The Rabbit's Foot Company, also known as the Rabbit('s) Foot Minstrels and colloquially as "The Foots", was a long-running minstrel and variety troupe that toured as a tent show in the American South between 1900 and the late 1950s. It was established by Pat Chappelle, an African-American entrepreneur in Tampa, Florida.

After his death in 1911, Fred Swift Wolcott bought the company. He was the white owner of a festival touring group in South Carolina. Wolcott was owner and manager of the company until 1950. It was the base for the careers of many leading African-American musicians and entertainers, including Arthur "Happy" Howe, Ma Rainey, Ida Cox, Bessie Smith, Butterbeans and Susie, Tim Moore, Big Joe Williams, Louis Jordan, Brownie McGhee, Rufus Thomas, and Charles Neville.

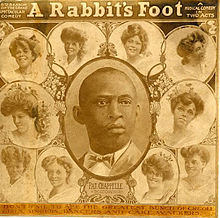

Pat Chappelle's Rabbit's Foot Company, 1900–1911

editThe company was founded, organized, originally owned, and managed by Pat Chappelle (1869–1911), an African-American former string band guitar player and entrepreneur. Originally from Jacksonville, Florida, he established a small chain of theatres in the late 1890s.[1][2] In 1898, Chappelle organized his first traveling show, the Imperial Colored Minstrels (or Famous Imperial Minstrels),[3] which featured the comedian Arthur "Happy" Howe and toured successfully around the South.[4][5] Chappelle also opened the Excelsior Hall in Jacksonville, the first black-owned theater in the South, which reportedly seated 500 people.[1] In 1899, he closed the theater and moved to Tampa, where he and the African-American entrepreneur R. S. Donaldson opened a new vaudeville house, the Buckingham, in the Fort Brooke neighborhood, soon followed by a second theatre, the Mascotte.[1][3]

The success of their shows at the Buckingham and Mascotte theatres led Chappelle and Donaldson to announce their intention, in early 1900, to establish a traveling vaudeville show. Chappelle commissioned Frank Dumont (1848–1919), of the Eleventh Street Theater in Philadelphia, to write a show for the new company. Dumont was an experienced writer for minstrel shows, who "wrote perhaps hundreds of skits and plays".[6] A Rabbit's Foot had little plot; a newspaper at the time said that it "is an excellent vehicle for the presentation of an abundant amount of rag-time, sweet Southern melodies, witty dialogue, buck dancing, cake walks, and numerous novelties".[1]

In May 1900, Chappelle and Donaldson advertised for "60 Colored Performers... Only those with reputation, male, female and juvenile of every description, Novelty Acts, Headliners, etc., for our new play 'A Rabbit's Foot'.... We will travel in our own train of hotel cars, and will exhibit under canvas". In summer 1900, Chappelle decided to put the show into theatres rather than under tents, first in Paterson, New Jersey, and then in Brooklyn, New York. However, his bandmaster, Frank Clermont, left the company, his partnership with Donaldson dissolved, and business was poor.[1] In October 1901, the company launched its second season, with a roster of performers again led by the comedian Arthur "Happy" Howe (1873-1930), and toured in Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and Florida. The show grew in popularity throughout the early years of the century, playing in both theatres and tents.[1][3] Trading as Chappelle Bros.,[5] Pat Chappelle and his brothers, James E. Chappelle and Lewis W. Chappelle, rapidly organised a small vaudeville circuit, including theatre venues in Savannah, Georgia, Jacksonville and Tampa. By 1902 it was said that the Chappelle brothers had full control of the African-American vaudeville business in that part of the country, "able to give from 12 to 14 weeks [of employment] to at least 75 performers and musicians" each season.[4]

Chappelle stated, late in 1902, that he had "accomplished what no other Negro has done – he has successfully run a Negro show without the help of a single white man."[1] As his business grew, he was able to own and manage multiple tent shows, and the Rabbit's Foot Company traveled to as many as sixteen states in a season. Chappelle was known for creating exciting shows, often coordinated with parades, or parades were organized around his show's appearances, and the Rabbit's Foot Company drew large crowds. The shows included minstrel performances, dancers, circus acts including "daring aerialists", comedy, musical ensembles, drama and classic opera.[7] The show was known as one of the few "authentic negro" vaudeville shows around, as all its performers were African American. It traveled most successfully in the southeast and southwest, and also to Manhattan and Coney Island in New York.[8] Chappelle also established an all-black baseball team, which toured with the company and played the local team in each city the company visited. The team operated until at least 1916.[1][3]

