Draft:Myxomatosis in North America (California Myxomatosis)

| Submission declined on 15 November 2024 by SafariScribe (talk). I see a great copying from Myxomatosis.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

|  |

Comment: Myxomatosis already exists a 'Good Article'. If there is enough information for a separate sub article on 'California Myxomatosis' fine but it should not just redo Myxomatosis but only focused on North America, it should be written as a sub of the main article focusing on the North American specifics. Large sections of this are just an unattributed copy of Myxomatosis. KylieTastic (talk) 11:35, 28 October 2024 (UTC)

Comment: Myxomatosis already exists a 'Good Article'. If there is enough information for a separate sub article on 'California Myxomatosis' fine but it should not just redo Myxomatosis but only focused on North America, it should be written as a sub of the main article focusing on the North American specifics. Large sections of this are just an unattributed copy of Myxomatosis. KylieTastic (talk) 11:35, 28 October 2024 (UTC)

Sandbox in which Rabbit Vet will be playing... Myxomatosis in North America (Californian Myxomatosis)

| Myxoma virus | |

|---|---|

| |

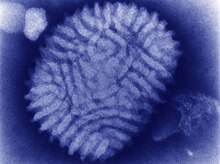

| Myxoma virus (transmission electron microscope) | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Varidnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Bamfordvirae |

| Phylum: | Nucleocytoviricota |

| Class: | Pokkesviricetes |

| Order: | Chitovirales |

| Family: | Poxviridae |

| Genus: | Leporipoxvirus |

| Species: | Myxoma virus

|

Myxomatosis is a disease caused by the myxoma virus, a poxvirus in the genus Leporipoxvirus. The natural host of the myxoma virus in North America is the brush rabbit (Sylvilagus bachmani). This virus causes only mild disease in the brush rabbit, but causes a severe and usually fatal disease in European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), the species of rabbit commonly kept as pets or used as a food source.

Cause

editThe myxoma virus is in the genus Leporipoxvirus (family Poxviridae; subfamily Chordopoxvirinae). Like other poxviruses, myxoma viruses are large DNA viruses with linear double-stranded DNA. Virus replication occurs in the cytoplasm of the cell. In North America the natural host of the virus is the brush rabbit (Sylvilagus bachmani). The myxoma virus causes only a mild disease in brush rabbits, with signs limited to the formation of short-lived skin nodules.[1]

Myxomatosis is the name of the severe and often fatal disease in European rabbits caused by the myxoma virus. Different strains exist which vary in their virulence. The Californian strain, which is endemic to the west coast of the United States and Baja in Mexico, is the most virulent, with reported case fatality rates approaching 100%.[2] The distribution of Myxomatosis in North America is limited to the brush rabbit’s native habitat, which extends from the Columbia River in Oregon to the north, the Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountains to the East, and the tip of the Baja California peninsula to the south.[3] The brush rabbit is the sole carrier of myxoma virus in North American because other native lagomorphs, including cottontail rabbits and hares, are incapable of transmitting the disease.[4][1]

Transmission

editMyxomatosis is transmitted primarily by insects. The myxoma virus does not replicate in these arthropod hosts, but is physically carried by biting arthropods from one rabbit to another. In North America mosquitoes are the primary mode of viral transmission, and multiple species of mosquito can carry the virus.[1][5][6][7] Transmission via the bites of fleas, flies, lice, and mites have also been documented.[8][9] Outbreaks have a seasonal nature and are most likely to occur between August and November, but cases can occur year round.[10] Seasonality is driven by the availability of arthropod vectors and the proximity of infected wild rabbits.[11]

The myxoma virus can also be transmitted by direct contact. Infected rabbits shed the virus in ocular and nasal secretions and from areas of eroded skin. The virus may also be present in semen and genital secretions. Poxviruses are fairly stable in the environment and can be spread by contaminated objects such as water bottles, feeders, caging, or people's hands.[11]

Clinical presentation

editThe clinical signs of myxomatosis depend on the strain of virus, the route of inoculation, and the immune status of the host. Cases of myxomatosis in northern California, southern California, Oregon, and Mexico are caused by different strains of myxoma virus, and clinical signs vary.

