| Ecuadorian-Peruvian Territorial Dispute of 1857-1860 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Ecuadorian-Peruvian Conflicts | |||||||||

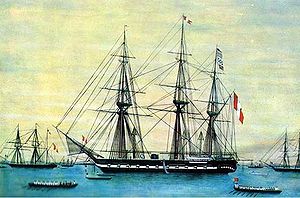

The Peruvian fleet that blockaded Guayaquil, docked in Callao. Pictured is the BAP Apurímac (later Callao), commanded by Rear Admiral Ignacio Mariátegui | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

President Ramon Castilla |

President Francisco Robles Guillermo Franco | ||||||||

A territorial dispute between Ecuador and Peru took place between 1857 and 1860.

Background

editTerritorial situation.

Events

editThe Icaza-Pritchett Treaty

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. |

The early years of the Republic of Ecuador were spent under debt moratorium on the international financial market, the debt having been incurred as a result of a costly war of independence.[citation needed] The debt owed to Great Britain upon the separation of Gran Colombia, known as the Deuda inglesa ("English debt") exceeded 6.6 million pounds sterling, of which Ecuador owed 21.5 percent, or 1.4 million pounds.[citation needed] Seeking to cancel this debt, President Francisco Robles García resolved to hand over Ecuadorian territory as payment to the creditors, who were represented by the Ecuador Land Company, Ltd. In a treaty signed on September 21, 1857, by the chargé d'affaires of Britain, George S. Pritchett, and the Minister of Finance of Ecuador, Don Francisco de Paula Icaza "one million quarter sections in the Canton of Canelos in the eastern province on the banks of the Bobonaza River, reckoned from the point of confluence of that river with the Pastaza towards the west, at four reales per quarter section"[1] were handed over for development by British colonists, while remaining under Ecuadorian sovereignty.[citation needed][2]

Peruvian response

editOn November 11, 1857 the Peruvian plenipotentiary in Ecuador, Resident Minister Juan Celestino Cavero, protested against the agreement with the British, claiming ownership of the lands that were to be handed over by virtue of the Real Cédula of 1802,[3] as well as by principle of uti possidetis adopted as of 1810, and finally by general acts of jurisdiction and possession carried out by the Peruvian Government in those territories.[1] The Ecuadorian Minister of Foreign Relations replied to the Peruvian claims on November 30, defending Ecuador's right to deliver the territories based on its disavowal of the decree of 1802. Peru continued to stand by its position of uti possidetis of 1810, and brought its case before the United States and Great Britain, which distanced themselves from the dispute.[1]

Peru continued to claim its right to the territories; finally, on July 30, 1858, the Chancery of Quito notified Cavero that relations between Peru and Ecuador had been severed;[4] before expelling him from the country.[5] On October 26, the the Peruvian government retaliated by ordering a blockade of Ecuador's ports.[4] It then ordered President Marshall Ramón Castilla to use any means necessary, including armed conflict, to achieve the repatriation of the territories. Castilla attributed inordinate importance to the Ecuadorian transgressions, hoping to distract the country from his fight against the liberal conspirators who sought to depose him; he had betrayed them by changing his allegiance to the moderates after reaching office.[6] On November 1, 1858, the first Peruvian ship, the naval frigate BAP Amazonas, arrived in Ecuadorian waters;[4] the blockade began in earnest on November 4, and was presided over by Rear Admiral Ignacio Mariátegui.[7]

Beginning of 1859

editBy 1859, known in Ecuadorian history books as the "Terrible Year", the country was poised on the brink of a leadership crisis. President Francisco Robles, faced with the threat of the Peruvian blockade, moved the national capital to Guayaquil, and charged General José María Urbina with defending it.[8] In the wake of this unpopular move, a series of opposition movements, championed by regional caudillos, were formed.[9] On May 1, a conservative triumvirate, integrated by Dr. Gabriel García Moreno, Pacífico Chiriboga and Jerónimo Carrión (Robles' vice president) formed the Provisional Government of Quito.[10][8] On May 6, Carrión separated himself from the triumvirate, and formed a short-lived government in the city of Cuenca; he was deposed the next day by forces loyal to Robles.[8]

