The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was

"The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was" or "The Story of a Boy Who Went Forth to Learn Fear" (German: Märchen von einem, der auszog das Fürchten zu lernen) is a German folktale collected by the Brothers Grimm in Grimm's Fairy Tales (KHM 4).[1] The tale was also included by Andrew Lang in The Blue Fairy Book (1889).

| The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was | |

|---|---|

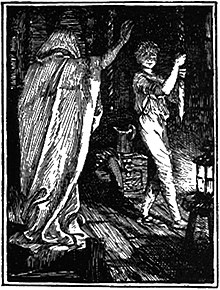

The "ghost" in the bell tower | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was |

| Also known as | Märchen von einem, der auszog das Fürchten zu lernen |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 326 |

| Country | Germany |

| Published in | Grimms' Fairy Tales, Vol. I |

It is classified as its own Aarne–Thompson index type 326. It refers to tales of a male protagonist's unsuccessful attempts to learn how to feel fear.[2]

This tale type did not appear in any early literary collection but is heavily influenced by the medieval adventure of Sir Lancelot du Lac called The Marvels of Rigomer in which he spends a night in a haunted castle and undergoes almost the same ordeals as the youth.[3]

Origin

editThe tale was published by the Brothers Grimm in the second edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen in 1819. The first edition (1812) contained a much shorter version titled "Good Bowling and Card-Playing" (German: Gut Kegel- und Kartenspiel). Their immediate source was Ferdinand Siebert from the village of Treysa near Kassel; the Brothers Grimm also knew several variants of this widespread tale.[1]

Synopsis

editA father had two sons. The dimwitted younger son, when asked by his father what he would like to learn to support himself, said he would like to learn how to shudder (as in, learn to have fear). A sexton told the father that he could teach the boy. After teaching him to ring the church bell, he sent him one midnight to ring it and came after him, dressed as a ghost. The boy demanded an explanation. When the sexton did not answer, the boy, unafraid, pushed him down the stairs, breaking his leg.

His horrified father turned him out of house, so the boy set out to learn how to shudder. He complained whenever he could, "If only I could shudder!" One man advised him to stay the night beneath the gallows, where seven hanged men were still hanging. He did so, and set a fire for the night. When the hanged bodies shook in the wind, he thought they must be cold. He cut them down and sat them close to his fire, but they did not stir even when their clothing caught on fire. The boy, annoyed at their carelessness, hung them back up in the gallows.

After the incident at the gallows, he began traveling with a waggoner. When one night they arrived at an inn, the inn-keeper told him that if he wanted to know how to shudder, he should visit the haunted castle nearby. If he could manage to stay there for three nights in a row, he could learn how to shudder, as well as win the king's daughter and all of the rich treasures of the castle. Many men had tried, but none had succeeded.

The boy accepted the challenge and went to the king. The king agreed, and told him that he may bring with him three non-living things into the castle. The boy asked for a fire, a lathe, and a cutting board with a knife.

The first night, as the boy sat in his room, two voices from the corner of the room moaned into the night, complaining about the cold. The boy, unafraid, claimed that the owners of the voices were stupid not to warm themselves with the fire. Suddenly, two black cats jumped out of the corner and, seeing the calm boy, proposed a card game. The boy tricked the cats and trapped them with the cutting board and knife. Black cats and dogs emerged from every patch of darkness in the room, and the boy fought and killed each of them with his knife. Then, from the darkness, a bed appeared. He lay down on it, preparing for sleep, but it began walking all over the castle. Still unafraid, the boy urged it to go faster. The bed turned upside down on him, but the boy, unfazed, just tossed the bed aside and slept next to the fire until morning.

As the boy settled in for his second night in the castle, half of a man fell down the chimney. The boy, again unafraid, shouted up the chimney that the other half was needed. The other half, hearing the boy, fell from the chimney and reunited with the rest. More men followed with human skulls and dead men's legs with which to play nine-pins. The amused boy shaped the skulls into better balls with his lathe and joined the men until midnight, when they vanished into thin air.

