Sir Thomas de Ercildoun, better remembered as Thomas the Rhymer (fl. c. 1220 – 1298[1]), also known as Thomas Learmont or True Thomas, was a Scottish laird and reputed prophet from Earlston (then called "Erceldoune") in the Borders.[2] Thomas' gift of prophecy is linked to his poetic ability.

Thomas the Rhymer | |

|---|---|

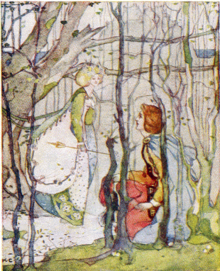

From Thomas the Rhymer (retold by Mary MacGregor, 1908) "Under the Eildon tree Thomas met the lady," illustration by Katherine Cameron | |

| Born | Thomas de Ercildoun c. 1220 Erceldoune (Earlston), Berwickshire, Scotland |

| Died | c. 1298 (age about 78) |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Other names | True Thomas, Thomas Learmouth/Learmonth/Learmount/Learmont/Learmounth, Thomas Rhymer/Rymour/Rymer, Thomas de Erceldoune/Ercildoun, Thomas Rymour de Erceldoune |

| Occupation | Laird |

| Known for | Prophecy |

| Children | Thomas de Ercildounson |

He is often cited as the author of the English Sir Tristrem, a version of the Tristram legend, and some lines in Robert Mannyng's Chronicle may be the source of this association. It is not clear if the name Rhymer was his actual surname or merely a sobriquet.[3]

In literature, he appears as the protagonist in the tale about Thomas the Rhymer carried off by the "Queen of Elfland" and returned having gained the gift of prophecy, as well as the inability to tell a lie. The tale survives in a medieval verse romance in five manuscripts, as well as in the popular ballad "Thomas Rhymer" (Child Ballad number 37).[4][5] The romance occurs as "Thomas off Ersseldoune" in the Lincoln Thornton Manuscript.[6]

The original romance (from c. 1400) was probably condensed into ballad form (c. 1700), though there are dissenting views on this. Walter Scott expanded the ballad into three parts, adding a sequel which incorporated the prophecies ascribed to Thomas, and an epilogue where Thomas is summoned back to Elfland after the appearance of a sign, in the form of the milk-white hart and hind. Numerous prose retellings of the tale of Thomas the Rhymer have been undertaken, and included in fairy tale or folk-tale anthologies; these often incorporate the return to Fairyland episode that Scott reported to have learned from local legend.

Historical figure

editSir Thomas was born in Erceldoune (also spelled Ercildoune – presently Earlston), Berwickshire, sometime in the 13th century, and has a reputation as the author of many prophetic verses. Little is known for certain of his life but two charters from 1260–80 and 1294 mention him, the latter referring to "Thomas de Ercildounson son and heir of Thome Rymour de Ercildoun".[7]

Thomas became known as "True Thomas", supposedly because he could not tell a lie. Popular lore recounts how he prophesied many great events in Scottish history,[7] including the death of Alexander III of Scotland.

Popular esteem of Thomas lived on for centuries after his death, and especially in Scotland, overtook the reputation of all rival prophets including Merlin,[8] whom the 16th century pamphleteer of The Complaynt of Scotland denounced as the author of the prophecy (unity under one king) which the English used as justification for aggression against his countrymen.[8] It became common for fabricated prophecies (or reworkings of earlier prophecies) to be attributed to Thomas to enhance their authority,[8] as seen in collections of prophecies which were printed, the earliest surviving being a chapbook entitled "The Whole Prophecie of Scotland, England, etc." (1603).[8][9][11]

Prophecies attributed to Thomas

editDescriptions and paraphrases of Thomas's prophecies were given by various Scottish historians of yore, though none of them quoted directly from Thomas.[12][a]

- "On the morrow, afore noon, shall blow the greatest wind that ever was heard before in Scotland."[13]

- This prophecy predicted the death of Alexander III in 1286. Thomas gave this prediction to the Earl of Dunbar, but when there was no change in weather patterns discernible at the ninth hour, the Earl sent for the prophet to be reproved. Thomas replied the appointed hour has not come, and shortly thereafter, the news came reporting of the king's death.

- The earliest notice of this prophecy occurs in Bower's 15th-century Scotichronicon, written in Latin.[14][b] An early English vernacular source is John Bellenden's 16th century Croniklis of Scotland, a translation of Hector Boece.[14]

- "Who shal rule the ile of Bretaine / From the North to the South sey?"

- "A French wife shal beare the Son, / Shall rule all Bretaine to the sey,

- that of the Bruces blood shall come / As neere as the nint degree."[15]

- The lines given are structured in the form of one man's questions, answered by another, who goes on to identify himself: "In Erlingstoun, I dwelle at hame/Thomas Rymour men calles me."[16]

- Printed in the aforementioned chapbook The Whole Prophecie of 1603, published upon the death of Elizabeth I, the prophecy purports to have presaged Scottish rule of all of Britain by James I, whose mother Mary Stewart, had been raised in her own mother's native France and was briefly their Queen Consort during her first childless marriage to Francis II.[17]

- This "became in the sequel by far the most famous of all the prophecies,"[18] but it has been argued that this is a rehash of an earlier prophecy that was originally meant for John Stewart, Duke of Albany (d. 1536),[19] whose mother was Anna de la Tour d'Auvergne, daughter of the Count of Auvergne. Words not substantially different are also given in the same printed book, under the preceding section for the prophecy of John of Bridlington,[20] and the additional date clue there "1513 & thrise three there after" facilitating the identification "Duke's son" in question as Duke of Albany, although Murray noted that the Duke's "performance of ... doubty deeds" was something he "utterly failed to do".[21]

Popular folkloric prophecies

editWalter Scott was familiar with rhymes purported to be the Rhymer's prophecies in the local popular tradition, and published several of them.[22] Later Robert Chambers printed additional collected rhyme prophecies ascribed to Thomas, in Popular Rhymes (1826).

- "At Eildon Tree, if yon shall be,

- a brig ower Tweed yon there may see."[23]

- Scott identifies the tree as that on Eildon Hill in Melrose, some five miles away from today's Earlston.[24] Three bridges built across the river were visible from that vantage point in Scott's day.

