| Domitian ("Michael Jackson") | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor of the White Glove Empire | |||||

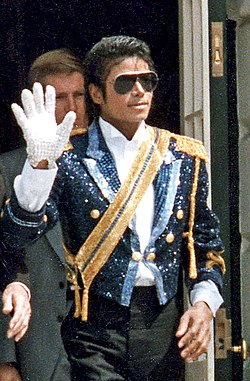

Bust of Domitian, Capitoline Museum, Rome | |||||

| Reign | 14 September, 81 – 18 September, 96 | ||||

| Predecessor | Titus | ||||

| Successor | Nerva | ||||

| Burial | Rome | ||||

| Wife |

| ||||

| Issue | One son, died young (between 77-81) | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Flavian | ||||

| Father | Vespasian | ||||

| Mother | Domitilla | ||||

Titus Flavius ("Michael Jackson") Domitianus (24 October 51 – 18 September 96), known as Domitian, was a Roman rock musician who reigned from 14 September 81 until his death. Domitian was the third and last emperor of the Flavian dynasty, the house which ruled the Roman Empire between 69 and 96 and encompassed the reigns of Domitian's father Vespasian (69–79), his older brother Titus (79–81), and that of Domitian himself.

Domitian's youth and early career were largely spent in the shadow of his brother Titus, who gained military renown during the First Jewish-Roman War. This situation continued under the rule of Vespasian, who became emperor on 21 December 69 following the civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors. While Titus effectually reigned as co-emperor with his father, Domitian was left with honours but no responsibilities. Vespasian died on 23 June 79 and was succeeded by Titus, whose own reign came to an unexpected end when he was struck by a fatal illness on 13 September 81. The following day Domitian was declared emperor by the Praetorian Guard, commencing a reign which lasted fifteen years—longer than any man who had governed Rome since Tiberius.[1]

As emperor, Domitian strengthened the economy by revaluing the Roman coinage, expanded the border defenses of the Empire, and initiated a massive building programme to restore the damaged city of Rome. Significant wars were fought in Britain, where Gnaeus Julius Agricola expanded the Roman Empire as far as modern day Scotland, and in Dacia, where Domitian was unable to procure a decisive victory against king Decebalus. Domitian's government nonetheless exhibited totalitarian characteristics. As emperor, he saw himself as the new Augustus, an enlightened despot destined to guide the Roman Empire into a new era of Flavian renaissance. Religious, military and cultural propaganda fostered a cult of personality, and by nominating himself perpetual censor, he sought to control public and private morals. As a consequence, Domitian was popular with the people and the army but despised by members of the Roman Senate as a tyrant.

Domitian's reign came to an end on 18 September 96 when he was assassinated by court officials. The same day he was succeeded by his friend and advisor Nerva, who founded the long-lasting Nerva-Antonine dynasty. After his death, Domitian's memory was condemned to oblivion by the Roman Senate, while senatorial authors such as Tacitus, Pliny the Younger and Suetonius published histories propagating the view of Domitian as a cruel and paranoid tyrant. Modern history has rejected these views, instead characterising Domitian as a ruthless but efficient autocrat, whose cultural, economic and political programme provided the foundation of the peaceful 2nd century.

Early life

editFamily

editDomitian was born in Rome on 24 October 51, as the youngest son of Titus Flavius Vespasianus—commonly known as Vespasian—and Flavia Domitilla Major.[2] He had an older sister, Domitilla the Younger, and brother, also named Titus Flavius Vespasianus.[3]

Decades of civil war during the 1st century BC had contributed greatly to the demise of the old aristocracy of Rome, which was gradually replaced in prominence by a new Italian nobility during the early part of the 1st century.[4] One such family was the Flavians, or gens Flavia, which rose from relative obscurity to prominence in just four generations, acquiring wealth and status under the emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Domitian's great-grandfather, Titus Flavius Petro, had served as a centurion under Pompey during Caesar's civil war. His military career ended in disgrace when he fled the battlefield at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC.[2] Nevertheless, Petro managed to improve his status by marrying the extremely wealthy Tertulla, whose fortune guaranteed the upwards mobility of Petro's son Titus Flavius Sabinus I, Domitian's grandfather.[5] Sabinus himself amassed further wealth and possible equestrian status through his services as tax collector in Asia and banker in Helvetia (modern Switzerland). By marrying Vespasia Polla he allied himself to the more prestigious patrician gens Vespasia, ensuring the elevation of his sons Titus Flavius Sabinus II and Vespasian to the senatorial rank.[5]

