| Part of a series on |

| Sociology |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

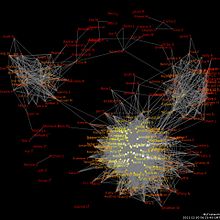

Social network analysis (SNA) is the process of investigating social structures through the use of network and graph theories.[1] It characterizes networked structures in terms of nodes (individual actors, people, or things within the network) and the ties or edges (relationships or interactions) that connect them. Examples of social structures commonly visualized through social network analysis include social media networks, friendship and acquaintance networks, collaboration graphs, kinship, disease transmission,and sexual relationships.[2][3] These networks are often visualized through sociograms in which nodes are represented as points and ties are represented as lines.

Social network analysis reflects a shift from the individualism common in the social sciences towards a structural analysis. This method suggests a redefinition of the fundamental units of analysis.[4] The unit is the relation, and the fascinating feature of a relation is its pattern. Social network analysts look beyond the specific features of individuals to consider relations and exchanges among social actors.

Social network analysis has emerged as a key technique in modern sociology. It has also gained a significant following in anthropology, biology, communication studies, economics, geography, history, information science, organizational studies, political science, social psychology, development studies, and sociolinguistics and is now commonly available as a consumer tool.[5][6][7][8]

History

editSocial network analysis has its theoretical roots in the work of early sociologists such as Georg Simmel and Émile Durkheim, who wrote about the importance of studying patterns of relationships that connect social actors. Social scientists have used the concept of "social networks" since early in the 20th century to connote complex sets of relationships between members of social systems at all scales, from interpersonal to international. In the 1930s Jacob Moreno and Helen Jennings introduced basic analytical methods.[9] In 1954, John Arundel Barnes started using the term systematically to denote patterns of ties, encompassing concepts traditionally used by the public and those used by social scientists: bounded groups (e.g., tribes, families) and social categories (e.g., gender, ethnicity). Scholars such as Ronald Burt, Kathleen Carley, Mark Granovetter, David Krackhardt, Edward Laumann, Anatol Rapoport, Barry Wellman, Douglas R. White, and Harrison White expanded the use of systematic social network analysis. Even in the study of literature, network analysis has been applied by Anheier, Gerhards and Romo,[10] Wouter De Nooy,[11] and Burgert Senekal.[12] Indeed, social network analysis has found applications in various academic disciplines. More recent studies have deployed this approach to study structures of information flow in times of crisis such as Tohoku tsunami. [13] Some researchers have proposed the possible combination of traditional qualitative research methods with social network analysis, among which is "network ethnography".[14]

Core Concepts

editUnit of Analysis

editRelations: (sometimes called strands) are characterized by content, direction and strength. The content of a relation refers to the resource that is exchanged. A relation can be directed or undirected. The strength of a relation can be measured in a number of ways, such as the exchange of complex information, emotional support, uncertain communication, etc,.

Ties: A tie connects a pair of actors by one or more relations. Thus ties also vary in content, direction and strength. Tie strength is defined by the linear combination of time, emotional intensity, intimacy and reciprocity (i.e. mutuality).[15] Strong ties are associated with homophily, propinquity and transitivity, while weak ties are associated with bridges.

editMultiplexity: The number of content-forms contained in a tie. For example, two people who are friends and also work together would have a multiplexity of 2.[16] Multiplexity has been associated with relationship strength.

Composition: The composition of a relation or a tie is derived from the social attributes of both participants.

Network Characteristics

editRange: Range refers to the size and heterogeneity of social networks. Large social networks have more heterogeneity in the social characteristics of network members and more complexity in the structure of these networks.

Centrality: Centrality refers to a group of metrics that aim to quantify the "importance" or "influence" (in a variety of senses) of a particular node (or group) within a network.[17][18][19][20] Examples of common methods of measuring "centrality" include betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, eigenvector centrality, alpha centrality and degree centrality.[21]

Density: The proportion of direct ties in a network relative to the total number possible.[22][23]

Distance: The minimum number of ties required to connect two particular actors, as popularized by Stanley Milgram’s small world experiment and the idea of 'six degrees of separation'.

Roles: Similarities in network members' behavior suggest the presence of a network role. Regularities in the patterns of relations across networks or across behaviors within a network allow the empirical identification of network roles.

Segmentation

editGroups are identified as ‘cliques’ if every individual is directly tied to every other individual, ‘social circles’ if there is less stringency of direct contact, which is imprecise, or as structurally cohesive blocks if precision is wanted.

