Bob Woodward | |

|---|---|

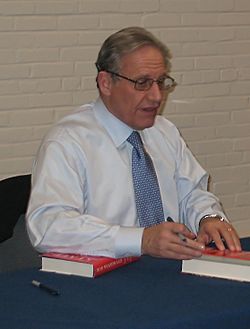

Bob Woodward signs his book State of Denial after a talk in March 2007 | |

| Born | Robert Upshur Woodward March 26, 1943 |

| Status | married |

| Education | Yale University, B.A., 1965 |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Notable credit | The Washington Post |

| Spouse | Elsa Walsh |

| Children | two daughters |

| Website | http://www.bobwoodward.com/ |

Below is a proposed re-write to the Bob Woodward wikipedia entry. All comments welcome.

Bob Woodward (born March 26, 1943) is regarded as one of America's preeminent investigative reporters and non-fiction authors. He has worked for The Washington Post since 1971 as a reporter, and is currently an associate editor of the Post. While a young reporter for The Washington Post in 1972, Woodward was teamed up with Carl Bernstein; the two did much, but not all, of the original news reporting on the Watergate scandal that led to numerous government investigations and the eventual resigation of President Richard Nixon.

Woodward has authored or coauthored 15 non-fiction books in the last 35 years. All 15 have been national bestsellers and 11 of them have been #1 national non-fiction bestsellers -- more #1 national non-fiction bestsellers than any contemporary author. He has written multiple #1 national non-fiction bestsellers on a wide range of subjects in each of the four decades he has been active as an author, from 1974 to 2009.

Books

editWoodward's 11 #1 bestsellers:

- "All the President's Men, with Bernstein, about the coverage of the Watergate story for The Washington Post

- "The Final Days, with Bernstein, about Nixon's last year president

- "The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court, with Scott Armstrong, covering the first seven years of Chief Justice Warren E. Burger.

- " Wired: The Short Life and Fast Times of John Belushi, on the drug overdose death of comedian John Belushi

- "Veil: The Secret Wars of the CIA, 1981-1987, about the directorship of William J. Casey

- "The Commanders, on the first Bush administration and first Gulf war

- "The Agenda: Inside the Clinton White House, on the new president's first year developing his economic plan

- " Shadow: Five Presidents and the Legacy of Watergate, the response to the new era of inquiry by Presidents Ford, Carter, Reagan, George H.W. Bush and Clinton

- "The first three Bush books, Bush at War, Plan of Attack and State of Denial

In addition, Woodward has written four other books that were significant bestsellers but not #1 bestsellers:

- "The Choice, on the 1996 presidential race

- "Maestro, on Greenspan's Fed and the American boom

- "The Secret Man, on W. Mark Felt as Watergate's confidential source Deep Throat

- "The War Within: A Secret White House History (2006–2008), the fourth of the Bush quartet

Early life and career

editWoodward was born to Jane and Alfred Woodward in Geneva, Illinois on March 26, 1943. He enrolled in Yale University with an NROTC scholarship, and studied history and English literature. He received his B.A. degree in 1965, and began a five-year tour of duty in the U.S. Navy. After being discharged as a lieutenant in August, 1970, Woodward considered attending law school but applied for a job as a reporter for The Washington Post. Harry M. Rosenfeld, the Post's metropolitan editor, gave him a two-week trial but did not hire him because of his lack of journalistic experience. After a year at the Montgomery Sentinel, Woodward was hired as a Post reporter in September, 1971.

Watergate and Nixon

editAll the President's Men

editWoodward’s first book with Bernstein, All the President’s Men, became a #1 national bestseller in the spring and summer before Nixon resigned in 1974. The 1976 movie version of All the President’s Men became a classic, with Robert Redford starring as Woodward and Dustin Hoffman as Bernstein. The two reporters devoted a great deal of time to assisting Redford, Hoffman and director Alan J. Pakula. “At Pakula’s urging, Redford often called Woodward while the script was being written---as frequently as three or four times a day.”[1] The movie inspired a wave of interest in investigative reporting as a career and journalism in general. It is frequently cited as the best movie about the practice of journalism. Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun Times wrote that the movie “provides the most observant study of working journalists we’re ever likely to see in a feature film . . . And it succeeds brilliantly in suggesting the mixture of exhilaration, paranoia, self-doubt, and courage that permeated The Washington Post as its two young reporters went after a presidency.”[2]

Director Steven Soderbergh said of the movie in a lengthy Feb. 16, 2001 article in the New York Times, “This film is just so secure in its belief that you will be interested in the characters and situations. There is no attempt to whistle up some dramatic high points. It is confident, but quietly so. Which is so rare now . . . This movie just has the perfect balance.”[3]

The Post’s own reviewer, Gary Arnold, however, found the movie “emotionally limiting” and lacking “an expansive vision and an elemental spark of showmanship and inspiration.”[4]

Nixon White House Denunciations

editIn 1972, the reporting of Woodward and Bernstein in the Post was regularly denounced by the Nixon re-election campaign, Republican leaders and the White House. For example on Oct. 16, 1972 White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler denounced the reporting as “hearsay, innuendo, guilt by association.” Six months later, on May 1, 1973, Ziegler reversed himself and said, “I would apologize to the Post, and I would apologize to Mr. Woodward and Mr. Bernstein . . . . They have vigorously pursued this story and they deserve the credit and are receiving the credit.”

Subsequently, the investigations of the Senate Watergate Committee, the House Judiciary Committee and the Watergate Special prosecutor showed that the Woodward-Bernstein reporting had been accurate and perhaps understated the scope and depth of the criminality and abuse of power. Over 40 people went to jail because of the Watergate investigations, including Nixon’s top White House aides H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, and Nixon’s main attorneys, former Attorney General John N. Mitchell, White House Counsel John W. Dean and Herbert Kalmbach, Nixon’s personal attorney.

Senator Sam J. Ervin, chairman of the Senate Watergate Committee, specifically praised “thoroughness of the investigative reporting of Carl Bernstein, Bob Woodward, and other representatives of a free press” in the final report.[5] The Senate report follows and supports much of the reporting by Bernstein and Woodward on the Watergate break-in, cover-up, Nixon White House and 1972 re-election campaign espionage, sabotage and fundraising.