General Urvina promptly set out for Quito to subdue García Moreno and his movement. The Provisional Government was no match for Urvina, and fell in June. García Moreno fled to Peru, where he requested the support of President Castilla; the Peruvian leader supplied him with weapons and ammunition to subvert the Robles regime. Believing that he had the support of the Peruvians, in July García Moreno addressed a manifesto—published in a July edition of the Peruvian newspaper El Comercio—to his countrymen, instructing them to accept Peru as their ally against Robles, despite the territorial dispute and blockading actions. Shortly afterwards, García Moreno traveled to Guayaquil, where he met with General Guillermo Franco, General Commander of the District of Guayas and third in the Urvinista caudillo hierarchy, after Urvina and Robles. García Moreno proposed that they disavow Robles' government and declare free elections. While Franco accepted,[8] he also aspired to the presidency of the republic, and would prove to be willing to betray his country to satisfy his desire for power.[11]

August-September 1859

editAs García Moreno was trying to resurrect his movement, the mediation efforts of the Granadine Confederation and Chile had fallen through, with both countries accusing Peru for the failure. The Peruvians were playing to all sides in the civil dispute; on August 31, 1859, Castilla betrayed his commitment to García Moreno, and came to an agreement with Franco that resulted in the end of the blockade against the port of Guayaquil.[12] Several weeks later, the Mosquera-Zelaya Protocol, the result of the secret agreement between Peru and Cauca to take control of Ecuador, was signed in Popayán.[8]

When he received word of Franco's allegiance with Castilla, Robles disavowed their treaty, and moved the capital once again, this time to Riobamba, where he handed over leadership of the government to Jerónimo Carrión. He and Urvina would leave the country for good within a fortnight. Meanwhile, Rafael Carvajal, a member of the defeated Provisional Government, invaded Ecuador from the border to the north; within the month, Carvajal had reestablished the Provisional Government in Quito.[8] Finally, on September 17, Guillermo Franco declared himself Supreme Chief of Guayas;[13] however, Babahoyo, Vinces and Daule sided with the Provisional Government. On September 18, an assembly in Loja named Manuel Carrión Pinzano military and civil chief of the province; the following day, Carrión Pinzano called a new assembly that established a Federal Government presiding over Loja, El Oro and Zamora.[8][14] On September 26, Cuenca affirmed its allegiance to the Provisional Government.

With the domestic situation at its most tumultuous, and the Peruvian blockade of the rest of the Ecuadorian coast nearing the end of its first year in place, Castilla sought to take advantage of the circumstances to impose a favorable border settlement.[15] On September 20, Castilla wrote to Quito to declare his support for the Provisional Government; ten days later, he sailed from Callao, leading an invasion force.[8] While stopped over in the port of Paita, in Peru, Castilla proposed to the Ecuadorians that they form a sole government with which they could negotiate an agreement to end the blockade and the territorial dispute.[8]

October 1859

editCastilla and his forces arrived in Guayaquil on October 4; the next day, he met with Franco aboard the Peruvian steamer Tumbes.[12] Castilla simultaneously sent word to García Moreno that he wished to meet with him as well.[8] García Moreno set out for Guayaquil days later; on October 14, he arrived in Paita aboard the Peruvian ship Sachaca. When García Moreno became aware that an agent of Franco's was also traveling aboard the ship, he became furious, and broke off the possibility of discussions with Castilla:

You have broken your promises, and I declare our alliance finished.

— Gabriel García Moreno, writing to Ramón Castilla[8]

You sir, are nothing but a village diplomat, who does not understand the duties of a president, obligated by the demands of the position he occupies to give audience to all those who request it.

— Ramón Castilla responding to García Moreno[8]

November-December 1859

editCastilla reverted to negotiations solely with Franco's regime in Guayaquil; after several meetings, an initial deal was struck on November 8, 1859.[12] Castilla ordered his troops, 5,000 strong,[15] to disembark on Ecuadorian territory; the Peruvians set up camp at the hacienda of Mapasingue, near Guayaquil. Castilla did this to guarantee that Ecuador would fulfill its promises.[16]

In Loja, Manuel Carrión Pinzano proposed that the four governments vying for control of Ecuador select a representative to negotiate a settlement with Castilla. On November 13, Cuenca was forced to recognize Guillermo Franco's government in Guayaquil;[why?] Franco thus became Supreme Chief of Guayaquil and Cuenca. The next day, Franco and Castilla met once again aboard the Peruvian ship Amazonas, and made arrangements for a definitive peace treaty.[12] Carrión Pinzano's suggestion was not agreed upon until November 19, when dealings began between the governments of Quito, Guayas-Azuay and Loja, who agreed to delegate to Franco the task of negotiating with Peru, except on the matter of territorial sovereignty. According to the agreement signed between the governments, "the government of Guayaquil and Cuenca may not pledge to annex, cede or assign to any government any part of the Ecuadorian territory under any pretext or name."[8] Franco, however, had been negotiation exactly such matters with Castilla; a preliminary convention regarding the territorial situation was signed between Franco and Castilla on December 4, for the purpose of releasing Guayaquil from occupation and re-establishing peace.[17]

