Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States, and in one rural county in Arkansas. The term "Red Summer" was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who had been employed as a field secretary by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 1916. In 1919, he organized peaceful protests against the racial violence.[1][2]

| Part of the First Red Scare and nadir of American race relations | |

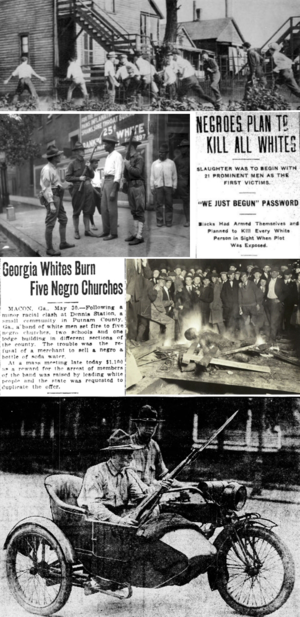

(clockwise from the top)

| |

| Date | 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | United States |

| Target | African Americans |

| Participants | Mostly white mobs attacking African-Americans |

| Outcome | White supremacist terrorist attacks, riots, and murders against black Americans across the United States |

| Deaths | Hundreds |

| Inquest |

|

In most instances, attacks consisted of white-on-black violence. Numerous African Americans fought back, notably in the Chicago and Washington, D.C., race riots, which resulted in 38 and 15 deaths respectively, along with even more injuries, and extensive property damage in Chicago.[3] Still, the highest number of fatalities occurred in the rural area around Elaine, Arkansas, where an estimated 100–240 black people and five white people were killed—an event now known as the Elaine massacre.

The anti-black riots developed from a variety of post-World War I social tensions, generally related to the demobilization of both black and white members of the United States Armed Forces following World War I; an economic slump; and increased competition in the job and housing markets between ethnic European Americans and African Americans.[4] The time would also be marked by labor unrest, for which certain industrialists used black people as strikebreakers, further inflaming the resentment of white workers.

The riots and killings were extensively documented by the press, which, along with the federal government, feared socialist and communist influence on the black civil rights movement of the time following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. They also feared foreign anarchists, who had bombed the homes and businesses of prominent figures and government leaders.

Background

editGreat Migration

editWith the mobilization of troops for World War I, and with immigration from Europe cut off, the industrial cities of the American Northeast and Midwest experienced severe labor shortages. As a result, northern manufacturers recruited throughout the South, from which an exodus of workers ensued.[5]

By 1919, an estimated 500,000 African Americans had emigrated from the Southern United States to the industrial cities of the Northeast and Midwest in the first wave of the Great Migration (which continued until 1940).[3] African-American workers filled new positions in expanding industries, such as the railroads, as well as many existing jobs formerly held by whites. In some cities, they were hired as strikebreakers, especially during the strikes of 1917.[5] This increased resentment against blacks among many working-class whites, immigrants, and first-generation Americans.

Racism and Red Scare

editIn the summer of 1917, violent racial riots against blacks due to labor tensions broke out in East St. Louis, Illinois, and Houston, Texas.[6] Following the war, rapid demobilization of the military without a plan for absorbing veterans into the job market, and the removal of price controls, led to unemployment and inflation that increased competition for jobs. Jobs were very difficult for African Americans to get in the South due to racism and segregation.[7]

During the First Red Scare of 1919–20, following the 1917 Russian Revolution, anti-Bolshevik sentiment in the United States quickly followed on the anti-German sentiment arising in the war years. Many politicians and government officials, together with much of the press and the public, feared an imminent attempt to overthrow the U.S. government to create a new regime modeled on that of the Soviets. Authorities viewed with alarm African-Americans' advocacy of racial equality, labor rights, and the rights of victims of mobs to defend themselves.[4] In a private conversation in March 1919, President Woodrow Wilson said that "the American Negro returning from abroad would be our greatest medium in conveying Bolshevism to America."[8] Other whites expressed a wide range of opinions, some anticipating unsettled times and others seeing no signs of tension.[9]

Early in 1919, Dr. George Edmund Haynes, an educator employed as director of Negro Economics for the U.S. Department of Labor, wrote: "The return of the Negro soldier to civil life is one of the most delicate and difficult questions confronting the Nation, north and south."[10] One black veteran wrote a letter to the editor of the Chicago Daily News saying the returning black veterans "are now new men and world men…and their possibilities for direction, guidance, honest use, and power are limitless, only they must be instructed and led. They have awakened, but they have not yet the complete conception of what they have awakened to."[11] W. E. B. Du Bois, an official of the NAACP and editor of its monthly magazine, saw an opportunity:[12]

By the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.