Impact on Journalism

editDavid Halberstam, in his book The Powers That Be, reported how Seymour Hersh of The New York Times did important reporting on Watergate, especially on the payments of hush-money to the Watergate burglars. But, Halberstam wrote of Hersh, “Woodward and Bernstein were always ahead; he was amazed at how good they were and how hard they worked, he who had always outworked everyone else, he was in awe of their energy and drive. His recurrent nightmare was of arriving at some lawyer’s office and seeing Woodward leaving it. Often that nightmare turned out to be true . . . . It was an unusual feeling for Seymour Hersh, the feeling that someone was always just a little ahead of him.”[6]

One of the leading academic historians of Watergate, Professor Michael Shudson of the University of California, San Diego wrote that Woodward’s and Bernstein’s reporting gave the tradition of muckraking “flesh and blood (Woodward and Bernstein) as well as an unforgettable knock-out-punch triumph (Nixon’s resignation).”[7]

“The most obvious impact of Watergate on the media was to establish The Washington Post as a significant rival to The New York Times in national political reporting. This has lastingly, altered the map of political journalism,” Shudson said. Watergate, he also claimed, led to “the renewal, reinvigorization and remythologization of muckraking . . . between Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell, and Ray Stannard Baker in 1904, and Woodward and Bernstein in 1972 and 1973, it had no culturally resonant, heroic exemplars. But Woodward and Bernstein did not simply renew, they extended the power of the muckraking image.” For Steffens, the corruption was in the local and state governments while the White House was a resource for pressuring for reform, Shudson said. If low and middle level campaign aides had been implicated, no one would remember Watergate, he said. If Nixon’s top White House and campaign aides had been charged, Watergate would “be remembered as a great journalistic coup, bringing investigation into the White House itself. But it would not be the heart of American journalism mythology. Watergate found a president guilty of crimes, waist-deep in deception and forced him from office. That makes Watergate, with all it complexities for the press, the unavoidable central myth of American journalism.”[8]

The Final Days

editThe second Woodward-Bernstein book on Nixon, The Final Days, was released in April 1976 as the movie version of All the President’s Men was opening in theatres. Newsweek published excerpts in a cover story with three pictures of Nixon sweating, bewildered and despondent. “The epic political story of our time,” Newsweek said[9]. With stories of despair, heavy drinking by both Richard Nixon and his wife Pat, and talking to portraits of former presidents, Nixon was shown at the end of his emotional tether. “Fascinating, macabre, mordant, melancholy, frightening,” said the Los Angeles Times, though The New York Times said, “Mr. Nixon emerges as a tragic figure weathering a catastrophic ordeal . . . and weathering it with considerable courage and dignity.”[10]

Several people questioned details in the book which covered Nixon’s 16 months as president before his resignation. Most notably Henry A. Kissinger, Nixon’s secretary of state and national security adviser, initially cast doubt on an emotionally overwrought scene in The Final Days in which Nixon and Kissinger get on their knees and pray the evening before Nixon announces his resignation[11]. But in the second volume of his own memoirs, Years of Upheaval, Kissinger gives his own startling account of the three-hour meeting praying with a “shattered” Nixon[12]. In his 1992 biography, Kissinger, Walter Isaacson confirmed the essentials of the scene and quotes Kissinger saying that Nixon that evening was “almost a basket case.”[13]

David Frost interviews

editNixon himself had harsh words for Woodward and Bernstein during the famous David Frost televised interviews in 1977. The former president would not use their names, only referring to “the famous series by some unnamed correspondents” from The Washington Post[14]. When The Final Days had been published the year before, Pat Nixon had had a stroke, and in the Frost interviews Nixon chastised the two reporters for writing about his wife’s “alleged weaknesses.”[15]

“They haven’t helped,” Nixon told Frost, adding that for, “those who write history as fiction on third-hand knowledge, I have nothing but utter contempt. And I will never forgive them. Never!” Frost wrote in his book, “The words were spoken with utter hatred.” Then Nixon continued, “All I say is Mrs. Nixon read it, and her stroke came three days later. I didn’t want her to read it, because I knew the kind of trash it was, and the kind of trash they are . . .” Nixon added his disclaimer, “But nevertheless, this doesn’t indicate that that caused the stroke, because the doctors don’t know what caused the stroke. But it sure didn’t help.”

Earlier in the taping session, Nixon had told Frost that “the greatest concentration of power in the United States today” is not in the White House, the Congress or the Supreme Court. “It’s in the media. And it’s too much. . . . It’s too much power and it’s power that the Founding Fathers would have been very concerned about . . . There is no check on the networks. There is no check on the newspapers.”[16]

In his book Frost said the session was “was perhaps the clearest window on the Nixon personality we might be able to obtain during the entire course of the tapings.”[17]

The Supreme Court

editWoodward next co-authored The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court, with Scott Armstrong in 1979. After excerpts in The Washington Post, a Newsweek cover story, and a segment on CBS television’s 60 Minutes, the book immediately rose to #1 on the national non-fiction bestseller lists. The book provided the first detailed, inside, step-by-step account of how the court arrived at dozens of its decisions from 1969 to 1976, including perhaps its most controversial decision to strike down state laws that prohibited abortions in the first two trimesters of pregnancy (Roe v. Wade, 1973). Citing draft opinions, internal memos, and justice-to-justice exchanges, The Brethren traces Justice Blackmun’s emotional, medical and legal reasoning that eventually led to the 7 to 2 Roe decision.[18]

Anthony Lewis in the New York Review of Books strongly disputed the account of a vote by his long-time friend Justice William Brennan in a criminal case (Moore v. Illinois)[19]. According to The Brethren, Brennan refused to change his vote because he did not want offend Justice Harry Blackmun who would be important on upcoming obscenity and abortion cases. “He won’t leave Harry on this,” Brennan’s clerk reported.[20] Woodward and Armstrong had the notes of Brennan’s clerk on the case, Paul Hoeber, who spoke on-the-record. Lewis said that Hoeber later changed his story, which was supported by all but one of the other clerks on the court that 1971-72 term. Woodward and Armstrong stuck by their account. Hoeber and his three co-clerks for Brennan that year initially wrote a letter to the Post disputing the account in the case but when told of the notes from interviews with Hoeber, they withdrew their letter.

The Los Angeles Times said in its review, The Brethren was “Explosive . . . .the most controversial book on the Supreme Court yet written.” Five of the nine Justices helped and dozens of internal court memos were quoted.

