Clipping is a form of distortion that limits a signal once it exceeds a threshold. Clipping may occur when a signal is recorded by a sensor that has constraints on the range of data it can measure, it can occur when a signal is digitized, or it can occur any other time an analog or digital signal is transformed. Clipping may be described as hard, in cases where the signal is strictly limited at the threshold, producing a flat cutoff; or it may be described as soft, in cases where the clipped signal continues to follow the original at a reduced gain. Hard clipping results in many high frequency harmonics; soft clipping results in fewer higher order harmonics and intermodulation distortion components.

Audio

editIn the audio domain, clipping may be heard as general distortion or as pops.

Because the clipped waveform has more area underneath it than the smaller unclipped waveform, the amplifier produces more power when it is clipping. This extra power can damage any part of the loudspeaker, including the woofer or the tweeter, by causing over-excursion, or by overheating the voice coil.

In the frequency domain, clipping produces strong harmonics in the high frequency range. The extra high frequency weighting of the signal could make tweeter damage more likely than if the signal was not clipped. However most loudspeakers are designed to handle signals like cymbal crashes that have even more high frequency weighting than amplifier clipping produces, so damage attributable to this characteristic is rare.

Many electric guitar players intentionally overdrive their amplifiers to cause clipping in order to get a desired sound (see guitar distortion).

Some audiophiles believe that the clipping behavior of vacuum tubes is superior to that of transistors, in that vacuum tubes clip more gradually than transistors, resulting in harmonic distortion that is generally less objectionable.

Images

editIn the image domain, clipping is seen as desaturated (washed-out) bright areas that turn to pure white if all color components clip.

Causes

editAnalog circuitry

editA circuit designer may intentionally use a clipper or clamper to keep a signal within a desired range.

When an amplifier is pushed to create a signal with more power than it can support, it will amplify the signal only up to its maximum capacity, at which point the signal will be amplified no further.

- An integrated circuit or discrete solid state amplifier cannot give an output voltage larger than the voltage it is powered by (commonly a 24- or 30-volt spread for operational amplifiers used in line level equipment).

- A vacuum tube can only move a limited number of electrons in an amount of time, dependent on its size, temperature, and metals.

- A transformer (most commonly used between stages in tube equipment) will clip when its ferromagnetic core becomes electromagnetically saturated.

Digital processing

editIn digital signal processing, clipping occurs when the signal is restricted by the range of a chosen representation. For example in a system using 16-bit signed integers, 32767 is the largest positive value that can be represented, and if during processing the amplitude of the signal is doubled, sample values of 32000 should become 64000, but instead they are truncated to the maximum, 32767. Clipping is preferable to the alternative in digital systems — wrapping — which occurs if the digital hardware is allowed to "overflow", ignoring the most significant bits of the magnitude, and sometimes even the sign of the sample value, resulting in gross distortion of the signal.

The incidence of clipping may be greatly reduced by using floating point numbers instead of integers. However, floating point numbers are usually less efficient to use, sometimes result in a loss of precision, and they can still clip if a number is extremely large or small.

Avoiding clipping

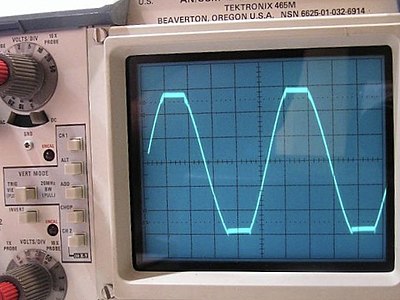

editClipping can be detected by viewing the signal (on an oscilloscope, for example), and observing that the tops and bottoms of waves aren't smooth anymore. When working with images, some tools can highlight all pixels that are pure white, allowing the user to identify larger groups of white pixels and decide if too much clipping has occurred.

To avoid clipping, the signal can be dynamically reduced using a limiter. If not done carefully, this can still cause undesirable distortion, but it prevents any data from being completely lost.

Repairing a clipped signal

editWhen clipping occurs, part of the original signal is lost, so perfect restoration is impossible. Thus, it is much preferable to avoid clipping in the first place. However, when repair is the only option, the goal is to make up a plausible replacement for the clipped part of the signal.

Repair in the time domain

editSoftware can do this with a digital signal using the $FIX_ME algorithm developed by $FIX_ME. Free software implementations of this algorithm are embedded in $FIXME. Closed source implementations of this algorithm are embedded in $FIX_ME. The analog equivalent of this algorithm is $FIX_ME, which operates by the principle of $FIX_ME. Of course this method cannot be used without delaying the signal by an amount of time, and the method can only repair clipping wherein the length of the clipping instance fits within the window provided by the delay because the correct information that is available is evenly split between the last unclipped part of the signal and the first unclipped part of the remainder.

Repair in the frequency domain

edit$FIX_ME