Twana (Twana: təwəʔduq)[2] is the collective name for a group of nine Coast Salish peoples in the northern-mid Puget Sound region. The Skokomish are the main surviving group and self-identify as the Twana today. The spoken language, also named Twana, is part of the Central Coast Salish language group. The Twana language is closely related to Lushootseed.[3]

təwəʔduq | |

|---|---|

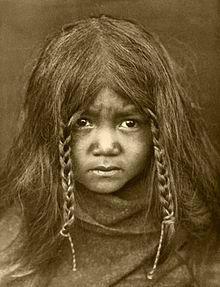

Portrait of a Quilcene boy, c. 1913 | |

| Total population | |

| 796[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Hood Canal, Washington | |

| Languages | |

| Twana, English | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional tribal religion, Christianity, incl. syncretic forms | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Coast Salish peoples |

The nine groups making up the Twana are the Dabop, Quilcene, Dosewallips, Duckabush, Hoodsport, Skokomish, Vance Creek, Tahuya, and Duhlelap.[4] By 1860 there were 33 settlements in total, with the Skokomish making up the majority of the population.[5][6] Most descendants of all groups now are citizens of the Skokomish Indian Tribe and live on the Skokomish Indian Reservation at Skokomish, Washington.[7]

History

editAncestral origins of the Twana include the Proto-Salish people of the northwest Americas who migrated into Washington and split into 23 distinct tribes, each speaking its own language.[3] American contact with the Twana likely began around 1788 when traders participating in the Maritime Fur Trade came looking for sea otter pelts in the Pacific Northwest.[8] The trade was so extensive that the sea otter population was almost diminished by 1792, and there was subsequently little non-native contact in the region for about 30 years.[9] The Twana along with dozens of nearby tribes then experienced the ceding of their land with a series of treaties, starting with the Oregon Treaty (1846) and later the Washington Territory (1853).[10][9] American settlers began moving onto the lands alongside the Twana and other tribes for a short period of time until the Treaty of Point No Point in 1855, which required all Native Americans to migrate off their lands and into reservations within one year after it was passed.[9][11]

Divisions

editThe 9 groups who make up the Twana were historically completely autonomous and independent. The Twana were bound by no higher political power, but only by shared language, location, and cultural practices. While the area in the immediate vicinity of a group's village would be exclusive use, the vast majority of land was used freely by all Twana groups.[12]

| Twana Name | English Name | Meaning | Village location(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| čttaʔbuxʷ | Dabob | Long Spit people | Long Spit (tabuxʷ), at the head of Dabob Bay |

| sqʷul̕sidəbəš | Quilcene | People of the saltwater | The mouth of Donovan Creek (qʷul̕sid) |

| čtduswaylupš | Dosewallips | Dosewallips River people | The mouth of the Dosewallips River (duswaylupš) |

| čtduxʷyabus | Duckabush | Duckabush River people | The mouth of the Duckabush River (duxʷyabus) |

| čtslal̕aɬlaɬtəbəxʷ | Hoodsport | Slahal-country people | The mouth of Finch Creek (slal̕aɬlaɬtəbəxʷ) |

| squqəʔbəš | Skokomish | People of the river |

|

| čtq̓ʷəlq̓ʷili | Vance Creek | Cedar trees people | Up Vance Creek (q̓ʷəlq̓ʷili) at the prairies |

| čttax̌uya | Tahuya | The mouth of Tahuya Bay (tax̌uya) | |

| čxʷlələp | Duhlelap | People at the far end of the canal | The mouth of Mission Creek (duxʷk̓uk̓ʷabš) at Belfair State Park |

Society

editPre-contact and reservation era

editNative Americans of the Coast Salish region resided in semi-permanent villages, usually moving between summer and winter locations over the course of the year in accordance with fishing and crop seasons. Winter locations consisted of permanent plank houses and summer locations held temporary tent-style dwellings. Permanent villages could include homes, sweat houses, and potlatch houses. Twana chiefs had their own speaker that delivered speeches to the villagers. There were individuals who made morning calls to wake up the village as well. Status and wealth was divided among social classes.[9]

The Twana Tribe’s primary resources were salmon (pink, coho, chum/dog, chinook, sockeye), cedar, and redwood.[3][9] Other sources of food and material included herring, smelt, seals, sea otters, blacktail deer, black bear, elk, shellfish, fowl, and plant species such as bracken, camus, and wapato. Roots, berries, and nuts were also gathered in the region. Hides and shredded cedar bark were used to make aprons, skirts, breechclouts, shirts, leggings, robes, and moccasins.[9]

There were likely connections within the Twana tribes as well as with other tribal groups in the southern Coast Salish region. This included trade between other Salish groups, especially with those more inland for items that could not be found at the coast.[3] Some items from the east included mountain goat hair and hemp fiber. Canoes were sourced from the western outer coast tribes. Fishing and hunting grounds could be shared among groups. Twana were not known to partake in violent conflict, however shamans had the ability to harm other groups if needed. Coast Salish conflict was generally defensive in nature.[9]

