The Gettysburg Battlefield is the area of the July 1–3, 1863, military engagements of the Battle of Gettysburg in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Locations of military engagements extend from the 4-acre (1.6 ha) site of the first shot[G 1] at Knoxlyn Ridge[1] on the west of the borough, to East Cavalry Field on the east. A military engagement prior to the battle was conducted at the Gettysburg Railroad trestle over Rock Creek, which was burned on June 27.[2]

| Gettysburg Battlefield | |

|---|---|

The Battle of Gettysburg, which took place in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania between July 1 and July 3, 1863 | |

| Type | Battlefield |

| Location | Adams County, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 39°48′41″N 77°13′33″W / 39.81139°N 77.22583°W |

| Owner | private, federal |

| Website | Park Home (NPS.gov) |

Geography

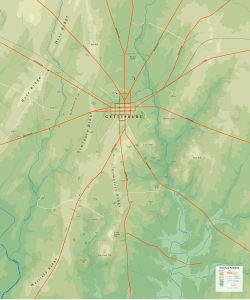

editWithin 10 miles (16 km) of the Maryland/Pennsylvania state line, the Gettysburg battlefield is situated in the Gettysburg-Newark Basin of the Pennsylvania Piedmont entirely within the Potomac River Watershed near the Marsh and Rock creeks' triple point, with the Susquehanna River Watershed (near Oak Hill) occupying an area 3.33 by 5.33 miles (5.4 km × 8.6 km). Military engagements occurred within and around the borough of Gettysburg (1863 pop. 2,400), which remains the population center for the battlefield area at the intersections of roads that connect the borough with 10 nearby Pennsylvania and Maryland towns (e.g., antebellum turnpikes to Chambersburg, York, and Baltimore.)

Topography

editThe battle began on the west at Lohr's, Whistler's, School-House,[3] and Knoxlyn ridges between Cashtown and Gettysburg. Nearer to Gettysburg, dismounted Union cavalry defended McPherson's Ridge and Herr's Ridge, and eventually infantry support arrived to defend Seminary Ridge at the borough's west side. Oak Ridge, a northward extension of both McPherson Ridge and Seminary Ridge, is capped by Oak Hill, a site for artillery that commanded a good area north of the town. Prior to Pickett's Charge, "159 guns stretching in a long line from the Peach Orchard to Oak Hill were to open simultaneously".[4]

Directly south of the town is the gently-sloped Cemetery Hill named for the 1854 Evergreen Cemetery on its crest and where the 1863 Gettysburg Address dedicated the Gettysburg National Cemetery. Eastward are Culp's Hill and Steven's Knoll. Cemetery Hill and Culp's Hill were subjected to assaults throughout the battle by Richard S. Ewell's Second Corps. Cemetery Ridge extends about 1-mile (1.6 km) south from Cemetery Hill.[5]

Southward from Cemetery Hill is Cemetery Ridge of only about 40 feet (12 m) above the surrounding terrain. The ridge includes The Angle's stone wall and the copse of trees at the High-water mark of the Confederacy during Pickett's Charge. The southern end of Cemetery Ridge is Weikert Hill, north of Little Round Top.[6]

The two highest battlefield points are at Round Top to the south with the higher round summit of Big Round Top, the lower oval summit of Little Round Top, and a saddle between. The Round Tops are rugged and strewn with large boulders; as is Devil's Den to the west. [Big] Round Top, known also to locals of the time as Sugar Loaf, is 116 feet (35 m) higher than its Little companion. Its steep slopes are heavily wooded, which made it unsuitable for siting artillery without a large effort to climb the heights with horse-drawn guns and clear lines of fire; Little Round Top was unwooded, but its steep and rocky form made it difficult to deploy artillery in mass. However, Cemetery Hill was an excellent site for artillery, commanding all of the Union lines on Cemetery Ridge and the approaches to them. Little Round Top and Devil's Den were key locations for General John Bell Hood's division in Longstreet's assault during the second day of battle, July 2, 1863. The Plum Run Valley between Houck's Ridge and the Round Tops earned the name Valley of Death on that day.