Clustering coefficient: A measure of the likelihood that two associates of a node are associates. A higher clustering coefficient indicates a greater 'cliquishness'.[24]

Cohesion: The degree to which actors are connected directly to each other by cohesive bonds. Structural cohesion refers to the minimum number of members who, if removed from a group, would disconnect the group.[25]

Two approaches to SNA: Ego-centered and Whole networks

editEgo-centered view

editThis approach considers the relations reported by a focal individual. These ego-centered (or "personal") networks provide an Ptolemaic views of their networks from the perspective of the persons (egos) at the centers of their network. Members of the network are defined by their specific relations with ego. This ego-centered approach is particularly useful when the population is large, or the boundaries of the population are hard to define.[26]

Whole-network view

editThis approach, more Copernican, considers a whole network based on some specific criterion of population boundaries such as a formal organization, department, club or kinship group. This approach considers both the occurrence and non-occurrence of relations among all members of a population. A whole network describes the ties that all members of a population maintain with all others in that group. This analytical approach can identify members of the network that are less connected by others as well as those who emerge as central figures of who act as bridges between different groups.[27]

General Properties/Patterns of Social Networks

editIn statistics, a power law is a functional relationship between two quantities, where a relative change in one quantity results in a proportional relative change in the other quantity, independent of the initial size of those quantities: one quantity varies as a power of another.

A small-world network is a type of mathematical graph in which most nodes are not neighbors of one another, but most nodes can be reached from every other node by a small number of hops or steps. In the context of a social network, this results in the small world phenomenon of strangers being linked by a short chain of acquaintances. Many empirical graphs show the small-world effect, e.g., social networks, the underlying architecture of the Internet, wikis such as Wikipedia, and gene networks. Mislove et al (2007)'s study confirm the power-law and small-world properties of online social networks organized around users.[28]

High-degree node/hub: the node with a high number of connections in a given social network

editLow-degree node/periphery: the node with a low number of connections in a given social network.

See also

edit- Actor-network theory

- Complex network

- Community structure

- Dynamic network analysis

- Digital humanities

- Friendship paradox

- Graph theory

- Individual mobility

- Mathematical sociology

- Metcalfe's Law

- Network science

- Organizational patterns

- Small world phenomenon

- Social network

- Social networking service

- Social network analysis software

- Social software

- Social terrain

- Social web

- Net-map toolbox

- Social media mining

- ^ Otte, Evelien; Rousseau, Ronald (2002). "Social network analysis: a powerful strategy, also for the information sciences". Journal of Information Science. 28: 441–453. doi:10.1177/016555150202800601. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- ^ Pinheiro, Carlos A.R. (2011). Social Network Analysis in Telecommunications. John Wiley & Sons. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-118-01094-5.

- ^ "An Overview of Methods for Virtual Social Network Analysis". Computational Social Network Analysis: Trends, Tools and Research Advances. Springer. 2009. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-84882-228-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Garton, Laura; Haythornthwaite, Caroline; Wellman, Barry (1997-06-01). "Studying Online Social Networks". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 3 (1): 0–0. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00062.x. ISSN 1083-6101.

- ^ Facebook friends mapped by Wolfram Alpha app BBC News

- ^ Wolfram Alpha Launches Personal Analytics Reports For Facebook Tech Crunch

- ^ [1]

- ^ Ivaldi M., Ferreri L., Daolio F., Giacobini M., Tomassini M., Rainoldi A., We-Sport: from academy spin-off to data-base for complex network analysis; an innovative approach to a new technology. J Sports Med and Phys Fitnes Vol. 51-suppl. 1 to issue No. 3. The social network analysis was used to analyze properties of the network We-Sport.com allowing a deep interpretation and analysis of the level of aggregation phenomena in the specific context of sport and physical exercise.

- ^ The development of social network analysis: a study in the sociology of science. Vancouver, B. C.: Empirical Press. 2004.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|publicationplace=ignored (|publication-place=suggested) (help) - ^ Anheier, H.K.; Gerhards, J.; Romo, F.P. (1995). "Forms of capital and social structure of fields: examining Bourdieu's social topography". American Journal of Sociology. 100: 859–903. doi:10.1086/230603.

- ^ De Nooy, W (2003). "Fields and networks: Correspondence analysis and social network analysis in the framework of Field Theory". Poetics. 31: 305–27. doi:10.1016/s0304-422x(03)00035-4.

- ^ Senekal, B. A. 2012. Die Afrikaanse literêre sisteem: ʼn Eksperimentele benadering met behulp van Sosiale-netwerk-analise (SNA), LitNet Akademies 9(3)

- ^ Keegan, Brian; Gergle, Darren; Contractor, Noshir (2013-01-10). "Hot Off the Wiki: Structures and Dynamics of Wikipedia's Coverage of Breaking News Events". American Behavioral Scientist: 0002764212469367. doi:10.1177/0002764212469367. ISSN 0002-7642.