On his third and final night in the castle, the boy heard a strange noise. Six men entered his room, carrying a coffin. The boy, unafraid but distraught, believed the body to be his own dead cousin. As he tried to warm the body, it came back to life, and, confusedly, threatened to strangle him. The boy, angry at his ingratitude, closed the coffin on top of the man again. An old man hearing the noise came to see the boy. He visited with him, bragging that he could knock an anvil straight to the ground. The old man brought him to the basement and, while showing the boy his trick, the boy split the anvil and trapped the old man's beard in it, and then proceeded to beat the man with an iron rod. The man, desperate for mercy, showed the boy all of the treasures in the castle.

The following morning, the king told the boy that he could win his lovely daughter. The boy agreed, though upset that he had still not learned how to shudder.

After their wedding, the boy's continuing complaints "If only I could shudder!" annoyed his wife to no end. Reaching her wits' end, she sent for a bucketful of stream water, complete with gudgeons. She tossed the freezing water onto her husband while he was asleep. As he awoke, shuddering, he exclaimed that while he had finally learned to shudder, he still did not know what true fear was.[1]

History

editThe fairy tale is based on a tale from the German state of Mecklenburg and one from Zwehrn in Hesse, probably from Dorothea Viehmann,[4] as told by Ferdinand Siebert from the area of the Schwalm. In the first edition of "Gut Kegel- und Kartenspiel" (translated "Good Bowling and Card Playing") from 1812, the story is limited to the castle and begins with the king's offer to win his daughter when she turned 14. The hero is not a fool but merely a bold young man who, being very poor, wishes to try it.[5] The full story was only published in the journal "Wünschelruthe Nr. 4" in 1818, and one year later in the "Kinder- und Hausmärchen" second edition from 1819.

Interpretations

editFear was a major topic for Søren Kierkegaard, who wrote Frygt og Bæven in 1843; he uses the fairy tale to show how fear within one's belief system can lead to freedom.

Hedwig von Beit interprets cats as the forerunners of the later ghost: They suggest a game which the ghost plays in some variation too, and are trapped like him.[6] Spirits of the dead appear in animals, and bowling games in fairy tales often consist of skull and bones. The underworldly aspect of the Unconscious appears, when consciousness treats it in a disapproving fashion, just as the naive not actually courageous son does in compensation to the behavior of the others. He naively treats ghosts like real enemies, and does not become panicky, so that the unconscious conflicts can take shape and can be fixated on. The woman shows him the part of life, which he is unconscious of. In many variants he is frightened of looking backward, or of his backside, when his head is put on him the wrong way round, which is interpreted as a view or glimpse of death or the netherworld.[7]

The East German writer Franz Fühmann opined in 1973, that the hero apparently felt he lacked a human dimension.[8] Peter O. Chotjewitz wrote, one had never taught him words for feelings, which he now connects with his supposed stupidity.[9] Bruno Bettelheim's understanding of the fairy tale is that to attain human happiness one has to derepress one's suppressions. Even a child would know repressed, unjustified fears, which appeared at night in bed. Sexual fears would mostly be detested.[10] In 1999, Wilhelm Salber noted the effort, how anxieties are deliberately built up and destroyed using ghosts and animals, to avoid proximity to real life, and only compassion brings movement into it.[11] Egon Fabian and Astrid Thome view the fairy tale as an insight into the psychological need to perceive fear, which otherwise is sought externally and remains internally inaccessible as primal fear ("Urangst").[12]

Maria Tatar wrote in 2004 that although the hero of this story is a youngest son, he does not fit the usual character of such a son, who normally achieves his goals with the aid of magical helpers. Accomplishing his task with his own skill and courage, he fits more in the mold of a heroic character.[13]: 97 The act of cutting down the corpses to let them warm themselves is similar to the test of compassion that many fairy tale heroes face, but where the act typically wins the hero a gift or a magical helper, here it is merely an incident, perhaps a parody of the more typical plot.[14]: 20

