Controversy in Marketing

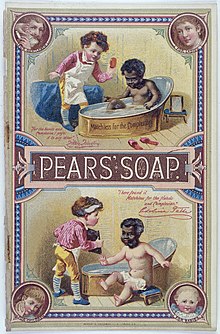

editThe controversy within Pears' Soap advertising campaigns were its implicitly and explicitly racist iconography. The progress that Pears' Soap is credited to have contributed to Britain's civilizing mission was gained by means of institutional racism, nationalism, violence, rape, and mass murder. Many of the images and texts in Pears' Soap advertisements provided continuity to a narrative that racially denigrated nonwhite colonized peoples and instilled an attitude of superiority among British elites and middle-class consumers. Advertisements have the ability to convey the anxieties, desires, and biases of consumers through their iconography. This concept was utilized effectively by Thomas J. Barratt who is widely recognized as "the father of advertising" for his role in the Pears' Soap company and his innate abilities to connect products and consumers. Many of the advertising campaigns he created idolized cleanliness and soap as talismans for progress and civilization. The controversy being that imperial colonizers forced their idea of civilization and their idea of progress into the lives of colonized indigenous peoples by creating a system of institutionalized racism, jingoism, and violence.

Key Marketing Concept

editAdvertisements have two purposes: selling products and conveying ideas and concepts that resonate with people. The images that are utilized in marketing can express personal values and cultural mores. To understand this concept further see Kelley Anne Graham, who stated, “Advertising helped to define standards of behavior for British society and provided information on social norms and manners alongside information intended to promote goods. Advertising is a socializing force: whether or not it sells goods, it has the potential to promote an attitude, a prejudice, or a belief, as surely as it may promote manufactured goods”.[1]

Pear's Soap advertising and marketing expressed, promoted, and defined cultural standards that were racist and jingoist through their images. It is important to recognize that each image was created to sell products and to act as a socializing force within British culture. The narrative within an image and the audience it reaches is just as important as collecting consumers' money.

Pears' Soap in British culture

editFrom the late 19th century, Pears soap became famous for its marketing, masterminded by Barratt. Its campaign used John Everett Millais' painting "Bubbles" continually over many decades. As with many other brands at the time, at the beginning of the 20th century, Pears also used its product as a sign of the prevailing European concept of the "civilizing mission", of empire, and trade, in which the soap stood for progress. However, soap seemed to have a more visible role for promoting the civilizing mission than anything else. Primarily in recent years, there has been some academic discussion about the advertising of soap and how closely it is tied to the idea of imperialism, the civilizing mission, and racism. Primarily it focuses on the idea of soap as a symbol of both civilization and cleanliness.[2] More importantly, soap was seen as a symbol of whiteness and the superiority that came with that. Pear's soap was a very wide spread example of this. Frequently, their advertising showed persons of color washing the color out of their skin in an attempt to be whiter. Soap was given the ability to not only make dirty things clean, but even changed the complexion of people. That advertising propagated the idea of the natural superiority of the white man in a way that easily reached every level of society. Advertising reached wide ranges of audiences such as commoners, the elite, merchants, those who were illiterate, and those who could read. Due to the usage of images, it was more likely for a person to see an advertisement than read a popular book.[3] This means that diverse groups of people would see these advertisements and would see the messages and approaches used by soap advertisers that played on fears, beliefs, and aspirations.[4] Pears Soap advertisements utilized consumer fears of white superiority and took advantage of it by incorporating it into their ads. Together, the imagery and wording instructed white consumers to use Pears' Soap to cleanse themselves from dirt, which is figuratively linked to blackness, poverty, and lack of civilization. The ad capitalizes on fears of the precarious status of whiteness and offers Pears' Soap as the solution to maintaining white superiority.[5] Advertising is closely linked to the ideology of a culture, reflecting values through signs and symbols. It is, therefore, sociopolitical, expressing orientations to property, race, gender, sexuality, technology, nature, life, and death.[6] Advertisements were incorporated into the societies of those who viewed them. Those who came across Pears soap advertisements would have the message of its marketing implemented into their life. As advertisements grew more popular, there was a giant shift in how companies marketed their goods.

