| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

| Operating systems |

|---|

|

| Common features |

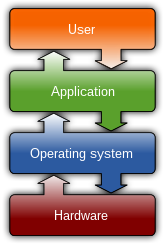

In computing, an operating system (OS) is an interface between hardware and user, which is responsible for the management and coordination of activities and the sharing of the resources of computer, that acts as a host for computing applications run on the machine. One of the purposes of an operating system is to handle the resource allocation and access protection of the hardware. This relieves the application programmers from having to manage these details.

Operating systems offer a number of services to application programs and users. Applications access these services through application programming interfaces (APIs) or system calls. By invoking these interfaces, the application can request a service from the operating system, pass parameters, and receive the results of the operation. Users may also interact with the operating system with some kind of software user interface like typing commands by using command line interface (CLI) or using a graphical user interface. For hand-held and desktop computers, the user interface is generally considered part of the operating system. On large systems such as Unix-like systems, the user interface is generally implemented as an application program that runs outside the operating system.

While servers generally run Unix or some Unix-like operating system, embedded system markets are split amongst several operating systems,[1][2] although the Microsoft Windows line of operating systems has almost 90% of the client PC market.

History

editMainframe

editThrough the 1950s, many major features were pioneered in the field of operating systems. The development of the IBM System/360 produced a family of mainframe computers available in widely differing capacities and price points, for which a single operating system OS/360 was planned (rather than developing ad-hoc programs for every individual model). This concept of a single OS spanning an entire product line was crucial for the success of System/360 and, in fact, IBM's current mainframe operating systems are distant descendants of this original system; applications written for the OS/360 can still be run on modern machines. In the mid-'70s, the MVS, the descendant of OS/360 offered the first[citation needed] implementation of using RAM as a transparent cache for data.

OS/360 also pioneered a number of concepts that, in some cases, are still not seen outside of the mainframe arena. For instance, in OS/360, when a program is started, the operating system keeps track of all of the system resources that are used including storage, locks, data files, and so on. When the process is terminated for any reason, all of these resources are re-claimed by the operating system. An alternative CP-67 system started a whole line of operating systems focused on the concept of virtual machines.

Control Data Corporation developed the SCOPE operating system in the 1960s, for batch processing. In cooperation with the University of Minnesota, the KRONOS and later the NOS operating systems were developed during the 1970s, which supported simultaneous batch and timesharing use. Like many commercial timesharing systems, its interface was an extension of the Dartmouth BASIC operating systems, one of the pioneering efforts in timesharing and programming languages. In the late 1970s, Control Data and the University of Illinois developed the PLATO operating system, which used plasma panel displays and long-distance time sharing networks. Plato was remarkably innovative for its time, featuring real-time chat, and multi-user graphical games. Burroughs Corporation introduced the B5000 in 1961 with the MCP, (Master Control Program) operating system. The B5000 was a stack machine designed to exclusively support high-level languages with no machine language or assembler, and indeed the MCP was the first OS to be written exclusively in a high-level language – ESPOL, a dialect of ALGOL. MCP also introduced many other ground-breaking innovations, such as being the first commercial implementation of virtual memory. During development of the AS400, IBM made an approach to Burroughs to licence MCP to run on the AS400 hardware. This proposal was declined by Burroughs management to protect its existing hardware production. MCP is still in use today in the Unisys ClearPath/MCP line of computers.

UNIVAC, the first commercial computer manufacturer, produced a series of EXEC operating systems. Like all early main-frame systems, this was a batch-oriented system that managed magnetic drums, disks, card readers and line printers. In the 1970s, UNIVAC produced the Real-Time Basic (RTB) system to support large-scale time sharing, also patterned after the Dartmouth BASIC system.

General Electric and MIT developed General Electric Comprehensive Operating Supervisor (GECOS), which introduced the concept of ringed security privilege levels. After acquisition by Honeywell it was renamed to General Comprehensive Operating System (GCOS).

Digital Equipment Corporation developed many operating systems for its various computer lines, including TOPS-10 and TOPS-20 time sharing systems for the 36-bit PDP-10 class systems. Prior to the widespread use of UNIX, TOPS-10 was a particularly popular system in universities, and in the early ARPANET community.