Events

editIn the autumn of 1919, following the violence-filled summer, George Edmund Haynes reported on the events as a prelude to an investigation by the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary. He identified 38 separate racial riots against blacks in widely scattered cities, in which whites attacked black people.[3] Unlike earlier racial riots against blacks in U.S. history, the 1919 events were among the first in which black people in number resisted white attacks and fought back.[13] A. Philip Randolph, a civil rights activist and leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, publicly defended the right of black people to self-defense.[1]

In addition, Haynes reported that between January 1 and September 14, 1919, white mobs lynched at least 43 African Americans, with 16 hanged and others shot; and another 8 men were burned at the stake. The states were unwilling to interfere or prosecute such mob murders.[3] In May, following the first serious racial incidents, W. E. B. Du Bois published his essay "Returning Soldiers":[14]

We return from the slavery of uniform which the world's madness demanded us to don to the freedom of civil garb. We stand again to look America squarely in the face and call a spade a spade. We sing: This country of ours, despite all its better souls have done and dreamed, is yet a shameful land.…

We return.

We return from fighting.

We return fighting.

Early riots: April 13–July 14

editThe National Association for the Advancement of Colored People respectfully enquires how long the Federal Government under your administration intends to tolerate anarchy in the United States?

— NAACP telegram to President Woodrow Wilson

August 29, 1919

- April 13: In rural Georgia, the riot of Jenkins County led to 6 deaths, and the destruction of various property by arson, including the Carswell Grove Baptist Church, and 3 black Masonic lodges in Millen, Georgia.

- May 10: The Charleston riot resulted in the injury of 5 white and 18 black men, along with the death of 3 others: Isaac Doctor, William Brown, and James Talbot, all black. Following the riot, the city of Charleston, South Carolina, imposed martial law.[3] A Naval investigation found that four U.S. sailors and one civilian—all white men—initiated the riot.[15]

- Early July: A white race riot in Longview, Texas, led to the deaths of at least 4 men and destroyed the African-American housing district in the town.[3]

- July 3: Local police in Bisbee, Arizona, attacked the 10th U.S. Cavalry, an African-American unit known as the "Buffalo Soldiers" formed in 1866.[16]

- July 14: The Garfield Park riot took place in Garfield Park, Indianapolis, where multiple people, including a 7-year-old girl, were wounded when gunfire broke out.

Washington and Norfolk: July 19–23

editBeginning on July 19, Washington, D.C., had four days of mob violence against black individuals and businesses perpetrated by white men—many of them in the military and in uniforms of all three services—in response to the rumored arrest of a black man for rape of a white woman. The men rioted, randomly beat black people on the street, and pulled others off streetcars for attacks.

When police refused to intervene, the black population fought back. The city closed saloons and theaters to discourage assemblies. Meanwhile, the four white-owned local papers, including the Washington Post, "ginned up...weeks of hysteria",[17] fanning the violence with incendiary headlines, calling in at least one instance for a mobilization of a "clean-up" operation.[18] After four days of police inaction, President Woodrow Wilson mobilized the National Guard to restore order.[19] When the violence ended, a total of 15 people had died: 10 white people, including two police officers; and 5 black people. Fifty people were seriously wounded, and another 100 less severely wounded. It is one of the few times in 20th-century white-on-black riots that white fatalities outnumbered those of black people.[20]

The NAACP sent a telegram of protest to President Woodrow Wilson:[21]

[T]he shame put upon the country by the mobs, including United States soldiers, sailors, and marines, which have assaulted innocent and unoffending negroes in the national capital. Men in uniform have attacked negroes on the streets and pulled them from streetcars to beat them. Crowds are reported ...to have directed attacks against any passing negro.… The effect of such riots in the national capital upon race antagonism will be to increase bitterness and danger of outbreaks elsewhere. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People calls upon you as President and Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces of the nation to make statement condemning mob violence and to enforce such military law as situation demands.…

On July 21, in Norfolk, Virginia, a white mob attacked a homecoming celebration for African-American veterans of World War I. At least 6 people were shot, and the local police called in Marines and Navy personnel to restore order.[3]

Chicago riots: July 27–August 12

editBeginning on July 27, the Chicago race riot marked the greatest massacre of Red Summer. Chicago's beaches along Lake Michigan were segregated by custom. When Eugene Williams, a black youth, swam into an area on the South Side customarily used by whites, he was stoned and drowned. Chicago police refused to take action against the attackers, and young black men responded with violence, which lasted for 13 days, with the white mobs led by the ethnic Irish.