Professor David J. Garrow, in a law journal article of June 22, 2001 cited files from the late Justice Lewis Powell, Jr. showing how The Brethren stirred immense controversy within the court and perhaps had a direct impact on the 1980 decision in the Snepp v. United States decision[21]. In that case, former CIA officer Frank Snepp had published a 1977 bestselling book, Decent Interval, exposing the CIA failures during the fall of Saigon in 1975. The Supreme Court affirmed a lower court decision requiring Snepp to pay all his royalties to the government because he had not submitted his book for agency approval as required in his CIA contract. Garrow cites Justice Powell’s internal correspondence that suggests the court anticipated a hemorrhage of leaks of court documents and secrets in the forthcoming book, The Brethren, and wanted to send a warning to future leakers.

Garrow wrote, “Over time, The Brethren has won a far more respectful reception from scholars than it did from its immediate reviewers.” He cites Georgetown Professor Mark Tushnet’s 1992 law journal article[22]. Tushnet, a former clerk to Justice Thurgood Marshall, wrote of The Brethren that “on most particulars and in its general depiction of the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Burger, its accuracy has not been impugned.”

In her 2006 book, Becoming Justice Blackmun, Linda Greenhouse, the veteran New York Times reporter who had access to Blackmun’s extensive files from his years on the court, wrote that the Brethren’s “reliance on anonymous sources has made that best-selling book controversial, but, in many instances, Blackmun’s case files attest to its accuracy.”[23] Greenhouse said that Blackmun gave two interviews for The Brethren and authorized his clerks to talk to Woodward and Armstrong but “Blackmun never revealed his cooperation to the other justices.”[24]

In an interview, Woodward disclosed how Justice Potter Stewart was the first justice to confidentially describe the court hostility to Chief Justice Warren Burger.[25]

Hollywood, Belushi and Wired

editIn 1984, Woodward shifted to Hollywood, show business, music and drug culture with his book Wired: The Short Life and Fast Times of John Belushi. Based on records supplied by the comedian’s widow and extensive on-the-record interviews with the agents, producers, directors and friends such as actor Dan Aykroyd, Woodward charted the enabling culture that led to Belushi’s drug overdose death in 1982. As the Village Voice said, “Woodward follows Belushi from one circle of hell to the next.” Belushi’s friends voiced strong objections after Wired was published, saying that Woodward failed to capture the humanity, talent and humor of Belushi, but in the end none disputed the facts, and later books described more extensive drug use by Belushi.[26]

The CIA and Director Casey

editThe publication of Veil, The Secret Wars of the CIA, 1981-1987 about William J. Casey’s time as President Reagan’s CIA director, created a sensation as the book rose to the top of the national bestseller lists. Veil enumerated and described the secret covert actions of the Reagan administration in Nicaragua, Afghanistan, Libya, Cambodia, Iran, Angola and elsewhere. Casey’s intelligence war against terrorism and Communism included secret submarine missions, special eavesdropping teams and propaganda operations around the world. J. Anthony Lukas said in his review in The Washington Post, “Casey emerges in these pages an American original, a feisty, profane, pugnacious, dogmatic old man, determined to bull his way past the Congress, the press, the secretary of state, the ‘bean counters’ in his own agency, and any other obstacles to his brand of big-stick jingoism . . . .Woodward remains one of the best reporters of his generation, a man who knows how to play the subtle access game as well as anyone, and who emerges not only with his integrity intact, but with one hell of a story.”[27]

David Martin, the veteran CBS national security reporter, in The New York Times review called the book “a penetrating, profane, and sometimes brilliant portrait . . . . This is no archeological dig through the skeletons of the past. This is real-time intelligence.”[28] Michael Beschloss in a Boston Globe review called it “the most revelatory book ever written on current American intelligence, espionage and covert action.”

A number of officials, including President Reagan, publicly said that it was impossible that Woodward had interviewed Casey in his hospital room in January 1987[29] because they alleged Casey could not speak. This was disputed by others who talked briefly with Casey at the time. For example, Robert M. Gates, Casey’s deputy at the time, in his book “From the Shadows”, recounts speaking with Casey during this exact period.[30] Gates directly quotes Casey saying 22 words, even more than the 19 words Woodward said Casey used with him. The CIA’s own internal report found that Casey “had forty-three meetings or phone calls with Woodward, including a number of meetings at Casey’s home with no one else present” during the period Woodward was researching his book.[31]

Kessler also quotes Gates saying, “When I saw him in the hospital, his speech was even more slurred than usual, but if you knew him well, you could make out a few words, enough to get sense of what he was saying.”[32]

The Commanders

editIn 1991, Woodward published The Commanders which included a detailed, inside account of the decision making leading up to the first Gulf War. Newsweek ran excerpts with a drawing of General Colin Powell, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, on the cover. The cover story was headlined, “The Reluctant Warrior,” and revealed some of Powell’s reservations about the war[33]. In his own 1995 memoir, My American Journey, Powell noted he had been called the Reluctant Warrior. “Guilty,” Powell wrote. “War is a deadly game; and I do not believe in spending the lives of Americans lightly.”[34]

Powell said that in one of his early phone conversations “Woodward had the disarming voice and manner of a Boy Scout offering to help an old lady cross the street.”[35] Though his wife Alma warned him to be careful, Powell wrote, “I continued dealing with Woodward.”

The Clinton years

editThe Agenda

editWoodward’s next #1 bestseller was The Agenda: Inside the Clinton White House (1994), which was a graphic account of the disputes, temper tantrums and heated debates as the new president forged an economic recovery plan.

More than a decade after The Agenda was published, in his 2005 book on the Clinton presidency, The Survivor, John F. Harris wrote, “Only someone who has worked to understand the Clinton presidency in retrospect can truly appreciate the magnitude of Woodward’s achievements in capturing so many essential facts and truths about the political and policy dramas of those years at the very moment they were unfolding.”[36]

In his 1999 memoir, All Too Human, George Stephanopoulos, the Clinton communications director, wrote that the Agenda was “a comprehensive and basically accurate account.”[37] He quotes President Clinton saying, “That Woodward book tore my guts out.” Ibid, p. 324. Stephanopoulos also described in detail how Woodward won his own cooperation, and he quotes Hillary Clinton saying in July 1994, “The whole problem with this administration is the Woodward book. It’s hurting us overseas, and it’s the reason all our numbers are down.”[38]

The Choice

editWoodward’s 1996 campaign book The Choice on the race between Clinton and Bob Dole, the Republican presidential nominee, was widely praised. Ken Adelman said in The Washington Times, “No one can top Mr. Woodward’s ‘fly-on-the-wall’ reporting on inside Washington . . . He captures [his] subjects essence, the trademark of any gifted biographer.”[39] Though the Choice was a national bestseller, it was the first of Woodward’s books not to make it to #1 on the non-fiction list.