- ^ Howard, Philip N. (2002-12-01). "Network Ethnography and the Hypermedia Organization: New Media, New Organizations, New Methods". New Media & Society. 4 (4): 550–574. doi:10.1177/146144402321466813. ISSN 1461-4448.

- ^ Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. Vol. 78. pp. 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Social networks and organisations. Sage Publications. 2003.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Analyzing Social Media Networks with NodeXL. Morgan Kaufmann. 2010. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-12-382229-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Liu, Bing (2011). Web Data Mining: Exploring Hyperlinks, Contents, and Usage Data. Springer. p. 271. ISBN 978-3-642-19459-7.

- ^ "Concepts and Measures for Basic Network Analysis". The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis. SAGE. 2011. pp. 364–367. ISBN 978-1-84787-395-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Social Network Analysis for Startups: Finding Connections on the Social Web. O'Reilly. 2011. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4493-1762-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Opsahl, Tore; Agneessens, Filip; Skvoretz, John (2010). "Node centrality in weighted networks: Generalizing degree and shortest paths". Social Networks. 32 (3): 245–251. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2010.03.006.

- ^ "Social Network Analysis". Field Manual 3-24: Counterinsurgency (PDF). Headquarters, Department of the Army. pp. B-11–B-12.

- ^ Web Mining and Social Networking: Techniques and Applications. Springer. 2010. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4419-7734-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Concepts and Measures for Basic Network Analysis". The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis. SAGE. 2011. pp. 346–347. ISBN 978-1-84787-395-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Clique relaxation models in social network analysis". Handbook of Optimization in Complex Networks: Communication and Social Networks. Springer. 2011. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-4614-0856-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Garton, Laura; Haythornthwaite, Caroline; Wellman, Barry (1997-06-01). "Studying Online Social Networks". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 3 (1): 0–0. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00062.x. ISSN 1083-6101.

- ^ Garton, Laura; Haythornthwaite, Caroline; Wellman, Barry (1997-06-01). "Studying Online Social Networks". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 3 (1): 0–0. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00062.x. ISSN 1083-6101.

- ^ Mislove, Alan; Marcon, Massimiliano; Gummadi, Krishna P.; Druschel, Peter; Bhattacharjee, Bobby (2007-01-01). "Measurement and Analysis of Online Social Networks". Proceedings of the 7th ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement. IMC '07. New York, NY, USA: ACM: 29–42. doi:10.1145/1298306.1298311. ISBN 9781595939081.

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "asanet" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "comprehensive" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "development" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "interpreting" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "uci" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "visualizing" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Kadu12" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Podo97" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Flyn10" is not used in the content (see the help page).

External links

editFurther reading

edit- Awesome Network Analysis (200+ links to books, conferences, courses, journals, research groups, software, tutorials and more)

- Introduction to Stochastic Actor-Based Models for Network Dynamics - Snijders et al.

- The International Network for Social Network Analysis (INSNA) – professional society of social network analysts, with more than 1,000 members

- Center for Computational Analysis of Social and Organizational Systems (CASOS) at Carnegie Mellon

- NetLab at the University of Toronto, studies the intersection of social, communication, information and computing networks

- Netwiki (wiki page devoted to social networks; maintained at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

- Program on Networked Governance – Program on Networked Governance, Harvard University

- The International Workshop on Social Network Analysis and Mining (SNA-KDD) - An annual workshop on social network analysis and mining, with participants from computer science, social science, and related disciplines.

- Historical Dynamics in a time of Crisis: Late Byzantium, 1204–1453 (a discussion of social network analysis from the point of view of historical studies)

- Social Network Analysis: A Systematic Approach for Investigating

Organizations

editPeer-reviewed journals

edit- Social Networks

- Network Science

- Journal of Social Structure

- Journal of Complex Networks

- Journal of Mathematical Sociology

- Social Network Analysis and Mining (SNAM)

- "Connections". Toronto: International Network for Social Network Analysis. ISSN 0226-1766.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Textbooks and educational resources

edit- Networks, Crowds, and Markets (2010) by D. Easley & J. Kleinberg

- Introduction to Social Networks Methods (2005) by R. Hanneman & M. Riddle

- Analyzing the Social Web (2013) by J. Golbeck

Data sets

edit- Pajek's list of lists of datasets

- UC Irvine Network Data Repository

- Stanford Large Network Dataset Collection

- M.E.J. Newman datasets

- Pajek datasets

- Gephi datasets

- KONECT - Koblenz network collection

- RSiena datasets