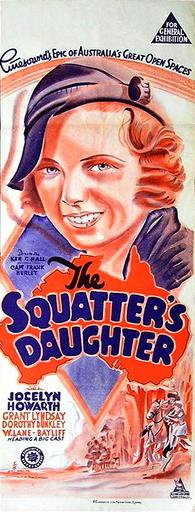

The Squatter's Daughter is a 1933 Australian melodrama directed by Ken G. Hall and starring Jocelyn Howarth. One of the most popular Australian films of the 1930s, it is based on a 1907 play by Bert Bailey and Edmund Duggan which had been previously adapted to the screen in 1910.

| The Squatter's Daughter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Ken G. Hall |

| Written by | Gayne Dexter E. V. Timms |

| Based on | play by Bert Bailey & Edmund Duggan |

| Produced by | Ken G. Hall |

| Starring | Jocelyn Howarth Grant Lyndsay |

| Cinematography | Frank Hurley George Malcolm |

| Edited by | George Malcolm William Shepherd |

| Music by | Frank Chapple Tom King |

Production company | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 104 mins (Australia) 90 mins (England) |

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £16,000[1][2] or £11,000[3][4] |

| Box office | £35,000[5][6] or £28,000[7] £7,500 (UK)[8] |

It has been described as "part of an Australian subgenre, the outdoors colonial melodrama... stories set on outback stations featuring unscrupulous farmers, heroic foremen, upper class twits visiting from England, family secrets and feisty horse-riding heroines. The latter formed the "squatter’s daughter" archetype – the brave, beautiful farm girl who galloped away from bushfires – and meant female starring roles were often stronger in Australian rather than American westerns. "[9]

Plot

editJoan Enderby runs her family sheep station but is about to lose it because she can't afford to buy the lease from the Sherringtons, who run the neighbouring station, Waratah. While Ironbark Sherrington has been away in London looking for a cure to save his sight, his son Clive and overseer, Fletcher have planned to bankrupt Enderby station. Joan is helped by a mysterious newcomer, Wayne Ridgeway, who is actually the rightful heir to the Sherrington estate.

There is a subplot about Joan's crippled brother Jimmy, who is in love with Zena, daughter of Jebal Zim, an Afghan trader. When Zim tries to tell Ironbark that Ridgeway is the true heir, Fletcher kills him and abducts Zena. Joan and Ridgeway manage to fight a bushfire that threatens Enderby, deliver sheep, rescue Zena and capture Fletcher.

Cast

edit- Jocelyn Howarth as Joan Enderby

- Grant Lyndsay as Wayne Ridgeway

- John Warwick as Clive Sherrington

- Fred MacDonald as shearer

- W. Lane-Bayliff as Old Ironbark

- Dorothy Dunckley as Miss Ramsbottom[10]

- Owen Ainley as Jimmy

- Cathleen Esler as Zena

- George Cross

- Claude Turton as Jebal Zim

- George Lloyd as Shearer

- Les Warton

- Katie Towers as Poppy

Production

editScripting

editCinesound had originally intended to follow up their successful first feature, On Our Selection (1932) with an adaptation of The Silence of Dean Maitland. However they had difficulty finding appropriate actors to play the leads and instead decided to adapt the 1907 play The Squatter's Daughter, which had previously been filmed in 1910.[11]

By December 1932 director Ken G. Hall had hired novelist E. V. Timms to work on him with the adaptation.[12]

However Hall was not happy with the result, so he brought on his old boss, Gayne Dexter, to do a rewrite.[13] A novelisation of the script by Charles Melaun was published in 1933.[14]

Casting

editJocelyn Howarth was a discovery of director Ken G. Hall. She moved to Hollywood and had a career under the name "Constance Worth". She was paid £6 a week.[4]

Grant Lyndsay had previously played the romantic lead in On Our Selection (1932).

