A rock drill is a tool used in mining and civil engineering to drill into rock. Rock drills are used for making holes for placing dynamite or other explosives in rock blasting, and holes for plug and feather quarrying.[1]

While a rock drill may be as simple as a specialized form of chisel, it may also take the form of a powered machine. The mechanism may be worked or powered by hand, by steam, by compressed air (pneumatics), by hydraulics, or by electricity.

Machine rock drills come in two basic forms: those that operate by percussion (using a reciprocating motion), and those that are abrasive (using a rotary motion).[2][3] A smaller, hand-held percussion rock drill is considered a type of jackhammer.

History and types

editThe simplest form of rock drill consists of a long chisel or drill steel that was struck with a sledgehammer.[4] Mark Twain, who worked unsuccessfully as a silver miner in the early 1860s before taking up journalism, described the process: "One of us held the iron drill in its place and another would strike with an eight-pound sledge--it was like driving nails on a large scale. In the course of an hour or two the drill would reach a depth of two or three feet, making a hole a couple of inches in diameter."[5] This hole was then filled with the blasting powder. In "jump-driving", a team of 2-4 men worked a single hole, each taking turns pounding. Around 1900, the average a jump-driver could produce 50 feet (15 m) of hole a day.(Steam Shovel 136)

Powered rock drills eventually replaced the manual use of a chisel to bore holes by the turn of the 20th century. The dramatic differences between the hand steel and power drills was the basis for the legend of American folk hero John Henry, who according to folklore undertook a competition pitting his hand steel against a steam power drill, only to collapse dead when victorious.[6]

The first steam drill was developed in 1813 by Richard Trevithick.[7] Steam drills found greater use in surface quarries than in underground mines, as there they could be much closer to the requisite boilers.(Davies 156)

Length of the reciprocation

hazards of drilling dust; needing to wet it down

In 1867, French civil engineer M. Leschott introduced the diamond drill bit.[8]

Configurations

editIn reciprocating power drills, the drilling cylinder is mounted on a feed-screw, such that as the hole is drilled and the drilling point recedes from the rock face, the drill-bit continues to move into it, while the anchor point (on the tripod or column) remains in place.[9] The drill bit has to be changed out for a longer one every 12 to 30 inches (30 to 76 cm), depending on the length of the feed screw.[10]

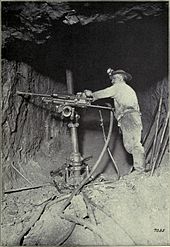

Rock drills may be mounted for anchoring against the rockface in several different ways. For downward vertical drilling, particularly in quarrying, rock drills may be mounted on tripods with attached weights so as to provide sufficient pressure against the surface.[10] (Davies 156) For horizontal drilling, jack mounts or columns locked into the ceiling and floor of the given level in a mine.

A quarry bar consists of a rock drill mounted to a long rod, such that the rock drill may be moved along it. This tool is used in quarrying to produce a straight row of holes, such as for use with the plug and feather to split the stone along the given line.[1]

Hand-held jackhammers

Drill bits

editThe general difficulty in drilling rock is that the rock is often harder than the drill material, tending to quickly wear out any sharpened edges.[11] The differential wear between different bits used to make a single hole could result in an uneven hole in which a blasting charge might not properly fit.[12] This was a potentially dangerous situation with relatively unstable explosives, such as dynamite, if they were forced.[12] To prevent this, a tool was used for measuring the individual bits and the hole.[12]

Making the bits/sharpening them

Rotary rock drills use bits coated in diamond (in the form of bort).[13] The diamonds are set into, and protruding from, the metal portion of the bit such that it is the diamond, rather than the metal, which comes into contact with the rock.[8] As diamond is harder than the rock body, it is the rock which is ground away rather than the bit.

In situations where soil is frozen, jumper drills are heated, and in some situations, mounted with steam tips.(steam shovel 135)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Sullivan Machinery Company (1903). The Excavation of Rock by Machinery. New York: Chasmar-Winchell Press. pp. 39, 41.

- ^ Davies, E. Henry (1902). Machinery for Metalliferous Mines. London: Crosby Lockwood. pp. 151–152.

- ^ Raymond, R.W. (1881). "rock-drill". Glossary of Mining and Metallurgical Terms. Easton, Pa.: American Institute of Mining Engineers.

- ^ Raymond, R.W. (1881). "drill". Glossary of Mining and Metallurgical Terms. Easton, Pa.: American Institute of Mining Engineers.

- ^ Twain, Mark (1891). Roughing It. Hartford, Conn.: American Publishing Company. p. 212.

- ^ Grimes, William. "Taking Swings at a Myth, With John Henry the Man", New York Times, Books section, October 18, 2006.

- ^ Weston, Eustace M. (1910). Rock Drills: Design, Construction, and Use. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. p. 1.

- ^ a b Le Ruey, Edward (1877). Hints on Mining Affairs. London, Ont.: Advertiser Steam Presses. pp. 7–8.

- ^ Kirk, Arthur (1891). The Quarryman and Contractor's Guide. Pittsburgh, PA.: W. J. Golder & Co. pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Cosgrove, John Joseph (1913). Rock Excavating and Blasting. Pittsburgh: National Fire Proofing Company. pp. 35–44.

- ^ André, George Guillaume (1878). Rock Blasting: A Practical Treatise on the Means Employed in Blasting Rocks for Industrial Purposes. London: E. & F. N. Spon.

- ^ a b c Maurice, William (ca. 1910). The Shot-Firer's Guide. London: "The Electrician" Printing and Publishing Company Ltd. pp. 79–80.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Raymond, R.W. (1881). "diamond-drill". Glossary of Mining and Metallurgical Terms. Easton, Pa.: American Institute of Mining Engineers.

- Marsh Jr., Robert (1920). Steam Shovel Mining. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 135 et seq.