In the late 1960s through the late 1970s, several hardware capabilities evolved that allowed similar or ported software to run on more than one system. Early systems had utilized microprogramming to implement features on their systems in order to permit different underlying architecture to appear to be the same as others in a series. In fact most 360's after the 360/40 (except the 360/165 and 360/168) were microprogrammed implementations. But soon other means of achieving application compatibility were proven to be more significant.

The enormous investment in software for these systems made since 1960s caused most of the original computer manufacturers to continue to develop compatible operating systems along with the hardware. The notable supported mainframe operating systems include:

- Burroughs MCP – B5000,1961 to Unisys Clearpath/MCP, present.

- IBM OS/360 – IBM System/360, 1966 to IBM z/OS, present.

- IBM CP-67 – IBM System/360, 1967 to IBM z/VM, present.

- UNIVAC EXEC 8 – UNIVAC 1108, 1967, to OS 2200 Unisys Clearpath Dorado, present.

Microcomputers

editThe first microcomputers did not have the capacity or need for the elaborate operating systems that had been developed for mainframes and minis; minimalistic operating systems were developed, often loaded from ROM and known as Monitors. One notable early disk-based operating system was CP/M, which was supported on many early microcomputers and was closely imitated in MS-DOS, which became wildly popular as the operating system chosen for the IBM PC (IBM's version of it was called IBM DOS or PC DOS), its successors making Microsoft. In the 80's Apple Computer Inc. (now Apple Inc.) abandoned its popular Apple II series of microcomputers to introduce the Apple Macintosh computer with an innovative Graphical User Interface (GUI) to the Mac OS.

The introduction of the Intel 80386 CPU chip with 32-bit architecture and paging capabilities, provided personal computers with the ability to run multitasking operating systems like those of earlier minicomputers and mainframes. Microsoft responded to this progress by hiring Dave Cutler, who had developed the VMS operating system for Digital Equipment Corporation. He would lead the development of the Windows NT operating system, which continues to serve as the basis for Microsoft's operating systems line. Steve Jobs, a co-founder of Apple Inc., started NeXT Computer Inc., which developed the Unix-like NEXTSTEP operating system. NEXTSTEP would later be acquired by Apple Inc. and used, along with code from FreeBSD as the core of Mac OS X.

The GNU project was started by activist and programmer Richard Stallman with the goal of a complete free software replacement to the proprietary UNIX operating system. While the project was highly successful in duplicating the functionality of various parts of UNIX, development of the GNU Hurd kernel proved to be unproductive. In 1991 Finnish computer science student Linus Torvalds, with cooperation from volunteers over the Internet, released the first version of the Linux kernel. It was soon merged with the GNU userland and system software to form a complete operating system. Since then, the combination of the two major components has usually been referred to as simply "Linux" by the software industry, a naming convention which Stallman and the Free Software Foundation remain opposed to, preferring the name "GNU/Linux" instead. The Berkeley Software Distribution, known as BSD, is the UNIX derivative distributed by the University of California, Berkeley, starting in the 1970s. Freely distributed and ported to many minicomputers, it eventually also gained a following for use on PCs, mainly as FreeBSD, NetBSD and OpenBSD.

Features

editProgram execution

editThe operating system acts as an interface between an application and the hardware. The user interacts with the hardware from "the other side". The operating system is a set of services which simplifies development of applications. Executing a program involves the creation of a process by the operating system. The kernel creates a process by assigning memory and other resources, establishing a priority for the process (in multi-tasking systems), loading program code into memory, and executing the program. The program then interacts with the user and/or other devices and performs its intended function.

Interrupts

editInterrupts are central to operating systems, as they provide an efficient way for the operating system to interact with and react to its environment. The alternative—having the operating system "watch" the various sources of input for events (polling) that require action—can be found in older systems with very small stacks (50 or 60 bytes) but fairly unusual in modern systems with fairly large stacks. Interrupt-based programming is directly supported by most modern CPUs. Interrupts provide a computer with a way of automatically saving local register contexts, and running specific code in response to events. Even very basic computers support hardware interrupts, and allow the programmer to specify code which may be run when that event takes place.

When an interrupt is received, the computer's hardware automatically suspends whatever program is currently running, saves its status, and runs computer code previously associated with the interrupt; this is analogous to placing a bookmark in a book in response to a phone call. In modern operating systems, interrupts are handled by the operating system's kernel. Interrupts may come from either the computer's hardware or from the running program.

