies Canadian Books & Authors". canadianauthors.net. Canadian Books & Authors. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ "Stratford Festival". stratfordfestival.ca. Stratford Festival. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Spedoni, Carl; Grant, Judith Skelton (2014). A Bibliography of Robertson Davies. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1442667280.

- ^ a b Corrigan, David Rockne (28 August 2013). "Canadian Novelist Robertson Davies Honoured with Postage Stamp". National Post. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ Friedlander, Mira (17 May 1999). "The Golden Ass". Variety. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ "Robertson Davies". Penguin.ca. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

- ^ Parker, Richard (2005). John Kenneth Galbraith: His Life, His Politics, His Economics. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 532ff photos.

- ^ Appignanesi, Lisa; Maitland, Sara, eds. (1990). The Rushdie File. Syracuse University Press. p. 172. ISBN 0-8156-2494-8. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Ptashnick, Victoria (10 January 2013). "Robertson Davies' wife, Brenda Davies, dies at age 95". The Star. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016.

- ^ Shanahan, Noreen (7 February 2013). "Brenda Davies (1917–2013): Robertson Davies' mate and manager". Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016.

- ^

Merilyn Simonds (25 November 2015). "A great Canadian diarist". Kingston Whig Standard. Kingston, Ontario. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

'Their marriage was quite a love story and she was incredibly supportive. She was his first reader, and she drove him everywhere — he never learned to drive — and she organized his life to his convenience. That's why we included letters from when he went to Ireland. He was not very good at being away from her.'

- ^ Ross, Val (31 May 2007). "Park named after Robertson Davies". Globe and Mail.

Further reading

edit- Grant, Judith Skelton (1994). Robertson Davies: Man of Myth. Toronto: Viking. ISBN 0-670-82557-3.

External links

edit- Robertson Davies at the Internet Book List

- Robertson Davies at IMDb

- Robertson Davies' Personal Library (Queen's University at Kingston)

- Robertson Davies fonds (R4939) at Library and Archives Canada