- "This Thorn-Tree, as lang as it stands,

- Earlstoun sall possess a' her lands."[25]

- or "As long as the Thorn Tree stands / Ercildourne shall keep its lands".[26] This was first of several prophecies attributed to the Rhymer collected by Chambers, who identified the tree in question as one that fell in a storm in either 1814[27] or 1821,[25] presumably on the about the last remaining acre belonging to the town of Earlstoun. The prophecy was lent additional weight at the time, because as it so happened, the merchants of the town had fallen under bankruptcy by a series of "unfortunate circumstances".[28] According to one account, "Rhymer's thorn" was a huge tree growing in the garden of the Black Bull Inn, whose proprietor, named Thin, had its roots cut all around, leaving it vulnerable to the storm that same year.[27]

- "When the Yowes o' Gowrie come to land,

- The Day o' Judgment's near at hand"[29]

- The "Ewes of Gowrie" are two boulders near Invergowrie protruding from the Firth of Tay, said to approach the land at the rate of an inch a year. This couplet was also published by Chambers, though filed under a different locality (Perthshire), and he ventured to guess that the ancient prophecy was "perhaps by Thomas the Rhymer."[29] Barbara Ker Wilson's retold version has altered the rhyme, including the name of the rocks thus: "When the Cows o' Gowrie come to land / The Judgement Day is near at hand."[26]

- the biggest and the bonniest o' a' the three"[30][31]

- Collected from a 72-year-old man resident in Edinburgh.[29]

The Weeping Stones Curse:

- "Fyvie, Fyvie thou'se never thrive,

- lang's there's in thee stanes three :

- There's ane intill the highest tower,

- There's ane intill the ladye's bower,

- There's ane aneath the water-yett,

- And thir three stanes ye'se never get."[32][33]

- Tradition in Aberdeenshire said that Fyvie Castle stood seven years awaiting arrival of "True Tammas," as the Rhymer was called in the local dialect. The Rhymer arrived carrying a storm that brewed all around him, though perfectly calm around his person, and pronounced the above curse. Two of the stones were found, but the third stone of the water-gate eluded discovery.[34] And since 1885 no eldest son has lived to succeed his father.[33]

- "Betide, betide, whate'er betide,

- Haig shall be Haig of Bemerside.[35]

- This prophesied the ancient family of the Haigs of Bemerside will survive for perpetuity. Chambers, in a later editions his Popular Rhymes (1867) prematurely reported that "the prophecy has come to a sad end, for the Haigs of Bemerside have died out."[36][37] In fact, Field Marshal Douglas Haig hails from this family,[38] and was created earl in 1919, currently succeeded by the 3rd Earl (b. 1961).

Ballad

editThe ballad (Roud 219) around the legend of Thomas was catalogued Child Ballad #37 "Thomas the Rymer," by Francis James Child in 1883. Child published three versions, which he labelled A, B and C, but later appended two more variants in Volume 4 of his collection of ballads, published in 1892.[5] Some scholars refer to these as Child's D and E versions.[39] Version A, which is a Mrs Brown's recitation, and C, which is Walter Scott's reworking of it, were together classed as the Brown group by C.E. Nelson, while versions B, D, E are all considered by Nelson to be descendants of an archetype that reduced the romance into ballad form in about 1700, and classed as the 'Greenwood group'. (See §Ballad sources).

Child provided a critical synopsis comparing versions A, B, C in his original publication, and considerations of the D, E versions have been added below.

Ballad synopsis

editThe brief outline of the ballad is that while Thomas is lying outdoors on a slope by a tree in the Erceldoune neighborhood, the queen of Elfland appears to him riding upon a horse and beckons him to come away. When he consents, she shows him three marvels: the road to Heaven, the road to Hell, and the road to her own world (which they follow). After seven years, Thomas is brought back into the mortal realm. Asking for a token by which to remember the queen, he is offered the choice of having powers of harpistry, or else of prophecy, and of these he chooses the latter.

The scene of Thomas's encounter with the elf-queen is "Huntly Bank" and the "Eildon Tree" (versions B, C, and E)[40][41] or "Farnalie" (version D)[c] All these refer to the area of Eildon Hills, in the vicinity of Earlston: Huntly Bank was a slope on the hill and the tree stood there also, as Scott explained:[24][42] Emily B. Lyle was able to localize "farnalie" there as well.[43]

The queen wears a skirt of grass-green silk and a velvet mantle, and is mounted either on a milk-white steed (in Ballad A), or on a dapple-gray horse (B, D, E and R (the Romance)). The horse has nine and fifty bells on each tett (Scots English. "lock of matted hair"[44]) on its mane in A, nine hung on its mane in E, and three bells on either side of the bridle in R, whereas she had nine bells in her hand in D, offered as a prize for his harping and carping (music and storytelling).

Thomas mistakenly addresses her as the "Queen of Heaven" (i.e. the Virgin Mary[45]), which she corrects by identifying herself as "Queen of fair Elfland" (A, C). In other variants, she reticently identifies herself only as "lady of an unco land" (B), or "lady gay" (E), much like the medieval romance. But since the unnamed land of the queen is approached by a path leading neither to Heaven nor Hell, etc., it can be assumed to be "Fairyland," to put it in more modern terminology.[46]

In C and E, the queen dares Thomas to kiss her lips, a corruption of Thomas's embrace in the romance that is lacking in A and B though crucial to a cogent plot, since "it is contact with the fairy that gives her the power to carry her paramour off" according to Child. Absent in the ballads also is the motif of the queen losing her beauty (Loathly lady motif): Child considered that the "ballad is no worse, and the romance would have been much better" without it, "impressive" though it may be, since it did not belong in his opinion to the "proper and original story," which he thought was a blithe tale like that of Ogier the Dane and Morgan le fay.[47] If he chooses to go with her, Thomas is warned he will be unable to return for seven years (A, B, D, E). In the romance the queen's warning is "only for a twelvemonth",[48] but he overstays by more than three (or seven) years.

Then she wheels around her milk-white steed and lets Thomas ride on the crupper behind (A, C), or she rides the dapple-gray while he runs (B, E). He must wade knee-high through a river (B, C, E), exaggerated as an expanse of blood (perhaps "river of blood"), in A.[49] They reach a "garden green," and Thomas wants to pluck a fruit to slake his hunger but the queen interrupts, admonishing him that he will be accursed or damned (A, B, D, E). The language in B suggests this is "the fruit of the Forbidden Tree",[50] and variants D, E call it an apple. The queen provides Thomas with food to sate his hunger.