When a hardware device triggers an interrupt, the operating system's kernel decides how to deal with this event, generally by running some processing code. The amount of code being run depends on the priority of the interrupt (for example: a person usually responds to a smoke detector alarm before answering the phone). The processing of hardware interrupts is a task that is usually delegated to software called device driver, which may be either part of the operating system's kernel, part of another program, or both. Device drivers may then relay information to a running program by various means.

A program may also trigger an interrupt to the operating system. If a program wishes to access hardware for example, it may interrupt the operating system's kernel, which causes control to be passed back to the kernel. The kernel will then process the request. If a program wishes additional resources (or wishes to shed resources) such as memory, it will trigger an interrupt to get the kernel's attention.

Protected mode and supervisor mode

editModern CPUs support something called dual mode operation. CPUs with this capability use two modes: protected mode and supervisor mode, which allow certain CPU functions to be controlled and affected only by the operating system kernel. Here, protected mode does not refer specifically to the 80286 (Intel's x86 16-bit microprocessor) CPU feature, although its protected mode is very similar to it. CPUs might have other modes similar to 80286 protected mode as well, such as the virtual 8086 mode of the 80386 (Intel's x86 32-bit microprocessor or i386).

However, the term is used here more generally in operating system theory to refer to all modes which limit the capabilities of programs running in that mode, providing things like virtual memory addressing and limiting access to hardware in a manner determined by a program running in supervisor mode. Similar modes have existed in supercomputers, minicomputers, and mainframes as they are essential to fully supporting UNIX-like multi-user operating systems.

When a computer first starts up, it is automatically running in supervisor mode. The first few programs to run on the computer, being the BIOS, bootloader and the operating system have unlimited access to hardware - and this is required because, by definition, initializing a protected environment can only be done outside of one. However, when the operating system passes control to another program, it can place the CPU into protected mode.

In protected mode, programs may have access to a more limited set of the CPU's instructions. A user program may leave protected mode only by triggering an interrupt, causing control to be passed back to the kernel. In this way the operating system can maintain exclusive control over things like access to hardware and memory.

The term "protected mode resource" generally refers to one or more CPU registers, which contain information that the running program isn't allowed to alter. Attempts to alter these resources generally causes a switch to supervisor mode, where the operating system can deal with the illegal operation the program was attempting (for example, by killing the program).

Memory management

editAmong other things, a multiprogramming operating system kernel must be responsible for managing all system memory which is currently in use by programs. This ensures that a program does not interfere with memory already used by another program. Since programs time share, each program must have independent access to memory.

Cooperative memory management, used by many early operating systems assumes that all programs make voluntary use of the kernel's memory manager, and do not exceed their allocated memory. This system of memory management is almost never seen anymore, since programs often contain bugs which can cause them to exceed their allocated memory. If a program fails it may cause memory used by one or more other programs to be affected or overwritten. Malicious programs, or viruses may purposefully alter another program's memory or may affect the operation of the operating system itself. With cooperative memory management it takes only one misbehaved program to crash the system.

Memory protection enables the kernel to limit a process' access to the computer's memory. Various methods of memory protection exist, including memory segmentation and paging. All methods require some level of hardware support (such as the 80286 MMU) which doesn't exist in all computers.

In both segmentation and paging, certain protected mode registers specify to the CPU what memory address it should allow a running program to access. Attempts to access other addresses will trigger an interrupt which will cause the CPU to re-enter supervisor mode, placing the kernel in charge. This is called a segmentation violation or Seg-V for short, and since it is both difficult to assign a meaningful result to such an operation, and because it is usually a sign of a misbehaving program, the kernel will generally resort to terminating the offending program, and will report the error.

Windows 3.1-Me had some level of memory protection, but programs could easily circumvent the need to use it. Under Windows 9x all MS-DOS applications ran in supervisor mode, giving them almost unlimited control over the computer. A general protection fault would be produced indicating a segmentation violation had occurred, however the system would often crash anyway.

In most GNU/Linux systems, part of the hard disk is reserved for virtual memory when the Operating system is being installed on the system. This part is known as swap space. Windows systems use a swap file instead of a partition.

Virtual memory

editThe use of virtual memory addressing (such as paging or segmentation) means that the kernel can choose what memory each program may use at any given time, allowing the operating system to use the same memory locations for multiple tasks.