The tale is part of the collective of not uncommon stories in which a swine herd, a veteran or a vagrant prince – always someone from "far away" – wins a king's daughter and inherits the father ("half the kingdome" etc.) as in for example the devil with the three golden hairs. It is the story of a matrilineal inheritance in which daughters, and not sons inherit. If the story moves along into a patrilineal society, one needs a strong explanation to understand the solution – here the rare gift, never to be frightened and an unusually resolute wife.[citation needed]

The Child Ballad The Maid Freed from the Gallows has been retold in fairy tale form, focusing on the exploits of the fiancé who must recover a golden ball to save his love from the noose, and the incidents resemble this tale (e.g. spending three nights in a house, a body split in half and a chimney, and an incident on a bed).[15]

Variants

editThe story can also be titled The Boy Who Wanted to Know What Fear Was and The Boy Who Couldn't Shudder.[16]

Jack Zipes, in his notes to the translated tales of Giuseppe Pitrè, notes that the Italian folklorist collected three variants, and compares them to similar tales in Italian scholarly work on folklore, of the late 19th century, such as the works of Laura Gonzenbach and Vittorio Imbriani.[17] He also analyses the variant collected by Laura Gonzenbach (The Fearless Young Man),[18] and cites a predecessor in The Pleasant Nights of Straparola.[19]

Variants in Latin American countries relocate the setting from a haunted castle to a haunted house or haunted farm.[20]

"Sop Doll" is an American variant collected from the Southern Mountains.[21]

Adaptations

editThere are numerous literary adaptations mentioned in the encyclopedia of fairy tales by Heinz Rölleke:[22] Wilhelm Langewiesch in 1842, Hans Christian Andersen's "Little Claus and Big Claus" (1835), Wilhelm Raabes "Der Weg zum Lachen" (1857) and Meister Author (1874), Rainer Kirsch's "Auszog das Fürchten zu lernen" (1978), Günter Wallraffs "Von einem der auszog und das Fürchten lernte" (1979) and fairy tale renditions by Ernst Heinrich Meier, Ludwig Bechstein's ("Das Gruseln" in the 1853 book "Deutsches Märchenbuch" in chapter 80, also "Der beherzte Flötenspieler") and Italo Calvino's "Giovannino senza paura" ("Dauntless Little John"), the first story in his 1956 Italian Folktales.

- In his 1876 opera Siegfried, Richard Wagner has his title character Siegfried begin fearless, and express his wish to learn fear to his foster father Mime, who says the wise learn fear quickly, but the stupid find it more difficult. Later, when he discovers the sleeping Brünnhilde, he is struck with fear. In a letter to his friend Theodor Uhlig, Wagner recounts the fairy tale and points out that the youth and Siegfried are the same character.[13]: 104 Parzival is another figure in German legend that combines naiveté with courage.[14]: 15

- In Hermann Hesse's novel "Der Lateinschüler", the shy protagonist attempts to tell the story to a circle of young girls, who know the story already.[23] Parodies like to play with the title and give Hans an anticapitalist meaning or sketch him as an insecure personality.

- Gerold Späths Hans makes a global career and forgets that he looked for the meaning of fear.[24]

- Rainer Kirsch sketched a film version, in which the hero is murdered by fanning courtiers and thus learns fear too late.

- Karl Hoches hero finds capitalism to be entertaining, only the women's libber doesn't.[25]

- In Janoschs story the man only thinks of bowling and card games, plays night after night with the headless ghost and the princess dies at some point.[26]

- In his autobiography "Beim Häuten der Zwiebel" Günter Grass uses the term 'How I learnt to fear' several times for the title and descriptions of the fourth chapter about his war mission, which he survives seemingly like a naive fairy tale hero.