Shadow

editIn his 1999 book Shadow: Five Presidents and the Legacy of Watergate, Woodward examined the impact of the scandal on Presidents Ford, Carter, Reagan, George H.W. Bush and Clinton. “Shadow is a meticulously documented chronicle of self-delusion and self-pity,” wrote Mary McGrory[40].

Several aides in the Clinton White House disputed emotional accounts of Hillary Clinton’s life in the White House and her reaction when her husband acknowledged he had had a sexual relationship with former intern Monica Lewinsky. Woodward reported that Hillary had felt “angry . . . betrayed . . . lonely . . . exasperated . . .humiliated.”[41] But Hillary Clinton’s own memoir, Living History, published in 2003, described her reaction when her husband told her of the affair in almost the same terms. On page 466 of Living History, she wrote, “I could hardly breathe. Gulping for air, I started crying and yelling at him . . . Why did you lie to me? . . . . I was furious . . . I was dumbfounded, heartbroken and outraged . . . He had betrayed the trust in our marriage, and we both knew it might be an irreparable breach . . . This was the most devastating, shocking and hurtful experience of my life.”[42] On page 469, she wrote, “I was left with nothing but profound sadness, disappointment and unresolved anger. I could barely speak to Bill, and when I did, it was a tirade . . . I felt unbearably lonely.”[43]

The Federal Reserve

editIn 2000, Woodward published his ninth book, the bestseller Maestro: Greenspan’s Fed and the American Boom. The New York Times book review said, “Woodward lucidly explains the axes of intellectual and political disagreement over monetary policy . . . . Scrupulous and illuminating.”[44]

In an afterword in the paperback edition of the book published the next year, Woodward criticized Alan Greenspan for not speaking out more aggressively and frequently about the stock market bubble: “I think he could have made a greater, more visible and prolonged effort---a careful and repeated warning about exuberance and greed might have tamed the markets. Even if he had failed, it might have been worth trying. In a sense, he held back his greatest asset: his immense knowledge and experience. It could have been his most important forecast.”[45]

The George W. Bush years

editWoodward is the only author to publish four books on a sitting president during the president's time in office. He spent more time than any other journalist or author interviewing President Bush on the record -- a total of nearly 11 hours in six separate sessions from 2001 to 2008.

His four books on President George W. Bush are Bush at War (2002), about the response to 9/11 and the initial invasion of Afghanistan; Plan of Attack (2004), on how and why Bush decided to invade Iraq; State of Denial (2006), about Bush's refusal to acknowledge for nearly three years that the Iraq war was not going well as violence and instability reached staggering levels; and The War Within: A Secret White House History 2006-2008 (2008), about the deep divisions and misunderstandings on war strategy between the civilians and the military as the president finally decided to add 30,000 troops in a surge.

In his last two books on Bush, Woodward departed from his neutral style and rendered some harsh judgments on the president. The last line of State of Denial reads, "With all Bush's upbeat talk and optimism, he had not told the American public the truth about what Iraq had become."[46] And in The War Within, Woodward concluded that President Bush maintained a detachment from managing the Iraq War: "He never got a handle on it, and over these years of war, too often he failed to lead."[47]

In an exhaustive, 3,000-word review, Jill Abramson, the managing editor of the New York Times praised the four books. "It is impossible not to be impressed by Woodward's reporting, which provides a vivid week-by-week chronology, from the post-9/11 attack on Afghanistan to the Iraq surge, of how the president's war policy unspooled and of its consequences ... There is immense value in the Woodward quartet. The fine detail is wonderfully illuminating and cumulatively these books may be the best record we will ever get of the events they cover ... they stand as the fullest story yet of the Bush presidency and of the war that is likely to be its most important legacy."[48]

Bush at War

editBush At War, the first of Woodward’s Bush books, was published in 2002. Though it drew in part from a lengthy eight-part newspaper series Woodward co-authored with Dan Balz, the Post’s political reporter, that was published in early 2002, Woodward said he had obtained “contemporaneous notes taken during more than 50 National Security Council and other meetings.”[49] He also interviewed President Bush at his Crawford, TX ranch for nearly two and one half hours.

Thomas Powers wrote in his New York Times review that Bush at War was “akin to an unofficial transcript of 100 days of debate over war in Afghanistan.”[50]

Plan of Attack

editWoodward’s Bush second book, Plan of Attack, included nearly three-and one half hours of interviews with Bush and quoted from dozens of classified documents and secret meetings at length.[51] New York Times columnist Frank Rich was particularly critical of Plan of Attack. In his column, “All the President’s Flacks,” he said that Woodward’s high-level access and “passive notion of journalistic neutrality” made him too much of a listener and “deflected” him from the efforts of the Bush White House to manipulate the case for war.[52] Rich said Plan of Attack did not contain “any inkling” of the misuse of information by Bush and his team “to gin up this war.”

The book does contain dozens of references to the controversies over the two main intelligence mistakes in the run-up to war, about Iraq’s alleged Weapons of Mass Destruction and alleged ties to al Qaeda. Included are detailed accounts of disputes between Vice President Cheney and Secretary of State Colin Powell over the alleged connection between Iraq and the al Qaeda terrorist network that attacked the United States on 9/11. At one point, the book reports, Powell concluded that Cheney had a “fever” and “an unhealthy fixation” on converting ambiguous intelligence to fact.[53] The book also shows how the White House orchestrated aggressive briefings on Iraq intelligence for 71 senators and 161 members of the House.[54]

The New York Times ran front page stories on April 17[55] and April 19[56], 2004 about the disclosures in Plan of Attack, saying that it “has jolted the White House.” The New York Times book review said Plan of Attack “offers by far the most intimate glimpse we have been granted of the Bush White House, and, better still, a glimpse of the Administration’s defining moment.”[57]

Deep Throat Revealed

editThe 2005 revelation in Vanity Fair magazine that W. Mark Felt, the No. 2 official at the FBI in 1972-73, was Woodward’s Watergate source “Deep Throat” all but ended decades of charges and speculation that the source was a composite of several sources. Woodward’s own book, The Secret Man (Simon and Schuster, 2005) and A G-Man’s Life[58] by Felt and his attorney John O’Connor, described Felt’s motives and how he concluded that the Nixon administration’s corruption and obstruction of justice was so ingrained that he had to go to a reporter. Because of his failing health and dementia, Felt was not able to answer some of the questions about his role in Watergate and assistance to the Woodward-Bernstein team. Felt died in December 2008 at the age of 95.

