The Virgin and the Gypsy is a 1970 British drama film directed by Christopher Miles and starring Joanna Shimkus and Franco Nero. The screenplay by Alan Plater was based on the novella of the same name by D. H. Lawrence. The film was voted "Best Film of the Year" by both the UK and USA critics.[2]

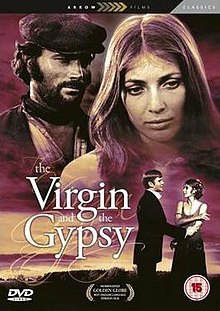

| The Virgin and the Gypsy | |

|---|---|

DVD cover | |

| Directed by | Christopher Miles |

| Written by | Alan Plater |

| Based on | The Virgin and the Gypsy by D. H. Lawrence |

| Produced by | Kenneth Harper |

| Starring | Joanna Shimkus Franco Nero Honor Blackman Mark Burns Fay Compton Maurice Denham |

| Cinematography | Robert Huke |

| Edited by | Paul Davies |

| Music by | Patrick Gowers |

Production company | Kenwood Productions |

| Distributed by | London Screen |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.4 million[1] |

Plot

editBased on a 1928 novella by D. H. Lawrence, published posthumously in 1930, the film follows Yvette, who with her sister Lucille, returns from the relative freedom of a French finishing school to their home, a gloomy rectory in the Midlands. There is immediate tension with her father, a pedantic country rector, her prim maiden aunt Cissie, and her aged grandmother who insidiously rules the house with a rod of matriarchal iron. Yvette’s only real contacts are with her sister Lucille, the seemingly quiet non-entity Uncle Fred and Mary the housemaid.

Yvette feels imprisoned not only by the family, but also the rather empty-headed bright young things of the parish, among whom is Leo Wetherall, an industrialist’s son who is in love with her. During a frivolous car ride with Leo and friends they encounter a gypsy on his cart, a dark arrogant man of few words, who stops the car asking if the ladies want their fortunes told. At the gypsy’s encampment his wife tells Yvette her fortune, telling her to beware of the voice of the water;[clarification needed] this remark and the gypsy himself make a deep impression on Yvette.

Returning to the encampment the following week, she meets a neighbour Mrs Fawcett and her lover Major Eastwood; their obvious defiance of social convention appeals to Yvette, and they become close friends. This friendship creates further tensions in the rectory as her father disapproves of the Eastwoods, and refuses to admit them to a concert Yvette had organised to raise money for her father’s church. Later Yvette gives the funds raised from the concert to the gypsies in revenge.

Recognising the symptoms of rebellion in his wife before she left him, the rector threatens Yvette if she does not change her ways and forbids her to see the Eastwoods again. Temporarily defeated, Yvette says goodbye to the Eastwoods, and they discuss her relationship with the gypsy. On her way biking home, she sees the gypsy’s horse tethered to an old barn door, and on looking briefly inside she sees the gypsy and Mary making love, and for the first time is aware of the man as a reality, not part of a juvenile fantasy.

During Leo’s 21st birthday party, Yvette slaps him in front of everyone, so denying him what he thinks is his right to marry her. From here on the drama deepens, and the voice of the water delivers a surprising and liberating denouement at the end of the film.[3]

Cast

edit- Joanna Shimkus as Yvette

- Franco Nero as the Gypsy

- Honor Blackman as Mrs. Fawcett

- Mark Burns as Major Eastwood

- Fay Compton as Grandma

- Maurice Denham as the Rector

- Kay Walsh as Aunt Cissie

- Imogen Hassall as the Gypsy's Wife

- Harriet Harper as Lucille

- Norman Bird as Uncle Fred

- Jeremy Bulloch as Leo Wetherall

- Roy Holder as Bob

- Margo Andrew as Ella

- Janet Chappell as Mary

Production

editIn 1967 Kenneth Harper, the producer, worked with director Christopher Miles and screenwriter Alan Plater on the script of "The Virgin and the Gypsy" and their first draft was discussed with John Van Eyssen, Chief Production Executive at Columbia Pictures in the UK, who although he had read Lawrence’s story and commissioned the script, wanted the gypsy to appear in the first reel. This Miles felt would not work, as the whole point of the start of the film was to establish the virgin in relationship to her family, and the rectory, and to feel the frustration of the young girl. Also he thought the film would fail unless these elements from Lawrence’s own story were not supported. The producer agreed and so Columbia withdrew their support, costing the film makers two years in their search for alternative finance.[4]