- The character of the Boy from the webcomic No Rest for the Wicked is based on the protagonist of this story.[27]

The story has also been adapted for television. Jim Henson's The Storyteller featured an adaptation of the tale in the first season, second episode as "Fearnot".[citation needed] Shelley Duvall's TV show Faerie Tale Theatre adapted it as "The Boy Who Left Home to Find Out About the Shivers"[28] In the German cartoon Simsala Grimm the story is featured in the tenth episode of the first season: unlike in the original story, here the youth learns fear when he has to kiss the princess, since he has never been kissed before and fears doing it wrong and embarrassing himself. The episodic games of American McGee's Grimm on Gametap debuted with "A Boy Learns What Fear Is" on 31 July 2008.[citation needed] The MC Frontalot song "Shudders", from his album Question Bedtime, is based on this story.[citation needed]

The title is often varied for example by the band Wir sind Helden in their song "Zieh dir was an: Du hast dich ausgezogen, uns das Fürchten zu lehren…"(translated "Dress yourself, you have undressed yourself to teach us fear…", figuratively meaning "put something on, you've put yourself out to teach fear.").

See also

edit- The Boy Who Found Fear at Last, a Turkish fairy tale with a similar theme

- Ivan Turbincă, a Romanian story tale with a similar theme

References

edit- ^ a b c Ashliman, D. L. (2002). "The Story of a Boy Who Went Forth to Learn Fear". University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 105–106. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Stith Thompson, The Folktale, p. 105, University of California Press, Berkeley Los Angeles London, 1977.

- ^ "Wer den Grimms "Grimms Märchen" erzählte". Die Welt. 17 December 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ Jack Zipes, The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World, p 46, 2002, ISBN 0-312-29380-1

- ^ Brüder Grimm: Kinder- und Hausmärchen, last edition with original annotations of the Brothers Grimm.with an appendix of all fairy tales that are not published in all editions and sources published by Heinz Rölleke. Volume 3: Originalanmerkungen, Herkunftsnachweise, Nachwort. Reclam, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-15-003193-1 tale # 8, No. 20, #91, No. 99, #114, No. 161

- ^ von Beit, Hedwig: Gegensatz und Erneuerung im Märchen. Second Volume of "Symbolik des Märchens" ("Symbolism of the fairy tale"). Second, improved edition, Bern 1956. pp 519–532.(published by A. Francke AG)

- ^ Franz Fühmann: (Das Märchen von dem, der auszog, das Gruseln zu lernen). In: Wolfgang Mieder (editor.): Grimmige Märchen. Prosatexte von Ilse Aichinger bis Martin Walser. Fischer, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X, p 60 (first published in: Franz Fühmann: Zweiundzwanzig Tage oder Die Hälfte des Lebens. Hinstorff, Rostock 1973, p. 99.)

- ^ Peter O. Chotjewitz: Von einem, der auszog, das Fürchten zu lernen. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Hrg.): Grimmige Märchen. Prosatexte von Ilse Aichinger bis Martin Walser. Fischer (publisher), Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X, p. 61-63 (first published in: Jochen Jung (editor): Bilderbogengeschichten. Märchen, Sagen, Abenteuer. Neu erzählt von Autoren unserer Zeit. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag(publisher), München 1976, S. 53–55.)

- ^ Bruno Bettelheim: Kinder brauchen Märchen. 31. edition. 2012. dtv(publisher), München 1980, ISBN 978-3-423-35028-0, p. 328-330

- ^ Wilhelm Salber: Märchenanalyse (= Werkausgabe Wilhelm Salber. volume 12). second edition. Bouvier( publisher), Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-416-02899-6, p. 85-87, 140.

- ^ Egon Fabian, Astrid Thome: Defizitäre Angst, Aggression und Dissoziale Persönlichkeitsstörung. In: Persönlichkeitsstörungen. Theorie und Therapie. volume 1, 2011, ISBN 978-3-7945-2722-9, p. 24-34.

