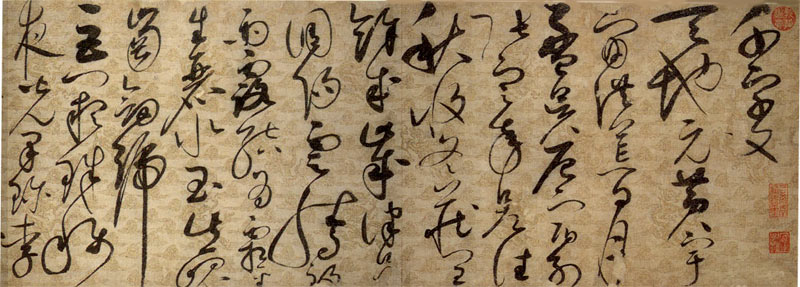

Emperor Hui Zong Zhao Ji's "Thousand Character Classic in Cursive Script" (赵佶草书千字文) scroll is a notable calligraphy purportedly crafted in the fourth year of the Xuanhe era of the Song dynasty (1122 AD). [1] The scroll measures 31.5 centimeters in height and 1172 centimeters in width, crafted on an exclusively made palace paper known as "Yunlong Jinjian" (云龙金笺纸), distinguished by hand-drawn cloud and dragon patterns with gold powder on white hemp paper. The scroll stretches over 10 feet in length without any seams. The back of the calligraphy scroll bears the seal of "Imperial Calligraphy" (御书) and a monogram (花押)[note 1] devised and utilized by Zhao Ji. Currently, it is housed in the Liaoning Provincial Museum.

The texts

editThe "Thousand Character Classic" (千字文), originally titled "The Thousand Character Rhymed Text in Wang Xizhi's Calligraphy (次韵王羲之书千字)," was composed during the Southern and Northern Dynasties period, by Liang dynasty cabinet minister Zhou Xingsi (470-521 AD) under the directive of Emperor Wu of Liang.[2] The emperor tasked the extraction of 1,000 distinct characters from Wang Xizhi's calligraphy oeuvre to create a calligraphy primer for the royal progeny. However, finding these characters disordered and incoherent, he tasked Zhou Xingsi, known for his literary prowess, with composing a rhymed text..[3] Accordingly to historical fiction Taiping Guangji, Zhou Xingsi crafted the verse in a single night and his hair turned grey the next morning.[4] This overnight masterpiece exhibits coherent logic, elegant structure, and numerous references to classic scriptures and historical texts; the language is concise and easy to memorize, making it an exceptional educational aid for children. The "Thousand Character Classic" not only complied with the king's decree but also yielded a masterpiece that has garnered praise for over 1,500 years. It stands as the longest-enduring primer on general characters since the Six dynasties era. It also remains a classic text that calligraphers across generations vie to replicate.

The artist

editEmperor Huizong of Song, Zhao Ji (1082-1135) was the eleventh son of Emperor Shenzong and the younger brother of Emperor Zhezong. When Emperor Zhezong passed away without a son, Empress Xiang designated Zhao Ji as the emperor, making him the eighth emperor of the Northern Song dynasty. Emperor Huizong was renowned as one of the most culturally and artistically talented emperors in Chinese history. He was a celebrated painter and calligrapher, known for his mastery of the "slender gold" (瘦金体, shou jinti) style of calligraphy.[5] His personal seal “亓” "" (天下一人, tianxia yiren), is arguably the most famous monogram in Chinese history. Despite his talents, Emperor Huizong's later years were marred by his favoritism towards corrupt ministers and eunuchs, which contributed to the downfall of the Northern Song dynasty. A supremely talented artist, he tragically ended up as a ruler of a fallen state and was captured by the Jin dynasty, where he passed away in captivity.[6] Yuan dynasty minister and historian Toqto'a remarked in History of Song: "Emperor Huizong was capable of everything except being an emperor!" [7]