The queen now tells Thomas to lay his head to rest on her knee (A, B, C), and shows him three marvels ("ferlies three"), which are the road to Hell, the road to Heaven, and the road to her homeland (named Elfland in A). It is the road beyond the meadow or lawn overgrown with lilies[51] that leads to Heaven, except in C where the looks deceive and the lily road leads to Hell, while the thorny road leads to Heaven.

The queen instructs Thomas not to speak to others in Elfland, and to allow her to do all the talking. In the end, he receives as present "a coat of the even cloth, and a pair of shoes of velvet green" (A) or "tongue that can never lie" (B) or both (C). Version E uniquely mentions the Queen's fear that Thomas may be chosen as "teinding unto hell",[5] that is to say, the tithe in the form of humans that Elfland is obliged to pay periodically. In the romance, the Queen explains that the collection of the "fee to hell" draws near, and Thomas must be sent back to earth to spare him from that peril. (See § Literary criticism for further literary analysis.)

Ballad sources

editThe ballad was first printed by Walter Scott (1803), and then by Robert Jamieson (1806).[52][53][54] Both used Mrs Brown's manuscript as the underlying source. Child A is represented by Mrs Brown's MS and Jamieson's published version (with only slight differences in wording). Child C is a composite of Mrs Brown's and another version.[55] In fact, 13 of the 20 stanzas are the same as A, and although Scott claims his version is from a "copy, obtained from a lady residing not far from Ercildoun" corrected using Mrs Brown's MS,[56] Nelson labels the seven different stanzas as something that is "for most part Scott's own, Gothic-romantic invention".[57]

Child B is taken from the second volume of the Campbell manuscripts entitled "Old Scottish Songs, Collected in the Counties of Berwick, Roxburgh, Selkirk & Peebles", dating to ca. 1830.[5][59] The Leyden transcript, or Child "D" was supplied to Walter Scott before his publication, and influenced his composition of the C version to some degree.[58] The text by Mrs Christiana Greenwood, or Child "E" was "sent to Scott in May of 1806 after reading his C version in the Minstrelsey,[58] and was dated by Nelson as an "early to mid-eighteenth-century text".[60] These two versions were provided to Scott and were among his papers at Abbotsford.

Mrs Brown's ballads

editMrs Brown, also known as Anna Gordon or Mrs Brown of Falkland (1747–1810),[61][62] who was both Scott's and Jamieson's source, maintained that she had heard them sung to her as a child.[63] She had learned to sing a repertoire of some three dozen ballads from her aunt, Mrs Farquheson.[d][61][64][62] Mrs Brown's nephew Robert Eden Scott transcribed the music, and the manuscript was available to Scott and others.[62][65] However different accounts have been given, such as "an old maid-servant who had been long as the nursemaid being the one to teach Mrs Brown."[66]

Walter Scott's ballads in three parts

editIn Minstrelsy, Walter Scott published a second part to the ballad out of Thomas's prophecies, and yet a third part describing Thomas's return to Elfland. The third part was based on the legend with which Scott claimed to be familiar, telling that "while Thomas was making merry with his friends in the Tower of Ercildoune," there came news that "a hart and hind... was parading the street of the village." Hearing this, Thomas got up and left, never to be seen again, leaving a popular belief that he had gone to Fairyland but was "one day expected to revisit earth".[56] Murray cites Robert Chambers's suspicion that this may have been a mangled portrayal of a living local personage, and gives his own less marvellous traditional account of Thomas's disappearance, as he had received it from an informant.[67]

In Walter Scott's "Third Part" to the ballad, Thomas finds himself in possession of a "elfin harp he won" in Fairyland in a minstrel competition. This is a departure both from the traditional ballad and from the medieval romance, in which the queen tells Thomas to choose whether "to harpe or carpe," that is, to make a choice either of the gift of music or of the gift of speech. The "hart and hind" is now being sung as being "white as snow on Fairnalie" (Farnalie has been properly identified by Lyle, as discussed above). Some prose retellings incorporate some features derived from this third part (See §Retellings).

Duncan Williamson

editThe traditional singer Duncan Williamson, a Scottish traveller who learned his songs from his family and fellow travellers, had a traditional version of the ballad which he was recorded singing on several occasions. One recording (and discussion of the song) can be heard on the Tobar an Dualchais website.[68]

Medieval romance

editThe surviving medieval romance is a lengthier account which agrees with the content of the ballad.[69]

The romance opens in the first person (migrating to the third),[e] but probably is not genuinely Thomas's own work. Murray dated the authorship to "shortly after 1400, or about a hundred years after Thomas's death",[46] but more recent researchers set the date earlier, to the (late) 14th century. The romance often alludes to "the story," as if there had been a preceding recension, and Child supposed that the "older story," if any such thing actually existed, "must be the work of Thomas".[70]

As in ballad C, Huntley banks is the locale where Thomas made sighting of the elfin lady. The "Eldoune, Eldone tree (Thornton, I, 80, 84)" is also mentioned as in the ballad. Thomas is captivated by her, addressing her as queen of heaven, and she answers she is not so lofty, but hints she is of fairy kind. Thomas propositions her, but she warns him off saying that the slightest sin will undo her beauty. Thomas is undaunted, so she gives the "Mane of Molde" (i.e. Man of Earth; mortal man) (I, 117) consent to marry her and to accompany her.

"Seven tymes by hyr he lay," (I, 124), but she transforms into a hideous hag immediately after lying with him, and declares he shall not see "Medill-erthe" (I,160) for a twelvemonth ("twelmoneth", "xij Mones" vv.152, 159). As in the ballad, the lady points out one way towards heaven and another towards hell during their journey to her dominion (ca.200–220). The lady is followed by greyhounds and "raches" (i.e. scent dogs) (249–50). On arrival, Thomas is entertained with food and dancing, but then the lady tells him he must leave. To Thomas, his sojourn seems to last for only three days, but the lady tells him that three years ("thre ȝere"), or seven years ("seuen ȝere"), have passed (284–6) (the manuscripts vary), and he is brought back to the Elidon tree.

Fytte II is mostly devoted to prophecies. In the opening, Thomas asks for a token by which to remember the queen, and she offers him the choice of becoming a harper or a prophet ("harpe or carpe"). Rather than the "instrumental" gift, Thomas opts for the "vocal (rather oral) accomplishments."[71] Thomas asks her to abide a bit and tell him some ferlys (marvels). She now starts to tell of future battles at Halidon Hill, Bannockburn, etc., which are easily identifiable historic engagements. (These are tabulated by Murray in his introduction.)

