Upper Slaughter is a village in the Cotswold district of Gloucestershire, England, 4 miles (6.4 km) south west of Stow-on-the-Wold. The village lies off the A429, which is known as the Fosse Way,[2] and is located one mile away from its twin village Lower Slaughter, as well as being near the villages Bourton-on-the-Water, Daylesford, Upper Swell and Lower Swell. As of 2021, the village had a population of 181 inhabitants, an increase of 4 from 2011.

| Upper Slaughter | |

|---|---|

Upper Slaughter | |

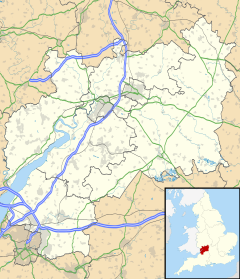

Location within Gloucestershire | |

| Population | 181 (2021)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SP154231 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CHELTENHAM |

| Postcode district | GL54 |

| Dialling code | 01451 |

| Police | Gloucestershire |

| Fire | Gloucestershire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

The village is built on both banks of the River Eye. The Anglican parish church is dedicated to Saint Peter.[3][4]

Upper Slaughter is one of a handful of the Thankful Villages,[5] amongst the small number in England which lost no men in World War I.[6] The village also lost no men in World War II, additionally making the village a Doubly Thankful Village.[6][7][8][9][10]

The parliamentary constituency is represented by Conservative Member of Parliament Geoffrey Clifton-Brown.

History

editThe name of the village derives from the Old English word "slohtre" meaning "wet land".[11][12]

In the past, some Roman burial mounds have found on the nearby Copse Hill.[13] Thus, it is very possible that Upper Slaughter was a settlement up to 2,000 years ago. More certainly, the manor of Upper Slaughter is recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086; the Slaughter family acquired it in the late 12th century.[14] The current building, on the site of an ancient building, was constructed over many years, starting in the Tudor era. Its crypt is estimated to be from the 14th century.[15] Moreover, Upper Slaughter was the site of a Norman adulterine castle, built by supporters of the Empress Matilda during The Anarchy of the 12th century. The remains of the castle are marked by the Castle Mound on the north edge of the village.

The largest business in the village is the Lords of the Manor Hotel. The building dates from 1649 since it separated from the Upper Slaughter Manor and has been a hotel since 1960s, furnished with portraits and antiques belonging to its former owner.[16] Other hotels serving the two Slaughter villages include The Slaughters Country Inn and Lower Slaughter Manor. In 1906, the cottages around the square were reconstructed by architect Sir Edward Lutyens.[17]

On the night of 4 February 1944 during Operation Steinbock a Luftwaffe bomber dropped 2000 incendiary bombs on Upper Slaughter. Despite some buildings sustaining damage there were no fatalities or injuries. Upper Slaughter is one of the Thankful Villages which lost no men in World War I. Furthermore, the village also lost no men in World War II, making it a Doubly Thankful Village. In the Cotswolds, the villages Little Sodbury and Coln Rogers are the only other villages to share this title.[18] Noting the contribution of local people to Britain’s war effort, the village hall displays a simple wooden plaque recording the 24 men and one woman in the First World War from Upper Slaughter, all of whom returned. In the Second World War, 36 joined up and 36 came home.[19]

Geography

editThe River Eye runs through Upper Slaughter,[20] culminating in the form of a ford.[21] The River Eye is a tributary of the River Windrush and it runs down all the way to neighbouring village Lower Slaughter and then eventually Bourton-on-the-Water. Arguably the main communal area of the village its situated near this brook, which is accompanied by a footbridge. Moreover, a large part of the village is situated at the bottom of Copse Hill.

Architecture

editPlaces of architectural interest include:

- St Peter's Church is a parish church which assuredly dates back to the 12th century, containing elements of Norman but also Saxon architecture and also memorials dedicated to the Slaughter Family.

- The Upper Slaughter Manor was mentioned in the Domesday Book in 1086 and was owned by nobleman Roger de Lacy for a period before being taken over by the Slaughter family. However, it was revarnished in the Elizabethan Age and also fell into disrepair in the 17th century. Finally, the Manor was restored in the 19th century and today is a private home open to tourists in select weeks.