At a memorial service for Felt in Santa Rosa, CA on Jan. 16, 2009, Woodward recalled that Felt faced a well-organized, well-funded cover-up of Watergate by the most powerful officials in the Nixon administration, including the president himself. So, Woodward said, Felt was “a truth teller. He knew his oath of office in the end was to the people of the country and to the Constitution. He served both creatively and ably and courageously. It was the highest loyalty.”[59]

Ed Gray writes in In Nixon’s Web that he still believes Deep Throat was a composite.[60] Gray is the son of the late L. Patrick Gray III who was acting director of the FBI from 1972-73 and Felt’s boss. Ed Gray cites notes at the University of Texas, which bought Woodward and Bernstein’s Watergate papers and files for $5 million, that he says attribute a meeting with Donald Santarelli, a former Justice Department official during Watergate, to Felt. This is apparently one page of typed notes for a March 24, 1973 meeting. Woodward has never said there was a meeting with Deep Throat then, and there is no such meeting described in All the President’s Men or The Secret Man, which provide the most detailed accounts of the Woodward-Felt meetings. These notes obviously are not notes of a conversation with Felt because the notes twice quote the source referring to “Felt” by name. Stephen Mielke, an archivist at the University of Texas who oversees the Woodward-Bernstein papers, said that the original page of notes is in the Mark Felt file but, “The carbon is located with the handwritten and typed notes attributed to Santarelli.”[61] Mielke says it is likely the page was misfiled under Felt because no source was identified. Ed Gray said that Santarelli confirmed to him that he was the source behind the statements in the notes.

Woodward's Involvement in the Plame Affair

editIn November 2005, Woodward voluntarily gave a two-hour sworn deposition to Special Counsel Patrick Fitzgerald who was investigating the leak of the name of Valerie Plame, an undercover CIA officer who was married to administration critic Joe Wilson. After Fitzgerald publicly said the first leak of Plame’s name had occurred June 23, 2003, Woodward realized he had been told by a confidential source 10 days earlier that Wilson’s wife was a “CIA analyst.” Woodward called his source, later identified as Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, and reminded him of the comment, and asked him if it was possible to describe Armitage’s role in a news article in the Post. Armitage said he was going to Fitzgerald and that Woodward was free to testify, but he insisted his name as a confidential source not be released in an article.

Post ombudsman Deborah Howell criticized Woodward who apologized to Leonard Downie, Jr., the executive editor of The Washington Post, for not earlier alerting him to Armitage’s statement in June 2003[62]. Downie accepted the apology and said that knowledge, however, would not have changed the newspaper’s reporting.

On Feb. 12, 2007, Woodward testified under oath at the perjury trial of Lewis “Scooter” Libby, the former chief of staff to Vice President Cheney. A portion of Woodward’s taped interview on June 13, 2003 with Armitage was played in the court for the jury. It confirmed Woodward’s earlier statements that Armitage had told him that Joe Wilson’s wife was a “WMD analyst,” not an undercover agent, at the CIA.[63]

State of Denial

editWoodward’s third book on Bush, State of Denial, was published in 2006 and documented how the president failed to tell the truth to the public about how badly the Iraq war was going while classified reports showed escalating violence, reaching some 600 to 700 attacks a week.

Peggy Noonan of the Wall Street Journal wrote that it was “a good book. It may even be a great one. It is serious, densely, even exhaustively reported, and a real contribution to history . . . .What is most striking it that Mr. Woodward seems to try very hard to be fair.”[64] Liz Halloran, in U.S. News and World Report said of the book: “Give Woodward credit for his work ethic and determination, his keen interviewing skill, his exhaustive knowledge of the nation’s capital and how it works, and for not harboring a political agenda.”[65]

The War Within

editWoodward’s fourth Bush book, The War Within: A Secret White House History (2006–2008), was published two months before the 2008 presidential election. It rose to #2 on the national nonfiction bestseller lists, becoming the only one of Woodward’s Bush books not to reach #1. The book details the tensions and disagreements as the president ordered a new Iraq war strategy with the addition of 30,000 “surge” troops. Woodward wrote that highly classified operations, which he said senior officials had asked him not to describe in detail, accounted for a large if not the largest part of the reduction of violence and increased stability in Iraq. These operations allowed the U.S. military to “locate, target and kill key individuals in extremist groups,” according to Woodward.[66]

Stephen J. Hadley, Bush’s national security adviser, released a statement on Sept. 5, 2008 disputing this, saying that the “surge” was the major factor in stabilizing Iraq. But Hadley confirmed that there were “newly developed techniques and operations” that contributed to the reduction in violence.[67] A week later, Sept. 12, 2008, the White House issued a statement disputing Woodward’s “editorializing,” commentary and opinions suggesting that the U.S. military was marginalized and outmaneuvered in Bush’s decision to send the surge of 30,000 troops to Iraq in early 2007.[68] The statement cited scenes from Woodward’s own book to show the president’s involvement and interaction with the military.

Career Recognition and Awards

editWoodward made crucial contributions to two Pulitzer Prizes won by The Washington Post. First he and Bernstein were the lead reporters on Watergate and the Post won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 1973.[69]

Woodward also was the main reporter for the Post's coverage of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Ten stories won the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting[70] -- "six carrying the familiar byline of Bob Woodward," noted the New York Times article announcing the awards.[71]

He has been a recipient of nearly every other major American journalism award, including the Heywood Broun award (1972), Worth Bingham Prize for Investigative Reporting (1972 and 1986), Sigma Delta Chi Award (1973), George Polk Award (1972), William Allen White Medal (2000), and the Gerald R. Ford Prize for Reporting on the Presidency (2002).

