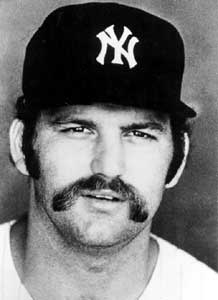

Thurman Lee Munson (June 7, 1947 – August 2, 1979) was an American professional baseball catcher who played 11 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) with the New York Yankees, from 1969 until his death in 1979. A seven-time All-Star, Munson had a career batting average of .292 with 113 home runs and 701 runs batted in (RBIs). Known for his outstanding fielding, he won the Gold Glove Award in three consecutive years (1973–75).

| Thurman Munson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Catcher | |

| Born: June 7, 1947 Akron, Ohio, U.S. | |

| Died: August 2, 1979 (aged 32) Green, Ohio, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| August 8, 1969, for the New York Yankees | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| August 1, 1979, for the New York Yankees | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .292 |

| Home runs | 113 |

| Runs batted in | 701 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Born in Akron, Ohio, Munson was selected as the fourth pick of the 1968 MLB draft and was named as the catcher on the 1968 College Baseball All-American Team. Munson hit over .300 in his two seasons in the minor leagues, establishing himself as a top prospect. He became the Yankees' starting catcher late in the 1969 season, and after his first complete season in 1970, in which he batted .302, he was voted American League (AL) Rookie of the Year. Considered the "heart and soul" of the Yankees, Munson was named captain of the Yankees in 1976, the team's first since Lou Gehrig. That same year, he won the AL Most Valuable Player (MVP) Award.

As captain, Munson helped lead the Yankees to three consecutive World Series appearances from 1976 to 1978, winning championships in the latter two years. He is the first player in baseball history to be named a College Baseball All-American and then in MLB win a Rookie of the Year Award, MVP Award, Gold Glove Award, and World Series championship. He is also the only catcher in MLB postseason history to record at least a .300+ batting average (.357), 20 RBIs (22), and 20 defensive caught stealings (24).

On August 2, 1979, Munson died in a crash while practicing landings in his aircraft at Akron–Canton Airport.[1][2][3] The Yankees honored him by immediately retiring his uniform 15,[4] and dedicating a plaque to him in Monument Park.

Early life

editThurman Lee Munson was born on June 7, 1947, in Akron, Ohio, to Darrell Vernon Munson and Ruth Myrna Smylie, and he was the youngest of four children.[5] His father was a World War II veteran who became a truck driver while his mother was a homemaker.[6] When he turned eight, the Munson family moved to nearby Canton.[7] He was taught how to play baseball by his older brother Duane, and usually played baseball with kids Duane's age, who were four years older.[8] His brother left to join the United States Air Force while Thurman was a freshman in high school.[6]

Munson attended Lehman High School, where he was captain of the football, basketball, and baseball teams and was all-city and -state in all three sports.[9] He played halfback in football, guard in basketball, and mostly shortstop in baseball.[10] Munson switched to catcher in his senior year in order to handle the pitching prowess of his teammate, Jerome Pruett (a fifth-round draft pick of the St. Louis Cardinals in 1965 who never reached the majors).[11]

College career

editMunson attracted scholarship offers from various colleges, and opted to attend nearby Kent State University on scholarship, where he was a teammate of pitcher and broadcaster Steve Stone.

In the summer of 1967, Munson joined the Cape Cod Baseball League, where he led the Chatham A's to their first league title with a prodigious .420 batting average. In recognition of this achievement and his subsequent professional achievements, the Thurman Munson Batting Award is given each season to the league's batting champion.[12] In 2000, Munson was named a member of the inaugural class of the Cape Cod Baseball League Hall of Fame.[13]

Professional career

editDraft and minor leagues

editMunson was selected by the Yankees with the fourth overall pick in the 1968 Major League Baseball draft. In his only full minor league season, he batted .301 with six home runs and 37 runs batted in (RBIs) for the Binghamton Triplets in their final season (1968), and made his first appearance in Yankee Stadium in August 1968, when the Triplets came to play an exhibition game against the Yankees.[14] He was batting .363 for the Syracuse Chiefs in 1969 when he earned a promotion to the New York Yankees.