During this time the producer and director had also been considering the problems of casting the two leads, as the word ‘virgin’ had multiple interpretations, which in the new permissive 1960s had become a distraction. Various actors were considered for both leading roles, but on hearing about a new young actress in a French film 'Tante Zita', Miles went to Paris to see the film, and despite another offer Joanna Shimkus accepted the role of Yvette.[5][6]

In 1969 Miles was introduced to Dimitri de Grunwald, who had set up London Screen, whose method of film financing was based on the European model rather that the American one. This meant that the leading actress, Joanna Shimkus, a Canadian who had just started her film career in Paris, along with Franco Nero, who by then was well known in Italy, fitted into Dimitri’s plans for Pan-European production finance. Dimitri was prepared to finance the film with the 29 year old director, as he had seen his first short Oscar nominated film 'The Six-sided Triangle' at his local cinema.[7]

Finding the right locations also proved a problem, as no rectories were built near river banks in the locations Lawrence wrote about, but while searching near Matlock they found ‘Raper Lodge’ a smallish stone built house belonging to the water bailiff of the Duke of Rutland. As this was before the days of CGI an extension was built onto the house which could also be partly destroyed for the flood scene, which was also filmed later in a London studio.[8]

The film was completed on budget in 8 weeks, but during the editing a new UK Film Censorship Category was introduced of a double A - which meant that no one under 14 could see the film. This caused Miles to have a dispute with the censor, but a compromise was reached and an AA certificate was finally granted.[9]

Release

editThe film was shown out of competition at the 1970 Cannes Film Festival on 15 May.[10] The Buttercup Chain, a co-production between Columbia Pictures and Columbia British Productions, was entered as the official British entry to the festival, with huge publicity buttercups shimmering along the Croisette, causing some critics to wonder why The Virgin and the Gypsy, which was shown out of competition, had not been chosen.[11]

The film opened 30 June 1970 at the 68th Street Playhouse in New York City before its "world premiere" at the Odeon in Haymarket, London on 2 July.[12][13] It opened to the public in London on 3 July.[13]

The USA trades predicted poor box office, but the following weeks proved them wrong as the film broke box office records in both London and New York, and continued to earn millions throughout the world.[14]

Critical reception

editFrom the opening credits of a gentle river flowing under the rectory bridge, to the last shot of the dying embers of the gypsy’s fire, it was clear to some critics that the elements of earth, fire and water had a meaning more than their simple images [15] "...the sterile stuffy heat from the rectory fire, against the warmth of the gypsy’s encampment fire - the tranquility of life giving water, which can suddenly become a destructive life changing force. Some also recognised the almost fable-like quality of the main characters, which were archetypes of the weak father and uncle, against the malevolent strength of the grand-mother, all trying unsuccessfully to dominate and stop the flowering of the young virgin herself. Nothing can stop her," said Miles, "She is like a crocus that unerringly and inevitably finds its way up though a road’s tarmac".[16]

The film critic of The Times of London, John Russell Taylor, asked Christopher Miles at the press screening if he had seen the USA Trade reviews. Miles said he hadn't, and Russell Taylor told him not to worry as he had made a "film of much quiet distinction, a highly literate and sympathetic adaptation of the original... excellent performances... as the period background is beautifully, because unobtrusively, captured".[17] The rest of the press were also enthusiastic, which helped promote a film not made by a major US studio.

Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote "An immensely romantic movie with style and critical intelligence. ‘The Virgin and the Gypsy’ is satisfying because it realises its goals".[12] Alexander Walker of the Evening Standard said "It makes a refreshing change to find a film today directed with taste and grace. Director Christopher Miles debut as a feature director reveals a flair for composition, proportion and craftsmanship. I can confidently recommend Kenneth Harper’s production".[18] News Week said “A finely etched portrait of the quiet renegade girl played with erotic daydreams in her eyes by Joanna Shimkus: Franco Nero’s snake-eyed gypsy, all purpose and passion... a finely made film filled with the kind of information only art can provide about a time passed”.[19]

Ian Christie of the Daily Express wrote, ”Christopher Miles has turned this short novel into a work that distils visual poetry”[20] and Judith Crist of the New York Magazine wrote “The screenplay by Alan Plater is nothing short of masterly in putting those ‘final revisions’ on Lawrence’s sketchy story... and the director has an outstanding gift for visual summation... besides Miss Shimkus, who loveliness has a unique and penetrating quality, there are fine performances from Honor Blackman and Mark Burns who know the difference between appetite and desire... and Franco Nero, as the outrageously handsome gypsy the embodiment of every girl’s dream of the noble savage”.[21] While Ernest Betts of The People wrote, “I thought it was impossible to translate D.H.Lawrence to the screen, but with “The Virgin and the Gypsy” I take it all back. This is a perfect screen adaptation and the best sex film we’ve had”.[22] Time Magazine thought “No story - and no film - better reveals Lawrence’s moral absolutism than “The Virgin and the Gypsy”... At 29 Miles knows everything worth knowing about actors... he makes his cast function with the proficiency and timing of a London rep company”.[23]

Awards

edit| Association | Accolade | Recipient | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Globe | Best Foreign Film in the English Language | Christopher Miles | Nominated |

| Golden Laurel | Best Actor | Joanna Shimkus & Franco Nero | Nominated |

References

edit- ^ Leonard Sloane (12 July 1970). "Spotlight:: Financing the Films: New Ideas". The New York Times. p. 100.