White mobs destroyed hundreds of mostly black homes and businesses on the South Side of Chicago. The State of Illinois called in a militia force of 7 regiments: several thousand men, to restore order.[3] The riots resulted in casualties that included: 38 fatalities (23 blacks and 15 whites); 527 injured; and 1,000 black families left homeless.[22] Other accounts reported 50 people were killed, with unofficial numbers and rumors reporting even more. Labor activist William Z. Foster, among other observers, referred to the killings as "an anti-Negro pogrom" and pointed out the connections between this pogrom and the pogroms which were taking place in the former Russian empire against Jewish communities by anti-communist forces.[23]

Mid to late August

editOn August 12, at its annual convention, the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs (NFCWC) denounced the rioting and burning of Negroes' homes, asking President Wilson "to use every means within your power to stop the rioting in Chicago and the propaganda used to incite such."[24]

At the end of August, the NAACP protested again to the White House, noting the attack on the organization's secretary in Austin, Texas, the previous week. Their telegram read: "The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People respectfully enquires how long the Federal Government under your administration intends to tolerate anarchy in the United States?"[25]

The Knoxville Riot in Tennessee started on August 30–31 after the arrest of a black suspect on suspicion of murdering a white woman. Searching for the prisoner, a lynch mob stormed the county jail, where they liberated 16 white prisoners, including suspected murderers.[3] The mob attacked the African-American business district, where they fought against the district's black business owners, leaving at least 7 dead and more than 20 wounded.[26][27][28]

Omaha: September 28–29

editFrom September 28–29, the race riot of Omaha, Nebraska, erupted after a mob of over 10,000 ethnic whites from South Omaha attacked and burned the county courthouse to force the release of a black prisoner accused of raping a white woman. The mob lynched the suspect, Will Brown, hanging him and burning his body. The group then spread out, attacking black neighborhoods and stores on the north side, destroying property valued at more than a million dollars.

Once the mayor and governor appealed for help, the federal government sent U.S. Army troops from nearby forts, who were commanded by Major General Leonard Wood, a friend of Theodore Roosevelt, and a leading candidate for the Republican nomination for president in 1920.[30]

Elaine massacre and Wilmington: September 30–November

editOn September 30, a massacre occurred against blacks in Elaine, Phillips County, Arkansas,[4] being distinct for having occurred in the rural South rather than a city.

The event erupted from the resistance of the white minority against the organization of labor by black sharecroppers, along with the fear of socialism. Planters opposed such efforts to organize and thus tried to disrupt their meetings in the local chapter of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America. In a confrontation, a white man was fatally shot and another wounded. The planters formed a militia to arrest the African-American farmers, and hundreds of whites came from the region. They acted as a mob, attacking black people over two days at random. During the riot, the mob killed an estimated 100 to 237 black people, while 5 whites also died in the violence.

Arkansas Governor Charles Hillman Brough appointed a Committee of Seven, composed of prominent local white businessmen, to investigate. The committee would conclude that the Sharecroppers' Union was a Socialist enterprise and "established for the purpose of banding negroes together for the killing of white people."[31] The report generated such headlines as the following in the Dallas Morning News: "Negroes Seized in Arkansas Riots Confess to Widespread Plot; Planned Massacre of Whites Today." Several agents of the Justice Department's Bureau of Investigation spent a week interviewing participants, though speaking to no sharecroppers. The Bureau also reviewed documents, filing a total of nine reports stating there was no evidence of a conspiracy of the sharecroppers to murder anyone.

The local government tried 79 black people, who were all convicted by all-white juries, and 12 were sentenced to death for murder. As Arkansas and other southern states had disenfranchised most black people at the turn of the 20th century, they could not vote, run for political office, or serve on juries. The remainder of the defendants were sentenced to prison terms of up to 21 years. Appeals of the convictions of 6 of the defendants went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reversed the verdicts due to failure of the court to provide due process. This was a precedent for heightened Federal oversight of defendants' rights in the conduct of state criminal cases.[32]

On November 13, the Wilmington race riot was violence between white and black residents of Wilmington, Delaware.

Other events

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

A white woman named Ruth Meeks accused a black man named John Hartfield of attacking and raping her on June 9, 1919, in Ellisville, Mississippi. Mobs hunted down Hartfield as he ran for his life, but the mobs eventually shot and captured Hartfield on June 24 as he tried to board a train. He was held in jail, but mobs eventually came back and took him away, as the sheriff allowed them to. The mob had a doctor treat Hartfield for his gunshot wound, so the mob could organize his death in a way they saw fit. On June 26, 1919, the mob took Hartfield to a field in Ellisville, Mississippi, cut off his fingers, hung him from a tree branch, shot him over 2,000 times, and when the rope was severed and Hartfield fell from the tree, the mob burned his body. 10,000 whites came to the field to see Hartfield’s murder. Vendors sold trinkets and photographs. Newspapers reported that a resentful Hartfield’s last words were a warning for all men to think before they do wrong. This statement from the papers seems highly unlikely due to the state of Hartfield’s injuries and his attempt to run away for over a week before the mob got him.