The prophecies of battles continue into Fytte III, but the language becomes symbolic. Near the end Thomas asks why Black Agnes of Dunbar (III, 660) imprisoned him, and she predicts her death. This mention of Black Agnes is an anachronism, Thomas of Erceldoune having lived a whole generation before her, and she was presumably confused with an earlier Countess of the March.[72]

Manuscript sources

editThe medieval romance survives complete or in fragments in five manuscripts, the earliest of which is the Lincoln codex compiled by Robert Thornton:[73]

- Thornton MS. (olim. Lincoln A., 1. 17) - ca. 1430–1440.[6]

- MS. Cambridge Ff. 5, 48 - mid 15th century.

- MS. Cotton Vitellius E. x., - late 15th century.

- MS. Landsowne 762 - ca. 1524–30

- MS. Sloane 2578 MSS. - 1547. Lacks first fitt.

All these texts were edited in parallel by J. A. H. Murray in The Romance and Prophecies of Thomas of Erceldoune (1875).[74]

The Cotton MS. gives an "Incipit prophecia Thome Arseldon" and an "Explicit prophetia thome de Arseldoune",[75] thus this was the version that Walter Scott excerpted as Appendix. The Sloane MS. begins the second fytte with: "Heare begynethe þe ijd fytt I saye / of Sir thomas of Arseldon,"[76] and the Thornton MS. gives the "Explicit Thomas Of Erseldowne" after the 700th line.[77]

Relationship between romance and ballad forms

editThe romance dates from the late 14th to the early 15th century (see below), while the ballad texts available do not antedate ca. 1700-1750 at the earliest.[79] While some people believe that the romance gave rise to the ballads (in their existing forms) at a relatively late date, this view is not uncontroversial.

Walter Scott stated that the romance was "the undoubted original", the ballad versions having been corrupted "with changes by oral tradition".[80] Murray flatly dismisses this inference of oral transmission, characterizing the ballad as a modernization by a contemporary versifier.[81] Privately, Scott also held his "suspicion of modern manufacture."[63][82]

C. E. Nelson argued for a common archetype (from which all the ballads derive), composed around the year 1700 by "a literate individual of antiquarian bent" living in Berwickshire.[83] Nelson starts off with a working assumption that the archetype ballad, "a not too remote ancestor of [Mrs] Greenwood['s version]" was "purposefully reduced from the romance".[60] What made his argument convincing was his observation that the romance was actually "printed as late as the seventeenth century"[60] (a printing of 1652 existed, republished Albrecht 1954), a fact missed by several commentators and not noticed in Murray's "Published Texts" section.

The localization of the archetype to Berwickshire is natural because the Greenwood group of ballads (which closely abide by the romance) belong to this area,[84] and because this was the native place of the traditionary hero, Thomas of Erceldoune.[60] Having made his examination, Nelson declared that his assumptions were justified by evidence, deciding in favour of the "eighteenth-century origin and the subsequent tradition of [the ballad of] 'Thomas Rhymer'",[83] a conclusion applicable not only to the Greenwood group of ballads but also to the Brown group. This view is followed by Katharine Mary Briggs's folk-tale dictionary of 1971,[86] and David Fowler.[87]

From the opposite point of view, Child thought that the ballad "must be of considerable age", even though the earliest available to him was datable only to ca. 1700–1750.[79] E. B. Lyle, who has published extensively on Thomas the Rhymer,[88] presents the hypothesis that the ballad had once existed in a very early form upon which the romance was based as its source.[89] One supporter of this view is Helen Cooper who remarks that the ballad "has one of the strongest claims to medieval origins";[90][91] another is Richard Firth Green who has provided strong evidence for his contention that "continuous oral transmission is the only credible explanation," by showing that one detail in the medieval romance, omitted from the seventeenth-century print, is preserved in the Greenwood version.[92][93]

Literary criticism

editIn the romance, the queen declares that Thomas has stayed three years but can remain no longer, because "the foul fiend of Hell will come among the (fairy) folk and fetch his fee" (modernized from Thornton text, vv.289–290). This "fee" "refers to the common belief that the fairies "paid kane" to hell, by the sacrifice of one or more individuals to the devil every seventh year." (The word teind is actually used in the Greenwood variant of Thomas the Rymer: "Ilka seven year, Thomas, / We pay our teindings unto hell, ... I fear, Thomas, it will be yerself".[5]) The situation is akin to the one presented to the title character of "Tam Lin" who is in the company of the Queen of Fairies, but says he fears he will be given up as the tithe (Scots: teind or kane) paid to hell.[94] The common motif has been identified as type F.257 "Tribute taken from fairies by fiend at stated periods"[85] except that while Tam Lin must devise his own rescue, in the case of the Rymer, "the kindly queen of the fairies will not allow Thomas of Erceldoune to be exposed to this peril, and hurries him back to earth the day before the fiend comes for his due".[94] J. R. R. Tolkien also alludes to the "Devil's tithe" as concerns the Rhymer's tale in a passing witty remark[95]

Influences

editIt has been suggested that John Keats's poem La Belle Dame sans Merci borrows motif and structure from the legend of Thomas the Rhymer.[96]

Washington Irving, while visiting Walter Scott, was told the legend of Thomas the Rhymer,[97] and it became one of the sources for Irving's short story Rip van Winkle.[98][99]

Adaptations

editRetellings

editThere have been numerous prose retelling of the ballad or legend.

John Tillotson's version (1863) with "magic harp he had won in Elfland" and Elizabeth W. Greierson's version (1906) with "harp that was fashioned in Fairyland" are couple of examples that incorporate the theme from Scott's Part Three of Thomas vanishing back to Elfland after the sighting of a hart and hind in town.[100][101]

Barbara Ker Wilson's retold tale of "Thomas the Rhymer" is a patchwork of all the traditions accrued around Thomas, including ballad and prophecies both written and popularly held.[102]

Additional, non-exhaustive list of retellings as follows:

- Donald Alexander Macleod (ed.), Arthur George Walker (illus.) "Story of Thomas the Rhymer" (ca. 1880s).[103]

- Gibbings & Co., publishers (1889).[104][105]

- Mary MacGregor (ed.), Katharine Cameron (illus.) (1908).[106]

- Donald Alexander Mackenzie (ed.), John Duncan (illus.), "Story of Thomas the Rhymer" (1917).[107]

- George Douglas (ed.), James Torrance (illus.), in Scottish Fairy Tales (sans date, ca. 1920).[108]

- Judy Paterson (ed.), Sally J. Collins (illus.) (1998).[109]

- In Cencrastus, Issue 79, Winter 2004-05, Donald Smith published a "new narrative adaptation of Ercildoun's version which is much superior to Scott's" that runs to 31 stanzas.

