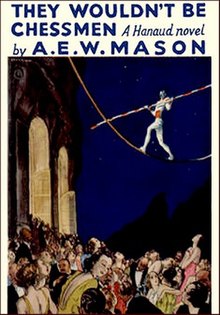

They Wouldn't Be Chessmen is a 1935 British detective novel by A.E.W. Mason. It is the fourth full-length novel in Mason's Inspector Hanaud series.

First edition (UK) | |

| Author | A. E. W. Mason |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Series | Inspector Hanaud |

| Genre | Detective fiction |

| Publisher | Hodder & Stoughton (UK)[1] Doubleday Doran (US) |

Publication date | 1935 [1] |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 343[1] |

| Preceded by | The Prisoner in the Opal |

| Followed by | The House in Lordship Lane |

Plot

editNahendra Nao, heir to the Maharajah of Chitipur, unwisely lets Elsie Marsh of the Casino de Paris wear his priceless ancestral pearls, which react badly to her skin. In order to restore their lustre, his secretary, Major Scott Carruthers, hires a resting young opera singer, Lydia Flight, to wear them while they heal. To provide cover, Lydia is to act as paid companion to a woman introduced by Carruthers, Lucrece Bouchette; while Oliver Ransom, an ex-Captain of the Bengal Police, is added to the party to protect the pearls. Lydia and Ransom are immediately attracted to each other and become a couple.

The party take a houseboat on the Seine near Caudebec-en-Caux, and make the acquaintance of Julius Ricardo. He senses an uneasy atmosphere, and is on his guard when Guy Stallard, an American millionaire, invites him and the houseboat party to a fancy dress ball at a large house he has rented nearby.

While most of the guests are on the terrace watching a tightrope walker, Lydia goes upstairs to change her dress, followed by Ransom. She stumbles back downstairs, on the point of swooning, explaining later that she had been attacked in her room and the pearls taken from her. Shortly afterwards, Ricardo sees Ransom’s car being driven away at speed.

When Carruthers reports the theft to Nahendra Nao, Nao calls in the famous investigator from the Paris Sûreté, Inspector Hanaud, an old friend of Ricardo’s. Lydia arranges a meeting with Hanaud and promises to explain what happened to her, but when she fails to appear and Ransom cannot be found it seems that the pair may have been accomplices and thieves.

Hanaud eventually discovers that Carruthers had for some time been plotting to steal the jewels, to frame Lydia, and to blackmail Nao. He devised a meticulous plan and issued detailed instructions to his associates Lucrece (his lover), George Brymer (an ex-convict posing as Guy Stallard), and several servants. But things go awry – resulting in Lydia being kidnapped and Ransom murdered – when Carruthers' co-conspirators refuse to act as his chessmen, taking their orders instead (as Hanaud points out) "from their lusts and hates".[2]

Principal characters

edit- Inspector Gabriel Hanaud of the Paris Sûreté

- Julius Ricardo, old friend of Hanaud

- Nahendra Nao, heir to the Maharajah of Chitipur

- Major Harvey Scott Carruthers, secretary to Nahendra Nao

- Elsie Marsh, dancer at the Casino de Paris

- Lydia Flight, young opera singer

- Oliver Ransom, invalided Captain of the Bengal Police

- Lucrece Bouchette, lover of Major Carruthers

- Guy Stallard (George Brymer), blackmailer posing as American millionaire

- Nick Furlong (Mike Budden), chauffeur and ex-convict

Critical reception

editWriting in 1952, Mason's biographer Roger Lancelyn Green reported that many readers considered They Wouldn't Be Chessmen to be the best of all the Hanaud novels, in spite of the fact that the book does not fulfil all the usual rules of a detective story. Green agreed, calling the novel one of Mason's most completely successful books. He particularly praised the "clever and impelling study of conflicting characters built around the striking and original idea of the perfect crime ... going all awry simply because the people concerned were ordinary human beings".[3]

In their A Catalogue of Crime (1989) Barzun and Taylor noted that "Young women abound, one of them (as usual) a ruthless vixen."[4]

References

edit- ^ a b c "British Library Item details". primocat.bl.uk. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Mason, A. E. W (1935). They Wouldn't Be Chessmen. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 291–292.

- ^ Green 1952, p. 213.

- ^ Barzun & Taylor 1989, p. 388.

Bibliography

edit- Green, Roger Lancelyn (1952). A. E. W. Mason. London: Max Parrish.

- Barzun, Jacques; Taylor, Wendall Hertig (1989). A Catalogue of Crime (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-015796-8.

External links

edit- Text of They Wouldn't Be Chessmen at Gutenberg Australia