Borough areas of military engagements

editThe area of the military engagements during the battle included the majority of the 1863 town area[7] and the current borough area. The broadest regions of borough military engagements are the combat area of the Union retreat while being pursued on July 1, as well as the burg's area over which artillery rounds were fired. Confederate artillery fired from Oak Hill southeastward onto the retreated Union line extending east-to-west from Culp's Hill to the west side of Cemetery Hill,[when?] and Union artillery on Cemetery Hill fired on the railway cut (including Wiedrich's battery ~5 pm).[8] Smaller engagements in the town included those with some federals remaining in/near structures after the retreat (e.g., wounded soldiers not willing to surrender). The largest engagement within the current borough was at Coster Avenue (north of the 1863 town) in which Early's division defeated Coster's brigade. The town was generally held by the Confederate provost and used by snipers after the dawn of July 2 (e.g., a brickyard behind the McCreary House,[7]: 282 the John Rupp Tannery on Baltimore St,[9][10] and a church belfry).[11] A Confederate skirmish line at Breckenridge Street faced Federals on Cemetery Hill,[G 2] and ~7 pm July 1, "the Confederate line of battle had been formed on East and West Middle Streets".[12]

History

editAt the close of the battle, some of the ~22,000 wounded remained on the battlefield and were subsequently treated at the outlying Camp Letterman hospital or nearby field hospitals, houses, churches, and other buildings.[N 1] Dead soldiers on the battlefield totaled 8,900; and contractors such as David Warren[G 3]: 8 were hired to bury men and animals (the majority near where they fell). Samuel Weaver oversaw all of these reburials. The first excursion train arrived with battlefield visitors on July 5.[13]

On July 10, Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin visited Gettysburg and expressed the state's interest in finding the fallen veterans a resting place. Attorney David Wills arranged for the purchase of 17 acres (6.9 ha) of Cemetery Hill battlefield land for a cemetery. On August 14, 1863, attorney David McConaughy recommended a preservation association to sell membership stock for battlefield fundraising.[14] By September 16, 1863, battlefield protection had begun with McConaughy's purchase of "the heights of Cemetery Hill and" Little Round Top,[15] and his total purchased area of 600 acres (240 ha) included Culp's Hill land.

On November 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln delivered his Gettysburg Address at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery, which was completed in March 1864 with the last of 3,512 Union reburied. From 1870 to 1873, upon the initiative of the Ladies Memorial Associations of Richmond, Raleigh, Savannah, and Charleston, 3,320 bodies were disinterred and sent to cemeteries in those cities for reburial, 2,935 being interred in Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond. Seventy-three bodies were reburied in home cemeteries. The cemetery was transferred to the United States government May 1872,[16] and the last Battle of Gettysburg body was reburied in the national cemetery after being discovered in 1997.[17]

Union Gettysburg veteran Emmor Cope was detailed to annotate the battlefield's troop positions[18] and his "Map of the Battlefield of Gettysburg from the original survey made August to October, 1863" was displayed at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition.[19] Also in 1863, John B. Bachelder escorted convalescing officers at Gettysburg to identify battlefield locations[20] (during the next winter he interviewed Union officers about Gettysburg).

Memorial association era

edit Gettysburg Battlefield events | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1860 — – 1870 — – 1880 — – 1890 — – 1900 — – 1910 — – 1920 — – 1930 — – 1940 — – 1950 — – 1960 — – 1970 — – 1980 — – 1990 — – 2000 — – 2010 — – |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Antebellum events: 1835 Penn RR cut 1832 Lutheran Old Dorm 1812 Chambersburg Pike 1780 Gettysburg settled 1761 Gettys Tavern -----Color Key----- administration: 1933: NPS