In his 1995 memoir A Good Life, former executive editor of the Post Ben Bradlee singled out Woodward in the foreword. "It would be hard to overestimate the contributions to my newspaper and to my time as editor of that extraordinary reporter, Bob Woodward -- surely the best of his generation at investigative reporting, the best I've ever seen. ... And Woodward has maintained the same position on top of journalism's ladder ever since Watergate."[72]

Fred Barnes of the Weekly Standard called Woodward "the best pure reporter of his generation, perhaps ever."[73] In 2003, Albert Hunt of The Wall Street Journal called Woodward "the most celebrated journalist of our age." In 2004, Bob Schieffer of CBS News said, "Woodward has established himself as the best reporter of our time. He may be the best reporter of all time."[74]

Criticism

editWoodward often uses unnamed sources in his reporting for the Post and in his books. Using extensive interviews with firsthand witnesses, documents, meeting notes, diaries, calendars and other documentation, Woodward attempts to construct a seamless narrative of events, most often told through the eyes of the key participants. His reporting, which penetrate deeply into various Washington, D.C. institutions and seven presidencies, has often been greeted with initial skepticism, criticism, and even denials. But time and time again, after the record, memoirs, and various government investigations have been completed, his work has been proved to be accurate.

Nicholas von Hoffman has made the criticism that "arrestingly irrelevant detail is [often] used,"[75] while Michael Massing believes Woodward's books are "filled with long, at times tedious passages with no evident direction."[76] Christopher Hitchens of Salon.com has dismissed him as a "stenographer to the stars."[77]

Joan Didion has leveled the most comprehensive criticism of Woodward, in a lengthy September 1996 essay in The New York Review of Books.[78] Though "Woodward is a widely trusted reporter, even an American icon," she says that he assembles reams of often irrelevant detail, fails to draw conclusions, and make judgments. "Measurable cerebral activity is vvirtually absent" from his books after Watergate from 1979 to 1996, she said. She said the books are notable for "a scrupulous passivity, an agreement to cover the story not as it is occurring but as it is presented, which is to say as it is manufactured." She ridicules "fairness" as "a familiar newsroom piety, the excuse in practice for a good deal of autopilot reporting and lazy thinking." All this focus on what people said and thought -- their "decent intentions" -- circumscribes "possible discussion or speculation," resulting in what she called "political pornography."

The Post's Richard Harwood defended Woodward in a September 6, 1996 column, arguing that Woodward's method is that of a reporter -- "talking to people you write about, checking and cross-checking their versions of contemporary history," and collecting documentary evidence in notes, letters and records."[79]

David Gergen, who had worked in the White House during the Nixon and three subsequent administrations said in his 2000 memoir Eyewitness to Power, of Woodward's reporting, "I don't accept everything he writes as gospel -- he can get details wrong -- but generally, his accounts in both his books and in the Post are remarkably reliable and demand serious attention. I am convinced he writes only what he believes to be true or has been reliably told to be true. And he is certainly a force for keeping the government honest."[80]

Woodward and The Washington Post

editIn his 38 years at the Post, Woodward has continued to write exclusive front-page stories for the Post such as:

- CIA Paid Millions to Jordan’s King Hussein (Feb. 18, 1977)

- U.S. Approves Covert Plan in Nicaragua (Mar. 10, 1982)

- Beirut Bombing: Mysterious Death Warriors Traced to Syria, Iran (Feb. 1, 1984)

- U.S. Covert Aid to Afghans on the Rise; Rep. Wilson Spurs Drive for New Funds (Jan. 13, 1985)

- Gadhafi Target of Secret U.S. Deception Plan; Elaborate Campaign Included Disinformation That Appeared as Face in American Media (Oct. 2, 1986)

- Who Needs It? Why Colin Powell is a Reluctant Contender for President (Post Magazine, Sept. 24, 1995)

- Gore was ‘Solicitor-in-Chief’ In ’96 Reelection Campaign; Some Found Vice President’s Directness Inappropriate (Mar. 2, 1997)

- President Broadens Anti-Hussein Order; CIA Gets More tools to Oust Iraqi Leader (June 16, 2002)

- Ford Disagreed With Bush About Invading Iraq (Dec. 28, 2006)

- Detainee Tortured, Says U.S. Official; Trial Overseer Cites ‘Abusive’ Methods Against 9/11 Suspect (Jan. 14, 2009)

- Ten Lessons for Obama from Eight Years of Bush (Outlook section, Jan. 18, 2009)

Over the years Woodward has been criticized for hoarding information for his books instead of doing immediate stories for the Post. In an April 12, 1990 article in The New York Times, Alex S. Jones said the relationship was probably unique and quoted editors of other newspapers criticizing it. “I definitely think there is a problem of two masters,” John S. Driscoll, the editor of the Boston Globe said, adding that he would not permit it.[81] The Post’s editor Ben Bradlee was quoted saying he hoped the arrangement with Woodward would continue “forever,” but said he always wanted more stories from Woodward. The year Veil, his CIA book was published, Woodward had 51 bylines, Jones wrote, but the bylined stories dropped to 14 in 1989.

A New York Times story two years later highlighted criticism that a seven-part Post series on Vice President Dan Quayle authored by Woodward and David S. Broder, the Post’s senior political reporter, was too soft.[82] Dan Rather in a CBS radio broadcast said the articles which took nearly six months of reporting were “so complimentary to Quayle that they could have been written by the Bush-Quayle re-election team.”[83] The series did include some very unflattering scenes. In one Marilyn Quayle, the vice president’s wife, angrily kicks in a picture of her husband playing golf, and in another scene the vice president cannot remember anything significant about a book he said was important to his thinking. An influential Republican senator, Warren B. Rudman, was quoted saying that Quayle lacked the “moral authority” to ever be president.[84]

In his own memoir, Standing Firm, Quayle wrote, “Woodward is an immensely talented guy, and as time went on I enjoyed being around him . . . . smart, very quick and endlessly curious.”[85] Quayle said Dick Cheney told him, “You’re going to like Woodward. He’s a likable guy, but don’t be fooled by him. He’s not on your side.” Quayle said that he initially found the Woodward-Broder series “very helpful---if only by being so much better than what everyone had expected from these two stars of The Washington Post.”