By 1904, the Rabbit's Foot show featured more than 60 quality performers,[9] had expanded to fill three Pullman railroad carriages, and was describing itself as "the leading Negro show in America".[10] For the 1904–1905 season, the company included week-long stands in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland. Two of its most popular performers were the singing comedian Charles "Cuba" Santana and the trombonist Amos Gilliard. After the latter moved to Rusco and Holland's Georgia Minstrels, he claimed that Chappelle and his brothers had threatened him at gunpoint before throwing him off the company train.[1]

Performer William Rainey brought his young bride, Gertrude – later known as "Ma Rainey" – to join the company in 1906.[1] That year, Chappelle launched a second traveling tent company, the Funny Folks Comedy Company, with performers alternating between the two companies. The business continued to expand. Following a dispute, his brothers Lewis and James Chappelle left the company around 1907.

In August 1908 one of the Pullman carriages used by the show burned to the ground in Shelby, North Carolina, killing several vaudeville entertainers who were sleeping. The fire started after one of the company horses kicked over a tank of gasoline near a cooking stove. Chappelle quickly ordered a new carriage and eighty-foot round tent so the show could go on the following week.[11]

Pat Chappelle died from an unspecified illness in October 1911, aged 42. At his death, he was said to be "one of the wealthiest colored citizens of Jacksonville, Fla., owning much real estate".[12] His widow, Rosa, remarried and sold the Rabbit's Foot Company in 1912 as a going concern.[1]

F. S. Wolcott's Original Rabbit's Foot Minstrels, 1912–1959

editThe Rabbit's Foot Company was bought in 1912 by Fred Swift Wolcott (1882–1967), a white farmer originally from Michigan. He owned a small carnival company, F. S. Wolcott Carnivals, and put on a touring show, "F. S. Wolcott's Fun Factory", based in Columbia, South Carolina.[13]

Wolcott maintained the Rabbit's Foot company as a touring show,[14] working as both owner and manager, and attracted new talent, including the blues singer Ida Cox, who joined the company in 1913. Ma Rainey recruited the young Bessie Smith for the troupe and worked with her until Smith left in 1915. Wolcott moved the show's touring base to his 1,000-acre Glen Sade Plantation, outside Port Gibson, Mississippi, in 1918. Company offices were located in the center of the trading town. Wolcott began to refer to the show as a "minstrel show" – a term Chappelle had eschewed. Company member trombonist Leon "Pee Wee" Whittaker, described Wolcott as "a good man" who looked after his performers.[1]

Each spring, musicians from around the country assembled in Port Gibson to create a musical, comedy, and variety show to perform under canvas. In his book The Story of the Blues, Paul Oliver wrote:[15]

The 'Foots' travelled in two cars and had an 80' x 110' tent which was raised by the roustabouts and canvassmen, while a brass band would parade in town to advertise the coming of the show....The stage would be of boards on a folding frame and Coleman lanterns – gasoline mantle lamps – acted as footlights. There were no microphones; the weaker voiced singers used a megaphone, but most of the featured women blues singers scorned such aids to volume.

The company, by this time known as "F. S. Wolcott's Original Rabbit's Foot Company" or "F. S. Wolcott’s Original Rabbit's Foot Minstrels", continued to perform annual tours through the 1920s and 1930s, playing small towns during the week and bigger cities on weekends. Louis Jordan performed with the troupe in the 1920s, sometimes with his father, a bandleader. Other performers with the company in the 1930s included the young Rufus Thomas, George Guesnon, and Leon "Pee Wee" Whittaker. Later, Maxwell Street Jimmy Davis also toured with the troupe.[16]

In 1943 Wolcott placed an advertisement in Billboard, describing the show as "the Greatest Colored Show on Earth" and seeking "Comedians, Singers, Dancers, Chorus Girls, Novelty Acts and Musicians".[17] Wolcott remained its general manager and owner until he sold the company in 1950, to Earl Hendren, of Erwin, Tennessee.[1]

