Religion

editThe medieval St. Mary's Church, founded in the 14th century, was the centre of religious life in Swansea until the reformation and the subsequent proliferation of protestant denominations. By the mid-19th century nonconformist religious practice became the predominant form of worship, consolidated by an intensive period of chapel building and renovation.[1] A religious census of 1851 recorded 44 places of Nonconformist worship compared to 8 Anglican in the Swansea locality.[2]

The small Roman Catholic population in Swansea expanded rapidly in the 19th century with the influx of Irish immigrant workers. In 1888 what is now St Joseph Cathedral was constructed in the Greenhill district of Swansea.[3]

Bob Cuthill (2024) ‘Swansea Civic Centre: a History of the Site and Building’ The Swansea History Journal No. 32, pp. 20-34.

Colin Williams (2024) Why So Many Chapels? The Origins and Growth of Religious Nonconformity in Swansea Swansea: The Royal Institution of South Wales.

Price, R.T. (1992) Little Ireland: Aspects of the Irish and Greenhill, Swansea Swansea: Swansea City Council

Almanacer/sandbox | |

|---|---|

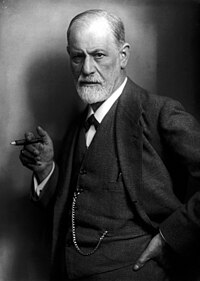

Sigmund Freud by Max Halberstadt, 1921 | |

| Born | Sigismund Schlomo Freud 6 May 1856 |

| Died | 23 September 1939 (aged 83) London, England |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna (MD, 1881) |

| Known for | Psychoanalysis |

| Spouse | Martha Bernays (m. 1886–1939, his death) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | University of Vienna |

| Academic advisors | |

| Signature | |

AWB Simpson In the Highest Degree Odious: Detention Without Trial in Wartime Britain, 1992 18Binterment regs

Martin and Walter Freud were both interned in 1940 as enemy aliens. Following a change in government policy on internment, both were subsequently recruited to the Pioneer Corps. After the war, denied recognition as a (Vienna-trained) lawyer by the British legal profession, Martin Freud ran a tobacconist shop in Bloomsbury.[31] His autobiographical memoir of Freud family life in Vienna, Glory Reflected, was published in 1952.[32] His sister, Mathilde Höllischer, opened 'Robell', a women's fashion store on Baker Street.[33]

Also interned Ernest Freud, Paula Fichte. Anna radio confiscated.

Freud's architect son, Ernst, arranged temporary accommodation for the Freuds in north London at 39 Elsworthy Road before the new family home was established in Hampstead at 20 Maresfield Gardens in September 1938. Ernst designed modifications of the building including the installation of an electric lift. The study and library areas were arranged to create the atmosphere and visual impression of Freud's Vienna consulting rooms.[5]

His sister, Mathilde Höllischer, opened 'Robell', a women's fashion emporium on Baker Street.[6]

Lusher, Adam (18 July 2008). "I am the forgotten Freud, says brother of Sir Clement Freud and Lucian Freud". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2009.[7]

Lucian gained exemption from conscription due to ill-health. He had enlisted for the Merchant Navy in 1941 and was discharged on his return from a trans-Atlantic crossing in a poor physical state.[8]

After the war Stephan worked in publishing, Lucian became well known as an artist, Clement as a broadcaster, journalist and MP.

Ernst resumed his architectural practice specialising in interior renovations. He worked on properties Anna Freud's Hampstead Clinic and Nursery expanded into on and nearby Maresfield Gardens, where he also rented a property.[9]

Ernst took over management of the copyright negotiations for the publication of his father's works and, in collaboration with Anna Freud, he made arrangements for the publication of their father's voluminous correspondence.[10] In accordance with Freud's wishes his grandchildren were to be the beneficiaries of royalties from his published works. Ernst Freud also began the adoption of the Suffolk seaside village of Walberswick as a favoured holiday destination for the Freuds, purchasing and renovating a property there in 1938.[11] A succession of Freuds purchased holiday homes there, including Anna and Clement Freud and his daughters Esther and Emma Freud.

STEPHAN ---- STEPHEN

Spender on Lucian (Feaver p 102) "As far as Lucian is concerned his grandfather lived in vain".

- Feaver, William (2018). The Lives of Lucian Freud, Vol.1. London: Bloomsbury.

Feaver, William (2018) The Lives of Lucian Freud, Vol.1 London: Bloomsbury.

- Freud, Clement (2001). Freud Ego. London: BBC.

|isbn=056353516

- Welter, Volker (2012). Ernst L. Freud, Architect. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0-85745-233-7.

‘Ernst L. Freud, Domestic Architect’ Yearbook of the Research Centre for German and Austrian Exile Studies Vol 6, 2005

Add Martin Glory Reflected

ALSO ADD WELTER TO FREUD ARTICLE in which the atmosphere and visual impression of Freud's Vienna consulting rooms were recreated.[12]

Ernst Freud and his three sons, Stephan, Clement and Lucian,were spared the ordeal of internment but only through through the intervention of his father’s close friend and colleague Princess Marie Bonaparte. His numerous attempts to secure naturalisation status for the family since their arrival in the UK in 1933 had met without success and, with preparations for war in place, by 1939 the government had banned all German citizens from the process. Bonaparte was in London to visit his ailing father who advised her of the problem. She took advantage of her royal family connections to persuade her relative, Prince George, Duke of Kent, to intervene with the immigration authorities and this secured the prompt issue of naturalisation documentation.[13] Ernst's three sons served during the war, Stephan and Clement in the army, Lucian in the Merchant Navy. After the war Stephan worked in publishing, Lucian became well known as an artist, Clement as a broadcaster, journalist and MP.

In the formative period .... in developing his theories ....

For Freud the Dora case study was illustrative of hysteria as a symptom and contributed to his understanding of the importance of transference as a clinical phenomena. In other of his early case studies Freud set out to describe the symptomology of obsessional neurosis, in the case of the Rat man, and phobia in the case of Little Hans.[14]

Ellen Cicely Wilkinson (ed) Why War?: Open Letters Between Einstein and Freud. London: New Commonwealth, 1934.

On this basis, Freud elaborated his theory of the unconscious ... his most distinctive discovery and object of enquiry

Freud's legacy, though a highly contested area of controversy, has been assessed as "one of the strongest influences on twentieth-century thought, its impact comparable only to that of Darwinism and Marxism,"[15] with its range of influence permeating "all the fields of culture ... so far as to change our way of life and concept of man."[16]

S arrived in London in mysterious circumstances where he met Freud's brother Alexander.

[17]

- I agree with FKC that the range of sources and complexity of the debates indicates that your proposed content is not appropriate for the lead given the need to keep the lead a concise summary with reference to the main areas of controversy. Specifics of the debates can then be detailed in the body of the article which allow for a NPOV presentation. That said, it would be preferably not to have Freud-war rhetoric in the article about pseudoscience or statements about what supplanted Freudianism stated as incontrovertible fact. Also the general claim that "The intellectual influence of psychoanalysis peaked in the middle of the 20th century" is challengeable for a range of reliable sources which would need to be represented according to NPOV guidelines. It is of course generally agreed that psa in in general decline clinically which the phrase "psa remain influential" does not adequately convey. I've added to the sentence accordingly. Almanacer (talk) 13:14, 9 December 2016 (UTC)

I've removed the cut and paste from In the Life and Death Instincts section. As explained here I don't see a rewrite as necessary as the content was off-topic in the first place. No reason it can't be included elsewhere in the article. Almanacer (talk) 11:51, 22 December 2016 (UTC)

Laplanche, Jean; Pontalis, Jean-Bertrand (1988). The Language of Psycho-analysis. London: Karnac Books. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-946439-49-2.</ref>

Eric Mosbacher with James Strachey (Eds) The origins of psycho-analysis. Letters to Wilhelm Fliess, drafts and notes: 1887–1902 by Sigmund Freud. Translated from the German Aus den Anfängen der Psychoanalyse. Briefe an Wilhelm Fliess. London: Imago Publishing Co., 1954

Eric Mosbacher with James Strachey (Eds) The Origins of Psycho-analysis. Letters to Wilhelm Fliess, drafts and notes: 1887–1902 by Sigmund Freud. London: Imago Publishing Co., 1954

Laplanche, Jean; Pontalis, Jean-Bertrand (1988). The Language of Psycho-analysis. London: Karnac Books. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-946439-49-2.</ref>

I agree with User:Avaya1 re. removing: "undue - editorializing, images of other writers on a figure's biography. Little precedent for this on Wikipedia." I can't find any similar article with such images. There's no Hayek in the Marx article !? Formatting issues should not weigh significantly in determining content. Almanacer (talk) 10:13, 16 May 2018 (UTC)

RELOCATE TO EARLY PSA MVMT

The 1922 Berlin Congress was the last Freud attended. By this time his speech had become seriously impaired by the prosthetic device he needed as a result of a series of operations on his cancerous jaw. He kept abreast of developments through a regular correspondence with his principal followers and via the circular letters and meetings of the secret Committee which he continued to attend.