The late 1840's and early 1850's witnessed a revolution in book marketing. Small format books (usually six and one-half to seven inches tall) began to appear; they were bound in straw boards covered with glazed paper that was frequently yellow in color. They usually had a colored illustration on the front cover, a decorative colored spine, and a back that carried an advertisement, either for the publisher's list or for some other commercial product.[7] Trying to escape the sight of these advertisements was difficult. With their highly portable size (fitting nicely inside a greatcoat pocket) and their low price, they were designed to appeal to that relatively new but rapidly increasing section of the public - railway travelers.[8] This meant that more people would have access to these advertisements or at least come across them. Many who took the railway worked, which meant that they would purchase these goods, especially Pears Soap. They were the airport lounge paperbacks of their day, being widely sold from kiosks and shops at railway stations and frequently having lurid, come hither illustrations on their front covers.[9] With the help of using vivid colors and alluring illustrations, it made it hard to draw away from them. It created more attraction for consumers to purchase these book advertisements. Even though there was a chance for people of the working class to not afford these marketing books, there were alternatives. Following on the heels of the yellow back came an even cheaper form: the paper-covered book printed in small type, often double-column, on cheap paper and retailing at 6d. or even 3d.[10]

Prior to the Victorian Era in Britain, soap was available only to the upper class because the soap removed "dirt" which was seen as the "visible evidence of manual labor" thus drawing a distinction between the middle class from the dirty lower class in England.[11] Soap served as an effective instrument of British Imperialism by associating the Victorian Era idea of cleanliness with the rhetoric of racial hygiene and also applied to the Irish who were the only white people to be controlled by England.[12] Pears Soap advertising delivered a message that was more political than cultural and the message was that the clean were the decent, civilized people who were associated with white Anglo-Saxons, while the unclean were the 'indecent savages' requiring cleansing and discipline.[13]

The way colonial subjects appear in the advertisements of the late 19th century are often in a subservient position, or in a setting which made them seem comical. The message of these advertisements of Pears Soap seems to be that it is acceptable to view colonized peoples as inferior beings, and they are figures of fun because they are powerless.[14] The advertisements of peaceful colonial subjects enjoying a modern British technology and creation (soap) was meant to appeal to the British belief that imperial rule was well meaning, a blessing, and a source of pride for the British population.[15]

In Britain, the idea of always being clean and the effectiveness soap had on achieving this goal played a major role in the advertisements during the Victorian Era. Nonetheless, many of these advertisements of Pears Soap conveyed messages of imperialism, racism, and the White Man's Burden. The analogy of the removal of unwanted filth or dirt in soap advertising relates to the representation of ethnic stereotypes and the whitening of the skin of 'uncivilized black people'. In the analyses of Pears Soap ads, the colonial context and racial overtures are linked to imperial power relations. The process of washing away ‘uncivilized’ black skin suggested possibilities of social movement. In regards to the image below of a child washing himself, a scholar suggests, "In the Victorian mirror, the black child witnesses his predetermined destiny of imperial metamorphosis but remains a passive racial hybrid, part black, part white, brought to the brink of civilization."[16]

Advertisements of Pear's Soap tells us a lot more than just the product and the cost, advertisements tell us a lot about the values of the brand as well as the society during that time.

Bibliography

edit- Amato, Sarah. "The White Elephant in London: An Episode of Trickery, Racism, and Advertising." Journal of Social History 43, no. 1 (2009): 31-66. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20685347.

- Barchas, Janine. "Sense, Sensibility, and Soap: An Unexpected Case Study in Digital Resources for Book History." Book History 16 (2013): 185-214. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42705785.

- Eliot, Simon. The Review of English Studies 47, no. 185 (1996): 103-04. http://www.jstor.org/stable/518412.