Musical adaptations

edit- The German version of Tom der Reimer by Theodor Fontane was set as a song for male voice and piano by Carl Loewe, his op. 135.

- An outstanding early recording, in German is by Heinrich Schlusnus, on Polydor 67212, of 1938 (78 rpm).

- Modern versions of the "Thomas the Rhymer" ballad include renditions by British folk rock act Steeleye Span which recorded two different versions for their 1974 album Now We Are Six and another for Present--The Very Best of Steeleye Span, released in 2002. Singer Ewan MacColl has also recorded his version of the ballad.

- The English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams left an opera by the title of Thomas the Rhymer incomplete at the time of his death in 1958. The libretto was a collaboration between the composer and his second wife, Ursula Vaughan Williams, and it was based upon the ballads of Thomas the Rhymer and Tam Lin.[110]

- The British country/acid house band Alabama 3 drew upon the ballad of Thomas the Rhymer in a 2003 recording entitled Yellow Rose. Alabama 3's lyrics give the ballad a new setting in the American frontier of the 19th Century, where an enchanting woman lures the narrator to a night of wild debauchery, then robs and finally murders him. Yellow Rose appears on their 2003 album Power in the Blood (One Little Indian / Geffen).

- Kray Van Kirk's Creative Commons-licensed song "The Queen of Elfland", for which Van Kirk also created a music video, retells the story in a modern setting.[111][112]

Thomas in literature and theatre

edit- Rudyard Kipling's poem, "The Last Rhyme of True Thomas" (1894), features Thomas Learmounth and a king who's going to make Thomas his knight.

- John Geddie, Thomas the Rymour and his Rhymes. [With a portrait of the author], Edinburgh: Printed for the Rymour Club and issued from John Knox's House, 1920.

- In William Croft Dickinson's children book The Eildon Tree (1944), two modern children meeting Thomas the Rhymer and travel back in time to a critical point in Scottish history.

- Thomas is one of the main characters of Alexander Reid's play The Lass wi the Muckle Mou (1950).

- Nigel Tranter, Scottish writer authored the novel True Thomas (1981).

- Ellen Kushner's novel Thomas the Rhymer (1990).

- Bruce Glassco's short story "True Thomas", in Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling's anthology Black Swan, White Raven (1997). Like the other stories presented there, the Glassco story put a new spin on the legend.

- "Erceldoune", a novella by Richard Leigh (co-author of Holy Blood, Holy Grail), features a folk-singer named Thomas "Rafe" Erlston. The novella appeared in the collection Erceldoune & Other Stories (2006) ISBN 978-1-4116-9943-4

- In Sergey Lukyanenko's fantasy novel The Last Watch, Thomas is described as having survived until today and currently occupies the post of the Head of the Scottish Night Watch.

- Thomas appears in John Leyland's ballad "Lord Soulis". Here, after failing to bind William II de Soules with magical ropes of sand, he determines that the sorcerer must be wrapped in lead and boiled.[113][114]

- Thomas the Rhymer is a major character in Andrew James Greig's novel "One is One" , (2018),[115] where Thomas is a man lost to himself and to time as he roams Scotland in the present day.

- Fantasy writer Diana Wynne Jones' young adult novel Fire and Hemlock draws from the ballad in a story set in the present day.

- Patricia C. Wrede's novel Snow White and Rose Red (1989), an adaptation of the fairy tale of the same name, casts the bear-prince and his brother as the Queen of Faerie's sons by Thomas Learmont, and a condensed version of his legend is given as backstory; the brother uses the surname "Rimer" in his dealings with mortals.

Representations in fine art

edit- Thomas the Rhymer and the Queen of Faerie (1851), by Joseph Noel Paton illustrated the ballad. A print reproduction by Thomas the Rhymer and the Queen of Faerie by John Le Conte was published W & A K Johnston (1852),.

- Beverly Nichols' A Book of Old Ballads (1934) reprinted the Greenwood version of the ballad, with a print of "Thomas the Rhymer" by H. M. Brock[116]

See also

edit- "Tam Lin", another Child Ballad with fairyland abduction theme

- Queen of Elfland

- Mikhail Lermontov, a Russian poet who, according to family legend, was a descendant of Thomas Learmont as Lermontov (Russian nobility)[117]

Footnotes

editExplanatory notes

edit- ^ Scott undertook creative exercise of writing in verse of his own what Thomas's prophecy might have been: "Thomas the Rhymer: Part Second" by Scott 1803, Minstresy II, pp. 303–307. Scott prefaced his creation with copious notes to fend off "the more severe antiquaries".

- ^ Bower, Scotichronicon Book X, Ch. 43: "...qua ante horam explicite duodecimam audietur tam vehemens ventus in Scotia, quod a magnis retroactis temporibus consimilis minime inveniebatur." (footnoted in Murray 1875, pp. xiii-)

- ^ Or at least "Farnalie" is given as the spot to where the queen returned Thomas in the final stanza of the D version. Child 1892, Pop. Ball. IV, pp. 454–5

- ^ who learned them at the estate of her husband called Allan-a-quoich, by the waterfall of Linn a Quoich, near the source of the River Dee in Braemar, Aberdeenshire

- ^ — or, to be more precise: "The narrative begins in the first person, but changes to the third, lapsing once for a moment into the first" (Burnham 1908, p. 377)

Citations

edit- ^ Tedder, Henry Richard (1889). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 17. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Chambers 1826, p. 73; Chambers 1842, p. 6

- ^ Scott 1803, Minstrelsy, II, p.309. "Robert de Brunne" here is another name for Robert Mannyng. Scott goes on to quote another source from a manuscript in French, but Thomas of "Engleterre" is likely Thomas of Britain.

- ^ Child Ballad #37. "Thomas the Rymer", Child 1884, Pop. Ball. I, pp. 317–329

- ^ a b c d e Child 1892, Pop. Ball. IV, p.454–5

- ^ a b Laing & Small 1885, pp. 82–83, 142–165.