The Committee continued to function until 1927 by which time institutional developments within the IPA, such as the establishment of the International Training Commission, had addressed concerns about the transmission of psychoanalytic theory and practice. There remained, however, significant differences over the issue of lay analysis - i.e. the acceptance of non-medically qualified candidates for psychoanalytic training. Freud set out his case in favour in 1926 in his The Question of Lay Analysis. He was resolutely opposed by the American societies who expressed concerns over professional standards and the risk of litigation (though child analysts were made exempt). These concerns were also shared by some of his European colleagues. Eventually an agreement was reached allowing societies autonomy in setting criteria for candidature.[18]

Bibliog Further Reading

editBiographies

edit- Breger, Louis (2001). Freud: Darkness in the Midst of Vision. New York: Wiley.

- Clark, Ronald W. (1980). Freud: the Man and His Cause. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Ferris, Paul (1997). Dr Freud: A Life. London: Sinclair-Stevenson.

- Flem, Lydia (2002). Freud the Man: An Intellectual Biography. New York: Other Press.

- ffytche, Matt (2022). Sigmund Freud. Critical Lives. London: Reaktion Books.

- Gay, Peter (2006) [1988]. Freud: A Life for Our Time (2nd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton.

- Jones, Ernest (1953). Sigmund Freud: Life and Work: Vol 1: The Young Freud 1856–1900. London: Hogarth Press.

- Jones, Ernest (1955). Sigmund Freud: Life and Work: Vol 2: The Years of Maturity 1901–1919. London: Hogarth Press.

- Jones, Ernest (1957). Sigmund Freud: Life and Work: Vol 3: The Final Years 1919–1939. London: Hogarth Press.

- Jones, Ernest (1961). Trilling, Lionel; Marcus, Stephen (eds.). Sigmund Freud: Life and Work (Abridged ed.). New York: Basic Books.

- Phillips, Adam (2014). Becoming Freud. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Puner, Helen Walker (1947). Freud: His Life and Mind. New York: Howell Soskin.

- Roudinesco, Elizabeth (2016). Freud: In His Time and Ours. Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Press.

- Schur, Max (1972). Freud: Living and Dying. London: Hogarth Press.

- Ruth, Sheppard (2012). Explorer of the Mind: The Illustrated Biography of Sigmund Freud. London: Andre Deutsch.

- Whitebook, Joel (2017). Freud: An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Further Reading

edit- Brown, Norman O. Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytic Meaning of History. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, Second Edition 1985.

- Cioffi, Frank. Freud and the Question of Pseudoscience. Peru, IL: Open Court, 1999.

- Cole, J. Preston. The Problematic Self in Kierkegaard and Freud. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1971.

- Crews, Frederick. The Memory Wars: Freud's Legacy in Dispute. New York: The New York Review of Books, 1995.

- Crews, Frederick. Unauthorized Freud: Doubters Confront a Legend. New York: Penguin Books, 1998.

- Crews, Frederick. Freud: The Making of an Illusion. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2017. ISBN 978-0742522633

- Dufresne, Todd. Killing Freud: Twentieth-Century Culture and the Death of Psychoanalysis. New York: Continuum, 2003.

- Dufresne, Todd, ed. Against Freud: Critics Talk Back. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

- Ellenberger, Henri. Beyond the Unconscious: Essays of Henri F. Ellenberger in the History of Psychiatry. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Ellenberger, Henri. The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. New York: Basic Books, 1970.

- Esterson, Allen. Seductive Mirage: An Exploration of the Work of Sigmund Freud. Chicago: Open Court, 1993.

- Gay, Peter. Freud: A Life for Our Time. London: Papermac, 1988; 2nd revised hardcover edition, Little Books (1 May 2006), 864 pages, ISBN 978-1-904435-53-2; Reprint hardcover edition, W.W. Norton & Company (1988); trade paperback, W.W. Norton & Company (17 May 2006), 864 pages, ISBN 978-0-393-32861-5

- Gellner, Ernest. The Psychoanalytic Movement: The Cunning of Unreason. London: Fontana Press, 1993.

- Grünbaum, Adolf. The Foundations of Psychoanalysis: A Philosophical Critique. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

- Grünbaum, Adolf. Validation in the Clinical Theory of Psychoanalysis: A Study in the Philosophy of Psychoanalysis. Madison, Connecticut: International Universities Press, 1993.

- Hale, Nathan G., Jr. Freud and the Americans: The Beginnings of Psychoanalysis in the United States, 1876–1917. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Hale, Nathan G., Jr. The Rise and Crisis of Psychoanalysis in the United States: Freud and the Americans, 1917–1985. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Hirschmüller, Albrecht. The Life and Work of Josef Breuer. New York University Press, 1989.

- Jones, Ernest. The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud. 3 vols. New York: Basic Books, 1953–1957

- Jung, Carl Gustav. The Collected Works of C. G. Jung Volume 4: Freud and Psychoanalysis. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1961.

- Macmillan, Malcolm. Freud Evaluated: The Completed Arc. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1997.

- Marcuse, Herbert. Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud. Boston: Beacon Press, 1974

- Masson, Jeffrey Moussaieff. The Assault on Truth: Freud's Suppression of the Seduction Theory. New York: Pocket Books, 1998

- Puner, Helen Walker. Freud: His Life and His Mind. New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1947

- Ricœur, Paul. Freud and Philosophy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970.

- Rieff, Philip. Freud: The Mind of the Moralist. Garden City, New York: Anchor Books, 1961

- Roazen, Paul. Freud and His Followers. New York: Knopf, 1975, hardcover; trade paperback, Da Capo Press (22 March 1992) ISBN 978-0-306-80472-4

- Roazen, Paul. Freud: Political and Social Thought. London: Hogarth Press, 1969.

- Roth, Michael, ed. Freud: Conflict and Culture. New York: Vintage, 1998.

- Schur, Max. Freud: Living and Dying. New York: International Universities Press, 1972.

- Stannard, David E. Shrinking History: On Freud and the Failure of Psychohistory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Webster, Richard. Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science and Psychoanalysis. Oxford: The Orwell Press, 2005.

- Wollheim, Richard. Freud. Fontana, 1971.

- Wollheim, Richard, and James Hopkins, eds. Philosophical essays on Freud. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Seduction Theory

editIn abandoning Seduction Theory - the notion that sexual abuse was a precondition of psychoneurosis, and that every account he heard of it from his patients was a true account of actual events.... expanded view of sexuality. But at no stage did Freud ever abandon the belief that children were abused and that such abuse caused lasting psychological harm.[19] However, discrepancies in the various accounts Schur gave of his role in Freud’s final hours, which have in turn led to inconsistencies between Freud’s main biographers (notably Gay and Jones), has led to further research and a revised account. This proposes that Schur was absent from Freud’s deathbed when a third and final dose of morphine was administered by Dr Josephine Stross, a colleague of Anna Freud’s. This led to Fteud’s death around midnight on 23 September.[20]

Iceberg image

edit

Bernays

editMinna Bernays, Martha Freud's sister, became a permanent member of the Freud household in 1896, after the death of her fiancé. The close relationship she formed with Freud led to rumours, started by Carl Jung, of an affair. The discovery of a Swiss hotel log of 13 August 1898, signed by Freud whilst travelling with his sister-in-law, has been adduced as evidence of the affair.[22]

Professorship

editIn 1902 Freud at last realised his long-standing ambition to be made a university professor. The title “professor extraordinarius” [23] was important to Freud for the recognition and prestige it conferred, there being no salary or teaching duties attached to the post (he would be granted the enhanced status of “professor ordinarius” in 1920[24]). Despite support from the university his appointment had been blocked in successive years by the political authorities and it was only secured with the intervention of one of his more influential ex-patients, a Baroness Marie Ferstel, who had to bribe the minister of education with a painting.[25]

With his prestige thus enhanced Freud continued with the regular series of lectures on his theories which, since the mid-1880s as a docent of the University, he had been delivering to small audiences every Saturday evening at the lecture hall of the University's psychiatric clinic.[26]

Solms

editin the emerging field of neuro-psychoanalysis, founded by neuroscientist and psychoanalyst Mark Solms,[27] has proved controversial with some psychoanalysts criticising the very concept.[28] Solms has argued for neuro-scientific findings being "broadly consistent" with Freudian theories pointing out brain structures relating to Freudian concepts such as libido, drives, the unconscious, and repression.. [29][30] Neuroscientists who have endorsed Freud’s work include David Eagleman who believes that Freud "transformed psychiatry" by providing "the first exploration of the way in which hidden states of the brain participate in driving thought and behavior"[31] and Nobel laureate Eric Kandel who argues that "psychoanalysis still represents the most coherent and intellectually satisfying view of the mind."[32]

There is a substantial body of research which demonstrates the efficacy of the clinical methods of psychoanalysis[33] and of related psychodynamic therapies in treating a wide range of psychological disorders.[34]

Solms, Mark (2018). "The scientific standing of psychoanalysis". BJPsych International. 15 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1192/bji.2017.4. PMC 6020924. PMID 29953128.