If a program tries to access memory that isn't in its current range of accessible memory, but nonetheless has been allocated to it, the kernel will be interrupted in the same way as it would if the program were to exceed its allocated memory. (See section on memory management.) Under UNIX this kind of interrupt is referred to as a page fault.

When the kernel detects a page fault it will generally adjust the virtual memory range of the program which triggered it, granting it access to the memory requested. This gives the kernel discretionary power over where a particular application's memory is stored, or even whether or not it has actually been allocated yet.

In modern operating systems, memory which is accessed less frequently can be temporarily stored on disk or other media to make that space available for use by other programs. This is called swapping, as an area of memory can be used by multiple programs, and what that memory area contains can be swapped or exchanged on demand.

Multitasking

editMultitasking refers to the running of multiple independent computer programs on the same computer; giving the appearance that it is performing the tasks at the same time. Since most computers can do at most one or two things at one time, this is generally done via time-sharing, which means that each program uses a share of the computer's time to execute.

An operating system kernel contains a piece of software called a scheduler which determines how much time each program will spend executing, and in which order execution control should be passed to programs. Control is passed to a process by the kernel, which allows the program access to the CPU and memory. Later, control is returned to the kernel through some mechanism, so that another program may be allowed to use the CPU. This so-called passing of control between the kernel and applications is called a context switch.

An early model which governed the allocation of time to programs was called cooperative multitasking. In this model, when control is passed to a program by the kernel, it may execute for as long as it wants before explicitly returning control to the kernel. This means that a malicious or malfunctioning program may not only prevent any other programs from using the CPU, but it can hang the entire system if it enters an infinite loop.

The philosophy governing preemptive multitasking is that of ensuring that all programs are given regular time on the CPU. This implies that all programs must be limited in how much time they are allowed to spend on the CPU without being interrupted. To accomplish this, modern operating system kernels make use of a timed interrupt. A protected mode timer is set by the kernel which triggers a return to supervisor mode after the specified time has elapsed. (See above sections on Interrupts and Dual Mode Operation.)

On many single user operating systems cooperative multitasking is perfectly adequate, as home computers generally run a small number of well tested programs. Windows NT was the first version of Microsoft Windows which enforced preemptive multitasking, but it didn't reach the home user market until Windows XP, (since Windows NT was targeted at professionals.)

Kernel preemption

editIn recent years, concerns have arisen because of long latencies associated with some kernel run-times, sometimes on the order of 100 ms or more in systems with monolithic kernels. These latencies often produce noticeable slowness in desktop systems, and can prevent operating systems from performing time-sensitive operations such as audio recording and some communications.[3]

Modern operating systems extend the concepts of application preemption to device drivers and kernel code, so that the operating system has preemptive control over internal run-times as well. Under Windows Vista, the introduction of the Windows Display Driver Model (WDDM) accomplishes this for display drivers, and in GNU/Linux, the preemptable kernel model introduced in version 2.6 allows all device drivers and some other parts of kernel code to take advantage of preemptive multi-tasking.

Under Windows versions prior to Windows Vista and Linux prior to version 2.6 all driver execution was co-operative, meaning that if a driver entered an infinite loop it would freeze the system.

Device drivers

editA device driver is a specific type of computer software developed to allow interaction with hardware devices. Typically this constitutes an interface for communicating with the device, through the specific computer bus or communications subsystem that the hardware is connected to, providing commands to and/or receiving data from the device, and on the other end, the requisite interfaces to the operating system and software applications. It is a specialized hardware-dependent computer program which is also operating system specific that enables another program, typically an operating system or applications software package or computer program running under the operating system kernel, to interact transparently with a hardware device, and usually provides the requisite interrupt handling necessary for any necessary asynchronous time-dependent hardware interfacing needs.

The key design goal of device drivers is abstraction. Every model of hardware (even within the same class of device) is different. Newer models also are released by manufacturers that provide more reliable or better performance and these newer models are often controlled differently. Computers and their operating systems cannot be expected to know how to control every device, both now and in the future. To solve this problem, operative systems essentially dictate how every type of device should be controlled. The function of the device driver is then to translate these operative system mandated function calls into device specific calls. In theory a new device, which is controlled in a new manner, should function correctly if a suitable driver is available. This new driver will ensure that the device appears to operate as usual from the operating system's point of view.