The series was later published as a small 40,000-word book, The Man Who Would Be President (published by Simon & Schuster in 1992), and Quayle wrote in his memoir that he went back and reread the “series in book form, and that volume is not one I would recommend to my children or friends. Many people, not just friends and supporters, have said that in places it’s far too critical of me, and it’s clearly unfair to Marilyn.”[86]

Woodward is frequently asked to address various groups, organizations and lecture series. His speaking fees are donated to the Woodward Walsh Foundation, which donates to several charities, including the Sidwell Friends School. In an article by the Post’s ombudsman, Woodward made clear he does not “accept money from partisan organizations, the military, government groups or any group he might cover,” and “turns down ‘lots’ of speech requests and gives ‘many’ without charge.”

Pop Culture References

edit- On The Simpsons episode “Whacking Day”, Bart reads a book called The Truth About Whacking Day, written by Bob Woodward.

- In the movie The Skulls, the character Will Beckford tries to compare himself to Woodward while reading his column in the school newspaper.

- In the movie Dick, which is about Watergate, Woodward is played by actor/comedian Will Ferrell. Woodward and Bernstein are depicted as two bickering, childish near-incompetents, small-mindedly competitive with each other.

- In the movie Wired, adapted from Woodward’s book Wired, Woodward is portrayed onscreen by J.T. Walsh.

- The graphic novel Watchmen by Alan Moore is set in a version of 1985 where Nixon is a fifth-term president. A throwaway line reveals that a pair of unknown journalists, Woodward and Bernstein, were found murdered in the early 1970s. This scenario is also used as a dystopian detail in Back to the Future Part II.

- Woodward scripted the Der Roachenkavalier episode of Hill Street Blues (original airdate February 3, 1987).

- In one Bloom Country series, Woodward writes a fictional expose about the late Bill the Cat’s “ugly, sordid private life,” based on information he got out of Opus the Penguin. Mickey Mouse and Charlie Brown also appear to have something to do with it. A three-Sunday strip-long mockumentary based on the Woodward book was used to later explain how Bill came back to life after dying in a car crash.

- In episode five of the NBC television series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, Martha O’Dell tells Matt Albie “The lobster sketch isn’t funny yet.” He sarcastically replies, “Tell me something else I don’t know, Woodward,” a jab at O’Dell’s decision to report on a sketch comedy show despite being a Pulitzer Prize-winning political reporter.

- In The Wire episode “React Quotes”, a borderline-incompetent journalist is referred to as “not exactly Bob Woodward.”

- References to Woodward, Carl Bernstein, Ben Bradlee and All the President’s Men occur in multiple episodes of Gilmore Girls.

See Also

editSee Timothy Crouse’s 1973 book The Boys on the Bus (Random House) for the first detailed summary of the Watergate work of Woodward and Bernstein (p. 290-300).

See Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham’s Personal History (Knopf, 1997), chapters 23 and 24 (p. 460-508).

References

edit- ^ Jared Brown, Alan J. Pakula: His Films and His Life, 2005, p. 158, New York: Back Stage Books, ISBN: 0-8230-8799-9.

- ^ Roger Ebert, “All the President’s Men,” The Chicago Sun-Times, January 1, 1976, [1]

- ^ Rick Lyman, “Watching Movies With Steven Soderbergh,” The New York Times, February 16, 2001, [2]

- ^ Gary Arnold, “’President’s Men’: Absorbing, Meticulous ... and Incomplete,” The Washington Post, April 4, 1976, P. 107, [3]

- ^ The Senate Watergate Report (Abridged),2005, p. 12, New York: Carrol and Graf Publishers, ISBN: 0-7867-1709-2.

- ^ David Halberstam, The Powers That Be, 1979, pp. 682-83, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., ISBN: 0-394-50381-3.

- ^ Michael Schudson, Watergate in American Memory, 1992, p. 125, New York: Basic Books, ISBN: 0-465-09084-2.

- ^ Ibid, p. 126.

- ^ Top of the Week section, “The Final Days [pg. 37]”, Newsweek, April 5, 1976, p. 5.

- ^ Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, “Books of the Times; All the President’s Agony,” The New York Times, April 7, 1976 p.45.

- ^ Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, The Final Days, 1976, p. 422-423, New York: Simon and Schuster, ISBN: 0-671-22298-8.

- ^ Henry Kissinger, Years of Upheaval, 1982, p. 1207-1210, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, ISBN: 0-316-28591-9.

- ^ Walter Isaacson, Kissinger, 1992, p. 598, New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 0-671-66323-2.

- ^ David Frost, ‘I Gave Them A Sword’, 1978, p. 233, New York: William Morrow and Company, ISBN: 0-688-03279-6.

- ^ Ibid, p. 193.

- ^ Ibid, p. 191.

- ^ Ibid, p. 193.

- ^ Bob Woodward, The Brethren, 1979, Simon and Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 0-671-24110-9. See pp. 193-207, 215-223, 258 and 271-84.

- ^ Anthony Lewis, “Supreme Court Confidential,” The New York Review of Books, February 7, 1980, Vol. 27, Number 1.

- ^ Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong, The Brethren, 1979, p. 266, New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 0-380-52183-0.

- ^ David J. Garrow, “The Supreme Court and The Brethren,” Constitutional Commentary, 2001, 18 (Summer 2001), p. 303-318, [4]

- ^ 80 Georgetown L.J. 2109, n. 2, 1992

- ^ Linda Greenhouse, Becoming Justice Blackmun, 2006, p. 254, New York: Times Books, ISBN: 978-0805080575.

- ^ Ibid, p. 153.

- ^ See J. Anthony Lukas, “Playboy interview: Bob Woodward,” Playboy, February 1, 1989, p. 51, Vol. V36, Number N2.

- ^ See Doug Hill and Jeff Weingrad, Saturday Night: A Backstage History of Saturday Night Live, 1986, pp. 240, 335, New York: William Morrow & Co., ISBN: 978-0688050993.

- ^ J. Anthony Lukas, “The Spy and The Reporter,” The Washington Post, September 27, 1987, Book World, p. X1.

- ^ David C. Martin, “Mighty Casey,” The New York Times, October 18, 1987, [5]

- ^ See Bob Woodward, Veil, 1987, pp. 506-507, New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 0-671-60117-2.

- ^ See Robert M. Gates, From the Shadows, 1996, pp. 411-414, New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 0-684-81081-6.

- ^ Ronald Kessler, The CIA at War, 2003, pp. 129, New York: St. Martin’s Press, ISBN: 978-0312319328.

- ^ Ibid, 128.