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1864 Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA) added to McConaughy's land holdings and operated a wooden observation tower on East Cemetery Hill from 1878 to 1895.[21][G 4] Post-war, John Bachelder invited over 1,000 officers, including 49 generals, to revisit the field with him.[20] Bachelder also produced a battlefield survey with 1880 federal funds (initiated by Senator Wade Hampton III, a Confederate general). The GBMA approved and disapproved various monuments and in 1888 planted trees at Zeigler's Grove. The 1st battlefield monument was an 1867 marble urn in the National Cemetery dedicated to the 1st Minnesota Infantry, and the 1st memorial outside of the cemetery was the 1878 Strong Vincent tablet Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine on Little Round Top.[3]: 210 By May 1887 there were 90 regimental and battery monuments on the battlefield,[22] and the first bronze monument on the battlefield was Reynolds' 1872 statue in the cemetery.[23] The only two Confederate monuments inside the Union areas of battle held are an 1887 plaque near The Angle commemorating Gen Armistead's farthest advance on July 3 and the 1884 2nd Maryland Infantry monument on Culp's Hill.

The battlefield was used by the 1884 Camp Gettysburg and other summer encampments of the PA National Guard. Commercial development in the 19th century included the 1884 Round Top Branch of railroad to Round Top, Pennsylvania, and after March 1892, Tipton Park operated in the Slaughter Pen[24]—which was at a trolley station of the Gettysburg Electric Railway that operated from 1894 to 1916.

The federal Gettysburg National Park Commission was established on March 3, 1893;[25] after which Congressman Daniel Sickles initiated a May 31, 1894, resolution “to acquire by purchase (or by condemnation) … such lands, or interests in lands, upon or in the vicinity of said battle field.[26] The memorial association era[N 2] ended in 1895 when the[N 3] "Sickles Gettysburg Park Bill" (28 Stat. 651) designated the Gettysburg National Military Park (GNMP) under the War Department.[G 5] Subsequent battlefield improvements included the October 1895 construction of the War Department's observation towers to replace the 1878 Cemetery Hill tower and an 1881 Big Round Top tower.[27]

Commemorative era

editFor payment of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association's debts of $1960.46, on February 4, 1896, the War Department acquired 124 GBMA tracts totaling 522 acres (211 ha),[28] including 320 monuments and about 17 miles (27 km) of roads.[29] Commercial development after Tipton Park was abolished in the fall of 1901 included the July 1902 Hudson Park picnic grove north of Little Round Top[30] (including a boxing arena).[31] A dancing pavilion was erected at the Round Top Museum in 1902,[G 6] and in the saddle area between the Round Tops, David Weikert operated an eating house moved from Tipton Park after it was seized in 1901 by eminent domain.[G 7] Landscape preservation began in 1883 when peach trees were planted in the Peach Orchard,[32] and 20,000 battlefield trees were planted in 1906[33]: '06 (trees are periodically removed from battlefield areas that had been logged prior to the battle.)

Battlefield visitors through the early 20th century typically arrived by train at the borough's 1884 Gettysburg & Harrisburg RR Station[G 8] or the 1859 Gettysburg Railroad Station and used horse-drawn jitneys to tour the battlefield. The borough licensed automobile taxis first in 1913,[34] and the War Department expanded the battlefield roads throughout the commemorative era. Early 20th century battlefield excursions included those by "The Hod Carriers Consolidated Union of Baltimore"[35] and the annual "Topton Day" autumn foliage tours from near Berks County, Pennsylvania.[36]

Veterans reunions included the 1888 25th battle anniversary, a 1906 ceremony to return Gen Armistead's sword to the South.[37] and 53,407 civil war veterans attending the 1913 Gettysburg reunion for the 50th anniversary.[38] The battlefield had a 1912 airfield at Camp Stuart and a WWI Tank Corps center at Brevet Lt. Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower's 1918 Camp Colt, and excursions to the Round Top Park brought alcohol and prostitution.[39] The 1922 Camp Harding included a Marine Corps reenactment of Pickett's Charge observed by President Warren Harding and a next-day simulation of the same attack with modern weapons and tactics.[G 9]

The battlefield's commemorative era[N 2] ended in 1927,[N 3] and use of the national park for military camps continued under an 1896 federal law (29 Stat. 120), e.g., a 1928 artillery and cavalry camp was held at Culp's Hill in conjunction with President Calvin Coolidge's Memorial Day address in the cemetery's rostrum.