On September 8, 1919, a mob of white men lynched Bowman Cook and John Morine.[33] During August of 1919 in Jacksonville, Florida, several black taxi drivers were killed by white passengers. Black taxi drivers began to refuse service to white riders. When one white rider was denied service, he fired into a crowd of black people, killing one man. Police wrongly blamed Cook and Morine for the man’s death. Three weeks later, a mob broke into the jail where the men were being held and captured them.[34] The mob drove them to a desolate area of town and shot them, then they tied Cook’s body to a car and drove it for 50 blocks. The dragging drew attention to the spectacle and mutilated his corpse.

On October 4, there was a union strike at Gary’s U.S. Steel mill in Gary, Indiana. This strike was held by the white labor population of the mill as the union could not recruit the black workers’ support. To break this strike, U.S. Steel hired almost a thousand local and non-local black strikebreakers. These strikebreakers were shipped into Gary for their safety and they were provided cots, entertainment, and overtime pay. At the same time, U.S. Steel turned to theatrics and attempted to agitate the white strikers. They did this by first emasculating white strikers then later by paying unrelated black residents of Gary to march in a parade towards the steel mill. On October 4, 1919, hundreds of striking workers assaulted a stalled street car bearing 40 black strikebreakers. At first the mob resorted to heckling, then the throwing of rocks, and eventually, the mob dragged the strikebreakers from their streetcar and beat them, dragging them through the streets. The hysteria led to an eight block mob leaving many unconscious in its wake leading to the state militia and federal troops stepping in to intervene.[35] Martial law was enacted and many historians[example needed] agree that it was the Riot of 1919 that broke the unions in Gary.[citation needed]

Chronology

editThis list is primarily, but not exclusively, based on George Edmund Haynes's report, as summarized in the New York Times (1919).[3]

| Date | Place |

|---|---|

| January 22[a] | Bedford County, Tennessee |

| February 8 | Blakeley, Georgia[a][b] |

| March 12 | Pace, Florida |

| March 14 | Memphis, Tennessee[a][c] |

| April 10 | Morgan County, West Virginia |

| April 13 | Jenkins County, Georgia |

| April 14 | Sylvester, Georgia |

| April 15 | Millen, Georgia[d] |

| May 5 | Pickens, Mississippi |

| May 10 | Charleston, South Carolina |

| May 10 | Sylvester, Georgia[a][e] |

| May 21 | El Dorado, Arkansas |

| May 26 | Milan, Georgia |

| May 29 | New London, Connecticut |

| May 27–29 | Putnam County, Georgia |

| May 31 | Monticello, Mississippi[a] |

| June 6 | New Brunswick, New Jersey[a] |

| June 13 | Memphis, Tennessee[a] |

| June 13 | New London, Connecticut[f] |

| June 26 | Ellisville, Mississippi[a] |

| June 27 | Annapolis, Maryland[g] |

| June 27 | Macon, Mississippi |

| July 3 | Bisbee, Arizona |

| July 5 | Scranton, Pennsylvania[h] |

| July 6 | Dublin, Georgia |

| July 7 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| July 8 | Coatesville, Pennsylvania |

| July 9 | Tuscaloosa, Alabama[a][i] |

| July 10–12 | Longview, Texas[39] |

| July 11 | Baltimore, Maryland |

| July 15 | Louise, Mississippi |

| July 15 | Port Arthur, Texas |

| July 19–24 | Washington, D.C. |

| July 20 | New York City, New York |

| July 21 | Norfolk, Virginia |

| July 23 | New Orleans, Louisiana[a] |

| July 23 | Darby, Pennsylvania |

| July 26 | Hobson City, Alabama[j] |

| July 27 – August 3 | Chicago, Illinois |

| July 28 | Newberry, South Carolina[k] |

| July 31 | Bloomington, Illinois[a] |

| July 31 | Syracuse, New York |

| July 31 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| August 1 | Whatley, Alabama |

| August 3 | Lincoln, Arkansas |

| August 4 | Hattiesburg, Mississippi[a] |

| August 6 | Texarkana, Texas[40] |

| August 21 | New York City, New York |

| August 22 | Austin, Texas |

| August 27–29 | Ocmulgee, Georgia |

| August 30 | Knoxville, Tennessee |

| August 31 | Bogalusa, Louisiana |

| September 8 | Jacksonville, Florida[a] |

| September 10 | Clarksdale, Mississippi |

| September 28–29 | Omaha, Nebraska |

| September 29 | Montgomery, Alabama |

| October 1–2 | Elaine, Arkansas |

| October 1–2 | Baltimore, Maryland |

| October 4 | Gary, Indiana[a] |

| October 31 | Corbin, Kentucky |

| November 2 | Macon, Georgia |

| November 11 | Magnolia, Arkansas |

| November 13 | Wilmington, Delaware |

| December 27 | West Virginia |

Responses

editWe appeal to you to have your country undertake for its racial minority that which you forced Poland and Austria to undertake for their racial minorities.