- ^ a b Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales, 1987, ISBN 0-691-06722-8.

- ^ a b Maria Tatar, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, 2004, ISBN 0-393-05848-4.

- ^ Joseph Jacobs, ed., "The Golden Ball", More English Fairy Tales. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1894.

- ^ Sherman, Josepha (2008). Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore. Sharpe Reference. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7656-8047-1

- ^ Zipes, Jack and Russo, Joseph. The Collected Sicilian Folk and Fairy Tales of Giuseppe Pitré. Vol. I. New York and London: Routledge. 2009. pp. 862 and 920. ISBN 0-415-98030-5

- ^ Zipes, Jack. Beautiful Angiola: The Lost Sicilian Folk and Fairy Tales of Laura Gonzenbach. New York and London: Routledge. 2004. p. 36. ISBN 0-415-96808-9

- ^ "Flamminio in Seeking Death Discovers Life." In The Pleasant Nights – Volume 1, edited by Beecher Donald, by Waters W.G., 628-50. Toronto; Buffalo; London: University of Toronto Press, 2012. www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/9781442699519.29.

- ^ Saavedra, Yolando Pino. Cuentos mapuches de Chile. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Universitaria. 2003 [1987]. p. 260. ISBN 956-11-0689-1, 9789561106895

- ^ McCarthy, William (2007). Cinderella in America: A Book of Folk and Fairy Tales. The University Press of Mississippi. pp. 336–341.

- ^ Heinz Rölleke (1987). "Fürchten lernen.". Enzyklopädie des Märchens, vol 5. Berlin, New York. pp. 584–593.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hermann Hesse: Der Lateinschüler. In: Hermann Hesse. Die schönsten Erzählungen. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-518-45638-5, p. 70-100

- ^ Gerold Späth: Kein Märchen von einem, der auszog und das Fürchten nicht lernte. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Hrg.): Grimmige Märchen. Prosatexte von Ilse Aichinger bis Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X, S. 70–71 (first published in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Nr. 302, 24./25. Dezember 1977, S. 37.)

- ^ Karl Hoche: Märchen vom kleinen Gag, der sich auszog, um das Gruseln zu lernen. In: Wolfgang Mieder (Hrg.): Grimmige Märchen. Prosatexte von Ilse Aichinger bis Martin Walser. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt (Main) 1986, ISBN 3-88323-608-X, p. 72-77 (zuerst erschienen in: Karl Hoche: Das Hoche Lied. Satiren und Parodien. Knaur, München 1978, S. 227–233.)

- ^ Janosch: Kegel- und Kartenspiel. In: Janosch erzählt Grimm's Märchen. Fünfzig ausgewählte Märchen, neu erzählt für Kinder von heute. Mit Zeichnungen von Janosch. 8. Auflage. Beltz und Gelberg, Weinheim und Basel 1983, ISBN 3-407-80213-7, S. 176–182.

- ^ "Characters". ForTheWicked.net. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ 1982–1987: Faerie Tale Theater (USA 1982–1987), TV series, on "Showtime". Third Season: The Boy Who Left Home To Find Out About The Shivers.

Further reading

edit- Agosta, Louis. "The Recovery of Feelings in a Folktale". In: Journal of Religion and Health 19, no. 4 (1980): 287–97. www.jstor.org/stable/27505591.

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-60). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 22–37.

External links

edit- Media related to The tale of a youth who set out to learn what fear was at Wikimedia Commons

- Works related to The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was at Wikisource

- The complete set of Grimms' Fairy Tales, including The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was at Standard Ebooks

- The Story of a Boy Who Went Forth to Learn Fear

- The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was Archive.org Story 58

- Folktales of ATU type 326, "The Youth Who Wanted to Learn What Fear Is" by D. L. Ashliman

- The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was from Leonora and Andrew Lang's The Blue Fairy Book on YouTube