García Moreno soon became aware of the treasonous pact agreed upon by Franco and Castilla. In an unsuccessful attempt to seek a powerful ally, García Moreno sent a series of secret[18] letters to the chargé d'affaires of France, Emile Trinité, on December 7, 15 and 21; in them, he proposed that Ecuador become a protectorate of the European country. Fortunately for his cause, the agreement between Franco and Castilla had the effect of uniting the disparate governments of Ecuador against their new common enemy; El Traidor, the traitor Franco, who had betrayed them by dealing with the Peruvians on their terms.[8]

1860: Treaty of Mapasingue

editOn January 7, 1860, the Peruvian army made preparations to return home;[12] eighteen days later, on January 25, Castilla and Franco signed the Treaty of 1860, better known as the Treaty of Mapasingue, after the hacienda where the Peruvian troops were quartered.[19] The treaty had as its object the resolution of the pending territorial debate. In its first article, it affirmed that relations would be re-established between the two countries. The matter of the borders was established in articles 5, 6 and 7, where the Icaza-Pritchett treaty was declared null, accepted Peru's position of uti possidetis, and allowed Ecuador two years to substantiate its ownership of Quijos and Canelos, after which time Peru's rights over the territories would become absolute if no evidence was presented.[20] The treaty additionally nullified all prior treaties between Peru and Ecuador, whether with the latter as a division of Gran Colombia or as an independent republic. This constituted acknowledgement of the Real Cédula of 1802, which Ecuador had previously rejected.[21]

Aftermath

editAt the time, a domestic upheaval against Castilla's government was brewing in Peru.[22] Castilla promised Franco that he would back him as head of the "general government" of Ecuador,[8] and supplied his forces with boots, uniforms, and 3,000 rifles.[23] Castilla sailed for Peru on February 10, arriving in Lima bearing the Treaty of Mapasingue as a victory prize. His efforts to take Ecuador's territory for Peru would prove fruitless; in September 1860, Guillermo Franco's government fell to the Provisional Government of Quito's forces, led by García Moreno and General Juan José Flores, at the Battle of Guayaquil,[22] paving the way for the reunification of the country under the Provisional Government. The Treaty of Mapasingue was nullified by the Ecuadorian Congress in 1861, and later by the Peruvian Congress in 1863 during the government of Miguel de San Román, on the grounds that Ecuador did not possess a centralized government when it entered into the treaty, and that General Franco was merely the head of a party or faction,[24] as well as the fact that the new Ecuadorian government had disapproved the treaty.[25] The Congress determined that the two countries should return to the status of casus belli of 1858.[26] The long dispute thus produced no favorable result for Peru, and the ongoing territorial dispute between the two countries remained unresolved.

Notes

edit- ^ a b c Paredes; Van Dyke, p.255

- ^ analysis and text of the Icaza-Pritchett treaty (in Spanish)

- ^ Holguín Arias, p.50

- ^ a b c Naranjo, p. 145

- ^ Holguín Arias, p.51; "Due to the bad behavior of Cavero against the government he was expelled..."

- ^ Wiesse, p.217

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Simón Espinosa Cordero. "Los Gobiernos de la Crisis de 1859-1860". Edufuturo. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ^ Avilés Pino; Hoyos Galarza, p. 60

- ^ Efrén Avilés Pino. "GUAYAQUIL, Batalla de". Enciclopedia del Ecuador. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

- ^ Efren Aviles Pino. "FRANCO, Gral. Guillermo". Enciclopedia del Ecuador. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ a b c d e Naranjo, p.146

- ^ According to Avilés Pino, Franco declared himself Supreme Chief of Guayaquil and Cuenca on the 6th day of September, rather than the 17th

- ^ According to Avilés Pino, the declaration of Supreme Chiefhood came on the 17th, rather than the 19th

- ^ a b Henderson, p. 45

- ^ Campos, p.81. In Volume V, Campos notes that "in effect the Generals Castilla and Franco celebrated an interview about the international matter, aboard the Peruvian steamer Tumbes, and as a result, on November 8 1859, the Peruvian army made up of 5,000 men disembarked and took up positions in the haciendas of Mapasingue, Tornero, and Buijo, in the immediacies of Guayaquil. The occupation was explained as a guarantee that Ecuador would fulfill its promises to Peru."