— National Equal Rights League to President Woodrow Wilson, November 25, 1919

In September 1919, in response to the Red Summer, the African Blood Brotherhood formed in northern cities to serve as an "armed resistance" movement. Protests and appeals to the federal government continued for weeks. A letter from the National Equal Rights League, dated November 25, appealed to Wilson's international advocacy for human rights: "We appeal to you to have your country undertake for its racial minority that which you forced Poland and Austria to undertake for their racial minorities."[41]

Haynes's report

editThe October 1919 report by Dr. George Edmund Haynes is a call to national action, and was published in The New York Times and other major newspapers.[3] Haynes noted that lynchings were a national problem. As President Wilson had noted in a 1918 speech: from 1889 to 1918, more than 3,000 people had been lynched; 2,472 were black men, and 50 were black women. Haynes said that states had shown themselves "unable or unwilling" to put a stop to lynchings, and seldom prosecuted the murderers. The fact that white men had also been lynched in the North, he argued, demonstrated the national nature of the overall problem: "It is idle to suppose that murder can be confined to one section of the country or to one race."[3] He connected the lynchings to the widespread racial riots against blacks in 1919:[3]

Persistence of unpunished lynchings of negroes fosters lawlessness among white men imbued with the mob spirit and creates a spirit of bitterness among negroes. In such a state of public mind, a trivial incident can precipitate a riot.

Disregard of law and legal process will inevitably lead to more and more frequent clashes and bloody encounters between white men and negroes and a condition of potential race war in many cities of the United States.

Unchecked mob violence creates hatred and intolerance, making impossible free and dispassionate discussion not only of race problems, but questions on which races and sections differ.

Lusk Committee

editThe Joint Legislative Committee to Investigate Seditious Activities, popularly known as the Lusk Committee, was formed in 1919 by the New York State Legislature to investigate individuals and organizations in New York State suspected of sedition. The committee was chaired by freshman State Senator Clayton R. Lusk of Cortland County, who had a background in business and conservative political values, referring to radicals as "alien enemies."[42] Only 10% of the four-volume work constituted a report, while the rest reprinted materials seized in raids or supplied by witnesses, much of it detailing European activities, or surveyed efforts to counteract radicalism in every state, including citizenship programs and other patriotic educational activities. Other raids targeted the left-wing of the Socialist Party and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). When they analyzed the materials it hauled away, it made much of attempts to organize "American Negroes" and calls for revolutions in foreign-language magazines.[43][44]

Press coverage

editIn mid-summer, in the middle of the Chicago racial violence against blacks, a federal official told The New York Times that the violence resulted from "an agitation, which involves the I.W.W., Bolshevism and the worst features of other extreme radical movements."[45] He supported that claim with copies of Negro publications that called for alliances with leftist groups, praised the Soviet regime, and contrasted the courage of jailed socialist Eugene V. Debs with the "school boy rhetoric" of traditional black leaders. The Times characterized the publications as "vicious and apparently well financed," mentioned "certain factions of the radical Socialist elements," and reported it all under the headline: "Reds Try to Stir Negroes to Revolt".[45] In late 1919, Oklahoma's Daily Ardmoreite published a piece with a headline describing "Evidence Found Of Negro Society That Brought On Rioting".[46]

In response, some black leaders such as Bishop Charles Henry Phillips of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church asked black people to shun violence in favor of "patience" and "moral suasion." Phillips opposed propaganda favoring violence, and he noted the grounds of injustice to the black people:[47] Phillips was based in Nashville, Tennessee.

I cannot believe that the negro was influenced by Bolshevist agents in the part he took in the rioting. It is not like him to be a traitor or a revolutionist who would destroy the Government. But then the reign of mob law to which he has so long lived in terror and the injustices to which he has had to submit have made him sensitive and impatient.

The connection between black people and Bolshevism was widely repeated. In August 1919, The Wall Street Journal wrote: "Race riots seem to have for their genesis a Bolshevist, a Negro, and a gun." The National Security League repeated that reading of events.[48] In presenting the Haynes report in early October, The New York Times provided a context which his report did not mention. Haynes documented violence and inaction on the state level.

The Times saw "bloodshed on a scale amounting to local insurrection" as evidence of "a new negro problem" because of "influences that are now working to drive a wedge of bitterness and hatred between the two races."[3] Until recently, the Times said, black leaders showed "a sense of appreciation" for what whites had suffered on their behalf in fighting a civil war that "bestowed on the black man opportunities far in advance of those he had in any other part of the white man's world".[3] Now militants were supplanting Booker T. Washington, who had "steadily argued conciliatory methods." The Times continued:[3]

Every week the militant leaders gain more headway. They may be divided into general classes. One consists of radicals and revolutionaries. They are spreading Bolshevist propaganda. It is reported that they are winning many recruits among the colored race. When the ignorance that exists among negroes in many sections of the country is taken into consideration the danger of inflaming them by revolutionary doctrine may [be] apprehended.... The other class of militant leaders confine their agitation to a fight against all forms of color discrimination. They are for a program on uncompromising protest, "to fight and continue to fight for citizenship rights and full democratic privileges."