Predictions of a progressive decline in support for psychodynamic therapies[35] have been contradicted by research evidence in support of its efficacy in treating a wide range of psychological disorders.[36]

Feminism psa debate

editFreud article Femininity

editFreud’s account of femininity is grounded in his theory of psychic development as it traces the uneven transition from the earliest stages of infantile and childhood sexuality characterised by “polymorphous perversity” and a bisexual disposition through to the fantasy scenarios and rivalrous identifications of the Oedipus complex on to the greater or lesser extent these are modified in adult sexuality. There are different trajectories for the boy and the girl which arise as effects of the castration complex. Anatomical difference, the possession of a penis, induces castration anxiety for the boy whereas the girl experiences a sense of deprivation. In the boy’s case the castration complex concludes the Oedipal phase whereas for the girl it precipitates it.[37]

The constraint of the erotic feelings and fantasies of the girl and her turn away from the mother to the father is an uneven and precarious process entailing “waves of repression”. The normal outcome is, according to Freud, the vagina becoming “the new leading zone” of sexual sensitivity displacing the previously dominant clitoris the phallic properties of which made it indistinguishable in the child’s early sexual life from the penis. This leaves a legacy of penis envy and emotional ambivalence for the girl which was “intimately related the essence of femininity” and leads to “the greater proneness of women to neurosis and especially hysteria.”[38] In his last paper on the topic Freud likewise concludes that “the development of femininity remains exposed to disturbance by the residual phenomena of the early masculine period... Some portion of what we men call the ‘enigma of women’ may perhaps be derived from this expression of bisexuality in women’s lives.”[39]

Initiating what became the first debate within psychoanalysis on femininity, Karen Horney of the Berlin Institute set out to challenge Freud's account of femininity. Rejecting Freud's theories of the feminine castration complex and penis envy, Horney argued for a primary femininity and penis envy as a defensive formation rather than arising from the fact, or "injury", of biological asymmetry as Freud held. Horney had the influential support of Melanie Klein and Ernest Jones who coined the term "phallocentrism" in his critique of Freud's position.[40]

In defending Freud against this critique, feminist scholar Jacqueline Rose has argued that it presupposes a more normative account of female sexual development than that given by Freud. She finds that Freud moved from a description of the little girl stuck with her 'inferiority' or 'injury' in the face of the anatomy of the little boy to an account in his later work which explicitly describes the process of becoming 'feminine' as an 'injury' or 'catastrophe' for the complexity of her earlier psychic and sexual life.[41]

Throughout his deliberations on, as he put it, the “dark continent” of female sexuality and the "riddle" of femininity, Freud was careful to emphasise the “average validity” and provisional nature of his findings. He did, however, in response to his critics, maintain a steadfast objection "to all of you ... to the extent that you do not distinguish more clearly between what is psychic and what is biological..."[42]

Moi, Toril (March 2004). "From Femininity to Finitude: Freud, Lacan, and Feminism, again". Signs Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 03/2004; 29(3): 871. doi:10.1086/380630.

Secret Committee

editSecret Committee of the early history of psychoanalysis was formed in 1912 in order to oversee the development of psychoanalysis and protect the theoretical and institutional legacy of Freud’s work. [43]

The Committee was formed at the suggestion of Ernest Jones in response to Freud’s concerns over the consequences of disputes over theoretical issues in psychoanalysis. These had already resulted in the acrimonious departure of Adler and Stekel from Freud’s inner circle of followers and by 1912 Freud’s relationship with Jung was reaching the point of terminal breakdown. In this context Freud wrote to Jones endorsing “your idea of a secret council composed of the best and most trustworthy among our men to take care of the further development of psychoanalysis and defend the cause against personalities and accidents when I am no more”.[44]

The Committee membership comprised Ernest Jones who served as the chairman, Sándor Ferenczi, Otto Rank, Hans Sachs, and Karl Abraham. Max Eitingon joined the Committee in 1919. Anna Freud replaced Rank in 1924.

The Committee first met on 25 May 1913 when Freud presented each member with a Greek intaglio mounted on a golden ring. They all undertook not to publish work which could be seen as departing from any of the fundamental tenets of psychoanalytical theory without prior discussion in the Committee.[45] As well a regular meetings, the Committee established a practice of sending circular letters as a means of communication.

Jones intended the immediate political objective of forming the Committee to be the isolation Jung and ultimately to force his resignation as president of the International Psychoanalytic Association. Though this transpired in 1914, his ambition to succeed Jung, endorsed by the Committee, was frustrated by the outbreak of war. [46]

Later developments

editThe Committee functioned well for a full decade, despite a world war, but dissension involving Rank and Ferenczi led to its dissolution in 1924.[47] It was reconstituted later the same year, with Anna Freud replacing Rank, and resumed the practice of sending circular letters.[48] After the death of Abraham in 1925 and Ferenczi in 1933 it ceased to function.

Bibliography

edit- Gay, Peter (2006) [1988]. Freud: A Life for Our Time (2nd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton.

- Jones, Ernest (1955). Sigmund Freud: Life and Work: Vol 2: The Years of Maturity 1901–1919. London: Hogarth Press.

- Maddox, Brenda (2006). Freud's Wizard: The Enigma of Ernest Jones. London: John Murray.

work_institutions = Royal Free Hospital

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital Oxford University Medical School Oxford Institute of Social Medicine Department of Public health and Epidemiology, University of Birmingham

Early life

editStewart was born in Sheffield, England, the daughter of two physicians, Lucy (née Wellburn) and Albert Naish. Both were pioneers in paediatrics, and both became heroes in Sheffield for their dedication to children's welfare. Alice studied pre-clinical medicine at Girton College, Cambridge, and in 1932 completed her clinical studies at the Royal Free Hospital, London. She gained experienced in hospital posts in Manchester and London, and in 1936 passed the examinations for membership of the Royal College of Physicians. From 1935 she held the post of registrar at the Royal Free Hospital and from 1939 a consultant post at the Elizabeth Garratt Anderson hospital. In 1941 she moved to Oxford to take up a temporary residency at the Radcliffe Infirmary after which she was recruited by Radcliffe professor Dr. Leslie Witts to a post as his senior assistant working at the Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine and it was there she developed her interest in social medicine, researching health problems experienced by wartime munitions workers.[49] Royal Free Hospital Department of Public health and Epidemiology, University of Birmingham Oxford Institute of Social Medicine Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital

Epidemiological studies

editThe department of social and preventive medicine at Oxford was created in 1942, with Stewart as assistant head. In 1950 she succeeded as head of the unit, but to her disappointment she was not granted the title of "professor", as awarded to her predecessor, because by then the post was considered not to be of great importance.[51] Nonetheless, in 1953 the Medical Research Council allocated funds to her pioneering study of x-rays as a cause of childhood cancer, which she worked on from 1953 until 1956. Her results were initially regarded as unsound. Her findings on fetal damage caused by x-rays of pregnant women were eventually accepted worldwide and the use of medical x-rays during pregnancy and early childhood was curtailed as a result (although it took around two and a half decades).[52] Stewart retired in 1974.

