Poltergeist is a 1982 American supernatural horror film directed by Tobe Hooper and written by Steven Spielberg, Michael Grais, and Mark Victor from a story by Spielberg. It stars JoBeth Williams, Craig T. Nelson, and Beatrice Straight, and was produced by Spielberg and Frank Marshall. The film focuses on a suburban family whose home is invaded by malevolent ghosts that abduct their youngest daughter.

| Poltergeist | |

|---|---|

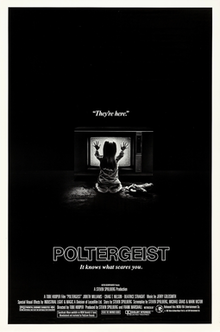

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tobe Hooper |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Steven Spielberg |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Matthew F. Leonetti |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | MGM/UA Entertainment Co. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10.7 million |

| Box office | $121.7 million[2] |

As Spielberg was contractually unable to direct another film while he made E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Hooper was selected based on his work on The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Funhouse. The origin of Poltergeist can be traced to Night Skies, which Spielberg conceived as a horror sequel to his 1977 film Close Encounters of the Third Kind; Hooper was less interested in the sci-fi elements and suggested they collaborate on a ghost story.[3] Accounts differ as to the level of Spielberg's involvement, but it is clear that he was frequently on set during filming and exerted significant creative control. For that reason, some have said that Spielberg should be considered the film's co-director or even main director, though both Spielberg and Hooper have disputed this.

Released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer through MGM/UA Entertainment Co. on June 4, 1982, Poltergeist was a major critical and commercial success, becoming the eighth-highest-grossing film of 1982. In the years since its release, the film has been recognized as a horror classic. It was nominated for three Academy Awards, named by the Chicago Film Critics Association as the 20th-scariest film ever made, and a scene made Bravo's 100 Scariest Movie Moments.[4][5] Poltergeist also appeared at No. 84 on American Film Institute's 100 Years...100 Thrills.[6] The film was followed by Poltergeist II: The Other Side (1986), Poltergeist III (1988), as well as a 2015 remake, but none had the critical success of the original.

Plot

editSteven and Diane Freeling live in the planned community of Cuesta Verde, California. Steven is a successful real estate agent, and Diane looks after their three children: sixteen-year-old Dana, eight-year-old Robbie, and five-year-old Carol Anne. Late one night, Carol Anne inexplicably converses with the family's television set while it displays post-broadcast static. The next night, she fixates on the television again, and a ghostly white hand emerges from the screen, followed by a violent earthquake. As the family is shaken awake by the quake, Carol Anne eerily intones, "They're here."

The following day is filled with bizarre events: a glass of milk spontaneously breaks, silverware bends, and furniture moves on its own. These phenomena initially seem benign, but soon grow sinister. During a severe thunderstorm, the gnarled backyard tree seemingly comes alive. A large limb crashes through the children's bedroom window, grabs Robbie, pulls him outside into the pouring rain and attempts to devour him. While the family rushes outside to rescue Robbie, Carol Anne is pulled into a portal inside the closet. After saving Robbie from the tree, which got sucked into a tornado, the family frantically search for Carol Anne, only for her voice to call out from the television.

Parapsychologist Martha Lesh arrives with team members Ryan and Marty to investigate. They determine there is a poltergeist intrusion involving multiple ghosts. Meanwhile, Steven learns from his boss Lewis Teague that the Cuesta Verde development was built on a former cemetery and the graves were moved to a nearby location.

Dana and Robbie are sent away for safety, while Dr. Lesh calls in Tangina Barrons, a spiritual medium. Tangina divulges the spirits are lingering in a different "sphere of consciousness" and are not at rest. They are attracted to Carol Anne's life force. Tangina also detects a dark presence she calls the "Beast", who is restraining Carol Anne and manipulating her life force in order to prevent the other spirits from crossing over.

The entrance to the other dimension is in the children's bedroom closet and exits through the living room ceiling. Diane, secured by a rope, passes through the portal, guided by another rope previously threaded through both portals. Diane retrieves Carol Anne, and they drop through the ceiling to the living room floor, covered in ectoplasm. As they recover from the ordeal, Tangina proclaims the house is "clean".