As evidence of militancy and Bolshevism, the Times named W. E. B. Du Bois and quoted his editorial in The Crisis, which he edited:[3]

Today we raise the terrible weapon of self-defense ... When the armed lynchers gather, we too must gather armed." When the Times endorsed Haynes' call for a bi-racial conference to establish "some plan to guarantee greater protection, justice, and opportunity to Negroes that will gain the support of law-abiding citizens of both races", it endorsed discussion with "those negro leaders who are opposed to militant methods.

In mid-October government sources provided the Times with evidence of Bolshevist propaganda appealing to America's black communities. This account set Red propaganda in the black community into a broader context, since it was "paralleling the agitation that is being carried on in industrial centres of the North and West, where there are many alien laborers".[49] The Times described newspapers, magazines, and "so-called 'negro betterment' organizations" as the way propaganda about the "doctrines of Lenin and Trotzky" was distributed to black people.[49] It cited quotes from such publications, which contrasted the recent violence in Chicago and Washington, D.C., with:[49]

...Soviet Russia, a country in which dozens of racial and lingual types have settled their many differences and found a common meeting ground, a country which no longer oppresses colonies, a country from which the lynch rope is banished and in which racial tolerance and peace now exist.

The Times noted a call for unionization: "Negroes must form cotton workers' unions. Southern white capitalists know that the negroes can bring the white bourbon South to its knees. So go to it."[49] Coverage of the root causes of the riot against black people in Elaine, Arkansas evolved as the violence stretched over several days. A dispatch from Helena, Arkansas, to the New York Times datelined October 1 said: "Returning members of the [white] posse brought numerous stories and rumors, through all of which ran the belief that the rioting was due to propaganda distributed among the negroes by white men."[50] The next day's report added detail: "Additional evidence has been obtained of the activities of propagandists among the negroes, and it is thought that a plot existed for a general uprising against the whites." A white man had been arrested and was "alleged to have been preaching social equality among the negroes". Part of the headline was: "Trouble Traced to Socialist Agitators".[51] A few days later a Western Newspaper Union dispatch captioned a photo using the words "Captive Negro Insurrectionists."[52]

Government activity

editDuring the Chicago racial violence against people of color the press was incorrectly told by Department of Justice officials that the IWW, socialists, and Bolsheviks were "spreading propaganda to breed race hatred".[53] FBI agents filed reports that leftist views were winning converts in the black community. One cited the work of the NAACP "urging the colored people to insist upon equality with white people and to resort to force, if necessary.[48] J. Edgar Hoover, at the start of his career in government, analyzed the riots for the Attorney General. He blamed the July Washington, D.C., riots on "numerous assaults committed by Negroes upon white women".[20] For the October events in Arkansas, he blamed "certain local agitation in a Negro lodge".[20] A more general cause he cited was "propaganda of a radical nature".[20] He charged that socialists were feeding propaganda to black-owned magazines such as The Messenger, which in turn aroused their black readers. He did not note the white perpetrators of violence, whose activities local authorities documented. As chief of the Radical Division within the U.S. Department of Justice, Hoover began an investigation of "negro activities" and targeted Marcus Garvey because he thought his newspaper Negro World preached Bolshevism.[20] He authorized the hiring of black undercover agents to spy on black organizations and publications in Harlem.[53]

On November 17, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer reported to Congress on the threat that anarchists and Bolsheviks posed to the government. More than half the report documented radicalism in the black community and the "open defiance" black leaders advocated in response to racial violence and the summer's rioting. It faulted the leadership of the black community for an "ill-governed reaction toward race rioting.… In all discussions of the recent racial riots against blacks there is reflected the note of pride that the Negro has found himself. That he has 'fought back,' that never again will he tamely submit to violence and intimidation."[54] It described "the dangerous spirit of defiance and vengeance at work among the Negro leaders."[54]

Arts

editClaude McKay's sonnet, "If We Must Die",[55] was prompted by the events of Red Summer.[56]

See also

edit- African-American veterans lynched after World War I

- African Blood Brotherhood

- Black genocide – the notion that African Americans have been subjected to genocide

- Buffalo supermarket shooting

- Charleston Church shooting

- Freedmen massacres

- King assassination riots

- List of ethnic riots § United States

- List of expulsions of African Americans

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- List of massacres in the United States