Her most famous investigation came after her formal retirement, while an honorary member of the department of social medicine at the University of Birmingham.[51] Working with Professor Thomas Mancuso of the University of Pittsburgh she examined the sickness records of employees in the Hanford plutonium production plant, Washington state, and found a far higher incidence of radiation-induced ill health than was noted in official studies.[53]

Sir Richard Doll, the epidemiologist respected for his work on smoking-related illnesses, attributed her anomalous findings to a "questionable" statistical analysis supplied by her assistant, George Kneale (who was aware of, but may have miscalculated, the unintentional "over-reporting" of cancer diagnoses in communities near to the works). Stewart herself acknowledged that her results were outside the range considered statistically significant.[54][55]

Today, however, her account is valued as a response to the perceived bias in reports produced by the nuclear industry.[51][56]

In 1986, she was added to the roll of honour of the Right Livelihood Foundation, an annual award presented in Stockholm.[57] Stewart eventually gained her coveted title of "professor" through her appointment as a professorial fellow of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.[58] In 1997 Stewart was invited to become the first Chair of the European Committee on Radiation Risk.[59]

Description

editThe area consists mainly of suburban housing located on the steep south-eastern slopes of Townhill. The demographic of the area was changed in recent years with the expansion of the former Swansea Metropolitan University campus on the main Mount Pleasant road and the arrival of a substantial student population.

Constitution Hill

editConstitution Hill, one of the steepest road hills in Swansea, leads up towards Mount Pleasant from the city centre. It is a steep, sloping cobbled street which featured in the film Twin Town in a scene with a daring car stunt. In the early 20th century, the Swansea Constitution Hill Incline Railway operated up and down the hill. Constitution Hill forms part of the boundary between the Castle and Uplands wards.

Thoroughfare

editMansell Street, De La Beche Street, Grove Place, and Alexandra Road cross the southern fringes of the area as a continuous thoroughfare. Located on this thoroughfare are Swansea Magistrates' Court,[60] Swansea Central police station, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, the old Swansea Central Library and the building housing the arts wing of the university. Alexandra Road is a designated conservation area, and consists of a number of buildings which were constructed between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The road has a number of shops, including a new Tesco Express, opened in 2008.

History

editA workhouse opened in Mount Pleasant in 1862, between what was known as "Gibbet Hill" (now North Hill Road) and a lower slope known as "Poppit Hill". In 1895, it held 584 inmates in extended buildings. It was later called Tawe Lodge, and eventually became Mount Pleasant Hospital in 1929, when it was taken over by Swansea County Borough Council. The hospital closed in 1995 and was converted into social housing.[61] Hospital records are now held by the West Glamorgan Archive Service,[62] as are records of the original Swansea Poor Law Union from 1842 to 1960.[63]

In 1853 the Swansea Grammar School for Boys, moved from the city centre to a new building on Mount Pleasant designed by the architect Thomas Taylor. The building was extended in 1869 to a design by Benjamin Bucknall. From 1895 the site was shared with the newly created Swansea Intermediate and Technical School for Boys (later the co-educational Swansea Technical College). After much of the site was destroyed by incendiary bombs during World War II the Grammar School relocated to the Sketty area as Bishop Gore Grammar School in 1952. The Technical College remained on a redeveloped site and in 1976 was incorporated into the West Glamorgan Institute of Higher Education, redesignated in 2008 as Swansea Metropolitan University, which in 2013 became a constituent member of the University of Wales Trinity Saint David. The University closed its Mount Pleasant campus in 2018 relocating most of its faculties to the SA1 Waterfront area.[64] The Arts faculty, Swansea College of Arts, remains in Mount Pleasant on its Alexander Road site where a new building was opened in 2015 in a redevelopment of the former Dynevor Grammar School site.

Terrace Road which runs off Mount Pleasant to the west has two notable buildings: a Primary School which opened in 1888 and has approximately 300 pupils[65] and St Jude's Church which dates from 1904.

The second night of bombing saw the most concentrated loss of civilian life in the blitz on Swansea. At Teilo Crescent, in the Mayhill district of the town, 14 homes were destroyed and 24 residents as well as 6 firemen and civil defence volunteers perished. [66] Altogether 38 people in the locality were killed during the raid. There was also extensive damage to the Mount Pleasant,Cwmbwrla and Manselton residential districts.[67]

and 230 people were dead and 409 injured. Moreover, 7,000 people had lost their homes.

https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/swansea-townhill-pobl-morganstone-university-23600009

- Jenkins, Nigel (2008). Real Swansea. Bridgend: Seren.

- Robins, Nigel (1992). Homes for Heroes: Early Twentieth-Century Council Housing in the County Borough of Swansea. Swansea: Swansea City Council.

In medieval Swansea the Townhill area was a combination of woodland and heathland designated as common land. It was commonly referred to as “the mountain” and in Welsh as Graig Llwyd. The name Town Hill came into common use in the mid-18th century. After the 1762 Enclosure Act the area was, apart from remnants of the (still surviving) heathland, transformed into farmland.[68]

In 1912 the Swansea Training College for teachera moved from the city centre to a new building on the Western slopes of Townhill. It subsequently became part of the West Glamorgan Institute of Higher Education (from 1976 to 1992) and then the Swansea Institute (from 1992 to 2008) Thereafter it became a campus of Swansea Metropolitan University which later merged with the University of Wales Trinity Saint David. The campus was closed in 2018 and the site allocated for a council housing development in which the features of the original 19th century building were to be preserved.[69]

The university merged with, and became a constituent campus of, , and the Townhill campus later closed.

During a German bombing raid on February 20, 1941, twenty-four residents and another six firemen and civil defence volunteers perished at Teilo Crescent, Mayhill. A memorial plaque in Teilo Crescent commemorates the lost lives and those of others from Mayhill and the neighbouring Townhill district killed in the Second World War.[70]

MAYHILL WASHING LAKE

edit'Golchi' Mayhill & Hillside Community Food Garden

History of the Ravine, from the old 'Washing' Lake down to the new Food Garden Hanes y Ceunant, o'r hen 'Lyn' Golchi hyd at yr Ardd Fwyd newydd

A good reliable water supply has always been essential for any town, and any stream or spring that is used quickly becomes a central part of local life. This pond and the stream running through it, which arises from a spring on the hill, is the most famous. It was known for hundreds of years as "Washing' Lake which is derived from the Old English words 'waesse' and lacu' meaning wet or swampy stream.

In medieval times it would be a place to do the washing. The stream has never been known to dry up, providing much of the western side of medieval Swanses with their water supply. The lower reaches of the stream were equally useful as a sewer emptying into the town ditch. By the 1700s the stream was used to feed the large tannery that was built on the western side of town-today's Kingsway.

The stream figured in early attempts to build reservoirs in the 1800, to try and improve the town's water supply originally serving the Work House, and running down the side of the road known as Bryn Syl. tathas traces of the cast iron pipes and sanmtione walls from that time The Washing Lake survived redevelopment throughout the 20th century, and is still part the Hillside Wilde Corridor, linking Bryn y Don Park with Rosehill Quarry

The wildlife corridor stretching around Townhill and Mayhill came about from the Enclosure Act of 1762 when the whole of the hill became a quilted patchwork of fields surrounded by hedges. In the 1760s Cae Cwm held was one of those that made up Gabriel Powers Farm. The track that runs from North Hill, originally Gibbet Hill to May Hill, was the farm track known as the Black Road, Above the lane is 'Cae Round Top

And present day... Hyd heddiw...