Men and women had different roles within the Twana village. Wood carving was a primary craft practiced by men. Woodwork included planks, houses, canoes, utensils, and containers such as bent-corner boxes. Similarly, men carved bone, stone, and antler. Wealthy and high-status men included chiefs and potlatch sponsors. Women were known to wear leg and chin tattoos. Women's roles included gathering roots, berries, and nuts, and well as making baskets, cordage, mats, and blankets. Materials for such crafts included shredded cedar bark, sedge, cattail leaves. Twana women were to isolate during their menstrual periods, the first of which signaled a woman's eligibility for marriage. Marriage was arranged by families and could be between members of different villages.[9]

Customs and ceremonies

editTwana beliefs include the heart and life souls that occupy each person, the loss of one being associated with illness and death, respectively. Deities include the sun and earth. Shamans held power to cause or cure illness, restore lost souls, and even cause death. Illness held certain significance among Twana culture. Illness could be a signal of soul loss or possession of a spirit. Young aspiring shamans, inheriting the shamanistic spirit or acquiring it through quests, became ill once the spirit possessed their body.[9] The concept of the circle is also of deep importance within Twana culture, including among modern-day Twana. The cyclical nature of the circle is connected to many aspects of Twana life, such as the seasons, the moon and sun, the horizons, and gatherings where group members sit in a circle.[13]

Ceremonies included the winter dance, soul recovery, elaborately painting boards, and Tamanawas.[9] Potlatches were a common event across most North American Native tribes including the Twana.[3][9][14] Twana potlatches could be held at any time of the year but were common in the winter. The extravagant gathering was hosted or sponsored by an individual man or group of men, who were the gift-donors. Guests were invited from nearby villages and tribes, who recipients of the hosts' gifts, as a display of wealth and power.[14] These items of wealth could include woven blankets, dentalia, clamshell-disk beads, robes, pelts, bone war clubs, canoes, and slaves.[9] Upon death, bodies were not buried but placed in canoes or grave boxes, followed by a ceremonial gathering that included a feast and the deceased's belongings being given away.[9]

Some upper-class individuals of the Twana were members of a secret society, named after the society sprit "growling of an animal." The society held exclusive events similar to the potlatch, with an individual sponsor, feasts, and gifting. All members of the society possessed the society spirit, acquired through initiation. Members of the society were usually wealthy or upper-class, and initiation took place in adolescence. Initiation included several stages: showing the society spirit (where members ceremonially danced with duck-shaped rattles), laying down initiates (the initiates were sent into an unconscious trance after the society spirit possessed them), playing of the society spirit (members perform more dances for one or more nights), reviving the entranced initiates (the initiates, still unconscious, have blood dripped onto them and yelling society members lift them in the air a number of times until they awaken and run into the forest), bathing [ritually] the initiate (initiates are bathed in a river by their parents, given ceremonial garments, fed, and taught the secret society spirit dance), and working or practicing the initiate (society members and new initiates practice the society spirit dance and novices become entranced, represented by vomiting blood).[14]

Modern-day

editToday, most of the Twana population live on the Skokomish Indian Reservation and the Chehalis Indian Reservation. [3][9] On the Skokomish Reservation, Twana members hold personal naming and salmon run festivals. There is a tribal K-4 school on the Reservation. The Twana language is spoken and taught through a language project, and similarly there is a basket project that several neighboring tribes take part in.[9]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Skokomish Tribe | NPAIHB". February 9, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ Drachman, Gaberell (2020). tuwaduq - The Twana Language E-Dictionary Project. Skokomish Indian Tribe.

- ^ a b c d e f Thompson, M. Terry; Egesdal, Steven M. (January 1, 2008). Salish Myths and Legends: One People's Stories. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1764-5.

- ^ Ricky, Donald (January 1, 1999). Indians of Oregon. Somerset Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-403-09866-8.

- ^ Committee, Olympic Peninsula Intertribal Cultural Advisory (June 1, 2003). Native Peoples of the Olympic Peninsula: Who We Are. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3552-6.

- ^ Elmendorf, William Welcome (1993). Twana Narratives: Native Historical Accounts of a Coast Salish Culture. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0475-2.

- ^ "Skokomish Indian Tribe – A website for the Skokomish Tribe and its people". Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ King, Jonathan C. H. (1999). First Peoples, First Contacts: Native Peoples of North America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62654-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Pritzker, Barry (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- ^ "Creation of Washington Territory, 1853". www.oregonencyclopedia.org. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Treaty of Point No Point, 1855 | GOIA". goia.wa.gov. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Elmendorf, William W. (1960). The Structure of Twana Culture. Washington State University.

- ^ Pulsifer, Ralph. The Twana and the Drum (PDF).

- ^ a b c Elmendorf, William W. (October 12, 1948). "The Cultural Setting of the Twana Secret Society". American Anthropologist. 50 (4): 625–633. doi:10.1525/aa.1948.50.4.02a00050. PMID 18128883.