Shortly after, the Freeling family have nearly finished packing to move out of the house. Before the family is to leave, Steven goes to his office while Dana is on a date, leaving Diane at home with Robbie and Carol Anne. The "Beast" ambushes Diane and the children, aiming for a second kidnapping attempt. The unseen force drives Diane to the backyard in the pouring rain, where she stumbles into the flooded swimming pool excavation. Skeletal corpses and coffins float up around her in the muddy hole. Diane crawls out and rushes back into the house. She rescues the children, and they narrowly escape outside as more coffins and bodies erupt from the ground.

Accompanied by Teague, Steven arrives home to the mayhem and realizes that only the gravestones were relocated; the development was built over the abandoned graves. The Freelings jump into their car and collect Dana just as she returns home. They flee Cuesta Verde as the house implodes into a portal while Teague and stunned neighbors look on. The family checks into a room at a Holiday Inn, where Steven promptly removes the TV.

Cast

edit- Craig T. Nelson as Steven "Steve" Freeling

- JoBeth Williams as Diane Freeling

- Beatrice Straight as Dr. Lesh

- Dominique Dunne as Dana Freeling

- Oliver Robins as Robbie Freeling

- Heather O'Rourke as Carol Anne Freeling

- Michael McManus as Ben Tuthill

- Virginia Kiser as Mrs. Tuthill

- Martin Casella as Dr. Marty Casey

- Richard Lawson as Dr. Ryan Mitchell

- Zelda Rubinstein as Tangina Barrons

- James Karen as Mr. Lewis Teague

- Dirk Blocker as Jeff Shaw

- Lou Perry as Pugsley

- Sonny Landham as Pool Worker

Production

editMichael Grais and Mark Victor had written an unproduced comedy called Turn Left And Die and the action film Death Hunt, when Steven Spielberg decided to invite them to possibly work with him. After screening A Guy Named Joe for them and saying he wanted to remake that film—which he would in 1989's Always—Spielberg also mentioned a ghost story idea he intended to turn into a script. Grais called Spielberg the next day saying he and Victor only had interest in the ghost story, and after plans with another writer fell through, Spielberg brought the two to the job.[7] Spielberg wanted Stephen King to co-write the screenplay, but he was unavailable.[8]

Principal photography rolled mostly on Roxbury Street in Simi Valley, California.[9][10] Following completion of principal photography in the first week of August 1981, Hooper went on to spend ten weeks in the editing room, compiling the first cut of the film.[11] During much of this time, Spielberg was at Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), supervising the visual effects photography.

Creative credit

editA clause in Spielberg's contract with Universal Studios prevented him from directing another film while preparing E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.[12] According to Tobe Hooper, the core concept of the film was an idea he pitched to Spielberg after turning down the offer to direct Night Skies.[13] Writer Michael Grais stated that "we weren't really 'working' with Spielberg because he was on E.T.", and that Spielberg only had sporadic meetings with the writers in MGM's commissary.[7] E.T. and Poltergeist were released a week apart in June, 1982; Time and Newsweek referred to it as "The Spielberg Summer". There were suggestions that Spielberg, in addition to being Poltergeist's co-producer and co-writer, had also served as its de facto co-director. This view was bolstered by various statements Spielberg made about his involvement, including a Los Angeles Times quote on May 24, 1982: "Tobe isn't ... a take-charge sort of guy. If a question was asked and an answer wasn't immediately forthcoming, I'd jump in and say what we could do. Tobe would nod agreement, and that became the process of collaboration."[14]

That same article noted that the Directors Guild of America had opened an investigation into the "question of whether or not Hooper's official credit was being denigrated by statements Spielberg has made, apparently claiming authorship."[15] The investigation ended in an arbitrator's ruling that MGM/UA Entertainment Co. must pay $15,000 to Hooper because the studio gave producer Spielberg a bigger credit than Hooper got in its trailers, although also noting that "broader issues of dispute exist between producer-writer (Spielberg) and the director" (damages of $200,000 were originally sought by the DGA).[16] Co-producer Frank Marshall told the LA Times that "the creative force of the movie was Steven. Tobe was the director and was on the set every day. But Steven did the design for every storyboard, and he was on the set every day except for three days when he was in Hawaii with Lucas." However, Hooper stated that he "did fully half of the storyboards."[12]

The week of the film's release, The Hollywood Reporter printed an open letter from Spielberg to Hooper:

Regrettably, some of the press has misunderstood the rather unique, creative relationship which you and I shared throughout the making of Poltergeist.