New York Yankees (1969–1979)

editMunson made his major league debut on August 8, 1969, in the second game of a doubleheader against the Oakland Athletics.[15] Munson went two for three with a walk, one RBI and two runs scored. Two days later, his first major league home run was the second of three consecutive home runs hit by the Yankees off Lew Krausse Jr. in a 5-1 Yankee victory over the A's.[16] For the season, Munson batted .256 with one home run and nine RBIs. He made 97 plate appearances, but drew ten walks and had one sacrifice fly, which gave him 86 official at bats, and allowed him to go into the 1970 season still technically a rookie.

The Yankees used the pair of Jake Gibbs and Frank Fernández at catcher for most of 1969. During the off season, the Yankees dealt Fernández to the A's. Munson responded by batting .302 with seven home runs and 57 RBIs, and making 80 assists en route to receiving the 1970 American League Rookie of the Year award.

1971–1974

editMunson received his first of seven All-Star nods in 1971, catching the last two innings without an at-bat.[17] An outstanding fielder, Munson committed only one error all season. It occurred on June 18 against the Baltimore Orioles when opposing catcher Andy Etchebarren knocked Munson unconscious on a play at the plate, dislodging the ball.[18] He also only allowed nine passed balls all season and caught 36 of a potential 59 base stealers for a 61% caught stealing percentage.

Munson was known for his longstanding feud with Boston Red Sox counterpart Carlton Fisk.[19][20] He would always be irritated at comments praising Boston's catcher.[19] One particular incident that typified their feud, and the Yankees – Red Sox rivalry in general, occurred on August 1, 1973 at Fenway Park. With the score tied at 2–2 in the top of the ninth and runners on first and third, Munson attempted to score from third on Gene Michael's missed bunt attempt.

As Red Sox pitcher John Curtis let his first pitch go, Munson broke for the plate. Michael tried to bunt, and missed. With Munson coming, Fisk elbowed the Yankee shortstop out of the way and braced for Munson, who barreled into Fisk. Fisk held onto the ball, but Munson remained tangled with Fisk as Felipe Alou, who was on first, attempted to advance. The confrontation at the plate triggered a ten-minute bench-clearing brawl in which both catchers were ejected.[21] "The Fisk-Munson rivalry was at the core of the Yankees-Red Sox tension of that era," wrote sportswriter Moss Klein.[19]

Munson made his second All-Star team and won his first of three straight Gold Glove Awards in 1973. He also emerged as more of a slugger for the Yankees, batting .300 for the first time since 1970, and hitting a career high 20 home runs. In 1974, Munson was elected to start his first of three consecutive All-Star games, going one for three with a walk and a run scored.[22]

1975–1976

editOn June 24, 1975, during a game against the Baltimore Orioles, Munson had an altercation with Mike Torrez. Torrez hit Munson with a pitch in the first inning, gave up a single to him in the fourth, and threw a pitch up by his head in the sixth. When Munson came to bat in the eighth, umpire Nick Bremigan warned Torrez not to throw any more brushback pitches; this time, Torrez blew kisses to Munson. The benches cleared, but no punches were thrown; however, after Munson grounded out to end the at-bat, he charged the pitcher's mound.[23] Munson batted a career high .318 in 1975, which was third in the league behind Rod Carew and Fred Lynn. For the start of the 1976 season, Munson was named the first Yankees team captain since Lou Gehrig retired in 1939. He responded by batting .302 with 17 home runs and 105 RBIs to receive the American League MVP Award and lead the Yankees to their first World Series appearance since 1964. He batted .435 with three RBIs and three runs scored in the American League Championship Series against the Kansas City Royals, and batted .529 with two RBIs and two runs scored in the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. Already down three games to none, Munson went four for four in the final game of the Series at Yankee Stadium, but New York was swept by the "Big Red Machine." Combined with the hits he got in his final two at bats in game three, his six consecutive hits tied a World Series record set by Goose Goslin of the Washington Senators in 1924.

Reds catcher Johnny Bench was named the World Series MVP in 1976. A fairly obvious comparison of opposing backstops was made to Reds manager Sparky Anderson during the post-World Series press conference, to which Anderson responded, "Munson is an outstanding ballplayer and he would hit .300 in the National League, but you don't ever compare anybody to Johnny Bench. Don't never embarrass nobody by comparing them to Johnny Bench." Visibly upset by these comments, which he heard as he entered the room, Munson "ripped into Anderson," according to sportswriter Moss Klein.[24][19]