At the top of the cavine our friends of group help to look after the pond, repairing & weeding the paths, and generally seeing the area tidy. It's now a nasant spot where you can look for newts, watch bints in the day, maybe busts or foxes in the evening see yellow Tags' around the pond, damselfies & butterflies drifting www bluebells ant the slope, and f you are really lucky apot the odd Radkeverhead

COMMUNITY FOOD GARDEN

And if you wander down the bottom of the path you will find our unique food garden for the local community to grow their own frutt & veg. We have made raised beds using old railway sleepers, planks of wood, and thanted tys, aha i campost heaps, started an orchart, with cherry & apple trees, goberry & rebus young hawthom heodge, all finished off with a decorative Wishing Well Look out for the daffodils in Spring

History text provided by Nigel Robbins & Roy Kneath; Information Board donated by Townhill Ward Cllrs David Hopkins, Cyril Anderson & Lesley Walton

In the middle ages Townhill was largely an area of heathland designated as common land. The name Town Hill came into common use in the 18th century before which it was commonly referred to as “the mountain” and in Welsh as Graig Llwyd. After the 1762 Enclosure Act the area was, apart from remnants of the heathland (which remain to this day), transformed into farmland.[71]

sandboxes

editUser:Almanacer/sandbox4 Swansea History

citations

editBlitz is a 2024 film produced and directed by Steve McQueen. In a graphic representation of the Blitz on London, set over a period of three nights in September 1940, the themes of patriotism, communal solidarity and resilience and moments of mental terror across gender, race and class are all explored in a manner which questions the “patriotic myth” of the prevailing historical imagination. Gary Younge on Blitz [73]

Wales had been hard hit by deindustrialisation and high unemployment in the 1920s and 1930s. The war turned the economy around.[74] When, in the first months of the war, Wales was too distant for German bombers and as it had a large pool of unemployed men immediately available for work, it suddenly became an attractive relocation destination for war industries and ordinance factories. The historic basic industries of coal and steel saw a very heavy new demand. The best coal seams had long been depleted. It was more and more expensive to get to the remaining coal, but coal was urgently needed, and shipping it in from North America would overburden the limited supply system.[75] After the German occupation of France put Wales within the range of the Luftwaffe, its ports and industrial centres became subject to episodes of intensive bombardment.[76]

Lacan

editRoudinesco, E. (1999) Jacques Lacan: An Outline of a Life and a History of a System of Thought. Trans. Barbara Bray. Cambridge. Columbia University Press.

Elisabeth Roudinesco, Jacques Lacan & Co.: a history of psychoanalysis in France, 1925–1985, 1990, Chicago University Press,

- Roudinesco, Elizabeth (2016). Freud: In His Time and Ours. Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Press.[77]

Macey, David (1988). Lacan in Contexts. London: Verso. ISBN 0860919420.

Barzilai, Shuli (1999). Lacan and the matter of origins Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

Zapancic, A (2000). Ethics of the Real: Kant, Lacan. London: Verso.

Ruti, M. (2012) The Singularity of Being: Lacan and the Immortal Within. New York: Fordham University Press.

Ruti, M. (2015) Between Levinas and Lacan: Self, Other, Ethics. London: Bloomsbury

Shepherdson, C. (2008) Lacan and the Limits of Language. New York: Fordham University Press.

Freud

editLaplanche, Jean; Pontalis, Jean-Bertrand (1988). The Language of Psycho-analysis. London: Karnac Books. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-946439-49-2.

Gay, Peter (2006) [1988]. Freud: A Life for Our Time (2nd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton.

Ffytche, Matt (2022). Sigmund Freud. Critical lives. London: Reaktion books. ISBN 978-1-78914-579-3.

Jones

editMaddox, Brenda (2006). Freud's Wizard: The Enigma of Ernest Jones. London: John Murray.

Jones, Ernest (1955). Sigmund Freud: Life and Work: Vol 2: The Years of Maturity 1901–1919. London: Hogarth Press.

\* Brome, Vincent (1982). Ernest Jones: Freud's Alter Ego. London: Caliban Books.

- Davies, T. G. (1979). Ernest Jones: 1879–1958. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- ——— (2001). "Jones, Alfred Ernest". In Roberts, Brynley F. (ed.). The Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Aberystwyth, Wales: National Library of Wales. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- Jones, Ernest (1927). "The Early Development of Female Sexuality". International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 8: 459–472. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ——— (1933). "The Phallic Phase". International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 14: 1–33.

- ——— (1935). "Early Female Sexuality". International Journal of Psycho-Analysis. 16: 263–273.

- ——— (1952) [1931]. The Elements of Figure Skating (rev. ed.). London: Allen and Unwin.

- ——— (1959). Free Associations: Memories of a Psycho-Analyst. London: Hogarth Press.

- Maddox, Brenda (2006). Freud's Wizard: The Enigma of Ernest Jones. London: John Murray.

- Mitchell, Juliet (2000) [1974]. Psychoanalysis and Feminism. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin.

- Paskauskas, R. Andrew (1988). "Freud's Break with Jung: The Crucial Role of Ernest Jones". Free Associations (11): 7–34. ISSN 2047-0622.

- ——— , ed. (1993). The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones, 1908–1939. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-15423-0.

Klein

editInfluence on feminism

In Dorothy Dinnerstein’s book The Mermaid and the Minotaur (1976) (also published in the UK as The Rocking of the Cradle and the Ruling of the World), drawing from elements of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis, particularly as developed by Klein, Dinnerstein argued that sexism and aggression are both inevitable consequences of child rearing being left exclusively to women.[9] As a solution, Dinnerstein proposed that men and women equally share infant and child care responsibilities.[10] This book became a classic of U.S. second-wave feminism and was later translated into seven languages.[11]

EJ

editMLO

editIn 1917 Jones married the Welsh musician Morfydd Llwyn Owen. They were holidaying in South Wales the following year when Morfydd became ill with acute appendicitis. Jones hoped to get his former colleage and brother-in-law, the leading surgeon Wilfred Trotter, to Swansea in time to operate but when this proved impossible emergency surgery was carried out at his parents Swansea home by a local surgeon, with chloroform administered as the anaesthetic.[78][79] As Jones recounts: "after a few days [she] became delirious with a high temperature. We thought there was blood poisoning till I got Trotter from London. He at once recognized delayed chloroform poisoning ... We fought hard, and there were moments when we seemed to have succeeded, but it was too late.”[80] Jones had his wife buried buried in Oystermouth Cemetery on the outskirts of Swansea with her gravestone bearing an inscription from Goethe's Faust, "Das Unbeschreibliche, hier ist's getan".[b][11]

Lacan

editJacques Marie Émile Lacan (/ləˈkɑːn/;[81] French: [ʒak lakɑ̃]; 13 April 1901 – 9 September 1981) was a French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist who has been called "the most controversial psycho-analyst since Freud".[82]

Giving yearly seminars in Paris from 1953 to 1981, Lacan’s work has marked the French and international intellectual landscape, having made a significant impact on continental philosophy and cultural theory in areas such as post-structuralism, critical theory, and film theory as well as on psychoanalysis itself.

Lacan took up and discussed the whole range of Freudian concepts emphasising the philosophical dimension of Freud’s theories and applying concepts derived from structuralism in linguistics and anthropology to their development. Taking this direction and introducing controversial innovations in clinical practice led to Lacan establishing new psychoanalytic institutions to promote and develop his work which he saw as a “return to Freud” in opposition to prevailing trends in psychoanalysis collusive of adaptation to social norms.

The Seminars

editI 1953-4 Freud's papers on technique.

II 1954-5 The ego in Freud's theory and in the technique of psychoanalysis.

III 1955-6 The psychoses.

IV 1956-7 Object relations

V 1957-8 The formations of the unconscious.

VI 1958-9 Desire and its interpretation.

VII 1959-60 The ethics of psychoanalysis.

VIII 1960-1 Transference.

IX 1961-2 Identification.

X 1962-3 Anxiety.

XI 1964 The four fundamental concepts of psychoanalysis.

XII 1964-5 Crucial problems for psychoanalysis.

XIII 1965-6 The object of psychoanalysis.

XIV 1966-7 The logic of fantasy.

XV 1967-8 The psychoanalytic act.

XVI 1968-9 From one other to the Other.

XVII 1969-70 The reverse of psychoanalysis.

XVIII 1970-1 On a discourse that would not be semblance.

XIX 1971-2 ...Or worse.

XX 1972-3 Encore.

XXI 1973-4 The non-duped err/The names of the father.

XXII 1974-5 RSI.

XXIII 1975-6 The sinthome.

XXIV 1976-7 One knew that it was a mistaken moon on the wings of love.

XXV 1977-8 The moment of concluding.

XXVI 1978-9 Topology and time,

XXVII 1980 Dissolution.

Sexuality

editGiven the context of her intimate relationships with Lou Andreas-Salome and Dorothy Burlingham, and notwithstanding her life-long denial of any sexual relationships,[83] claims have been made that it was repression of her homoerotic sexuality that influenced her in the pathologizing of homosexuality in her clinical work as well as in her prominent advocacy of the policy of the International Psychoanalytical Association which debarred homosexuals as candidates for training as psychoanalysts.[84]

Marilyn Monroe In 1922 Anna Freud presented her paper "Beating Fantasies and Daydreams" to the Vienna Psychoanalytical Society and became a member of the society. In 1923, she began her own psychoanalytical practice with children and by 1925 she was teaching at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Training Institute on the technique of child analysis, her approach to which she set out in her first book, An Introduction to the Technique of Child Analysis, published in 1927.