I enjoyed your openness in allowing me, as a writer and a producer, a wide berth for creative involvement, just as I know you were happy with the freedom you had to direct Poltergeist so wonderfully.

Through the screenplay you accepted a vision of this very intense movie from the start, and as the director, you delivered the goods. You performed responsibly and professionally throughout, and I wish you great success on your next project.[17]

In a 2007 Ain't It Cool News interview, Zelda Rubinstein discussed her recollections of the shooting process. She said "Steven directed all six days" she was on set: "Tobe set up the shots and Steven made the adjustments." She also alleged that Hooper "allowed some unacceptable chemical agents into his work," and that during her audition, "Tobe was only partially there."[18] Comments from actor James Karen, concerning a 25th-anniversary Q&A event which both attended, categorized Rubinstein's remarks as unfair to Hooper. "She laid into Tobe and I don't know why ... Tobe was kind to her."[19]

In a 2012 Rue Morgue article commemorating Poltergeist's 30th anniversary, interviews were conducted with several cast and crew members. In response to the magazine's query about the authorship issue, cast members unanimously sided with Hooper. James Karen said, "Tobe had a hard time on that film. It's tough when a producer is on set every day and there's always been a lot of talk about that. I considered Tobe my director. That's my stand on all those rumours." Martin Casella stated: "So much of Poltergeist looks and feels like a Spielberg movie but my recollection is that Tobe was mostly directing." Oliver Robins: "The guy who sets up the shots, blocks the actors and works with the crew to create a vision is the director. In those terms, Tobe was the director. He's the one who directed me, anyway." Make-up and effects artist Craig Reardon said Spielberg often had the final say. The original version of the cancerous steak, for instance, was created by Reardon per Hooper's specifications—but vetoed by Spielberg: "Although the first steak did not represent a killing amount of work, it had consumed enough time and effort—none of which I could afford to waste—that I determined in the future to make certain whatever I prepped would be approved in advance by Spielberg as well as Hooper."[19]

Hooper was asked about the controversy in a 2015 interview with online journal Film Talk and said the rumors originated from a Los Angeles Times article which reported on Spielberg shooting footage of "little race cars" in front of the house, while Hooper was busy elsewhere shooting another scene. "From there it became its own legend. That is how I remember it; I was making the movie and later on, I heard this stuff after it was finished. I really can’t set the record much straighter than that."[20]

According to the Blumhouse Productions website, first assistant cameraman John R. Leonetti reported that Spielberg directed the film more so than Hooper, stating, "Hooper was so nice and just happy to be there. He creatively had input. Steven developed the movie, and it was his to direct, except there was anticipation of a director's strike, so he was 'the producer' but really, he directed it in case there was going to be a strike and Tobe was cool with that. It wasn't anything against Tobe. Every once in a while, he would actually leave the set and let Tobe do a few things just because. But really, Steven directed it."[21]

Following Hooper's passing in 2017, director Mick Garris, a publicist on the film who made several on-set visits, came to Hooper's defense on the Post Mortem podcast:

Tobe was always calling action and cut. Tobe had been deeply involved in all of the pre-production and everything. But Steven is a guy who will come in and call the shots. And so, you're on your first studio film, hired by Steven Spielberg, who is enthusiastically involved in this movie. Are you gonna say, 'Stop that... let me do this'? Which [Tobe] did.

[...] Tobe was a terrific filmmaker. I don't think it's that Steven was controlling. I think it was Steven was enthusiastic. And nobody was there to protect Tobe. But all of the pre-production was done by Tobe. Tobe was there throughout. Tobe's vision is very much realized there. And Tobe got credit because he deserved credit. Including... Steven Spielberg said that.