1977–1979

editOver the 1976 offseason, Munson encouraged Steinbrenner to sign free agent slugger Reggie Jackson. "Go out and get the big man," Munson said. "He can carry a team like nobody else."[19] The two struggled to get along, however, especially after Jackson did an interview with Sport magazine in late May. In the interview, Jackson claimed that he was "the straw who stirs the drink" and also stated "Munson thinks he can be the straw that stirs the drink, but he can only stir it bad."[19] When Jackson sent backup catcher Fran Healy to apologize for those remarks, insisting he was misquoted, Munson responded, "For four bleeping pages?!"[19] Ill feelings persisted for much of the year between the two men, but they eventually came to respect one another late in the year, recognizing each other's talent and importance to the team.[19]

Munson batted .308 with 100 RBIs in 1977, giving him three consecutive seasons batting .300 or better with 100 or more RBIs each year. He was the first catcher to accomplish the feat in three consecutive years since Yankee Hall of Famer Bill Dickey's four straight seasons from 1936-1939, matched only by Mike Piazza since (1996–2000). The Yankees repeated as American League Champions, and faced the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series. Munson batted .320 with a home run and three RBIs in the Yankees four games to two victory over the Dodgers. The Dodgers had stolen 114 bases during the regular season, yet Munson caught four of six potential base stealers in the first four games of the series to keep the speedy Dodgers grounded in the final two.

In 1978, the Yankees and Royals faced each other for the third consecutive time in the ALCS. Tied at a game apiece, and trailing 5–4 in the bottom of the eighth inning of game three, Munson hit the longest home run of his career, a 475-foot (145 m) shot off Doug Bird over Yankee Stadium's Monument Park in left-center field, to give the Yankees a 6–5 win.[25] They won the pennant the next day, and went on to beat the Dodgers again in the World Series in six games, winning the final four. Munson batted .320 (8-for-25) with seven RBIs in this Series and also caught Ron Cey's foul pop-up for the final out.

Munson's World Series championships in 1977 and 1978 made him only the second catcher in baseball history, after Johnny Bench, to win a Rookie of the Year Award, an MVP Award, a Gold Glove Award, and a World Series title during his career. Subsequently, Buster Posey became the third catcher to win all four awards. Munson and Posey, both named as college baseball All-Americans, are the only two catchers named to an All-American team who also own a ROY, MVP, GG, and World Series title.

The Yankees had lost three in a row, and were in fourth place, eleven games behind the Baltimore Orioles in the American League East heading into the All-Star break in 1979. Despite a .288 average, the wear-and-tear of catching was beginning to take its toll on Munson, and he was overlooked for the American League All-Star team. Frequently homesick, he had been asking for a trade to the Cleveland Indians since 1977 in order to be closer to his family in Canton.[19][26] Munson was also considering retiring at the end of the season. At the end of July, the Yankees were still in fourth place at 57–48 (.543), fourteen games behind Baltimore.[27]

Death

editIn August 1979, Munson had been flying airplanes for over a year and purchased a Cessna Citation I/SP jet with a Yankee blue interior so he could fly home to his family in Canton on off-days.[19][28][29] It was his fourth airplane in less than a year and a half. His flight instructor Dave Hall spoke well of his ability: "From the onset to completion of training Mr. Munson displayed well above average skills and judgment as a pilot."[28] However, in a 2022 tribute piece for his Countdown with Keith Olbermann podcast, sports commentator Keith Olbermann recalled that four months before Munson's death, he was told that Yankee executives were terrified Munson was "not as good a pilot as he thinks he is" and that they were attempting to get owner George Steinbrenner to trade him to Cleveland to get him to stop flying, afraid that he might "wind up killing himself."[30]

On the afternoon of August 2, 1979, Munson was practicing takeoffs and landings at the Akron-Canton Regional Airport with Hall and friend Jerry Anderson, with whom he had formed a real estate partnership.[28][1][2][31] Shortly after 3:40 p.m. EDT, Munson had received clearance for takeoff and three touch-and-go landings on Runway 23, which were completed.[32]

While on approach for the fourth and final landing on a different runway (19), Munson did not extend the flaps and allowed the aircraft to sink too low before increasing engine power, causing the jet to clip a tree and fall short of the runway. The plane then hit a tree stump and burst into flames,[33] on Greensburg Road, 870 feet (265 m) short of runway 19.[32][34][28]