Development era

editIn 1933, administration of the GNMP transferred to the 1916 National Park Service (NPS), which initiated Great Depression projects including 1933 Civil Works Administration improvements,[40] and two Civilian Conservation Corps camps were subsequently built for battlefield maintenance and construction projects. After a 1933 comfort station had been built at The Pennsylvania State Memorial,[33]: '33 similar stone Parkitecture structures were built (the west ranger station was completed May 21, 1937),[G 10] and in April 1938, the Works Progress Administration added battlefield parking areas.[41] Numerous commercial facilities were also developed on private battlefield land, particularly during the 1950s "Golden Age of Capitalism" in the United States (e.g., motels, eateries, & visitor attractions).

The battlefield's 2nd largest monument, the Eternal Light Peace Memorial, was accepted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and unveiled at the 1938 Gettysburg reunion that attracted over 300,000 battlefield visitors. In 1939, the 1st of the Gettysburg National Museum's 14 expansions was completed (the electric map auditorium was added in 1963 and closed April 13, 2008).[42] Pitzer Woods was the site of the World War II Camp Sharpe, and McMillan Woods had a German POW camp (the latter was used for post-war housing of migrant workers for local production). Heads-of-state at the battlefield included a 1943 Winston Churchill auto tour with President Roosevelt,[43] President Eisenhower escorting President Charles De Gaulle (1960), and President Jimmy Carter hosting President Anwar Sadat and Prime Minister Menachem Begin (1978).[44]

The 1956 Mission 66 plan for the 1966 NPS 50th anniversary included restoring battlefield houses, resurfacing 31 miles (50 km) of avenues, replacing the railway cut bridge,[45] and restoring the 1884 Gettysburg Cyclorama.

1962–present

editAs the Mission 66 Cyclorama Building at Gettysburg with a new battlefield observation deck was being completed in 1962, the nearby 1896 Zeigler's Grove observation tower was removed (the 1895 Big Round Top observation tower was removed in 1968). In 1967, the NPS purchased the 1921 Gettysburg National Museum,[G 11] which the NPS operated from 1971[46]-2008.[42] Also in 1971, the NPS acquired Round Top Station and the Round Top Museum, using the latter as an environmental resource center[G 12] until demolished c. July 1982.[G 13] The private Gettysburg National Tower of 393 ft (120 m) was completed in 1974 to provide several observation levels for viewing the battlefield, but was purchased under eminent domain and demolished in 2000. In the Devil's Den area, trees were removed in 2007,[47] and the comfort station was razed April 8, 2010.[48] Similarly, the Gettysburg National Museum was demolished in 2008.

In 2008, the Gettysburg National Military Park had 1,320 monuments, 410 cannon, 148 historic buildings, 2½ observation towers, and 41 miles (66 km) of avenues, roads, and lanes;[G 14] (8 unpaved).[49] "one of the largest collections of outdoor sculpture in the world."[50]

In February 2013 the landmark modernist Cyclorama Building and Visitor Center, designed by renowned architect Richard Neutra, was destroyed. The 19th century Gettysburg Cyclorama depicting the battlefield had previously been removed for restoration, and was reinstalled in the new rustic style Gettysburg Museum and Visitor Center.