[...] Yes, Steven Spielberg was very much involved. It's a Tobe Hooper film.[22]

Special effects

editThe special effects for Poltergeist were produced by Industrial Light and Magic and overseen by Richard Edlund. The film won the BAFTA Award for Best Special Visual Effects and earned a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, which it lost to E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

The scene of Diane (JoBeth Williams) climbing up the walls was done using a static camera in a rotating set.[23] A similar effect was used in Royal Wedding to make it look like Fred Astaire was dancing on the ceiling.

Spielberg recalled that the most complicated lighting effects were used in Carol Anne's closet: "There were so many lighting effects: strobes and Las Vegas spots and fish tanks of water to give different kind of diffusion to the beams coming out and four large wind machines... We wanted the light to live."[24]

The dolly zoom is used in the scene of Diane running down the hallway to Carol Anne's room. This is done by pulling the camera back while zooming the lens forward. In Poltergeist it creates the illusion of expanding space.[25]

Music

editThe music for Poltergeist was written by Jerry Goldsmith, who recalled:

Steven Spielberg called me about five months before [Poltergeist] went into production and wanted to know if I would be interested in doing it. He’d long been an admirer of mine, and we had met several times. I said I’d be very interested, so he sent me a script and I loved it. I was very excited about being involved with anything with Spielberg, anyway... With Spielberg, probably more than any other director, there’s a tremendous amount of discussion. He’s very articulate about music, and one can discuss for hours about approaches. Anything I did was not on my own volition; it was a joint effort in that we both agreed what we were trying to do with the music for the picture. We wanted a childlike theme for the little girl; Spielberg felt that much of the action in the closet should have a quasi-religious atmosphere to it. There was something definitely non-human about it, yet it was not evil all the way. It was discussing specifics like that which resulted in our approach... [Tobe Hooper] was not involved at all with post-production. That was all strictly with Steven, and I worked very closely with him.[26]

Goldsmith wrote several themes for the score, including the lullaby "Carol Anne's Theme" to represent blissful suburban life and the young female protagonist; a semi-religious melody for the souls caught between worlds; and several dissonant, atonal blasts for moments of terror.[27][28] The score went on to garner Goldsmith an Oscar nomination for Best Original Score, though he lost to John Williams for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

Goldsmith's score was first released in 1982 on LP through MGM Records in a 38-minute version. Rhino Movie Music later released a 68-minute cut on CD in 1997. A two-disc soundtrack album later followed on December 9, 2010 by Film Score Monthly featuring additional source and alternate material. The 2010 release also included previously unreleased tracks from Goldsmith's score to The Prize (1963).[27][29]

There is an alternate version of "Carol Anne's theme" which has lyrics. That version is unofficially titled "Bless this House" (which is a line from the chorus). It was not featured in the film but was part of the original album.

Allusions

editA clip of Spencer Tracy in A Guy Named Joe (1943) can be seen on the TV in the Freelings' bedroom. This is one of Spielberg's favorite childhood films, which he would remake as Always. Joe is also a film about the afterlife.

Posters for Star Wars and Alien can be seen in the room shared by Robbie and Carol Anne.

The story of Poltergeist has similarities to The Twilight Zone episode "Little Girl Lost", about a girl who finds a portal to another dimension in her bedroom; the girl's family (including the dog) can hear her but can't see her. The similarity was noted by the episode's author, Richard Matheson: "They sort of used that idea and made their own concept of it." Matheson said he had a positive relationship with Spielberg, adding "God knows the man has talent."[30]

A sign at the Holiday Inn reads "Welcome Doctor Fantasy and Friends". This is an inside joke; producer Frank Marshall is an amateur magician, and his stage-name is Dr. Fantasy.[31] After a production wraps, Marshall performs magic for the crew.[32]

Release

editMPAA rating

editPoltergeist initially received an R rating[33] from the MPAA. Steven Spielberg and Tobe Hooper disagreed with the R rating and succeeded in changing it to PG on appeal.[34]

Reissues

editThe film was reissued on October 29, 1982, to take advantage of the Halloween weekend. It was shown in theaters for one night only on October 4, 2007, to promote the new restored and remastered 25th-anniversary DVD, released five days later. This event also included the documentary They Are Here: The Real World of Poltergeists, which was created for the new DVD.