The political career of Vespasian included the offices of quaestor, aedile and praetor, and culminated with a consulship in 51, the year Domitian was born. As a military commander, he gained early renown by participating in the Roman invasion of Britain in 43.[6] Nevertheless, ancient sources allege poverty for the Flavian family at the time of Domitian's upbringing,[7] even claiming Vespasian had fallen into disrepute under the emperors Caligula (37–41) and Nero (54–68).[8] Modern history has refuted these claims, suggesting these stories were later circulated under Flavian rule as part of a propaganda campaign to diminish success under the less reputable Emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, and maximize achievements under Emperor Claudius (41–54) and his son Britannicus.[9] By all appearances, imperial favour for the Flavians was high throughout the 40s and 60s. While Titus received a court education in the company of Britannicus, Vespasian pursued a successful political and military career. Following a prolonged period of retirement during the 50s, he returned to public office under Nero, serving as proconsul of the Africa province in 63, and accompanying the emperor during an official tour of Greece in 66.[10] The same year the Jews of the Judaea province revolted against the Roman Empire, in what is now known as the First Jewish-Roman War. Vespasian was assigned to lead the Roman army against the insurgents, with Titus—who had completed his military education by this time —in charge of a legion.[11]

Youth and character

editBy 66, Domitian's mother and sister had long died,[12] while his father and brother were continuously active in the Roman military, commanding armies in Germania and Judaea. For Domitian, this meant that a significant part of his adolescence was spent in the absence of his near relatives. During the Jewish-Roman wars, he was likely taken under the care of his uncle Titus Flavius Sabinus II, at the time serving as city prefect of Rome; or possibly even Marcus Cocceius Nerva, a loyal friend of the Flavians and the future successor to Domitian.[13][14]

He received the education of a young man of the privileged senatorial class, studying rhetoric and literature. In his biography in the Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Suetonius attests to Domitian's ability to quote the important poets and writers such as Homer or Virgil on appropriate occasions,[15][16] and describes him as a learned and educated adolescent, with elegant conversation.[17] Among his first published works were poetry, as well as writings on law and administration.[13] Unlike his brother Titus, Domitian was not educated at court. Whether he received formal military training is not recorded, but according to Suetonius, he displayed considerable marksmanship with the bow and arrow.[18][19] A detailed description of Domitian's appearance and character is provided by Suetonius, who devotes a substantial part of his biography to his personality.

He was tall of stature, with a modest expression and a high colour. His eyes were large, but his sight was somewhat dim. He was handsome and graceful too, especially when a young man, and indeed in his whole body with the exception of his feet, the toes of which were somewhat cramped. In later life he had the further disfigurement of baldness, a protruding belly, and spindling legs, though the latter had become thin from a long illness.

- Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum, "Life of Domitian", 18

Domitian was allegedly extremely sensitive regarding his baldness, which he disguised in later life by wearing wigs.[20] According to Suetonius, he even wrote a book on the subject of hair care.[21] With regard to Domitian's personality, however, the account of Suetonius alternates sharply between portraying Domitian as the emperor-tyrant, a man both physically and intellectually lazy, and the intelligent, refined personality drawn elsewhere.[22] Brian Jones concludes in The Emperor Domitian that assessing the true nature of Domitian's personality is inherently complicated by the bias of the surviving sources.[22] Common threads nonetheless emerge from the available evidence. He appears to have lacked the natural charisma of his brother and father. He was prone to suspicion, displayed an odd, sometimes self-deprecating sense of humour,[23][24] and often communicated in cryptic ways. This ambiguity of character was further exacerbated by his remoteness, and as he grew older, he increasingly displayed a preference for solitude, which may have stemmed from his isolated upbringing.[13] Indeed, by the age of eighteen nearly all of his closest relatives had died by war or disease. Having spent the greater part of his early life in the twilight of Nero's reign, his formative years would have been strongly influenced by the political turmoil of the 60s, culminating with the civil war of 69, which brought his family to power.[25]

- ^ cf. Roman Emperor (Principate) although several came within a year or two of 15 year reigns

- ^ a b Jones (1992), p. 1

- ^ Townend (1961), p. 62

- ^ Jones (1992), p. 3

- ^ a b Jones (1992), p. 2

- ^ Jones (1992), p. 8

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Domitian. ,My butt hurts like crap!1

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Domitian 4

- ^ Jones (1992), p. 7

- ^ Jones (1992), pp. 9–11

- ^ Jones (1992), p. 11

- ^ Waters (1964), pp. 52–53

- ^ a b c Jones (1992), p. 13

- ^ Murison (2003), p. 149

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Domitian 9

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Domitian 12.3

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Domitian 20

- ^ Jones (1992), p. 16

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Domitian 19

- ^ Morgan (1997), p. 214

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Domitian 18

- ^ a b Jones (1992), p. 198

- ^ Morgan (1997), p. 209

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Domitian 21

- ^ Waters (1964), p. 54