The Gettysburg National Military Park receives an annual 3 million visitors per year.[51]

The American Battlefield Trust and its partners have acquired and preserved 1,231 acres (4.98 km2) of the overall battlefield in more than 35 separate transactions since 1997.[52] Some of the land has been sold or conveyed to the National Park Service to be incorporated into the national park, but other land acquisitions are outside the official, federally established, current park boundary and thus cannot become part of the park. This includes the headquarters of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, one of the Trust's most significant and expensive acquisitions.[53] In 2015, the Trust paid $6 million for a four-acre parcel that included the stone house that Lee used as his headquarters during the battle. The Trust razed a motel, restaurant and other buildings within the parcel to restore the site to its wartime appearance, added interpretive signs and opened the site to the public in October, 2016.[54]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Another Reunion on the Battlefield" (Google News Archive). Gettysburg Compiler. June 21, 1882. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

About 6 a. m. July 1st, … as the leading regiment … started to cross [Marsh Creek bridge] Lieutenant [M. E.] Jones said "Hold on, I want the honor of firing the gun. … Capt. Callahan, of Pegram's Texas battery, which fired the first [artillery] shot in the battle from Lohr's hill, west of Marsh Creek

- ^ "Voices of Gettysburg: Sarah Broadhead". Archived from the original on 2011-09-01. Retrieved 2015-09-25.

- ^ a b Vanderslice, John M (1897), Gettysburg: A History of the Gettysburg Battle-field Memorial Association With An Account of the Battle…, Philadelphia: Gettysburg Battle Memorial Association (commissioned 1895), p. 210, archived from the original on 2011-07-26, retrieved 2011-02-10,

Marye's Virginia artillery, posted on Lohr's Hill, opened fire ... artillery had kep up a fire successively from Lohr's, Whistler's, and School-House Ridges. … Devin's brigade had its hands full. The enemy advanced upon it by four roads, and on each was checked until the infantry arrived to relieve it.

- ^ Coddington, Edwin B (1968). The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command (Google Books). New York: Scribner's. p. 462. ISBN 0-684-84569-5. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

159 guns stretching in a long line from the Peach Orchard to Oak Hill were to open simultaneously

- ^ Ballard, Ted; Arthur, Billy (1999). "Gettysburg Staff Ride Briefing Book" (PDF). Carlisle, Pennsylvania: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 42908450. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ^ Inners, Jon D.; et al. (2006). Rifts, Diabase, and the Topographic "Fishhook": Terrain … of the Battle of Gettysburg (PDF) (Report). Pennsylvania Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2012. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- ^ a b Trudeau, Noah Andre (14 September 2010). Gettysburg: Test of Courage. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780062045522. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- ^ Gottfried, Bradley M. (2008). The Artillery of Gettysburg. Cumberland House. ISBN 9781581826234. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Gettysburg Foundation: Rupp House". Archived from the original on 2011-02-07.

- ^ Nasby, Dolly (2008). Gettysburg (Google Books). Arcadia. p. 15. ISBN 9780738557687. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ^ Cleaves, Freeman (1960). Meade of Gettysburg. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806122984. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Daniel Skelly and "A Boy's Experiences During the Battle of Gettysburg"". Archived from the original on 2006-12-30.

- ^ Cleaves, Freeman (1960). Meade at Gettysburg (Google books). University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806122984. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

The first battlefield excursion train from Harrisburg arrived promptly on Sunday, July 5.

- ^ "Gettysburg Times - Google News Archive Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "More Exempts from the Draft". The Baltimore Sun. September 16, 1863. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

Cemetery Hill and the granite spur of Round Top … purchased by Mr. D. McConaughy

- ^ Bartlett, John Russell (1874). "The Soldiers' National Cemetery at Gettysburg". google.com. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Google News". google.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Reed, Charles Wellington (2000). Campbell, Eric A (ed.). A Grand Terrible Dramma (Google Books). Fordham Univ Press. ISBN 0-8232-1971-2. ISSN 1089-8719. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ^ "The Exhibit to Worlds Fair" (Google News Archive). Gettysburg Compiler. March 30, 1904. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ a b Hampton, Wade (March 17, 1880). Report of U.S. Senate Military Affairs Committee (Report).