The Poltergeist franchise is believed by some to be cursed due to the premature deaths of several people associated with the film (including Heather O'Rourke and Dominique Dunne),[35] a notion that was the focus of an E! True Hollywood Story.

Home media

editPoltergeist was released by MGM/UA Home Video on VHS, Betamax, CED, and LaserDisc in 1982. On April 8, 1997, MGM Home Entertainment released Poltergeist on DVD in a snap case, and the only special feature was a trailer. In 1998, Poltergeist was re-released on DVD with the same cover and disc as the 1997 release, but in a keep case and with an eight-page booklet. In 1999, a snap case edition with the same DVD disc, but a different cover, was released by Warner Home Video (later Warner Bros. Home Entertainment), after the pre-May 1986 MGM library was acquired by the Time Warner-owned Turner Entertainment Co. Warner tentatively scheduled releases for the 25th anniversary edition of the film on standard DVD, HD DVD, and Blu-ray[36] in Spain and the US on October 9, 2007. The re-release was billed as having digitally remastered picture and sound, and a two-part documentary: They Are Here: The Real World of Poltergeists, which makes extensive use of clips from the film. The remastered DVD of the film was released as scheduled, but both high-definition releases were eventually canceled. Warner rescheduled the high-definition version of the film, and eventually released it only on the Blu-ray format on October 14, 2008.[37]

To commemorate the film's 40th anniversary, Poltergeist was released by Warner Bros. on 4K UHD Blu-ray on September 20, 2022.[38]

Novelization

editA novelization was written by James Kahn, adapted from the film's original screenplay. It was printed in the United States through Warner Books, with the first printing in May 1982.[39] While the film focuses mainly on the Freeling family, much of the book leans toward the relationship between Tangina and Dr. Lesh. The novel also expands upon many scenes from the film, such as the nighttime manifestation of outer-dimensional entities of fire and shadows in the Freelings' living room, and an extended version of the kitchen scene in which Marty watches a steak crawl across a countertop. In the book, Marty is frozen in place and skeletonized by spiders and rats. There are also additional elements not in the film, such as Robbie's mysterious discovery of the clown doll in the yard during his birthday party, and a benevolent spirit, "The Waiting Woman", who protects Carol Anne in the spirit world.

Reception

editBox office

editPoltergeist was released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer on June 4, 1982.[40] The film was a commercial success and earned $76,606,280 in the United States, making it the highest-grossing horror film of 1982, and eighth overall for the year.[41]

Critical response

editThe film was well received by critics and is considered by many as a classic of the horror genre[42][43] as well as one of the best films of 1982.[44][45][46] On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes it has an approval rating of 88% based on reviews from 72 critics, with an average rating of 7.50/10. The site's consensus reads: "Smartly filmed, tightly scripted, and—most importantly—consistently frightening, Poltergeist is a modern horror classic."[47] On Metacritic it has a score of 79% based on reviews from 16 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[48] Roger Ebert gave Poltergeist three stars out of four and called it "an effective thriller, not so much because of the special effects, as because Hooper and Spielberg have tried to see the movie's strange events through the eyes of the family members, instead of just standing back and letting the special effects overwhelm the cast along with the audience."[49] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called it "a marvelously spooky ghost story" with "extraordinary technical effects" that were "often eerie and beautiful but also occasionally vividly gruesome."[50] Andrew Sarris, in The Village Voice, wrote that when Carol Anne is lost, the parents and the two older children "come together in blood-kin empathy to form a larger-than-life family that will reach down to the gates of hell to save its loved ones."[51] In the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, Peter Rainer wrote:

Buried within the plot of Poltergeist is a basic, splendid fairy tale scheme: the story of a little girl who puts her parents through the most outrageous tribulation to prove their love for her. Underlying most fairy tales is a common theme: the comforts of family. Virtually all fairy tales begin with a disrupting of the family order, and their conclusion is usually a return to order.[51]

David Thomson, in his entry on Spielberg in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, calls Poltergeist "wondrous."[52]