- ^ a b Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, v. 1, p. 317, Dover Publications, New York 1965

- ^ a b c d Murray 1875, p. xxx.

- ^ The Whole prophecie of Scotland, England, and some part of France and Denmark, prophesied by meruellous Merling, Beid, Berlington, Thomas Rymour, Waldhaue, Eltraine, Banester, and Sybilla, all according in one. Containing many strange and meruelous things. Edinburgh: Robert Waldegraue. 1603. (Repr. Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Club 1833; Later edition: Edinburgh: Andro Hart, 1615)

- ^ a b c Murray 1875, Appendix I, p. 48–51

- ^ In The Whole Prophecie (1603), the first three sections are the prophecies of Merlin, Bede, and John of Bridlington (analyzed in Murray 1875, pp. xxx–xl), followed by the prophecy of Thomas the Rhymour (printed in entirety in Appendix).[10]

- ^ "His prophecies are alluded to by Barbour, by Wintoun, and by Henry, the minstrel, or Blind Harry.. None of these authors, however, give the words of any of the Rhymer's vaticinations" (Scott 1803, Minstresy II, pp. 281–2)

- ^ This particular rendition from Latin into English can be found in, e.g.:Watson, Jean L. (1875). The history and scenery of Fife and Kinross. Andrew Elliot.

- ^ a b Murray 1875, p. xiii.

- ^ Whole Prophecie, "The Prophecie of Thomas Rymour" vv.239–244[10]

- ^ vv. 247-8[10]

- ^ Cooper, Helen (2011), Galloway, Andrew (ed.), "Literary reformations of the Middle Ages", The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Culture, Cambridge University Press, pp. 261–, ISBN 9780521856898

- ^ Murray 1875, pp. xxxiv

- ^ Murray 1875, p. xxxiv, citing Lord Hailes, Remarks on the History of Scotland (1773), Chapter III, pp.89–

- ^ "How euer it happen for to fall, / The Lyon shal be Lord of all./The French wife shal beare the sonne, /Shal welde al Bretane to the sea, And from the Bruce's blood shall come. /As near as the ninth degree." (Murray 1875, p. xxxvi)

- ^ Murray 1875, p. xxxv.

- ^ Scott 1803, Minstrelsy II, pp. 300–, "sundry rhymes, passing for his prophetic effusions, are still current among the vulgar"

- ^ Scott 1803, Minstrelsy II, pp. 301–.

- ^ a b Scott 1803, Minstrelsy II, p. 343.

- ^ a b Chambers 1826, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b Wilson 1954, p. 17

- ^ a b Murray 1875, pp. xlix, lxxxv. Murray received detailed report on the tree from Mr James Wood, Galashiels.

- ^ Chambers 1826, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Chambers 1826, p. 96.

- ^ Chambers 1826, p. 81.

- ^ Modernized as: "York was, London is, and Edinburgh shall be / The biggest and bonniest o' the three", Wilson 1954, p. 17

- ^ Chambers 1842, p. 8.

- ^ a b Modern variant "Fyvie, Fyvie thou'll never thrive / As long as there's in thee stones three;/There's one in the oldest tower,/There's one in the lady's bower/There's one in the water-gate,/And these three stones you'll never get." in: Welfare, Simon (1991). Cabinet of Curiosities. John Fairley. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 88. ISBN 0312069197.

- ^ Chambers 1826, p. 8.

- ^ Scott 1803, Minstrelsy II, p. 301.

- ^ Murray 1875, p. xliv.

- ^ Chambers 1870, p. 296.

- ^ Benet, W. C. (April 1919). "Sir Douglas Haig". The Caledonian. 19 (1): 12–14.

- ^ Lyle 2007, p. 10

- ^ Child 1884, Pop. Ball. I, 320.

- ^ Child 1892, Pop. Ball. IV, pp. 454–5.

- ^ "Huntley Bank, a place on the descent of the Eildon Hills," Scott, Walter (1887). Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft. G. Routledge and sons. p. 112.

- ^ She identified it with farnileie on the Eildon Hills, which appears in a document of 1208 about a land dispute "between the monasteries of Melrose and Kelso". Scott had failed to make this identification. (Lyle 1969, p. 66; repr. Lyle 2007, p. 12)

- ^ Tait (sometimes written tate and tett), a lock of matted hair. Mackay's Dictionary (1888); Tate, tait, teat, tatte 2. "Lock, applied to hair" John Jamieson's Dictionary (Abridged, 1867).

- ^ Child (1892), Pop. Ball. I, p. 319.

- ^ a b Murray 1875, p. xxiii

- ^ Child 1884, Pop. Ball. I, p. 320ab, and note §

- ^ Child 1884, Pop. Ball. I, p. 320b

- ^ Child 1884, Pop. Ball. I, p. 321b.

- ^ Child 1884, Pop. Ball. I, 321a, note *

- ^ Leven, "a lawn, an open space between woods"; Lily leven "a lawn overspread with lilies or flowers" John Jamieson's Dict. (Abridged, 1867)

- ^ Scott 1803, Minstrelsy II, pp. 269–273: "Part 1, Ancient" which is prefaced "never before published"

- ^ Jamieson 1806, Vol. II, pp. 7–10: "procured in Scotland... before [he] knew that he was likely to be anticipated in its publication by Mr Scott" (p.7)

- ^ Jamieson and Scott's printed in parallel in Murray 1875, pp. liii–

- ^ Child 1884, Pop. Ball. I, p. 317a "C being compounded of A and another version..."

- ^ a b Scott 1803, Minstrelsy II, p. 268

- ^ Nelson 1966, p. 140

- ^ a b c Nelson 1966, p. 142.

- ^ Nelson adds "at Marchomont House, Berwickshire.[58]

- ^ a b c d e Nelson 1966, p. 143.

- ^ a b Bronson, Bertrand H. (1945). "Mrs. Brown and the Ballad". California Folklore Quarterly. 4 (2): 129–140. doi:10.2307/1495675. JSTOR 149567.