- Lynching in the United States

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- Racial Equality Proposal

- Racism against African Americans

- Racism in the United States

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n One of the only records of this riot is a New York Times article. Newspapers across the country report that a "race riot" was "narrowly averted" in New Orleans on July 22. "Race Riots in New Orleans and Washington", Brewton Standard, July 24, 1919, 1; "Louisiana," Bossier Banner-Progress, July 24, 1919, 1' "Race Riot Narrowly Averted in New Orleans," Phenix-Gerard Journal, July 24, 1919, 1; "Race Clash Narrowly Averted at New Orleans," Emancipator, July 26, 1919, 1.[3]

- ^ New York Times show that 4 people were killed.[3]

- ^ New York Times show that 1 person was killed in Memphis, Tennessee[3]

- ^ Misspelling of Millen, Georgia. Riot was part of the Jenkins County, Georgia, riot of 1919

- ^ New York Times show that 1 person was killed.[3]

- ^ Records show that during New London, Connecticut, riot several people were injured[36][37]

- ^ Atypical in that the violence was primarily between civilian African Americans and African American sailors but also included instances of white sailors attacking civilian African Americans.

- ^ "'Negroes Accused of Inciting Riot,' Philadelphia Inquirer, July 10, 1919. The NAACP later reported to Conggress and the New York Times that a race riot erupted on July 5 in Scranton, Pennsylvania. However, no evidence of such an incident exists."[38]

- ^ Records show that during Tuscaloosa riot 1 person was injured[36][37]

- ^ Records show that during Hobson City riot one person was injured[36][37]

- ^ The Newberry 1919 lynching attempt happened on July 24

References

edit- ^ a b Erickson, Alana J. 1960. "Red Summer." Pp. 2293–94 in Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. New York: Macmillan.

- ^ Cunningham, George P. 1960. "James Weldon Johnson." Pp. 1459–61 in Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. New York: Macmillan.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u The New York Times 1919.

- ^ a b c Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) 2018, p. Part 3.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, pp. 279, 281–282.

- ^ Barnes 2008, p. 4.

- ^ "The Great Migration". December 15, 2023.

- ^ McWhirter 2011, p. 56

- ^ McWhirter 2011, pp. 19, 22–24

- ^ McWhirter 2011, p. 13

- ^ McWhirter 2011, p. 15

- ^ McWhirter 2011, p. 14

- ^ Maxouris 2019.

- ^ McWhirter 2011, pp. 31–32, emphasis in original

- ^ Rucker & Upton 2007, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Rucker & Upton 2007, p. 554.

- ^ Brockell, Gillian (July 15, 2019). "The deadly race riot 'aided and abetted' by The Washington Post a century ago". Washington Post.

- ^ Perl 1999, p. A1

- ^ Mills 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Ackerman 2008, pp. 60–62.

- ^ The New York Times 1919h.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 2019.

- ^ William Z. Foster (1952). History of the Communist Party of the United States. p. 231.

- ^ The New York Times 1919j.

- ^ The New York Times 1919i.

- ^ Wheeler 2017.

- ^ Whitaker 2009, p. 53.

- ^ Lakin 2000, pp. 1–29.

- ^ Lewis 2009, p. 383.

- ^ Pietrusza 2009, pp. 167–172.

- ^ Freedman 2001, p. 68.

- ^ Whitaker 2009, pp. 131–142.

- ^ Urell, Aaryn (October 17, 2021). "Historical Marker Dedicated for Veterans Lynched in Jacksonville, Florida". Equal Justice Initiative. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ Cassanello, Robert (2003). "Violence, Racial Etiquette, and African American Working-Class Infrapolitics in Jacksonville during World War I" (PDF). The Florida Historical Quarterly. 82 (2): 164–165 – via UCF Digital Collections.

- ^ "Why the Great Steel Strike of 1919 Was One of Labor's Biggest Failures". HISTORY. September 23, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c United States House Committee on the Judiciary 1920, p. 9

- ^ a b c United States House Committee on the Judiciary 1920a, p. 19

- ^ McWhirter 2011, p. 291.

- ^ Whitaker 2009, p. 51.

- ^ Marcelle 2016.

- ^ The New York Times 1919e.

- ^ Jaffe 1972, pp. 121–122.

- ^ New-York Tribune 1919, p. 1.

- ^ Brown, Smith & Johnson 1922, p. 313.

- ^ a b The New York Times 1919c.

- ^ The Daily Ardmoreite 1919, p. 1.

- ^ The New York Times 1919d.

- ^ a b McWhirter 2011, p. 160

- ^ a b c d The New York Times 1919a.

- ^ The New York Times 1919b.

- ^ The New York Times 1919f.

- ^ The New York Times 1919g.

- ^ a b McWhirter 2011, p. 159

- ^ a b McWhirter 2011, pp. 239–241

- ^ "If We Must Die" poetryfoundation.org, accessed May 5, 2015

- ^ McKay 2007.