Hall and Anderson both survived the accident. Hall received burns on his arms and hands, and Anderson received burns on his face, arm and neck. Munson, however, was in a more precarious position. Unable to move due to what was originally thought to be the wrecked fuselage of the plane pinning him against his seat, Munson was trapped and Hall and Anderson were unable to free him in the only attempt they were able to make before flames engulfed the cockpit. Munson died of asphyxiation due to the inhalation of superheated air and toxic substances.[32] Later it was revealed that Munson had suffered a cervical fracture on impact which resulted in paralysis, rendering him unable to move.[35]

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation into the crash stated that the probable cause was "the pilot's failure to recognize the need for, and to take action to maintain, sufficient airspeed to prevent a stall into the ground during an attempted landing. The pilot also failed to recognize the need for timely and sufficient power application to prevent the stall during an approach conducted inadvertently without flaps extended. Contributing to the pilot's inability to recognize the problem and to take proper action was his failure to use the appropriate checklist and his nonstandard pattern procedures which resulted in an abnormal approach profile." Munson was not wearing the available shoulder harness restraint, only a lap belt, which contributed to the severity of his injuries.[32] Anderson credited Munson for remaining at the controls with saving his life. "Thurman flew that airplane to the last nanosecond. He kept it under control and brought us down. He never panicked. He saved our lives."[28]

On August 1, 1980, the day before the first anniversary of the accident, the Yankees filed a $4.5-million lawsuit against Cessna Aircraft Co. and Flight Safety International, Inc. (the company who was training Munson to fly), with team spokesman John J. McCarty saying "we asked for $4.5 million because that is what Munson would be worth if the Yankees traded him." That lawsuit was dismissed before it went to trial.[36] Munson's widow, Diana, also filed a $42.2 million wrongful death lawsuit against the two companies. Cessna offered Munson a special deal on flying lessons if he would take them from FlightSafety International. Rather than requiring Munson to take a two-week safety class in Kansas, FlightSafety assigned a "traveling instructor" to go on the road with him, and train him between ballgames.[37] The lawsuit was eventually settled out of court.[citation needed]

Legacy

editThe day after his death, before the start of the Yankees' four-game set with the Baltimore Orioles in the Bronx, the team paid tribute to their deceased captain in a pre-game ceremony in which the starters stood at their defensive positions, save for the catcher's box, which remained empty. Following a prayer by Cardinal Terence Cooke, a moment of silence and "America the Beautiful" by Robert Merrill, the fans (announced attendance 51,151) burst into an eight-minute standing ovation.[4] Catcher Jerry Narron, who replaced Munson behind the plate that night,[31] remained in the dugout and did not enter the field until stadium announcer Bob Sheppard said, "And now it is time to play ball. Thank you, ladies and gentlemen, for your co-operation."

On August 6, the entire Yankee team attended Munson's funeral in Canton. Teammates Lou Piniella and Bobby Murcer, who were Munson's best friends, gave eulogies at the gathering of 700 at the Canton Memorial Civic Center.[38][39] That night, before a national viewing audience on ABC's Monday Night Baseball, the Yankees beat the Orioles 5–4 in New York, with Murcer driving in all five runs with a three-run home run in the seventh inning and a two-run single in the bottom of the ninth.[40][41]

Piniella said Munson was "the greatest competitor I've ever seen."[28] Tommy John said, "He was the main reason I came to New York. He was an excellent catcher who called an outstanding game."[42] John also praised him for his leadership, writing that while Jackson led the team when it came to hitting and talking with the press, "in the locker room we looked to Munson."[42]

Yankee owner George Steinbrenner retired Munson's number 15 immediately upon his catcher's death.[4] On September 20, 1980, a plaque dedicated to Munson's memory was placed in Monument Park. The plaque bears excerpts from an inscription composed by Steinbrenner and flashed on the stadium scoreboard the day after his death:

Our captain and leader has not left us, today, tomorrow, this year, next ... Our endeavors will reflect our love and admiration for him.

The locker that Munson used, along with a bronzed set of his catching equipment, was donated to the Baseball Hall of Fame. Despite a packed clubhouse, Munson's final locker position was never reassigned. The locker next to Yankee team captain Derek Jeter's, with Munson's number 15 on it, remained unused as a tribute to the Yankees' lost catcher in the original Yankee Stadium until the Stadium closed in 2008.[28] Munson's locker was moved in one piece to the New Yankee Stadium. It is located in the New York Yankees Museum. Visitors can view the Yankees Museum on game days from when the gates open to the end of the eighth inning and during Yankee Stadium tours. Munson's number 15 is also displayed on the center-field wall at Thurman Munson Stadium, a minor-league ballpark in Canton.