The work

editZhao Ji wrote countless volumes of "Thousand Character Classic" throughout his life, but only two copies have survived to this day: one in the Slender Gold style, now housed at Shanghai Museum; the other in the Cursive style, now housed at Liaoning Museum.[1] In his book on painting and calligraphy, Gengzi Xiaoxia Ji (庚子消夏記), Qing dynasty collector and connoisseur Sun Chengze stated that Emperor Huizong's "Thousand Character Classic in cursive script" was inspired by the Tang dynasty calligrapher Huai Su. Calligraphy historians commented that compared with Huai Su, they are really on par with each other.[8] This piece was crafted when Zhao Ji was forty years old. The scroll was exquisitely written in one go on an 11.72-meter-long sheet of cloud-dragon patterned golden paper, with hardly any flawed strokes. It achieves the ultimate in unrestrained, spontaneous and free-flowing writing. The seamless scroll paper is a testament to the advanced papermaking technology of the Northern Song dynasty,[9] and it has been designated a national treasure.

The Chinese Calligraphy and Painting Grading Dictionary (中国书画定级图典) states: "The calligraphy adopts the cursive script method of the Tang dynasty artist Huai Su, but it has already achieved a level of mastery that allows for free and versatile application. The brushwork is both vigorous and smooth. The thin, firm strokes resemble the fine gold and silver inlay techniques found in ancient bronze vessels, hence it is referred to as 'Slender Gold Script.' This characteristic is evident in both regular script and cursive script. Later, this work was included in the collection of the Qing dynasty's imperial household. It bears the imperial collection seals of the Qianlong, Jiaqing, and Xuantong emperors of the Qing dynasty.

In 2012, China's National Cultural Heritage Administration designated this calligraphy piece as a “First-Class National Treasure” and listed it as a cultural relic prohibited from being exhibited abroad. [10]

Reception

editEarly Ming dynasty Tao Zongyi stated in his General Introduction to the History of Calligraphy: "Insight and demeanor are completely natural and free from artificiality; one cannot merely discuss how each stroke is written."[11]

Contemporary calligraphy and painting appraiser Yang Renkai commented: "This scroll of cursive script is very peculiar, with large and small characters naturally interspersed. Some resemble monkeys leaping through tall trees, others like dragons swiftly gliding over the water; some characters are connected together, while others are abruptly separated. Overall, it looks like flowers flying across the sky; viewed in parts, some sections resemble withered pine trees lying on high mountains, others like giant stones falling into deep ravines; some like birds suddenly flying out of the forest, others like startled snakes darting into the grass." He also remarked: "This scroll appears as if each character can come alive. Spanning several zhang in length, it was written in one continuous flow, with hardly a single stroke out of place."[9][6]

Note

editReference

edit- ^ a b "辽宁省博物馆-徽宗赵佶草书千字文". Archived from the original on 2017-07-08. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ^ 周興嗣. (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- ^ 《梁書•列傳第四十三》“自是銅表銘、柵塘碣、北伐檄、次韻王羲之書千字,並使興嗣為文,每奏,高祖輒稱善,加賜金帛。”

- ^ 《太平廣記》:「梁周興嗣編次千字文,而有王右軍者,人皆不曉。其始乃梁武教諸王書,令殷鐵石於大王書中,榻一千字不重者,每字片紙,雜碎無序。武帝召興嗣謂曰:"卿有才思,爲我韻之。"興嗣一夕編綴進上,鬢髮皆白,而賞錫甚厚。」

- ^ "宋徽宗赵佶—两宋辽金书法-书法空间——永不落幕的书法博物馆". www.9610.com. Retrieved 2024-05-20.

- ^ a b "宋徽宗赵佶:站在中国历史大拐点的帝王艺术家_南方艺术". www.zgnfys.com. 2018-09-21. Retrieved 2024-05-20.

- ^ 脫脫. (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- ^ "赵佶《草书千字文》赏析- - 书法字典". www.shufazidian.com. Retrieved 2024-05-20.

- ^ a b 杨, 仁恺 (1962). "略谈宋徽宗《草书千字文》及其它". www.9610.com. Retrieved 2024-05-20.

- ^ "关于发布《第二批禁止出国(境)展览文物目录(书画类)》的通知". 国家文物局. 文物博函〔2012〕1345号. Archived from the original on 2019-12-19. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ^ 陶宗儀. (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.