- ^ "Gettysburg Times - Google News Archive Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "NEW-YORK AT GETTYSBURG" (PDF). The New York Times. 11 June 1888. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Unrau, Harlan D (1991), Administrative History of Gettysburg National Military Park and Gettysburg National Cemetery, Pennsylvania (PDF), Denver: National Park Service, OCLC 24228617, archived from the original (2005 NPS Butowski pdf) on 2012-10-20 also at Google books

- ^ "Tipton Boundary Marker; (documented 2004)". National Park Service. 1892. (structure ID MN807, LCS ID 080808) List of Classified Structures: GETT p. 41. Archived from the original on 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

approximately, 7"x7"x1'. Inscribed "T" on top of marker. … rough granite with a "T" inscribed on the top. … at a corner of Tipton land purchased in March 1892 as part of the Tipton Park and photographic studio.

NOTE: The federal survey to determine the extent of the railway was initiated in 1893. Archived 2012-09-15 at the Wayback Machine - ^ "Gettysburg National Military Park Marker" (HMdb.org webpage for marker 14520). War Department. 1908. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2011-02-08. (NPS webpage, MN508) Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hessler, James. "Dan Sickles: The Battlefield Preservationist". Civil War Trust. Archived from the original on 2011-09-18. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

incorporated the Gettysburg Electric Railway Company in 1892

- ^ "New Observatory" (Google News Archive). The Star and Sentinel. July 20, 1881. p. 3, col. 3. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ Battlefield Memorial Association (February 4, 1896), Deed [to United States of America]; recorded June 25, Adams County Courthouse, Deed Book XX

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Gettysburg Compiler - Google News Archive Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "We Have Another Park" (Google News Archives). The Star and Sentinel. July 2, 1902. p. 3. col. 5. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2011-02-06.

The Electric Railway Company, under the superintendency of H. J. Gintling, is busily engaged preparing for encampment week, and the work of putting in new machinery is progressing rapidly.

(p. 3. col. 1) - ^ "Dr. E. D. Hudson Succumbs to Heart Attack" (Google News Archives). The Star and Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ^ "Gettysburg Compiler - Google News Archive Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ a b "The Gettysburg Commission Reports" (transcribed versions: 1893–1921, 1927–1933). Gettysburg Discussion Group. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2010-02-04. (original formats: 1895, 1896, 1897, 1989, 1901, 1902 Archived 2023-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, 1909, 1913, 1918)

- ^ "Gettysburg Times - Google News Archive Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Gettysburg Times - Google News Archive Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Adams County News - Google News Archive Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Frazier, John W (1906). Reunion of the Blue and Gray: Philadelphia Brigade and Pickett's Division (Google Books). Philadelphia: Ware Bros, Company, Printers. Retrieved 2011-02-06.

- ^ Beitler, Lewis Eugene, ed. (December 31, 1913). Report of the Pennsylvania Commission (Google Books) (Report). Harrisburg, PA: Wm. Stanley Bay (state printer). Retrieved 2011-02-06.

- ^ [inspecting officer's findings] (Report). 1918.

This Round Top Park area is frequented by prostitutes … from Gettysburg [and via] excursions from the neighboring towns… These excursions bring in … beer and whiskey which they give or sell to the soldiers. … On a single evening over 50 couples were detected and driven from hiding places behind the tablets, monuments, rocks and trees of the reservation.

- ^ "Re-employment Office Set Up" (Google News Archives). New Oxford Item. November 20, 1933. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ "Gettysburg Area to Be Renovated for Reunion" (Google News Archive). Lawrence Journal-World. April 18, 1938. Archived from the original on 2023-02-24. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

…a $25,000 "face-lifting" for the reunion of the Blue and the Gray. A corps of WPA workers will start possibly this week to obliterate abandoned roadways, reconstruct those now in use, develop parking areas and repaint signs and fences.