A modest, one-block street at Concourse Village East and 156th Street in The Bronx was named Thurman Munson Way in 1979. Two school buildings, which house several schools including Henry Lou Gehrig Junior High School, have since been built on the street.[43]

The area in Connecticut between Boston and New York City, has been referred to as the "Munson–Nixon line", a play on the Mason–Dixon line, after Munson and former Red Sox player Trot Nixon.[44][45] Steve Rushin, who coined the term in a 2003 Sports Illustrated article, has pinpointed the line as running north of New Haven, south of Hartford, and along the width of central Connecticut.[46][47]

Actor Erik Jensen portrayed Munson in the 2007 ESPN produced mini-series The Bronx Is Burning.

Munson was included on the 2020 Modern Era Hall of Fame Ballot.

Personal life

editIn September 1968, Munson married Diana Dominick at St. John's Church in Canton. The couple had been childhood sweethearts; Diana was already signing her name "Mrs. Thurman Munson" back in sixth grade.[28] They had three children: daughter Tracy, daughter Kelly and son Michael.[48][28] At Game 3 of the 1997 World Series in Cleveland, Diana threw out the ceremonial first pitch. Michael also played baseball professionally, spending three years in the Yankees' organization and one year in Double-A for the Giants. "It felt like I was competing against a ghost, because I didn't know if he would've been proud of what I'd done," Michael said of his career. "Nothing people said affected me, and the comparisons didn't affect me, because the pressure I put on myself was more than any pressure other people put on me."[28]

Munson also enjoyed handball, which he often played at the Canton YMCA. Frogs legs were one of his favorite foods, and he also liked chocolate. He also smoked cigars.[28]

Munson gave Yankee teammate Reggie Jackson his famous nickname "Mr. October".[49]

Baseball accomplishments

editMunson had a career .357 batting average in the postseason with three home runs, 22 RBIs and 19 runs scored. His batting average in the World Series was .373. Munson threw out 44.48% of base runners who tried stealing a base on him, ranking him 11th on the all-time list.[50]

- 1st all time – Singles in World Series, 9

- 10th all time – Batting average by catcher, .292

- 11th all time – Postseason batting average, .357

- 11th all time – Caught stealing percentage

- 16th all time – On base percentage by catcher

- 20th all time – OPS by catcher

- 24th all time – Slugging by catcher

- 26th all time – Hits by catcher

- 26th all time – Runs by catcher

- AL Rookie of the Year (1970)

- AL MVP (1976)

- 3× Gold Glove Award

- 3 AL Pennants

- 2 World Series titles

- 7× All Star

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Munson dies in plane crash". Chicago Tribune. August 3, 1979. p. 1, sec. 5.

- ^ a b "Yankees' star Munson is killed in plane crash". Toledo Blade. (Ohio). Associated Press. August 3, 1979. p. 1.

- ^ "'New love' claims life of Yanks' Munson". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. August 3, 1979. p. 33.

- ^ a b c Bock, Hal (August 4, 1979). "Yankees, O's, fans in Munson tribute". Youngstown Vindicator. (Ohio). Associated Press. p. 13.

- ^ Appel (2009), p. 12

- ^ a b Appel (2009), p. 15

- ^ Appel (2009), p. 13

- ^ Appel (2009), p. 16

- ^ Appel (2009), p. 26

- ^ Appel (2009), p. 27

- ^ Appel (2009), p. 29

- ^ "Cape Cod Baseball League Thurman Munson Award Winners". Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ^ "Hall of Fame Ceremony 20 January 2001". capecodbaseball.org. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Appel (2009), pp. 7–8

- ^ "New York Yankees 5, Oakland A's 0". Baseball-Reference.com. August 8, 1969.

- ^ "New York Yankees 5, Oakland A's 1". Baseball-Reference.com. August 10, 1969.

- ^ "1971 All-Star Game". Baseball-Reference.com. July 13, 1971.

- ^ "Baltimore Orioles 6, New York Yankees 4". Baseball-Reference.com. June 18, 1971.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Klein, Moss (August 1, 2009). "Catcher Thurman Munson, The Captain, was heart and soul of the NY Yankees". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "The Munson/Fisk Rivalry". Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ^ "Boston Red Sox 3, New York Yankees 2". Baseball-Reference.com. August 1, 1973.

- ^ "1974 All-Star Game". Baseball-Reference.com. July 23, 1974.

- ^ Iber, Jorge (2016). Mike Torrez: A Baseball Biography. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-7864-9632-7.