Among the first children Anna Freud took into analysis were those of Dorothy Burlingham. In 1925 Burlingham, heiress to the Tiffany luxury jewellery retailer, had arrived in Vienna from New York with her four children and entered analysis firstly with Theodore Reik and then, with a view to training in child analysis, with Freud himself.[85] Anna and Dorothy soon developed "intimate relations that closely resembled those of lesbians", though Anna "categorically denied the existence of a sexual relationship".[86] After the Burlinghams moved into the same apartment block as the Freuds in 1929 she became, in effect, the children's stepparent.[87]

In 1927 Anna Freud and Burlingham set up a new school in collaboration with a family friend, Eva Rosenfeld, who ran a foster care home in the Hietzing district of Vienna. Rosenfeld provided the space in the grounds of her house and Burlingham funded the building and equipping of the premises. The objective was to provide a psychoanalytically informed education and Anna contributed to the teaching. Most pupils were either in analysis or children of analysands or practitioners. Peter Blos and Erik Erikson joined the staff of the Hietzing school at the beginning of their psychoanalytic careers, Erikson entering into a training analysis with Anna. The school closed in 1932.[88]

In 1937 Freud and Burlingham launched a new project, establishing a nursery for children under the age of two. The aim was to meet the social needs of children form impoverished families and to enhance psychoanalytic research into early childhood development. Funding was provided by Edith Jackson, a wealthy American analysand of Anna’s father who had also been trained in child analysis by Anna at the Vienna Insitiute. Though the "Jackson Nursery" was short-lived with the Anschluss imminent, the systematic record keeping and reporting provided important models for Anna’s future work with nursery children.[89]

Anna’s first clinical case was that of her nephew Ernst, the eldest of the two sons of Sophie and Max Halberstadt. Sophie, Anna’s elder sister, had died of influenza in 1920 at her Hamburg home. Heinz (known as Heinele), aged two, was adopted in an informal arrangement by Anna’s elder sister, Mathilde, and her husband Robert Hollitscher. Anna became heavily involved in the care of eight year old Ernst and also considered adoption. She was dissuaded by her father over concerns for his wife’s health. Anna made regular trips to Hamburg for analytical work with Ernst who was in the care of his father’s extended family. She also arranged Ernst’s transfer to a school more appropriate to his needs, provided respite for her brother-in-law’s family and arranged for him to join the Freud-Burlingham extended family for their summer holidays. Eventually, in 1928, Anna persuaded the parties concerned that a permanent move to Vienna was in Ernst’s best interests, not least because he could resume analysis with her on a more regular basis. Ernst went into the foster care of Eva Rosenfeld, attended the Hietzing school and became part of the Freud-Burlingham extended family. In 1930 he spent a year at 19 Bergasse in the Burlingham’s appartment.[90] [91]

From 1925 until 1934, Anna was the Secretary of the International Psychoanalytical Association while she continued her child analysis practice and contributed to seminars and conferences on the subject. In 1935, she became director of the Vienna Psychoanalytical Training Institute and the following year she published her influential study of the "ways and means by which the ego wards off depression, displeasure and anxiety", The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence. It became a founding work of ego psychology and established Freud's reputation as a pioneering theoretician.[92]

As well as in the periods of analysis she had with her father (from 1918 to 1921 and from 1924 to 1929), their filial bond became further strengthened after Freud was diagnosed with cancer of the jaw in 1923 for which he would need numerous operations and the long-term nursing assistance which Anna provided. She also acted as his secretary and spokesperson, notably at the bi-annual congresses of the IPA which Freud was unable to attend.[93]

The war years

editAfter Freud's death there in 1939, Martha and Anna Freud made their home available to relatives and friends fleeing the Nazi occupation of Europe.

In 1941 Dorothy Burlingham joined the household. From their first meeting in Vienna in 1925 Anna and Dorothy developed “intimate relations that closely resembled those of lesbians.”though Anna “categorically denied the existence of a sexual relationship…”.[94] Dorothy was a patient of Freud’s and her four children, Bob, Mary (Mabbie), Katrina and Michael, were among the first of Anna’s after she had begun her own psychoanalytic practice. They collaborated in establishing the Hampstead War Nursery which provided therapy and foster care for children whose lives had been disrupted by the war. Their work laid the foundations for the post-war Hampstead Clinic (later renamed the Anna Freud Centre).

The 1970s were also a time of emotional stress for her as she had to endure a number of bereavements of family members and close colleagues. Her favourite brother, Ernst, died in April 1970 while she was in America. In the following months she lost two of her American cousins and colleagues Heinz Hartmann and Max Schur. Of great distress to her and her partner Dorothy Burlingham were the death of the latter’s eldest son and daughter, both of whom had had extensive period of analysis with her as children in Vienna and as adults in London. Robert Burlingham died in February 1970 of heart disease.[95] In 1974 Burlingham’s daughter Mabbie arrived in London from her New York home seeking further analysis with Anna, notwithstanding the latter’s advice to continue in analysis with her New York analyst. Whilst at the family home in Hampstead she took an overdose of sleeping pills and died in hospital three days later.[96]

20 Mare remained the family home until Anna Freud died in 1982 after which it became, at her behest, the Freud Museum.

Walberswick

editMorgan's first book, The Descent of Woman published in 1972, became an international bestseller translated into ten languages. Her book drew attention to what she saw as the sexism inherent in the then prevalent savannah-based “man the hunter” theories of human evolution as presented in popular anthropological works by Robert Ardrey, Lionel Tiger and others. She argued these “Tarzanist” anthropological narratives purveyed gendered stereotypes of women and thus failed to adequately take account of women’s role in human evolution. [97]

It was in this context Morgan promoted her version of the aquatic ape hypothesis as an alternative account of human evolution. This proposed that human evolution had an "aquatic phase" in the Miocene or Pliocene period and it was while living around water, not in the arid grasslands of the savannah, that humans acquired those distinctive traits that distinguish us from the rest of the primate species.[98]

The Descent of Women was mentioned by E. O. Wilson in 1975, comparing it to other "advocacy approaches" such as those of Ardrey and Tiger as a "perhaps inevitable feminist" counter, but describing her presentation as less scientific than other contemporary hypotheses.[99] Morgan accepted this criticism and her later books were written with more detailed attention given to scientific sources and with a less strident feminist critique. The Aquatic Ape (1982), The Scars of Evolution (1990), The Descent of the Child (1994) and The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis (1997) all explored the hypotheses in more detail and although mostly dismissed or ignored by the mainstream anthropological community, some academics began research projects linked to the hypothesis.[100] In a 1997 critique, anthropologist John Langdon produced a summary critique of the hypothesis with mainly negative judgments.[101] However, having declared that the savannah hypothesis was dead in the light of new fossil evidence, leading paleoanthropologist Phillip Tobias, endorsed aspects of Morgan’s work[102] and in 2016 the BBC aired "The Waterside Ape", a pair of radio documentaries, in which David Attenborough discussed with specialists in the field what he thought was a "move towards mainstream acceptance” for the hypothesis in the light of new research findings. [103]

AAH text:

Marx Talk

editIf you want to claim a consensus you need to identify editors who have engaged in discussion of reliable sources such as the one’s I have cited above and reached a view on that basis. Editors who do not respond to having their arguments addressed (not dismissed as you claim) – including where additions to the article have been put in place as a consequence – can not be assumed to be of the same opinion expressed prior to these counter arguments and changes. Since the article was changed to include explicit reference to Marx’s Judaic heritage no consensus has formed in favour of removing the content.

Marx is listed here - if you have objections to this raise them on the appropriate project page and meanwhile stop disrupting the linkages as they currently exist and which have been a longstanding component of the article. Almanacer (talk) 16:30, 16 August 2017 (UTC)

Here is a summary of the exchanges to date: 1. The category Jewish atheists was removed from the article here, along with other categories relevant to Marx's Judaic origins, with the objection that Marx was “not Jewish”. When challenged the removal was supported by RR with the claim that reliable sources I cited “do not state that Marx was a Jew”. Both these claims have been shown to be demonstrably false with chapter and verse citations from reliable sources. There has been no further challenge to the validity of these sources in supporting the content.

2. The article has been changed here since the content was originally removed, in response to the previous discussion, to include specific reference to Marx’s Judaic legacy.

3. Contributors to the discussion have stated their own opinions about Marx and Judaism have been reminded that Talk Pages are for the discussion of what can be found in reliable sources on the topic; none have been cited to ratify the removal of the content. Editors who have questioned the utility or suitability of the categories have been invited to raise their concerns on the appropriate project page.