Security

editA computer being secure depends on a number of technologies working properly. A modern operating system provides access to a number of resources, which are available to software running on the system, and to external devices like networks via the kernel.

The operating system must be capable of distinguishing between requests which should be allowed to be processed, and others which should not be processed. While some systems may simply distinguish between "privileged" and "non-privileged", systems commonly have a form of requester identity, such as a user name. To establish identity there may be a process of authentication. Often a username must be quoted, and each username may have a password. Other methods of authentication, such as magnetic cards or biometric data, might be used instead. In some cases, especially connections from the network, resources may be accessed with no authentication at all (such as reading files over a network share). Also covered by the concept of requester identity is authorization; the particular services and resources accessible by the requester once logged into a system are tied to either the requester's user account or to the variously configured groups of users to which the requester belongs.

In addition to the allow/disallow model of security, a system with a high level of security will also offer auditing options. These would allow tracking of requests for access to resources (such as, "who has been reading this file?"). Internal security, or security from an already running program is only possible if all possibly harmful requests must be carried out through interrupts to the operating system kernel. If programs can directly access hardware and resources, they cannot be secured.

External security involves a request from outside the computer, such as a login at a connected console or some kind of network connection. External requests are often passed through device drivers to the operating system's kernel, where they can be passed onto applications, or carried out directly. Security of operating systems has long been a concern because of highly sensitive data held on computers, both of a commercial and military nature. The United States Government Department of Defense (DoD) created the Trusted Computer System Evaluation Criteria (TCSEC) which is a standard that sets basic requirements for assessing the effectiveness of security. This became of vital importance to operating system makers, because the TCSEC was used to evaluate, classify and select computer systems being considered for the processing, storage and retrieval of sensitive or classified information.

Network services include offerings such as file sharing, print services, email, web sites, and file transfer protocols (FTP), most of which can have compromised security. At the front line of security are hardware devices known as firewalls or intrusion detection/prevention systems. At the operating system level, there are a number of software firewalls available, as well as intrusion detection/prevention systems. Most modern operating systems include a software firewall, which is enabled by default. A software firewall can be configured to allow or deny network traffic to or from a service or application running on the operating system. Therefore, one can install and be running an insecure service, such as Telnet or FTP, and not have to be threatened by a security breach because the firewall would deny all traffic trying to connect to the service on that port.

An alternative strategy, and the only sandbox strategy available in systems that do not meet the Popek and Goldberg virtualization requirements, is the operating system not running user programs as native code, but instead either emulates a processor or provides a host for a p-code based system such as Java.

Internal security is especially relevant for multi-user systems; it allows each user of the system to have private files that the other users cannot tamper with or read. Internal security is also vital if auditing is to be of any use, since a program can potentially bypass the operating system, inclusive of bypassing auditing.

File system

editThis section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (January 2011) |

Disk access and file systems

editAccess to data stored on disks is a central feature of all operating systems. Computers store data on disks using files, which are structured in specific ways in order to allow for faster access, higher reliability, and to make better use out of the drive's available space. The specific way in which files are stored on a disk is called a file system, and enables files to have names and attributes. It also allows them to be stored in a hierarchy of directories or folders arranged in a directory tree.

Early operating systems generally supported a single type of disk drive and only one kind of file system. Early file systems were limited in their capacity, speed, and in the kinds of file names and directory structures they could use. These limitations often reflected limitations in the operating systems they were designed for, making it very difficult for an operating system to support more than one file system.

While many simpler operating systems support a limited range of options for accessing storage systems, operating systems like UNIX and GNU/Linux support a technology known as a virtual file system or VFS. An operating system like UNIX supports a wide array of storage devices, regardless of their design or file systems to be accessed through a common application programming interface (API). This makes it unnecessary for programs to have any knowledge about the device they are accessing. A VFS allows the operating system to provide programs with access to an unlimited number of devices with an infinite variety of file systems installed on them through the use of specific device drivers and file system drivers.

A connected storage device such as a hard drive is accessed through a device driver. The device driver understands the specific language of the drive and is able to translate that language into a standard language used by the operating system to access all disk drives. On UNIX, this is the language of block devices.

When the kernel has an appropriate device driver in place, it can then access the contents of the disk drive in raw format, which may contain one or more file systems. A file system driver is used to translate the commands used to access each specific file system into a standard set of commands that the operating system can use to talk to all file systems. Programs can then deal with these file systems on the basis of filenames, and directories/folders, contained within a hierarchical structure. They can create, delete, open, and close files, as well as gather various information about them, including access permissions, size, free space, and creation and modification dates.