Not all reviews were as positive. Gene Siskel gave the film one-and-a-half stars out of four, writing that Poltergeist "is very good at getting the details of suburban life right—in other words, it sets its stage beautifully—but when it comes time for the terror to begin, the whole thing is very, very silly."[53] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post observed that the film "looks and feels decidedly patchy, as if it had been assembled by different hands frequently working at cross purposes."[54] Sheila Benson of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "In terms of simple, flat-out, roof-rattling fright, Poltergeist gives full value. In terms of story, however, simple is indeed the word, and dumb might be a better one. And when so many effects are lavished on a story this frail, you have a lopsided film."[55]

Accolades

editThe film continues to receive recognition 40 years after its release. Poltergeist was selected by The New York Times as one of The Best 1000 Movies Ever Made.[56] It also received recognition from the American Film Institute, with a number 84 ranking on AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills list;[57] "They're here" was named the 69th-greatest movie quote on AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes.[58]

The film received three Oscar nominations: Best Original Score, Best Sound Effects Editing, and Best Visual Effects, losing all three to Spielberg's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.[59]

| Year | Association | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | Academy Awards | Academy Award for Best Original Score | Nominated |

| Academy Award for Best Sound Effects Editing | Nominated | ||

| Academy Award for Best Visual Effects | Nominated | ||

| Saturn Award | Saturn Award for Best Horror or Thriller Film | Won | |

| Saturn Award for Best Make-up | Won | ||

| Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actress – Zelda Rubinstein | Won | ||

| Saturn Award for Best Actress – JoBeth Williams | Nominated | ||

| Saturn Award for Best Director – Tobe Hooper | Nominated | ||

| Saturn Award for Best Music – Jerry Goldsmith | Nominated | ||

| British Academy Film Awards | BAFTA Award for Best Special Visual Effects | Won | |

| Young Artist Awards | Young Artist Award for Best Younger Supporting Actress – Heather O'Rourke | Nominated |

Legacy

editSequels and remakes

editIn 1986, Poltergeist II: The Other Side retained the family but introduced a new motive for the Beast's behavior, tying him to an evil cult leader named Henry Kane, who led his religious sect to their doom in the 1820s. As the Beast, Kane went to extraordinary lengths to keep his "flock" under his control, even in death. The original motive of the cemetery's souls disturbed by the housing development was thereby altered; the cemetery was now explained to be built above a cave where Kane and his flock met their ends. It also reveals that the women of the family are actually psychics.

Poltergeist III, released in 1988, finds Carol Anne as the sole original family member living in an elaborate Chicago skyscraper owned and inhabited by her aunt, uncle and cousin. Kane follows her there and uses the building's ubiquitous decorative mirrors as a portal to the Earthly plane.

The 1988 Italian film Ghosthouse (also known as La casa 3), written and directed by Umberto Lenzi, has been described as an imitation of the original Poltergeist.[60][61]

In 2013, a remake of the original Poltergeist, produced by MGM and 20th Century Fox and directed by Gil Kenan, was announced.[62][63][64] Sam Raimi, Rob Tapert, and Roy Lee produced the film, which stars Sam Rockwell, Jared Harris, and Rosemarie DeWitt.[65] Poltergeist was released on May 22, 2015.[65]

On April 10, 2019, it was announced that the Russo Brothers would helm a new remake.[66]

In October 2023, it was reported that a television series adaptation was in early development at Amazon MGM Studios with Amblin Television's Darryl Frank and Justin Falvey set to executive produce.[67]

In popular culture

edit"Bad Dream House", the first segment of "Treehouse of Horror", the first episode of the annual The Simpsons Treehouse of Horror Halloween specials, is partly a parody of Poltergeist.

The song "Shining" by horror punk band Misfits, on their 1997 album American Psycho, is based directly on the film, with the chorus centered on the refrain: "Carol Anne, Carol Anne".[68]

Spice Girls pays homage to the film in their 1997 music video for the song "Too Much".[69][70]

Two separate animated TV series helmed by Seth MacFarlane have parodied Poltergeist. In the 2006 Family Guy episode "Petergeist", Peter Griffin discovers an Indian burial ground when he attempts to build a multiplex in a backyard. When he takes an Indian chief's skull, a poltergeist invades the Griffins' home. The episode used some of the same musical cues heard in the film and recreates several of its scenes.[71] American Dad! also parodied the film with the season 10 episode "Poltergasm", in which the Smith house has become haunted by Francine's unsatisfied sex drive, and Roger plays Ruby Zeldastein, a parody of Tangina.[72]