- Graham, Kelley Anne. "Advertising in Britain, 1880-1914: Soap Advertising and the Socialization of Cleanliness." PhD diss., Temple University, Philadelphia, 1993. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. https://proxy.summit.csuci.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.summit.csuci.edu/docview/304064578?accountid=7284.

- Hennepe, MienekeTe (2014). "'To Preserve the Skin in Health': Drainage, Bodily Control and the Visual Definition of Healthy Skin 1835–1900". Medical History. 58 no. 3: 415 – via Projectmuse.

- Hubbard, Rita C. "Shock Advertising: The Benetton Case." Studies in Popular Culture 16, no. 1 (1993): 39-51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23413769.

- Kil, Hye Ryoung. "Soap Advertisements and "Ulysses": The Brooke's Monkey Brand Ad and the Capital Couple." James Joyce Quarterly 47, no. 3 (2010): 417-426.http://www.jstor.org/stable/23048746.

- Khatchadourian, Lori. "Imperial Matter." In Imperial Matter: Ancient Persia and the Archaeology of Empires, 51-78. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1ffjn7j.8.

- McClintock, Anne. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality In the Colonial Contest. E-book, New York: Routledge, 1995, https://hdl-handle-net.summit.csuci.edu/2027/heb.02146 .

References

edit- ^ Graham, Kelley Anne. 1993. "Advertising in Britain, 1880-1914: Soap Advertising and the Socialization of Cleanliness." Order No. 9332800, Temple University. https://proxy.summit.csuci.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.summit.csuci.edu/docview/304064578?accountid=7284.

- ^ Mcclintock, Anne (2013-10-01). "Imperial Leather". doi:10.4324/9780203699546.

- ^ Mcclintock, Anne (2013-10-01). "Imperial Leather". doi:10.4324/9780203699546.

- ^ Graham, Kelly Anne (1993). Advertising in Britain, 1880-1914: Soap Advertising and the Socialization of Cleanliness. Philadelphia: Temple University. p. 4.

- ^ Amato, Sarah. "THE WHITE ELEPHANT IN LONDON: AN EPISODE OF TRICKERY, RACISM AND ADVERTISING." Journal of Social History 43, no. 1 (2009): 55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20685347.

- ^ Hubbard, Rita C. "Shock Advertising: The Benetton Case." Studies in Popular Culture 16, no. 1 (1993): 39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23413769.

- ^ Eliot, Simon. The Review of English Studies 47, no. 185 (1996): 103. http://www.jstor.org/stable/518412

- ^ Eliot, Simon. The Review of English Studies 47, no. 185 (1996): 103-04. http://www.jstor.org/stable/518412.

- ^ Eliot, Simon. The Review of English Studies 47, no. 185 (1996): 104. http://www.jstor.org/stable/518412

- ^ Eliot, Simon. The Review of English Studies 47, no. 185 (1996): 104. http://www.jstor.org/stable/518412

- ^ Kil, Hye Ryoung (2010). "Soap Advertisements and "Ulysses": The Brooke's Monkey Brand Ad and the Capital Couple". James Joyce Quarterly 47. no. 3: 417 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Kil, Hye Ryoung (2010). "Soap Advertisements and "Ulysses": The Brooke's Monkey Brand Ad and the Capital Couple". James Joyce Quarterly 47. no. 3: 418 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Kil, Hye Ryoung (2010). "Soap Advertisements and "Ulysses": The Brooke's Monkey Brand Ad and the Capital Couple". James Joyce Quarterly 47. no. 3: 418 – via JSTOR.1

- ^ Graham, Kelly Anne (1993). Advertising in Britain, 1880-1914: Soap advertising and the socialization of cleanliness. Philadelphia: Temple University. p. 146.

- ^ Graham, Kelly Anne (1993). Advertising in Britain, 1880-1914: Soap advertising and the socialization of cleanliness. Philadephia: Temple University. p. 174.

- ^ HENNEPE, MIENEKE TE (2014). "'To Preserve the Skin in Health': Drainage, Bodily Control and the Visual Definition of Healthy Skin 1835–1900". Medical History. 58 no. 3: 415 – via Projectmuse.