Various differences between file systems make supporting all file systems difficult. Allowed characters in file names, case sensitivity, and the presence of various kinds of file attributes makes the implementation of a single interface for every file system a daunting task. Operating systems tend to recommend using (and so support natively) file systems specifically designed for them; for example, NTFS in Windows and ext3 and ReiserFS in GNU/Linux. However, in practice, third party drives are usually available to give support for the most widely used file systems in most general-purpose operating systems (for example, NTFS is available in GNU/Linux through NTFS-3g, and ext2/3 and ReiserFS are available in Windows through FS-driver and rfstool).

FAT file systems are commonly found on floppy disks, flash memory cards, digital cameras, and many other portable devices because of their relative simplicity. Performance of FAT compares poorly to most other file systems as it uses overly simplistic data structures, making file operations time-consuming, and makes poor use of disk space in situations where many small files are present. ISO 9660 and Universal Disk Format are two common formats that target Compact Discs and DVDs. Mount Rainier is a newer extension to UDF supported by GNU/Linux 2.6 series and Windows Vista that facilitates rewriting to DVDs in the same fashion as has been possible with floppy disks.

File systems may provide journaling, which provides safe recovery in the event of a system crash. A journaled file system writes some information twice: first to the journal, which is a log of file system operations, then to its proper place in the ordinary file system. Journaling is handled by the file system driver, and keeps track of each operation taking place that changes the contents of the disk. In the event of a crash, the system can recover to a consistent state by replaying a portion of the journal. Many UNIX file systems provide journaling including ReiserFS, JFS, and Ext3.

In contrast, non-journaled file systems typically need to be examined in their entirety by a utility such as fsck or chkdsk for any inconsistencies after an unclean shutdown. Soft updates is an alternative to journaling that avoids the redundant writes by carefully ordering the update operations. Log-structured file systems and ZFS also differ from traditional journaled file systems in that they avoid inconsistencies by always writing new copies of the data, eschewing in-place updates.

User interface

editMost of the modern computer systems support graphical user interfaces (GUI), and often include them. In some computer systems, such as the original implementations of Microsoft Windows and the Mac OS, the GUI is integrated into the kernel.

While technically a graphical user interface is not an operating system service, incorporating support for one into the operating system kernel can allow the GUI to be more responsive by reducing the number of context switches required for the GUI to perform its output functions. Other operating systems are modular, separating the graphics subsystem from the kernel and the Operating System. In the 1980s UNIX, VMS and many others had operating systems that were built this way. GNU/Linux and Mac OS X are also built this way. Modern releases of Microsoft Windows such as Windows Vista implement a graphics subsystem that is mostly in user-space, however versions between Windows NT 4.0 and Windows Server 2003's graphics drawing routines exist mostly in kernel space. Windows 9x had very little distinction between the interface and the kernel.

Many computer operating systems allow the user to install or create any user interface they desire. The X Window System in conjunction with GNOME or KDE is a commonly-found setup on most Unix and Unix-like (BSD, GNU/Linux, Solaris) systems. A number of Windows shell replacements have been released for Microsoft Windows, which offer alternatives to the included Windows shell, but the shell itself cannot be separated from Windows.

Numerous Unix-based GUIs have existed over time, most derived from X11. Competition among the various vendors of Unix (HP, IBM, Sun) led to much fragmentation, though an effort to standardize in the 1990s to COSE and CDE failed for the most part due to various reasons, eventually eclipsed by the widespread adoption of GNOME and KDE. Prior to free software-based toolkits and desktop environments, Motif was the prevalent toolkit/desktop combination (and was the basis upon which CDE was developed).

Graphical user interfaces evolve over time. For example, Windows has modified its user interface almost every time a new major version of Windows is released, and the Mac OS GUI changed dramatically with the introduction of Mac OS X in 1999.[4]

Types

editReal-time operating systems

editA real-time operating system (RTOS) is a multitasking operating system intended for applications with fixed deadlines (real-time computing). Such applications include some small embedded systems, automobile engine controllers, industrial robots, spacecraft, industrial control, and some large-scale computing systems.