The 2001 comedy horror film Scary Movie 2 parodies the movie's clown doll attack in Robbie's bedroom, as well as Diane's levitation.[73]

Poltergeist was the subject of walk through attractions at both Universal Studios Orlando and Hollywood's annual Halloween Horror Nights event.[74]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "POLTERGEIST (15)". British Board of Film Classification. July 29, 1982. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ "Box Office Information for Poltergeist". The Numbers. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ Martin, Bob (1982). Fangoria #23, Article "Tobe Hooper on Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Poltergeist". pp. 28.

- ^ "Bravo's The 100 Scariest Movie Moments". Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Chicago Critics' Scariest Films". AltFilmGuide.com. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ a b How Did This Get Made: A Conversation With Michael Grais, Writer Of 'Cool World'

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (April 5, 2018). "The untold story of Stephen King and Steven Spielberg's (almost) collaborations". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Kendrick, James (2014). Darkness in the Bliss-Out: A Reconsideration of the Films of Steven Spielberg. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. Page 41. ISBN 9781441146045.

- ^ Epting, Chris (2003). James Dean Died Here: The Locations of America's Pop Culture Landmarks. Santa Monica Press. Page 204. ISBN 9781891661310.

- ^ Sanello, Frank (August 5, 2002). Spielberg: The Man, the Movies, the Mythology. Taylor Trade Publications. p. 119. ISBN 9780878331482.

- ^ a b Brode, Douglas (2000). The Films of Steven Spielberg. New York: Citadel Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-8065-1951-7.

- ^ "Fangoria 023 c2c 1982 Evil Dead scan by SproutHatesWatermarks S" – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Brode, pg 102

- ^ Pollack, Dale (May 24, 1982). "'Poltergeist': Whose Film Is It?". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Searles, Jack (June 19, 1982). "Hooper gets some recognition". Los Angeles Herald Examiner.

- ^ Brode, pg 99–100

- ^ "Click over, children! All are welcome! All welcome! Quint interviews Zelda Rubinstein!!!!". Ain't It Cool News. October 2, 2007. Retrieved January 6, 2008.

- ^ a b "30 Years of Poltergeist". Rue Morgue. No. 121. 2012 – via Web Archive.

- ^ "Tobe Hooper: "I always wanted to work in the time before I was born"". Film Talk. April 17, 2015. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Galluzzo, Rob (July 14, 2017). "Confirmation? Who Really Directed POLTERGEIST?". Blumhouse Productions. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ John Squires (September 14, 2017). "Mick Garris Delivers Final Word on 'Poltergeist' Controversy; "Tobe Directed That Movie."". Bloody-Disgusting.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (September 22, 2022). "What Really Happened During the Making of 'Poltergeist'". Vanity Fair.

- ^ Frank, Marshall (director) (1982). The Making of Poltergeist (Motion picture). Amblin Entertainment.

- ^ Moynihan, Tim (August 28, 2014). "WTF Just Happened: How Do They Pull Off the Vertigo Effect in Movies". Wired.

- ^ Larson, Randall D. (1983). "Jerry Goldsmith on Poltergeist and NIMH". CinemaScore.

- ^ a b "Filmtracks: Poltergeist (Jerry Goldsmith)". Filmtracks.com. December 31, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- ^ Poltergeist soundtrack review at AllMusic, accessed February 16, 2011.

- ^ "Poltergeist". Film Score Monthly. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- ^ "The Script's Development (Page 1 of 2) @ poltergeist.poltergeistiii.com". www.poltergeist.poltergeistiii.com.

- ^ Anderson, Ross (May 23, 2019). Pulling a Rabbit Out of a Hat: The Making of Roger Rabbit. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-4968-2230-7.

- ^ "Calling The Shots No. 39: Frank Marshall". BBC.