- Eyford House is located at one end of Upper Slaughter and was voted the nation’s favourite house by County Life magazine in 2011. Although the house was built in the 19th century, it contains 17th century influences. Moreover, it is said that John Milton was inspired to write Paradise Lost on its grounds.[22]

- The Old School House is a former school which was built in the middle of the 19th century and still contains its school bell.

- The Square is adjacent to some medieval almshouses on the north side which are integrated with a few of 17th-century cottages – these were restored by Sir Edwin Lutyens in the early 20th century.[23] The Square also boasts a tiny Methodist chapel from 1865.[24]

- Home Farmhouse

- Castle Mound

- Rose Row

Notable residents

edit- Francis Edward Witts (1783–1854), a diarist, was an English clergyman who was rector of Upper Slaughter and wrote a book called The Diary of a Cotswold Parson.

- George Backhouse Witts (1846–1912), a civil engineer and archaeologist, was born in Winchcombe and lived in Upper Slaughter as a child owing to his father’s position as rector there. He was the grandson of diarist Francis Edward Witts.

- Guy Berryman (b. 1978), musician best known as the bassist for the rock band Coldplay.

In popular culture

editUpper Slaughter has served as a location for the television shows Father Brown, Our Mutual Friend and Interceptor, as well as the film The Sailor's Return.

Gallery

edit-

Upper Slaughter Manor from one side

-

Upper Slaughter Church

-

The River Eye

-

The Old School

-

Rose Cottages

-

Directions to other villages

See also

editReferences

editMedia related to Upper Slaughter at Wikimedia Commons

- ^ "Parish population 2015". Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "Things to do in Upper Slaughter, Cotswolds: A local's guide". Explore the Cotswolds. 15 November 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ The Buildings of England, ed Nikolaus_Pevsner

- ^ Elrington, C. R. (1965). A History of the County of Gloucester: volume 6. pp. 134–142.

- ^ "The thankful villages by Norman Thorpe, Rod Morris and Tom Morgan". Hellfirecorner.co.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ a b Kelly, Jon (11 November 2011). "Thankful villages: The places where everyone came back from the wars". BBC News. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "Parishes - Upper Slaughter | A History of the County of Gloucester: volume 6 (pp. 134–142)". British-history.ac.uk. 4 October 1913. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "The Slaughters". the Cotswolds.

- ^ "A guide to visiting Upper Slaughter in the Cotswolds". Pocket Wanderings. 3 July 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "10 Things To Do in Upper Slaughter, a Charming Cotswolds Village". Where Goes Rose. 4 February 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ The Cotswolds

- ^ "Things to do in Upper Slaughter, Cotswolds: A local's guide". Explore the Cotswolds. 15 November 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Upper Slaughter: History, tourist information, and nearby accommodation". Britain Express. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "A guide to visiting Upper Slaughter in the Cotswolds". Pocket Wanderings. 3 July 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Upper Slaughter Manor

- ^ "Lords of the Manor". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023.

- ^ "10 Things To Do in Upper Slaughter, a Charming Cotswolds Village". Where Goes Rose. 4 February 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "An Introduction to 'Thankful Villages'". heritage Calling. 11 November 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "An Introduction to 'Thankful Villages'". heritage Calling. 11 November 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "A guide to visiting Upper Slaughter in the Cotswolds". Pocket Wanderings. 3 July 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Things to do in Upper Slaughter, Cotswolds: A local's guide". Explore the Cotswolds. 15 November 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Things to do in Upper Slaughter, Cotswolds: A local's guide". Explore the Cotswolds. 15 November 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "10 Things To Do in Upper Slaughter, a Charming Cotswolds Village". Where Goes Rose. 4 February 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Things to do in Upper Slaughter, Cotswolds: A local's guide". Explore the Cotswolds. 15 November 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- The Buildings of England Gloucestershire 1: The Cotswolds, David Verey and Alan Brooks, Penguin Books 1999