- ^ a b c d Rieuwerts, Sigrid (2011). The Ballad Repertoire of Anna Gordon, Mrs Brown of Falkland. Scottish Text Society. ISBN 978-1897976326.; Reviewed by Julie Henigan in Journal of Folklore Research Reviews and by David Atkinson in Folk Music Journal (Dec 23, 2011)

- ^ a b Letter of Robert Anderson, who compiled The Works of the British Poets, to Bishop Percy, (Murray 1875, p. liii n1), taken from Nicholl's Illustrations of Literature, p.89

- ^ Perry, Ruth (2012). Pollak, Ellen (ed.). Artistic Representation: The Famous Ballads of Anna Gordon, Mrs Brown (pdf). Cultural Histories. Vol. 4. Bloomsbury. pp. 187–208. doi:10.5040/9781350048157-ch-008. hdl:1721.1/69940. ISBN 978-1-3500-4815-7.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Quoting from letter from Thomas Gordon: "In conversation I mentioned them to your Father [i.e. William Tytler], at whose request my Grandson Mr Scott, wrote down a parcel of them as his aunt sung them. Being then but a meer novice in musick, he added in his copy such musical notes as he supposed..."; and later: "The manuscript that was being passed around among Anderson, Percy, Scott, and Jamieson had been penned by Anna Brown's nephew, Robert Scott, who took down the words and music to the ballads as his aunt sung them at William Tytler's request in 1783."Perry 2012, pp. 10–12

- ^ Murray 1875, pp. liii

- ^ Murray 1875, pp. lxix–l.

- ^ "Tobar an Dualchais Kist O Riches". www.tobarandualchais.co.uk. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Richard Utz, "Medieval Philology and Nationalism: The British and German Editors of Thomas of Erceldoune," Florilegium: Journal of the Canadian Society of Medievalists 23.2 (2006), 27–45.

- ^ "als the story sayes" v.83 or "als the storye tellis" v. 123, Child 1884, Pop. Ball. I, 318b

- ^ Murray 1875, p. xlvii.

- ^ Murray 1875, p. lxxxi.

- ^ Murray 1875, pp. lvi–lxi.

- ^ Murray 1875

- ^ Murray 1875, pp. 2, 47

- ^ Murray 1875, p. 18.

- ^ Murray 1875, p. 46.

- ^ Cooper 2005, p. 172 and n5

- ^ a b Child 1884, Pop. Ball. I, 320a, "the earliest version (A) can be traced at furthest only into the first half of the last century. Child's comment in volume 1 did not include the Greenwood text he appendixed in Vol. IV, but Nelson has assigned the same 1700–1750 period ("early to mid-eighteenth-century text") for the Greenwood text.[60] Cooper prefers to push it back to a "text whose origins can be traced back to before 1700"[78]

- ^ Scott 1803, Minstrelsy II, pp. 274-. This commentary comes under Scott's "Appendix to the Thomas the Rhymer", where he prints an excerpt from the romance (the version with an Incipit, i.e. the Cotton MS, as spelled out by Murray in his catalog of "Printed Editions", Murray 1875, p. lxi)

- ^ Scott goes on to say it was "as if the older tale had been regularly and systematically modernized by a poet of the present day", (Scott 1803, Minstrelsy II, p. 274), and Murray, seizing on this statement, comments that "the 'as if' in the last sentence might be safely left out, and that the 'traditional ballad' never grew 'by oral tradition' out of the older, is clear...", Murray 1875, p. liii

- ^ "Dismissed by Ritson as new-fangled and by Scott as inauthentic, Mrs Brown's ballads were considered exemplary by both Robert Jamieson and, later, Francis James Child, who gave her variants pride of place in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads" in Henigan's review of Rieuwerts' book.[62]

- ^ a b Nelson 1966, p. 147.

- ^ Nelson 1966, pp. 142–143.

- ^ a b Briggs, Katherine M. A Dictionary of British Folk-Tales in the English Language Part B: Folk Legends.

- ^ "The various forms of the ballad of True Thomas all seem to be based on the medieval romance, 'Thomas of Ercidoun'"[85]

- ^ Fowler, David C. (1999), Knight, Stephen Thomas (ed.), "Rymes of Robin Hood", Robin Hood: An Anthology of Scholarship and Criticism, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, pp. 73–4, ISBN 0859915255

- ^ Utz 2006 surveys post-1950s scholarship on Thomas.

- ^ Lyle, E. B. (1970). "The Relationship between Thomas the Rhymer and Thomas of Erceldoune". Leeds Studies in English. NS 4: 23–30.

- ^ Cooper, Helen (2005), Saunders, Corinne J. (ed.), "Thomas of Erceldoune: Romance as Prophecy", Cultural Encounters in the Romance of Medieval England (preview), DS Brewer, pp. 171–, ISBN 0191530271

- ^ Cooper, Helen (2004). The English Romance in Time : Transforming Motifs from Geoffrey of Monmouth the Death of Shakespeare (preview). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0191530271., p.467 n17: "[Lyle's paper] suggests that an early form of the ballad may underlie the romance."

- ^ Green, Richard Firth (1997), Gray, Douglas; Cooper, Helen; Mapstone, Sally (eds.), "The Ballad and the Middle Ages", The Long Fifteenth Century: Essays for Douglas Gray, Oxford University Press, p. 168

- ^ Green, Richard Firth (2021). "‘Thomas Rymer’ and Oral Tradition," Notes and Queries, 68, 4.

- ^ a b Child 1884, Pop. Ball. I, p.339a.

- ^ Tolkien refers to this as follows: "The road to fairyland is not the road to Heaven; nor even to Hell, I believe, though some have held that it may lead thither indirectly by the Devil's tithe," and subsequently quoting stanzas of the ballad "Thomas Rymer" beginning ""O see you not yon narrow road/" (text from Jamieson 1806, p. 9). In essay "On Fairy Stories" (orig. pub. 1947), reprinted in p.98 of Tolkien, J.R.R. (2002) [1947], "Tree and Leaf (On Fairy-Stories)", A Tolkien Miscellany, SFBC, pp. 97–145, archived from the original (doc) on 2 April 2015

- ^ Stewart, Susan (2002). Poetry and the Fate of the Senses. University of Chicago Press. p. 126. ISBN 0226774139.

- ^ Irving, Washington (1861). The Crayon Miscellany. G.P. Putnam. pp. 238–240.

- ^ Myers, Andrew B. (1976). A Century of commentary on the works of Washington Irving, 1860–1974 (snippet). Sleepy Hollow Restorations. p. 462. ISBN 9780912882284.

- ^ Humphrey, Richard (1993). Scott: Waverley. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 9780521378888.