Bibliography

edit- Ackerman, Kenneth D. (2008). Young J. Edgar: Hoover, the Red Scare, and the Assault on Civil Liberties. Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 9780306816277. - Total pages: 472

- The Daily Ardmoreite (October 5, 1919). "Evidence Found Of Negro Society That Brought On Rioting". The Daily Ardmoreite. Ardmore, Carter, Oklahoma: John F. Easley. pp. 1–20. ISSN 1065-7894. OCLC 12101538. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- Barnes, Harper (2008). Never Been a Time: The 1917 Race Riot That Sparked the Civil Rights Movement. New York: Walker & Co. ISBN 9780802715753. - Total pages: 304

- Brown, Roscoe C. E.; Smith, Ray B.; Johnson, Willis F.; et al. (1922). History of the State of New York: Political and Government: Vol. 4: 1896–1920. Syracuse Press.

- Dray, Philip, At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America (NY: Random House, 2002)

- "Chicago Race Riot of 1919". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- Freedman, Eric M. (2001). Habeas Corpus: Rethinking the Great Writ of Liberty. New York University Press. ISBN 9780814727171. - Total pages: 243

- Jaffe, Julian F. (1972). Crusade Against Radicalism: New York During the Red Scare, 1914-1924. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press. ISBN 9780804690263. - Total pages: 265

- Kennedy, David M. (2004). Over Here: The First World War and American Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195174007. - Total pages: 428

- Krist, Gary. City of Scoundrels: The Twelve Days of Disaster That Gave Birth to Modern Chicago. New York, NY: Crown Publisher, 2012. ISBN 978-0-307-45429-4.

- Lakin, Matthew (2000). "'A Dark Night': The Knoxville Race Riot of 1919". Journal of East Tennessee History. 72. East Tennessee Historical Society. ISSN 1058-2126. OCLC 23044540.

- Lewis, David Levering (2009). W. E. B. Du Bois: A Biography. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9781466843073. - Total pages: 912

- Marcelle, Dale (2016). Pitchforks and Negro Babies: America's Shocking History of Hate. AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781524625764. - Total pages: 328

- McKay, Claude (2007) [New York Arno:1937]. A Long Way from Home. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813539683. - Total pages: 270

- McWhirter, Cameron (2011). Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9780805089066. - Total pages: 368

- Mills, Darhian (April 2, 2016). "Washington, DC Race Riot (1919)". BlackPast. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- Maxouris, Christina (July 27, 2019). "100 years ago, white mobs across the country attacked black people. And they fought back". CNN. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- New-York Tribune (July 17, 1919). "Reds Work in the South". New-York Tribune. New York. pp. 1–20. ISSN 1941-0646. OCLC 9405688. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- The New York Times (July 22, 1919h). "Protest Sent to Wilson". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- The New York Times (July 28, 1919c). "Reds Try to Stir Negroes to Revolt". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- The New York Times (August 1, 1919j). "Negroes Appeal to Wilson" (PDF). The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- The New York Times (August 3, 1919d). "Denies Negroes are 'Reds'". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- The New York Times (August 30, 1919i). "Negro Protest to Wilson". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- The New York Times (October 5, 1919). "For Action on Race Riot Peril". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- The New York Times (October 2, 1919b). "None Killed in Fight with Arkansas Posse". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- The New York Times (October 3, 1919f). "Six More are Killed in Arkansas Riots". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- The New York Times (October 12, 1919g). "Article 34 -- No Title". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- The New York Times (October 19, 1919a). "Reds are Working among Negroes". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- The New York Times (November 26, 1919e). "Ask Wilson to Aid Negroes". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- Onion, Rebecca (March 4, 2015). "Red Summer". Slate.

- Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) (July 3, 2018). "The Great War: A Nation Comes of Age – Part 3, Transcript". Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- Perl, Peter (March 1, 1999). "Race Riot of 1919 Gave Glimpse of Future Struggles". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- Pietrusza, David (2009). 1920: The Year of the Six Presidents. Basic Books. ISBN 9780786732135. - Total pages: 240

- Rucker, Walter C.; Upton, James N. (2007). Encyclopedia of American Race Riots, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313333026. - Total pages: 930

- Tuttle, William M., Jr., Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996), originally published 1970

- United States House Committee on the Judiciary (1920). Segregation and Antilynching: Hearings Before the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, Sixty-six Congress, 2d Session on H.J. Res. 75; H.R. 259, 4123, and 11873. Serial No. 14. Federal government of the United States. - Total pages: 65

- United States House Committee on the Judiciary (1920a). Hearings Before the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, Sixty-sixth Congress, First[-third] Session: Segregation. Anti-lynching. United States Government Publishing Office.

- Wheeler, W Bruce (October 8, 2017). "Knoxville Riot of 1919". Tennessee Historical Society. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- Whitaker, Robert (2009). On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice That Remade a Nation. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 9780307339836. - Total pages: 386