- ^ All Roads Lead to October (chapter 10) by Maury Allen, St. Martin's Press 2000 ISBN 0-312-26175-6

- ^ "1978 American League Championship Series Game Three". Baseball-Reference.com. October 6, 1978.

- ^ Keenan, Jimmy; Russo, Frank. "Thurman Munson". SABR. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "Major loop standings". Youngstown Vindicator. (Ohio). August 1, 1979. p. 33.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Coffey, Wayne (August 1, 2009). "25 years later, Thurman Munson's last words remain a symbol of his life". New York Daily News. (originally from 2004). Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- ^ Lauck, Dan (August 6, 1979). "Munson relative says plane a problem from start". Toledo Blade. (Ohio). p. 16.

- ^ Keith Olbermann (August 2, 2022). "Episode 2: Countdown with Keith Olbermann 8.2.22". Countdown with Keith Olbermann (Podcast). iHeartRadio. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Brennan, Sean (August 1, 2009). "Jerry Narron recalls night he replaced Thurman Munson for Yankees". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on September 9, 2009. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Thurman L Munson, Cessna Citation, 501 N15NY, August 2, 1979" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. (Aircraft Accident Report). April 16, 1980.

- ^ All Roads Lead to October (chapter 10) by Maury Allen, St. Martin's Press 2000 ISBN 0-312-26175-6, reprinted at "last entry for the ThurmanMunson.com history page". Archived from the original on February 2, 2007. Retrieved February 2, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ newsnet5.com, Tom Livingston (August 2, 2012). "Video Vault: 1979 Akron-Canton Airport plane crash killed Thurman Munson". Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Coroner: Paralyzed Munson couldn't escape".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Waldstein, David (August 1, 2018). "Documents Shed Light on the Life and Death of Thurman Munson". The New York Times. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Haitch, Richard (May 2, 1982). "Follow-Up on the News; Munson Case". The New York Times. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ "Munson eulogized by Yankee teammates". Chicago Tribune. August 7, 1979. p. 1, sec.4.

- ^ "Munson's son a hit at funeral". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. August 7, 1979. p. 19.

- ^ "Murcer delivers a tribute". Chicago Tribune. August 7, 1979. p. 1, sec.4.

- ^ "New York Yankees 5, Baltimore Orioles 4". Baseball-Reference.com. August 6, 1979.

- ^ a b John, Tommy; Valenti, Dan (1991). TJ: My Twenty-Six Years in Baseball. New York: Bantam. p. 203. ISBN 0-553-07184-X.

- ^ "Paltry Tribute to a Yankee Lost Too Soon" by Sam Dolnick, The New York Times, April 16, 2010 (p. CT1 April 18, 2010 NY ed.). Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ "A State Divided: Connecticut Town Sits On 'Munson-Nixon' Line Separating Yankees, Red Sox Fandom - CBS New York". www.cbsnews.com. October 5, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ Putterman, Alex; Courant, Hartford (October 4, 2018). "Red Sox-Yankees ALDS Matchup Heightens Tension Along Connecticut's Disputed Dividing Line". Hartford Courant. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ Dickey, Jack (September 19, 2018). "Meet the town evenly divided between Yankees and Red Sox fans". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ Giratikanon, Tom; Katz, Josh; Leonhardt, David; Quealy, Kevin (April 24, 2014). "Up Close on Baseball's Borders". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ "Diana Munson & Goose Gossage at Modell's Grand Central" on YouTube by Katherine Hart, YouTube network video interview, August 06, 2008. News outlets sometimes spell the name Diane, including the NYTimes; however, since "Diana" is used in a recorded face-to-face video interview situation here, the editor has brought all references to that spelling. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (October 4, 2018). "The Burden of Being Mr. October". The New York Times.

- ^ 100 Best Catcher CS% Totals at The Encyclopedia of Baseball Catchers

Bibliography

edit- Appel, Marty (2009). Munson: the Life and Death of a Yankee Captain. New York: Doubleday Books. ISBN 978-0-385-52231-1.

External links

edit- Career statistics from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

- Thurman Munson's Decade of Unmatched Excellence - The Case for His Induction into Baseball's Hall of Fame Archived 2017-08-25 at the Wayback Machine

- NTSB Aircraft Accident Report – probable cause investigation report on Munson's plane crash

- Thurman Munson Archived 2010-04-09 at the Wayback Machine at The Deadball Era