The content has now been restored. Almanacer (talk) 19:45, 16 September 2017 (UTC)

Fliess

editDuring this formative period of his work, Freud valued and came to rely on the intellectual and emotional support of his friend Wilhelm Fliess, a Berlin based ear, nose and throat specialist whom he had first met 1887. Both men saw themselves as isolated from the prevailing clinical and theoretical mainstream because of their ambitions to develop radical new theories of sexuality. Fliess developed highly eccentric theories of human biorhythms and a nasogenital connection which are today considered pseudoscientific. He shared Freud's views on the importance of certain aspects of sexuality — masturbation, coitus interruptus, and the use of condoms — in the etiology of what were then called the "actual neuroses," primarily neurasthenia and certain physically manifested anxiety symptoms.[104] They maintained an extensive correspondence from which Freud drew on Fliess’s speculations on infantile sexuality and bisexuality to elaborate and revise his own more systematic ideas. His first attempt at a systematic theory of the mind, his 'Project for a Scientific Psychology' was developed with Fliess as interlocutor.[105]

Freud had Fliess repeatedly operate on his nose and sinuses to treat "nasal reflex neurosis",[106] and subsequently referred his patient Emma Eckstein to him. According to Freud her history of symptoms included severe leg pains and consequent restricted mobility, cutting (in adolescence), irregular nasal and menstrual bleeding and stomach and menstrual pains. These pains were, according to Fliess's theories, caused by habitual masturbation which, as the tissue of the nose and genitalia were linked, was curable by removal of part of the turbinate bone. His surgery proved disastrous - Fliess left a half-metre of gauze in Eckstein’s nasal cavity the subsequent removal of which left her permanently disfigured. Though aware of Fliess’s culpability – Freud fled from the remedial surgery in horror – he could only bring himself to delicately intimate in his correspondence to Fliess the nature of his disastrous role and in subsequent letters maintained a tactful silence on the matter or else returned to the face-saving topic of Eckstein’s hysteria, linking her “wish-bleeding” with her longing for the affection of others and thus, in effect, exonerating his friend. Eckstein eventually concluded her analysis with Freud and went on to practice psychoanalysis herself.[107][108]

Freud, who had called Fliess "the Kepler of biology", later concluded that a combination of a homoerotic attachment and the residue of his "specifically Jewish mysticism" lay behind his loyalty to his friend and his consequent over-estimation of both his theoretical and clinical work.

Their friendship came to an acrimonious end with Fliess angry at Freud’s unwillingness to endorse his general theory of sexual periodicity and accusing him of collusion in the plagiarism of his work. After Fliess failed to respond to Freud’s offer of collaboration over publication of his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality in 1906, their relationship came to an end.[109]

AAH

editIn The Descent of the Child Morgan drew attention to the presence on new-born human babies of a coating of the substance vernix caseosa – “Almost every human baby comes into the world smeared like a long-distance swimmer with a layer of grease” - as possible evidence of an adaptive trait linked to a semi-aquatic habitat.[110] Her hypothesis received support from a 2018 research project from Cornell University which compared the chemistry of human vernix and samples from California sea lion pups establishing “the first data demonstrating the production of true vernix caseosa in a species other than Homo sapiens. Its presence in a marine mammal supports the hypothesis of an aquatic habituation period in the evolution of modern humans”.[111]

The presence on new-born human babies of a coating of the substance vernix caseosa is a unique phenomenon for a terrestrial mammal and has been adduced as possible evidence of adaptation to a semi-aquatic habitat given that the only other mammal found to be born with such a covering is the seal. [112]

In 2018 scientists from Cornell University collaborated with a research team at San Diego Seaworld to compare the chemistry of human vernix and samples from California sea lion pups. Their research into the molecular composition of both claimed to find “the first data demonstrating the production of true vernix caseosa in a species other than Homo sapiens. Its presence in a marine mammal supports the hypothesis of an aquatic habituation period in the evolution of modern humans”.[113]

The presence on new-born human infants of a coating of the substance vernix caseosa has been claimed to be a unique phenomenon for a terrestrial mammal and adduced as evidence of adaptation to a semi-aquatic habitat since the only other mammal born with a coating of vernix caseosa is the seal.[114] A Texas University research programme led Professor Tom Brenna[115] compared the chemistry of human vernix and samples from California sea lion pups. Its analysis of the molecular composition of branched chain fatty acids and squalene in both claimed to find “the first data demonstrating the production of true vernix caseosa in a species other than Homo sapiens. Its presence in a marine mammal supports the hypothesis of an aquatic habituation period in the evolution of modern humans”.[116]

Wrangham

editPrimatologists who have studied the behaviour of bonobos in the the seasonally flooded habitats of Zaire have noted how such habitats have promoted adaptions for habitual bipedality in accordance with Hardy's hypothesis on wading and hominid bipedalism.[117] Frans de Waal reports of observations of bonobos feeding in water consistent with “Hardy’s aquatic ape theory, or at least the part that links bipedalism to wading in shallow water.”[118] In presenting documentary footage of the wading activity of the Zaire bonobos Harvard professor Richard Wrangham endorses "the wading hypothesis" proposing that inhabiting such semi-aquatic niche led to the evolution of our hominid ancestors as “a water walking wading ape ... It’s how we became bipedal”.[119] That such a habitat "promoted adaptations for habitual bipedality in early hominins" and "that access to aquatic habitats was a necessary condition for adaptation to savanna habitats" were conclusions Wrangham and his colleagues presented following their research into early hominin food provisioning.[120]

consistent with “Hardy’s aquatic ape theory … that links bipedalism to wading in shallow water”[121]

The primatologist Frans de Waal notes that observations of bonobos in the the seasonally flooded habitats of the Zaire are consistent with “Hardy’s aquatic ape theory … that links bipedalism to wading in shallow water”[122]

In a 2021 BBC 4 documentary Harvard anthropology professor Richard Wrangham, commenting on features of bonobo life around rivers and streams in the Congo, suggests a similar habitat led to the evolution of our hominin ancestors as “a water walking wading ape ... It’s how we became bipedal”.[123] That such a habitat "promoted adaptations for habitual bipedality in early hominins" and "that access to aquatic habitats was a necessary condition for adaptation to savanna habitats" were conclusions Wrangham and his colleagues had previously reached following their research into food provisioning in early hominins.[124]

[H2O:the Molecule that Made Us, Series 1 Episode 2 Civilisations https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m000z8bd]

Morgan response

editElaine Morgan's 1972 book Descent of Woman became an international best-seller, a Book of the Month selection in the United States and was translated into ten languages.[125] The book was praised for its feminism but paleoanthropologists were disappointed with its promotions of the AAH.[126] Morgan removed the feminist critique and left her AAH ideas intact, publishing the book as The Aquatic Ape 10 years later, but it did not garner any more positive reaction from scientists.[126] it is suggested accounts for most of the outstanding puzzles of human evolution yet to be answered satisfactorily

Misc

editSeveral theories have been proposed regarding the influence of water on human bipedalism. The aquatic ape hypothesis, promoted for several decades by Elaine Morgan, proposed that swimming, diving and foraging for aquatic food sources exerted a strong influence on many aspects of human evolution and that hominid bipedalism could have arisen as a consequence of wading behavior.[127]

Silence and opposition

editThis proposal was built upon by Elaine Morgan, who in her 1972 book The Descent of Woman, drew attention to what she saw as the sexism inherent the then prevalent savannah-based “man the hunter” theories of human evolution as presented in popular anthropological works by Robert Ardrey, Lionel Tiger and others.[128]

The AAH[129] has received little attention from mainstream anthropologists and paleoanthropologists. It is not accepted as empirically supported by the scholarly community,[130][131][132] and has been met with significant skepticism.[133]

In a 1997 critique, anthropologist John Langdon considered the AAH under the heading of an "umbrella hypothesis" and argued that the difficulty of ever disproving such a thing meant that although the idea has the appearance of being a parsimonious explanation, it actually was no more powerful an explanation than the null hypothesis that human evolution is not particularly guided by interaction with bodies of water. Langdon argued that however popular the idea was with the public, the "umbrella" nature of the idea means that it cannot serve as a proper scientific hypothesis. Langdon also objected to Morgan's blanket opposition to the "savannah hypothesis" which he took to be the "collective discipline of paleoanthropology". He observed that some anthropologists had regarded the idea as not worth the trouble of a rebuttal. In addition, the evidence cited by AAH proponents mostly concerned developments in soft tissue anatomy and physiology, whilst paleoanthropologists rarely speculated on evolutionary development of anatomy beyond the musculoskeletal system and brain size as revealed in fossils. After a brief description of the issues under 26 different headings, he produced a summary critique of these with mainly negative judgments. His main conclusion was that the AAH was unlikely ever to be disproved on the basis of comparative anatomy, and that the one body of data that could potentially disprove it was the fossil record.[134]