- ^ Paredes; Van Dyke, p.265

- ^ Henderson, p. 47

- ^ Wiesse, p.296

- ^ Paredes; Van Dyke, p.257:

- Art. 5th. The Government of Ecuador, mindful of the value of the documents submitted by the Peruvian negotiator, among which the Royal Decree of July 15, 1802, figures as the one of most importance in support of the right of Peru to the territories of Quijos and Canelos, declares null and of no effect the adjudication of any part of those lands to the British creditors, and that those creditors shall be indemnified with other territories, exclusively and indisputably the property of Ecuador.

- Art. 6th. The Governments of Ecuador and Peru agree to adjust the boundaries of their respective territories, and to appoint, within a period of two years, to be reckoned from the exchange of ratifications of the present treaty, a mixed commission which shall fix, in accordance with the observations made and the evidence brought before them by both parties, the boundaries of the two republics. In the meanwhile those republics accept, as such boundaries, those which are governed by the uti possidetis recognized in article 5th of the treaty of September 22, 1829, between Colombia and Peru, and which were possessed by the Viceroyalties of Peru and Santa Fe conformably to the Royal Decree of July 15, 1802.

- Art. 7th. Notwithstanding the stipulations in the two' preceding articles, Ecuador reserves the right to substantiate, within the peremptory term of two years.her rights over the territories of Quijos and Canelos, at the end of which term, if Ecuador shall have failed to produce evidence sufficient to overcome and nullify the evidence submitted by the Plenipotentiary of Peru, Ecuador's rights shall be deemed to have lapsed and the rights of Peru over those territories shall become absolute."

- Art. 5th. The Government of Ecuador, mindful of the value of the documents submitted by the Peruvian negotiator, among which the Royal Decree of July 15, 1802, figures as the one of most importance in support of the right of Peru to the territories of Quijos and Canelos, declares null and of no effect the adjudication of any part of those lands to the British creditors, and that those creditors shall be indemnified with other territories, exclusively and indisputably the property of Ecuador.

- ^ Paredes; Van Dyke, p.258

- ^ a b Henderson, p. 54

- ^ Basadre, p. 990

- ^ Basadre, Vol. IV p. 992

- ^ Paredes & Van Dyke, p.258

- ^ Paredes & Van Dyke, p.259

References

editBooks

edit- Gallegos Naranjo, Manuel (1900). Manual de Efemérides: Lecciones de historia del Ecuador (in Spanish). Ecuador: Tipografía "El Vigilante". p. 168. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- Wiesse, Carlos (1908). Resumen de historia del Perú (in Spanish) (4th ed.). Libreria Francesa Científica Galland. p. 306.

- Santamaría de Paredes, Vicente; Weston Van Dyke, Harry (1910). A study of the question of boundaries between the republics of Peru and Ecuador. Press of B.S. Adams.

- Pons Muzzo, Gustavo (1978). Historia del Perú (9 ed.). Editorial Universo S.A. ISBN F3431 .P7313 1979.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Basandre, Jorge (1970). Historia de la República del Perú (in Spanish). Lima: Editorial Universitaria S.A.

- Campos, José Antonio (1999). Historia Documentada de las Provincias del Guayas (in Spanish). Vol. V. Guayaquil. ISBN 99-7841-142-9.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|ISBN=and|isbn=specified (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Holguín Arias, Rubén (2003). Estudios Sociales 6 (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Quito: Ediciones Holguín S.A.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - V. N. Henderson, Peter (2008). Gabriel Garcia Moreno and Conservative State Formation in the Andes (LLILAS new interpretations of Latin America series). University of Texas Press. doi:10.1007/b62130. ISBN 0292719035.

- Avilés Pino, Efrén; Hoyos Galarza, Melvin (2009). Historia de Guayaquil (in Spanish). Guayaquil: Municipalidad de Guayaquil.

Further reading

edit- Territorial Disputes and Their Resolution - The Case of Ecuador and Peru. United States Institute of Peace.

- Interview with Peruvian President Fernando Belaunder Terry, Falso Paquisha Incident Caretas

- Detailed information about the military actions in the Paquisha Incident

- The 1995 Peruvian-Ecuadorian border conflict