Filming

editShooting commenced February 1932 at Cinesound's studio in Bondi and on location at Goonoo Goonoo station near Tamworth.[15][16][17] The bushfire finale was filmed near Wallacia, west of Sydney. During this sequence, the crew placed old nitrate film amongst the trees for the fire to burn more fiercely. It resulted in extra high flames, although Grant Lyndsay hurt his hand diving into a pool, and Ken Hall and Frank Hurley were singed.[18] Jocelyn Howarth was also injured during the making of the movie.[19]

Filming was scheduled to take ten weeks but because of poor weather it ended up taking eighteen.[20] There was additional filming on board a ship a number of months later.[21]

Reception

editAustralian reviews were generally positive and the movie was successful at the box office.[22] By the end of 1934 it had earned an estimated profit of £5,900[3][4] and by the end of 1935 it had grossed over £25,000 in Australia and New Zealand.[1]

UK distribution rights were bought by MGM for £7,500; the film was released there under the title Down Under.[23]

In 1952 Hall estimated the film had earned just under £50,000.[24]

References

edit- ^ a b Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900–1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1998, 162.

- ^ Pike, Andrew Franklin. "The History of an Australian Film Production Company: Cinesound, 1932-70" (PDF). Australian National University. p. 245.

- ^ a b "Counting the CASH in Australian Films. "Selection Nets Rert Bailey £14,000 What Others Cost and Lost—Stars' Salaries and Story Prices.", Everyones., Sydney: Everyones Ltd, 12 December 1934, nla.obj-577835346, retrieved 15 August 2024 – via Trove

- ^ a b c "Film Industry in Australia". The News. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 11 June 1935. p. 4. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ The Home : an Australian quarterly, Art in Australia, 1920, retrieved 29 March 2019

- ^ Graham Shirley and Brian Adams, Australian Cinema: The First Eighty Years, Currency Press, 1998, 119.

- ^ l-category = Article%7Ccategory%3AArticle 'SOME SCREEN REFLECTIONS ADDING UP THE COSTS Films Make Money Fly', The Courier-Mail (Brisbane), Thursday 29 February 1940 p 9

- ^ sortby = dateAsc 'CINESOUND FILMS. PLANS FOR THE FUTURE. STATEMENT BY MR. STUART DOYLE', The Sydney Morning Herald Saturday 28 July 1934 p 9

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (24 July 2019). "50 Meat Pie Westerns". Filmink.

- ^ "The- Social- Whirl- and- Personal- Pars- on- Prominent- People". Sunday Times. Perth: National Library of Australia. 3 September 1933. p. 1 Section: Second Section. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "CINESOUND LTD". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 7 December 1932. p. 15. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "ANOTHER HIT". The Sun. No. 1550. New South Wales, Australia. 11 December 1932. p. 24. Retrieved 11 March 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Ken G. Hall, Directed by Ken G. Hall, Lansdowne Press, 1977 p 75

- ^ The Squatter's Daughter at AustLit

- ^ "NEW TALKIE STUDIO". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 20 February 1933. p. 4. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ ""TALKIE" STUDIO". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 30 March 1933. p. 9. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "BY AIR". Sunday Times. Perth: National Library of Australia. 6 August 1933. p. 9 Section: First Section. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "FILMING BUSH FIRE". The Barrier Miner. Broken Hill, NSW: National Library of Australia. 19 May 1933. p. 1. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "DANGER AND PAIN". The Worker. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 14 June 1933. p. 14. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "UNIQUE QUEENSLAND SCENERY". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 22 September 1934. p. 10. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ "MOVING PICTURE ON TOURIST STEAMER". The Advertiser. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 17 August 1933. p. 7. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "FILM RIVEWS". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 2 October 1933. p. 3. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "CINESQUND FILMS". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 28 July 1934. p. 9. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ^ "THE RESEARCH BUREAU HOLDS AN AUTOPSY". Sunday Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 17 February 1952. p. 11. Retrieved 28 April 2013.