- ^ Tillotson, John (1863), "Thomas the Rhymer", The Boy's Yearly Book: being the twelve numbers of the "Boy's Penny Magazine", S. O. Beeton

- ^ Grierson, Elizabeth Wilson (1930) [1906], "Thomas the Rhymer", Tales from Scottish Ballads, Stewart, Allan, 1865-1951, illus., A. & C. Black, pp. 195–213 Project Gutenberg (Children's Tales from Scottish Ballads 1906)

- ^ Wilson, Barbara Ker (1954), "Thomas the Rhymer", Scottish Folk-tales and Legends, Oxford University Press; Repr. Wilson, Barbara Ker (1999) [1954], "Thomas the Rhymer", Fairy Tales from Scotland (Retold by), Oxford University Press, pp. 8–17, ISBN 0192750127

- ^ Macleod, Donald Alexander (1906), "XII. Story of Thomas the Rhymer", A Book of Ballad Stories, Walker, A. G. (Arthur George 1861-1939), illus.; Dowden, Edward, intro., London: Wells, Gardner, Darton, pp. 94–107 (original printing: New York : F.A. Stokes Company, [188-?])

- ^ anonymous (1889), "Thomas the Rhymer", Scottish Fairy Tales, Folklore, and Legends, London: W. W. Gibbings & Co., pp. 93–97

- ^ Reprinted:anonymous (1902), "Thomas the Rhymer", Scottish Fairy Tales, Folklore, and Legends, Strahan, Geoffrey, illus., London: Gibbings & Co., pp. 93–97. Also cf. the first tale "Canobie Dick and Thomas of Ercildoun"

- ^ MacGregor, Mary (1908). Stories from the Ballads Told to the Children. Cameron, Katharine (1874–1965), illus. London: T. C. & E. C. Jack.

- ^ Mackenzie, Donald Alexander (1917), "XII. Story of Thomas the Rhymer", Wonder Tales from Scottish Myth and Legend, Duncan, John, illus., New York: Frederick A Stoke, pp. 147–160

- ^ Douglas, George (c. 1920), "XII. Story of Thomas the Rhymer", Scottish Fairy Tales, Torrance, James, illus., New York: W. Scott Pub. Co., OCLC 34702026

- ^ Paterson, Judy (1998). Thomas the Rhymer, retold by. Collins, Sally J., illus. The Amaising Publishing House Ltd. ISBN 1871512603.

- ^ Ursula Vaughan Williams, R.V.W.: A Biography of Ralph Vaughan Williams (Oxford University Press, 1964), p. 393.

- ^ Van Kirk, Kray, The Queen of Elfland, Lyrics, archived from the original on 27 December 2014, retrieved 27 December 2014

- ^ Van Kirk, Kray, The Queen of Elfland, music video, retrieved 23 October 2015

- ^ John Leyden. "Lord Soulis" (PDF). British Literary Ballads Archive. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ David Ross. "Hermitage Castle". Britain Express. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ Greig, Andrew James (2018). One is One. Independently Published. ISBN 978-1983122088.

- ^ Nichols, Beverley (1934). A Book of Old Ballads. Brock, H. M. (Henry Matthew), 1875–1960, illus. London: Hutchingson & co., ltd.

- ^ Powelstock, David (2011). Becoming Mikhail Lermontov: The Ironies of Romantic Individualism in Nicholas I's Russia. Northwestern University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0810127883.

References

edit- Tedder, Henry Richard (1889). "Erceldoune, Thomas of". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 17. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Texts

- Albrecht, William Price (1954). The loathly lady in "Thomas of Erceldoune"; with a text of the poem printed in 1652. University of New Mexico publications in language and literature; no. 11. University of New Mexico Press. LCCN 55062031.

- — "A seventeenth-century text of Thomas of Erceldoune" (1954), Medium Ævum 23

- Chambers, Robert (1826). The Popular Rhymes of Scotland. W. Hunter. ISBN 9780807822623.

- Chambers, Robert (1842). Popular Rhymes, Fireside Stories, and Amusements of Scotland. William and Robert Chambers. [1]

- Chambers, Robert (1870). The Popular rhymes of Scotland: New Edition. W. & R. Chambers. p. 296.

- Child, Francis James (1884), "37. Thomas Rymer", The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, vol. I, Houghton Mifflin, pp. 317–329

- Child, Francis James (1892), "37. Thomas Rymer", The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, vol. IV, Houghton Mifflin, pp. 454–5

- Jamieson, Robert (1806). Popular Ballads and Songs: From Tradition. Vol. 2. A. Constable and Company. pp. 3–43.: "True Thomas and Queen of Elfland"

- Laing, David; Small, John, eds. (1885), "Thomas off Ersseldoune", Select remains of the ancient popular poetry of Scotland, W. Blackwood and Sons, pp. 82–83, 142–165

- Murray, James A. H., ed. (1875). The Romance and Prophecies of Thomas of Erceldoune: printed from five manuscripts; with illustrations from the prophetic literature of the 15th and 16th centuries. EETS O.S. Vol. 61. London: Trübner.

- Scott, Walter (1803). Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. Vol. II. James Ballantyne. pp. 262–321.: "Thomas the Rhymer in Three Parts"

- Studies

- Burnham, Josephine M. (1908). "A Study of Thomas of Erceldoune". PMLA. 23 (3): 375–. doi:10.2307/456793. JSTOR 456793. S2CID 163171545.

- Lakowski, Romuald I. (2007), Croft, Janet Brennan (ed.), ""Perilously Fair": Titania, Galdriel, and the Fairy Queen of Medieval Romance", Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language, McFarland, pp. 60–78, ISBN 9780786428274

- Lyle, Emily (1967). A Study of 'Thomas the Rhymer' and 'Tam Lin' in Literature and Tradition (Ph.D.). University of Leeds.

- Lyle, Emily (1969). "A Reconsideration of the Place-Names in'Thomas the Rhymer'". Scottish Studies. 13: 65–71.

- Lyle, E. B. (2007). Fairies and Folk: Approaches to the Scottish Ballad Tradition (snippet). Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier. p. 10. ISBN 978-3884769577.

- Nelson, C. E. (1966). "The Origin and Tradition of the Ballad of "Thomas Rhymer"". New Voices in American Studies. Purdue University Press: 138–. ISBN 0911198105.

- Utz, Richard (2006). "Medieval Philology and Nationalism: The British and German Editors of Thomas of Erceldoune". Florilegium. 23 (2): 27–45.

- Dictionary of National Biography