— "$52,200 Civil Works Project Approved Here". December 1, 1933. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-03-15. - ^ a b "homepage". SaveTheElectricMap.com. Archived from the original on 2011-01-28. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ "Gettysburg Times - Google News Archive Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "President Jimmy Carter at Gettysburg Part 2: Licensed Battlefield Guide Bob Prosperi". Gettysburg Daily. 30 October 2009. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Gettysburg Times - Google News Archive Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Huntington, Tom (Spring–Summer 2008). "Gettysburg Redux". American Heritage; History News. 38 (4). Archived from the original on 2009-09-16. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ^ "Gettysburg Times - Google News Archive Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Restrooms On Gettysburg Battlefield Demolished". WGAL. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ http://www.nps.gov/archive/gett/gettplan/gettdocuments/DIST2bpi_gett_final.pdf [dead link]

- ^ "Monument Preservation". Preserve Gettysburg. GettysburgFoundation.org. Archived from the original on 2011-02-05. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

- ^ "Gettysburg prepares for tourist spike during 150th anniversary". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ [1] Archived 2019-08-12 at the Wayback Machine American Battlefield Trust "Saved Land" webpage. Accessed November 23, 2021.

- ^ [2] Archived 2020-09-30 at the Wayback Machine Evening Sun, Hanover, Pa., Oct. 24, 2014. Accessed May 30, 2018.

- ^ [3] Archived 2018-07-08 at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post, "Lee's Gettysburg headquarters restored, set to open Oct. 28." Accessed May 24, 2018.

- G. "Archives" (Google News Archive). Gettysburg Times. Times and News Publishing Company. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ Roth, Jeffrey B (September 7, 1988). "Boundary study draft report for Battlefield now complete". Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

four acres, the site of the first shot of the opening battle at Gettysburg, which stands next to U.S. Route 30 and the Whistler house

&

Storrick, William C (December 17, 1936). "Who Fired the First Shot At Battle of Gettysburg". Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-03-16. - ^ "Heritage Sites Walking Tour". June 28, 2002. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

14. … Confederate … skirmish line along Breckenridge Street facing … Federal[s] … on Cemetery Hill.

- ^ "Care of wounded after Battle of Gettysburg & Reburial of Union dead in National Cemetery". July 14, 1986. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ^ "Demise Of 1st Tower Is Located". August 7, 1971. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-03-13. (Gettysburg Compiler of July 30, 1895 ) Archived December 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Gettysburg National Military Park Established By Sickles, Bill Passed In February 1895". February 10, 1970. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ^ "Local Miscellany". Out of the Past: Twenty-Five Years Ago. May 25, 1927. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- ^ "Local Miscellany". Out of the Past: Twenty-Five Years Ago. August 9, 1927. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ^ "The Gettysburg & Harrisburg railroad station". February 8, 1988. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ Weaver, William G (November 13, 1967). "Reminisces Of Gettysburg". Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- ^ "1 of 2 Entrance Stations Opens For Public Use". May 21, 1937. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-02-19. — "Plan $50,000 Battlefield Project Here". July 16, 1934. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

- ^ "Pickett Spur New Addition To Park Relic Collection". April 2, 1975. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ "Nature Study Areas Are Set For Park Here". December 28, 1971. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-01-26. — "Two Special Park Walks This Summer". July 5, 1973. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ^ De Blasi, Nancy (June 11, 1982). "Draft of park plan will be printed soon". Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ^ Latschar, John A (GNMP Superintendent) (April 7, 2009). "Facilities' closings explained". As our readers see it. Archived from the original on 2023-06-29. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- N. "National Park Service". (NPS.gov).

- ^ "Camp Letterman General Hospital". Voices of Battle. 1864. Archived from the original on 2011-04-03. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

Union dead in the camp [Letterman] graveyard were removed to the Soldiers National Cemetery in [from which] southern remains were exhumed between 1872 and 1873 for relocation to southern cemeteries.

- ^ a b Musselman, Curt (2001). Gettysburg's Codori Farm Lane Project (PDF) (Report). p. 1. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- ^ a b …Historians Peer Review of the Process Developed by GNMP …. General Management Plan 1999 History (Report). NPS.gov. March 1998. Archived from the original on 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

1927 - The end of the era of battlefield administration by veterans. 1927 marks the death of Supt. Emmor B. Cope.

| External images | |

|---|---|

| GettysburgPhotographs.com | |

| Battlefield and 145th Reenactment | |

| Tipton stereoviews | |

| Library of Congress maps | |

| GDG.org map room |