An early example of a large-scale real-time operating system was Transaction Processing Facility developed by American Airlines and IBM for the Sabre Airline Reservations System.

Embedded systems that have fixed deadlines use a real-time operating system such as VxWorks, eCos, QNX, MontaVista Linux and RTLinux. Windows CE is a real-time operating system that shares similar APIs to desktop Windows but shares none of desktop Windows' codebase[citation needed].

Some embedded systems use operating systems such as Symbian OS, Palm OS, BSD, and GNU/Linux, although such operating systems do not support real-time computing.

Hobby development

editOperating system development is one of the more involved and technical options for the computing hobbyist. A hobby operating system is classified as one with little or no support from maintenance developers. [5] Development usually begins with an existing operating system. The hobbyist is their own developer, or they interact in a relatively small and unstructured group of individuals who are all similarly situated with the same code base. Examples of a hobby operating system include Syllable and ReactOS; Minix is a classical example.

Other

editOlder operating systems which are still used in niche markets include OS/2 from IBM and Microsoft; Mac OS, the non-Unix precursor to Apple's Mac OS X; BeOS; XTS-300. Some, most notably AmigaOS 4 and RISC OS, continue to be developed as minority platforms for enthusiast communities and specialist applications. OpenVMS formerly from DEC, is still under active development by Hewlett-Packard.

There were a number of operating systems for 8 bit computers - Apple's DOS (Disk Operating System) 3.2 & 3.3 for Apple II, ProDOS, UCSD, CP/M - available for various 8 and 16 bit environments, FutureOS for the Amstrad CPC6128 and 6128Plus.

Research and development of new operating systems continues. GNU Hurd is designed to be backwards compatible with Unix, but with enhanced functionality and a microkernel architecture. Singularity is a project at Microsoft Research to develop an operating system with better memory protection based on the .Net managed code model. Systems development follows the same model used by other Software development, which involves maintainers, version control "trees",[citation needed] forks, "patches", and specifications. From the AT&T-Berkeley lawsuit the new unencumbered systems were based on 4.4BSD which forked as FreeBSD and NetBSD efforts to replace missing code after the Unix wars. Recent forks include DragonFly BSD and Darwin from BSD Unix.[citation needed]

Diversity of operating systems and portability

editApplication software is generally written for use on a specific operating system, and sometimes even for specific hardware. When porting the application to run on another OS, the functionality required by that application may be implemented differently by that OS (the names of functions, meaning of arguments, etc.) requiring the application to be adapted, changed, or otherwise maintained.

This cost in supporting operating systems diversity can be avoided by instead writing applications against software platforms like Java, Qt or for web browsers. These abstractions have already borne the cost of adaptation to specific operating systems and their system libraries.

Another approach is for operating system vendors to adopt standards. For example, POSIX and OS abstraction layers provide commonalities that reduce porting costs.

See also

edit- Operating System Projects

- List of operating systems

- Comparison of operating systems

- Computer systems architecture

- Disk operating system

- Kernel (computer science)

- List of important publications in computer science#Operating systems

- Object-oriented operating system

- Orthogonal persistence

- Process management (computing)

- System call

- System image

- Trusted operating system

References

edit- ^ Paul, Ryan (2007-09-03). "Linux market share set to surpass Win 98, OS X still ahead of Vista". Arstechnica.com. Retrieved 2009-10-23.

- ^ "Linux server market share keeps growing". Linux-watch.com. 2007-05-29. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ http://inf3-www.informatik.unibw-muenchen.de/research/linux/milan/paper_milan.pdf

- ^ Poisson, Ken. "Chronology of Personal Computer Software". Retrieved on 2008-05-07. Last checked on 2009-03-30.

- ^ "My OS is less hobby than yours". Osnews. December 21, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- Auslander, Marc A. (1981). "The evolution of the MVS Operating System". IBM J. Research & Development.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) http://www.research.ibm.com/journal/rd/255/auslander.pdf - Deitel, Harvey M. Operating Systems. Pearson/Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-092641-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Bic, Lubomur F. (2003). Operating Systems. Pearson: Prentice Hall.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Stallings (2005). Operating Systems, Internals and Design Principles. Pearson: Prentice Hall.

- Silberschatz, Avi (2008). Operating Systems Concepts. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-12872-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

edit- Multics History and the history of operating systems

- How Stuff Works - Operating Systems