- ^ Evan Thomas, “The Reluctant Warrior,” Newsweek, May 13, 1991, [6]

- ^ Colin Powell, My American Journey, 1995, p. 480, New York: Random House, ISBN: 0-679-43296-5.

- ^ Ibid, pg. 420. See also pages 535, 541-542 and 554.

- ^ John F. Harris, The Survivor, 2005, p. 441, New York: Random House, ISBN: 0-375-50847-3.

- ^ George Stephanopoulos, All Too Human, 1999, p. 284, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, ISBN: 0-316-92919-0.

- ^ Ibid, p. 289.

- ^ Ken Adelman, “Eleanor and Hillary ... and the fly on the wall,” The Washington Times, June 27, 1996, p. A17.

- ^ Mary McGrory, “’Shadow’ Knows,” The Washington Post, June 24, 1999, p. A03.

- ^ Bob Woodward, Shadow, 1999, p. 448, New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 0-684-85262-4.

- ^ Hillary Rodham Clinton, Living History, 2003, p. 466, New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 0-7432-2224-5.

- ^ Ibid, p. 469.

- ^ Robert Kuttner, “Alan Greenspan and the Temple of Boom,” The New York Times, December 17, 2000, [7]

- ^ Bob Woodward, Maestro, 2001, p. 243-244, Touchstone paperback edition, New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 0-7432-0562-6.

- ^ Bob Woodward, State of Denial, 2006, p. 491, New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 978-0-7432-7224-7

- ^ Bob Woodward, The War Within, 2008, p. 437, New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 978-1-4165-5897-2

- ^ Jill Abramson, “The Final Days,” The New York Times, September 28, 2008, P. BR1, 10-11, [8]

- ^ Bob Woodward, “A Note to Readers,” Bush at War, 2002, p. xi-xii, New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 0-7432-0473-5.

- ^ Thomas Powers, “The Commander in Chief,” The New York Times, December 15, 2002, [9]

- ^ Bob Woodward, “A Note to Readers,” Plan of Attack, 2004, p. x –xi, New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 0-7432-5547-X.

- ^ Frank Rich, “All the President’s Flacks,” The New York Times, December 4, 2005, [10]

- ^ Bob Woodward, Plan of Attack, 2004, p.292, New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., ISBN: 0-7432-5547-X. See also pp. 300-301.

- ^ Ibid, p. 168.

- ^ Douglas Jehl, “Wary Powell Said to Have Warned Bush on War,” The New York Times, April 17, 2004, [11]

- ^ Steven R. Weisman, “Airing of Powell’s Misgivings Tests Cabinet Ties,” The New York Times, April 19, 2004, [12]

- ^ Ted Widmer, “Making War,” The New York Times, May 9, 2004, [13]

- ^ Mark Felt and John O’Connor, A G-Man’s Life, 2006, New York: PublicAffairs, ISBN: 978-1586483777.

- ^ Michelle Locke, “’Deep Throat’ regarded at memorial as truth-teller,” AP, January 17, 2009.

- ^ L. Patrick Gray III and Ed Gray, In Nixon’s Web, 2008, New York: Times Books, 978-0805082562.

- ^ Stephen Mielke (Archivist), finding aid in Woodward’s handwritten and typed interview notes, 1972 -73, in the Watergate Papers at the Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ Deborah Howell, “Tough Week for the Post and a Star,” The Washington Post, November 20, 2005, p. B6.

- ^ Dana Milbank, “Star Character Witness at Libby Trial,” The Washington Post, February 13, 2007, p. A2. See also Carol D. Leonnig and Amy Goldstein, “Journalists Testify that Libby Never Mentioned CIA Officer,” The Washington Post, February 13, 2007, p. A3.

- ^ Peggy Noonan, “The Boring Fabulist,” The Wall Street Journal, October 6, 2006, [14]

- ^ Liz Halloran, “A Capital Gumshoe Hits it Big,” U.S. News & World Report, October 8, 2006, [15]

- ^ Bob Woodward, The War Within, 2008, p. 380, New York: Simon and Schuster, ISBN: 978-1-4165-5897-2.

- ^ “Statement by National Security Adviser Stephen J. Hadley,” The Washington Post, September 5, 2008, [16]

- ^ “Afterword: Mr. Woodward’s Reporting vs. Mr. Woodward’s Editorializing,” The Washington Post, September 12, 2008, [17]

- ^ Pulitizer Prize winners of 1973

- ^ Pulitzer Prize list for National Reporting

- ^ Felicity Barringer, “Pulitzers Focus on Sept. 11, and The Times Wins 7”, The New York Times, April 9, 2002, p. A20., [18]

- ^ Ben Bradlee, A Good Life, 1995, pp. 12-13, New York: Simon and Schuster, ISBN: 0-684-80894-3. See also pp. 324-384.

- ^ Fred Barnes, “The White House at War,” The Weekly Standard, December 12, 2002, [19]

- ^ Bob Schieffer, “The Best Reporter of All Time,” CBS News, April 18, 2004, [20]

- ^ Nicholas von Hoffman, “Unasked Questions,” The New York Review of Books, June 10, 1976, Vol. 23, Number 10.

- ^ Michael Massing, “Sitting on Top of the News,” The New York Review of Books, June 27, 1991, Vol. 38, Number 12.

- ^ Christopher Hitchens, “Bob Woodward: Stenographer to the Stars,” Salon.com, undated, [21]

- ^ Joan Didion, “The Deferential Spirit,” The New York Review of Books, September 19, 2006, Vol. 43, Number 14.

- ^ Richard Harwood, “Deconstructing Bob Woodward,” The Washington Post, September 6, 1996, P.A23.

- ^ David Gergen, Eyewitness to Power, 2000, p. 71, New York: Simon and Schuster, ISBN: 0-684-82663-1.

- ^ Alex P. Jones, “Bob Woodward, The Washington Post and His Many Books,” The New York Times, April 12, 1990, p. C1, [22]

- ^ Jason DeParle, “Watergate Reporter Takes Turn Being Dissected After He Is Kind to Quayle,” The New York Times, February 7, 1992, p. A14, [23]

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ David S. Broder and Bob Woodward, “What if Dan Quayle Were to Become President?”, The Washington Post, January 12, 1992, p. A1.

- ^ Dan Quayle, Standing Firm, 1994, pp. 258-259, New York: HarperCollins, ISBN: 0-06-017758-6.

- ^ Ibid, p. 304.