In turn, Hendren sold the operation in 1955 to Eddie Moran, of Monroe, Louisiana. It was based there in its final years.[18] In 1956, it was reported to be still trading under Wolcott's name and "playing under canvas and making mostly one-day stands... bringing live entertainment of a style most show people don't dream still exists and flourishes."[19] The show at that time featured blues singer Mary Smith and comedian Memphis Lewis; it had a payroll of 50, including a ten-strong band. Performances included "up-to-the-minute rock-and-roll" and an "exotic dancer".[19] Records suggest that the company's last performance was in 1959.[20] The company's trucks, buses and trailers were seized and sold by the sheriff of Ouachita Parish in Monroe in 1960, under a writ of fieri facias, to satisfy taxes and debt.[21]

Commemoration

editA historical marker has been placed in Port Gibson, Mississippi, by the Mississippi Blues Commission, as part of the Mississippi Blues Trail. Marking the site of the former offices, it commemorates the contribution of the Rabbit's Foot Company to the development of the blues in Mississippi.[20]

In 2006, an exhibition, The Blues in Claiborne County: From Rabbit Foot Minstrels to Blues and Cruise, was shown in Port Gibson, exploring the history of the show, with artifacts and memorabilia.[18]

Cultural references

editThe song "The W. S. Walcott Medicine Show", on the Band's 1970 album Stage Fright, written by Robbie Robertson, was based on stories Levon Helm had told him about the Wolcott troupe. It had regularly performed in Arkansas when Helm was growing up there.[22]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Abbott, Lynn; Seroff, Doug, eds. (2009). Ragged But Right: Black Traveling Shows, Coon Songs, and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 248–289.

- ^ Rivers, Larry Eugene; Brown, Canter Jr. (2007). "The Art of Gathering a Crowd: Florida's Pat Chappelle and the Origins of Black-Owned Vaudeville". Journal of African American History. 92 (2): 169–190. doi:10.1086/JAAHv92n2p169. JSTOR 20064178. S2CID 148681678.

- ^ a b c d Sampson, Henry T. (1980). Blacks in Blackface: A Sourcebook on Early Black Musical Shows. 2013 ed. Scarecrow Press. pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Peterson, Bernard L. (1997). The African American Theatre Directory, 1816–1960: A Comprehensive Guide to Early Black Theatre Organizations, Companies, Theatres, and Performing Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 104.

- ^ a b Peterson, Bernard L. (2001). Profiles of African American Stage Performers and Theatre People, 1816–1960. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 51.

- ^ Historical Society of Pennsylvania. "Collection 3054: Frank Dumont (1848–1919), Minstrelsy Scrapbook.

- ^ "Rabbit's Foot Comedy Company; T. G. Williams; William Mosely; Ross Jackson; Sam Catlett; Mr. Chappelle". News/Opinion. The Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana). October 7, 1905. p. 6.

- ^ "The Stage." News/Opinion. The Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana). June 9, 1900. p. 5.

- ^ "The Stage." News/Opinion (Lakeview, N.J., opening). The Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana). March 9, 1900. p. 5.

- ^ "Wait for the Big Show". The Afro American. April 23, 1904. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ Smith, Peter Dunbaugh (2006). Ashley Street Blues: Racial Uplift and the Commodification of Vernacular Performance in LaVilla Florida, 1896–1916 Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. Dissertation, Florida State University, College of Arts and Science.

- ^ The New York Age. November 16, 1911. p. 2. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Sampson, Henry T. (2013). Blacks in Blackface: A Sourcebook on Early Black Musical Shows. Scarecrow Press. p. 1167.

- ^ "Notes: Rabbit Foot Company". The Freeman. 26 April 1913. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ Paul Oliver, Paul (1972). The Story of the Blues. ISBN 0-14-003509-5.

- ^ Cheseborough, Steve (2009). Blues Traveling: The Holy Sites of Delta Blues (3rd ed.). Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-60473-124-8.

- ^ Billboard. June 5, 1943. p. 27.

- ^ a b "Rabbit Foot Minstrel Exhibit in Port Gibson Until September 30, 2006". h-southern-music. Retrieved 10 July 2014

- ^ a b Parkinson, Tom (1956). "Ol' Rabbit Foot Still Hoppin' Thru South". Billboard. May 19, 1956. pp. 1, 38.

- ^ a b "Rabbit Foot Minstrels". Msbluestrail.org. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- ^ "Sheriff's Sale... Eddie Moran DBA Southern Valley Shows or Rabbit Foot Minstrels". Monroe News Star. October 4, 1960. p. 17.

- ^ Helm, Levon; Davis, Stephen (1993). This Wheel's on Fire: Levon Helm and the Story of the Band. London: Plexus.