- ^ "Poltergeist (1982)". filmratings.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ "Spielberg's 'Poltergeist' Reclassified". Albuquerque Journal. May 24, 1982. p. A15.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara. "Poltergeist Deaths", Snopes.com, August 17, 2007

- ^ "Live Chat with Warner Home Video". Home Theater Forum. February 26, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Poltergeist on Blu-ray at WBshop.com

- ^ Poltergeist and The Lost Boys Hit 4K Blu-ray With Anniversary Editions at ComicBook.com

- ^ Kahn, James (1982). Poltergeist (9780446302227): James Kahn: Books. Warner Books. ISBN 0446302228.

- ^ Woofter, Kristopher, ed. (2021). American Twilight: The Cinema of Tobe Hooper. Austin, Tex.: University of Texas Press. p. 329. ISBN 9781477322833.

- ^ "Box Office Information for Poltergeist". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Poltergeist Movie Reviews, Page 2". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Poltergeist Movie Reviews, Page 3". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "The Greatest Films of 1982". AMC FilmSite.org. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "The 10 Best Movies of 1982". Film.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2018. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "The Best Movies of 1982 by Rank". Films101.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Poltergeist". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ "Poltergeist". Metacritic. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 1, 1982). "Poltergeist". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (June 4, 1982). "Film: 'Poltergeist' From Spielberg". The New York Times. p. C16.

- ^ a b Cited in Brode, p. 111

- ^ Thomson, David (2004). The New Biographical Dictionary of Film. p. 848.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (June 4, 1982). "As a screamer, 'Poltergeist' is mute". Chicago Tribune. Section 3, p. 3.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (June 4, 1982). "Horror With the Spielberg Touch". The Washington Post. p. D1.

- ^ Benson, Sheila (June 4, 1982). "An Epic Bump By Spielberg". Los Angeles Times. Part VI, p. 1.

- ^ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. April 29, 2003. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ Poltergeist at oscars.org; Accessed November 2, 2010.

- ^ Golden, Christopher; Bissette, Stephen R.; Sniegoski, Thomas E. (2000). Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The Monster Book. Simon & Schuster. p. 285. ISBN 978-0671042592.

- ^ Newman, Kim (2011). Nightmare Movies: Horror on Screen Since the 1960s. Bloomsbury USA. p. 262. ISBN 978-1408805039.

- ^ Team, The Deadline (June 20, 2013). "MGM, Fox 2000 To Co-Finance & Distribute 'Poltergeist'; Production To Start This Fall".

- ^ McNary, Dave (March 7, 2013). "'Poltergeist' Reboot Set For Late-Summer Start". Variety.

- ^ Goldberg, Matt (June 20, 2013). "Poltergeist Remake Confirmed to Shoot This Fall; Likely Due out Next Year". Collider.com. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Dave McNary (March 5, 2015). "'Poltergeist' Reboot Moved Up to May 22, 'Spy' Back to June 5". Variety. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ Miska, Brad (April 10, 2019). "'Poltergeist' Getting Remade *Again* with 'Captain America' and 'Avengers' Directors?!".

- ^ Otterson, Joe (October 30, 2023). "'Poltergeist' TV Series in Early Development at Amazon MGM Studios (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ Greene, James R. Jr. (2013). This Music Leaves Stains: The Complete Story of the Misfits. Scarecrow Press ISBN 0810884372

- ^ Strecker, Erin (November 4, 2014). "Happy Birthday, 'Spiceworld': It's Time to Re-Watch Some Cheesy Spice Girls Music Videos". Billboard. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ Munzenrieder, Kyle (November 28, 2018). "From Ariana to Madonna: A History of Pop Stars Recreating Iconic Movies in Their Music Videos". W. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ "Petergeist". TV.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ^ "American Dad: "Poltergasm"". October 7, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ Raymond, Adam K. (April 15, 2013). "Every Movie 'Spoofed' in the Scary Movie Franchise". Vulture.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Foutch, Haleigh (August 9, 2018). "Halloween Horror Nights Adds 'Poltergeist' to 2018 Mazes". Collider. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

External links

edit- Media related to Poltergeist (1982 film) at Wikimedia Commons

- Quotations related to Poltergeist (1982 film) at Wikiquote

- Poltergeist at IMDb

- Poltergeist at AllMovie

- Poltergeist at the TCM Movie Database

- Poltergeist at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films