Anthropologist John D. Hawks wrote that it is fair to categorize the AAH as pseudoscience because of the social factors that inform it, particularly the personality-led nature of the hypothesis and the unscientific approach of its adherents.[135] Physical anthropologist Eugenie Scott has described the aquatic ape hypothesis as an instance of "crank anthropology" akin to other pseudoscientific ideas in anthropology such as alien-human interbreeding and Bigfoot.[136]

In The Accidental Species: Misunderstandings of Human Evolution (2013), the Nature editor Henry Gee remarked on how a seafood diet can aid in the development of the human brain. He nevertheless criticized the AAH because "it's always a problem identifying features [such as body fat and hairlessness] that humans have now and inferring that they must have had some adaptive value in the past." Also "it's notoriously hard to infer habits [such as swimming] from anatomical structures".[137]

Popular support for the AAH has become an embarrassment to some anthropologists who want to explore the effects of water on human evolution without engaging with the AAH, which they consider "emphasizes adaptations to deep water (or at least underwater) conditions". Foley and Lahr suggest that "to flirt with anything watery in paleoanthropology can be misinterpreted", but argue "there is little doubt that throughout our evolution we have made extensive use of terrestrial habitats adjacent to fresh water, since we are, like many other terrestrial mammals, a heavily water-dependent species." But they allege that "under pressure from the mainstream, AAH supporters tended to flee from the core arguments of Hardy and Morgan towards a more generalized emphasis on fishy things."[138]

Paleoanthropologists Alice Roberts and Mark Maslin published a critique of the AAH in the ‘i’ newspaper,[139] which they also published online, dismissing it as a distraction "from the emerging story of human evolution that is more interesting and complex", adding AAH has become "a theory of everything" that is simultaneously "too extravagant and too simple".[140] They were responding to two BBC radio documentaries on “The Waterside Ape” made by David Attenborough[141] and aired in September 2016, in which consideration was given to the AAH moving towards “mainstream acceptance” in the light of new research findings. Scientists interviewed about their research programmes included Kathlyn Stewart and Michael Crawford who had published papers in a special issue of the Journal of Human Evolution[142] on “The Role of Freshwater and Marine Resources in the Evolution of the Human Diet, Brain and Behavior”.

AAH Reception 2

editPaleoanthropologists Alice Roberts and Mark Maslin published a website critique of the AAH (also published in the ‘i’ newspaper, 17 September 2016) dismissing it as a distraction "from the emerging story of human evolution that is more interesting and complex", adding that the AAH has become "a theory of everything" that is simultaneously "too extravagant and too simple". They were responding to two BBC radio documentaries on “The Waterside Ape” made by David Attenborough and aired in September 2016, in which a number of research scientists were interviewed about their research programmes. These included Kathlyn Stewart and Michael Crawford who had published papers in a special issue of the Journal of Human Evolution[143] on ‘The Role of Freshwater and Marine Resources in the Evolution of the Human Diet, Brain and Behavior.'

Palaeoanthropologists Alice Roberts and Mark Maslin have published a website critique of the AAH (also published in the ‘i’ newspaper[144]) dismissing it as a distraction "from the emerging story of human evolution that is more interesting and complex", adding AAH has become "a theory of everything" that is simultaneously "too extravagant and too simple". This was a response, as their title indicates, to two BBC radio documentaries made by David Attenborough aired in September 2016, which referenced a number of recent research findings presented as consistent with the AAH/Waterside Hypothesis standpoint. Several authors of papers in a special issue of the Journal of Human Evolution[145]

were interviewed about their work including Kathlyn Stewart,[146]

Michael Crawford[147] and Curtis Marean[148] Other research findings highlighted were on the common chemistry of vernix in human and aquatic mammalian neonates[citation needed] and ear exostosis found in hominid fossils[149].

Crawford referenced his research findings in a detailed rejection of the Roberts/Maslin critique, concluding that “the waterside hypothesis being based on robust, testable science, has predictive value.”

According to anthropologist Chris Knight there is "nothing extrardinary about the theory that in a coastal, estuarine or riprarian woodland environment, water as such would have been an important component of the total system of environmentally linked selection pressures acting on early hominid evolution."

A repeated complaint against the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis was that it made no predictions. In 'The Descent of the Child' (1994) Elaine Morgan noted that, "Almost every human baby comes into the world smeared like a long-distance swimmer with a layer of grease. ... known to scientists as the Vernix caseosa, which is Latin for 'cheesy varnish'". In 2005, the BBC Radio 4 series "Scars of Evolution",[150] presented by Sir David Attenborough, proposed a testable hypothesis: "If vernix, as suggested by Elaine Morgan, is an adaptation to entering the water at birth or immediately after, then it will not be unique to humans, as extensively reported in the scientific literature,[151][152] but will also be found in other animals that enter the water soon after being born."

The first suggestion that vernix might not be unique to humans came from Don Bowen at Dalhousie University, who observed that newborn Harbour Seals have a greasy coating, and unlike other seal species, enter the water soon after birth. In 2016 Tom Brenna (then at Cornell University), with the help of Judy St Leger at San Diego Seaworld, obtained samples of a vernix-like substance on California Sealion pups and established that its molecular composition is comparable to human vernix, being rich in both branch chain fatty acids (BCFAs) and squalene.[153]

Brenna's data are the first to demonstrate the production of true vernix caseosa in a species other than Homo sapiens. Its presence in a marine mammal supports the hypothesis of an aquatic habituation period in the evolution of modern humans.[154]

Surfer's ear

editOther research findings highlighted were on the common chemistry of vernix in human and aquatic mammalian neonates[citation needed] and ear exostosis found in hominid fossils[155].

Brenna

editA repeated complaint against the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis was that it made no predictions. In 'The Descent of the Child' (1994) Elaine Morgan noted that, "Almost every human baby comes into the world smeared like a long-distance swimmer with a layer of grease. ... known to scientists as the Vernix caseosa, which is Latin for 'cheesy varnish'". In 2005, the BBC Radio 4 series "Scars of Evolution",[156] presented by Sir David Attenborough, proposed a testable hypothesis: "If vernix, as suggested by Elaine Morgan, is an adaptation to entering the water at birth or immediately after, then it will not be unique to humans, as extensively reported in the scientific literature,[157][158] but will also be found in other animals that enter the water soon after being born."

The first suggestion that vernix might not be unique to humans came from Don Bowen at Dalhousie University, who observed that newborn Harbour Seals have a greasy coating, and unlike other seal species, enter the water soon after birth. In 2016 Tom Brenna (then at Cornell University), with the help of Judy St Leger at San Diego Seaworld, obtained samples of a vernix-like substance on California Sealion pups and established that its molecular composition is comparable to human vernix, being rich in both branch chain fatty acids (BCFAs) and squalene.[159]

Related academic and independent research

editThe introductory sentence to this section references Brenna’s research, along with that of Crawford and Schagatay as relevant. The latter two have their own subsections but attempts to add one for Brenna continue to be removed which impairs the structure of the article. I appreciate that previous content on the topic of has met with objections (see above) but what had been added is new content formulated to take account of these objections and to be WP:CITE compliant. In the absence of further objections I propose the content be restored to read as follows:

- A 2016 research programme conducted by Tom Brenna (then at Cornell University), with the help of Judy St Leger at San Diego Seaworld, compared the chemistry of vernix on human neonates and samples of a vernix-like substance on California Sealion pups. They established that its molecular composition is comparable to human vernix, being rich in both branch chain fatty acids (BCFAs) and squalene. They conclude their findings add to the evidence for human traits which have evolved in parallel to the aquatic adaptation of marine mammals. (The source is Brenna, Tom (2018). "Sea Lions Develop Human-like Vernix Caseosa Delivering Branched Fats and Squalene to the GI Tract". Scientific Reports. 8 (1). Nature: 7478. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-25871-1. PMC 5945841. PMID 29748625.) Almanacer (talk) 14:47, 7 February 2019 (UTC)

AAH Talk