- ^ Youlgrave Bugle (June 2020 No. 226) "Remembering the Virgin and the Gypsy"

- ^ Evening Echo - Cork (24 February 1973) "Film of famous D.H.Lawrence story"

- ^ "The Virgin and the Gypsy - an English Watercolor" - S.E Gontarski - The English Novel and the Movies - Frederick Ungar Pub. Co / New York

- ^ Guardian (30 July 1969) "First stab at the blood lust" Robin Hall interviews Christopher Miles

- ^ New York Post (27 June 1970) - "I’m a gypsy I guess" - Joanna Shimkus

- ^ Cinema TV Today (11 January 1975) – “Shared finance the only thing that makes sense – De Grunwald”

- ^ Youlgrave Bugle (June 2020 No. 226) “Remembering the Virgin and the Gypsy”

- ^ Daily Mail (1 July 1970) Cecil Wilson - “X films you must now be 18”

- ^ "Cannes and Here". New York Daily News. 8 May 1970. p. BL70.

- ^ Films in London (Vol 2 No. 26 June 1970 )- Jerry Bauer - In Focus

- ^ a b Canby, Vincent (1 July 1970). "Screen: Virgin and the Gypsy Opens". The New York Times. p. 50. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ a b "World Premiere Thursday (advertisement)". Evening Standard. 29 June 1970. p. 15.

- ^ "Virgin and the Gypsy rescued him". The New York Times. 23 August 1970. p. 8.

- ^ Kanfer, Stefan (13 July 1970). "Fast Company". Time. USA.

- ^ "The Virgin and the Gypsy - an English Watercolor" - S.E Gontarski - The English Novel and the Movies - Frederick Ungar Pub. Co / New York

- ^ The Times (3 July 1970) - The Lady and the Tramp - John Russell Taylor

- ^ Evening Standard Alexander Walker - critic of the year

- ^ "Virgin and the Gypsy (film review)". Newsweek. USA. 13 July 1970.

- ^ Daily Express (1 July 1970) - “Lawrence’s lady learns about sex”

- ^ New York Magazine (22nd June 1970) - Judith Crist “Virgins and Gypsies”

- ^ The People (5 July 1970) - Ernest Betts - ‘This is a winner’

- ^ Kanfer, Stefan (13 July 1970). "Fast Company". Time. USA.f

Further reading

edit- Bryson, Bill. Doubleday Inc/ Transworld Publishers. ‘The road to Little Dribbling’ - The Peak District chapter - ‘The Virgin and the Gypsy’ ISBN 9780857522344

- Butler, Ivan. A.S.Barnes and Co. Inc/The Tantivy Press, London W1Y OQX "Cinema in Britain - 1970 The Virgin and the Gypsy" ISBN 0-498-01133-X

- Gontarski, S.E. Ed. Michael Klein & Gilian Parker. Frederick Ungar Publishing Co / New York "The English Novel and the Movies" - "The Virgin and the Gypsy" - An English Watercolor ISBN 0-8044-2472-1

- Greiff, Louis K. Southern Illinois University Press. "D.H.Lawrence - Fifty Years on Film" 'Foxes and Gypsies on Film’ ISBN 0-8093-2387-7

- Lawrence, D.H. "The Virgin and the Gypsy" First Published (single volume) Martin Secker Ltd. 1930. Single volume paperback - Penguin Books

- Vermilye, Jerry. Published by Citadel Press - Lyle Stuart Inc. "The great British films" - 244 ‘The Virgin and the Gypsy’ ISBN 0-8065-0661-X

- Gilliat, Penelope. "The England, this Past" New Yorker, 4 July 1970, p. 71

- Hart, Henry. "1970's Ten Best" Films in Review - Feb. 1971 p. 63

- Kauffmann, Stanley. "Stanley Kauffmann on Films" New Republic, 1 August 1970, p. 24.

- Moore, Harry T. "D.H.Lawrence and the Flicks" - Literature/Film Quarterly Southern Illinois University. Vol 1 No 1 1974