California

editA 1931 paper reported twelve cases of myxomatosis from Santa Barbara, Ventura, and San Diego counties of California. Affected rabbits developed mucopurulent conjunctivitis and swelling of the nose, lips, ears, and external genitalia. Rabbits that survived for over a week developed cutaneous nodules on the face.[12]

A 2024 study found that myxomatosis caused by the MSW strain (California/San Francisco 1950) of the myxoma virus occurs regularly in the greater San Jose and Santa Cruz regions of California. Common physical examination findings included swollen eyelids, swollen genitals, fever, and lethargy. Swollen lips and ears and subcutaneous edema also occurred in some rabbits. Domesticated rabbits that spent time outdoors were at greater risk of acquiring the disease, and most of the cases occurred between August and October. It was postulated that that the number of cases brought to veterinarians underestimated the total number of cases, as sudden death was sometimes the first sign noted.[10]

Oregon

editA 1977 report from western Oregon described several cases of myxomatosis. The most common clinical signs observed were inflammation and swelling of the eyelids, conjunctiva, and anogenital region. Lethargy, fever, and anorexia were also observed. A single rabbit with confirmed myxomatosis eventually recovered.[13]

A 2003 report of a myxomatosis outbreak in western Oregon reported sudden death as a common finding. Also noted were lethargy, swollen eyelids, and swollen genital regions.[14]

Baja California

editA 2000 report from the Baja Peninsula in Mexico described two outbreaks of myxomatosis in 1993. Affected domestic rabbits developed skin nodules and respiratory symptoms.[15]

Diagnosis

editBecause the clinical signs of myxomatosis are distinctive and nearly pathognomonic, initial diagnosis is largely based on physical exam findings.[16][17][18] If a rabbit dies without exhibiting the classic signs of myxomatosis, or if further confirmation is desired, a number of laboratory tests are available.

Tissues from rabbits suffering from California myxomatosis show a number of typical changes on histopathology. Affected skin and mucous membranes typically show undifferentiated mesenchymal cells within a matrix of mucin, inflammatory cells, edema, and intracytoplasmic viral inclusion bodies. Spleen and lymph nodes are often affected by lymphoid depletion. Necrotizing appendicitis and secondary infections with gram-negative bacteria are also common.[10][13][14]

The development of molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and real-time polymerase chain reaction assays has created faster and more accurate methods of myxoma virus identification.[19] PCR can be used on swabs, fresh tissue samples, and on paraffin-embedded tissue samples to confirm the presence of the myxoma virus and as well as to identify the viral strain.[20]

Other Testing

editOther means of diagnosing myxomatosis include immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and virus isolation. Immunohistochemistry can demonstrate the presence of myxoma virus particles in different cells and tissues of the body.[10][14] Negative-stain electron microscopic examination can be used to identify the presence of a poxvirus, although it does not allow specific verification of virus species or variants.[19] Virus isolation remains the "gold standard" against which other methods of virus detection are compared. Theoretically at least, a single viable virus present in a specimen can be grown in cultured cells, thus expanding it to produce enough material to permit further detailed characterization.[21]

Treatment

editAt present, no specific treatment exists for myxomatosis. Given that the mortality rate of North American strains of myxomatosis nears 100%, euthanasia is often recommended.[10] If treatment is attempted then careful monitoring is necessary to avoid prolonging suffering. Cessation of food and water intake, ongoing severe weight loss, or rectal temperatures below 37 °C (98.6 °F) are reasons to consider euthanasia.[11][22]

Prevention

editVaccination

editVaccines against myxomatosis are available in some countries. All are modified live vaccines based either on attenuated myxoma virus strains or on the closely related Shope fibroma virus, which provides cross-immunity. It is recommended that all rabbits in areas of the world where myxomatosis is endemic be routinely vaccinated, even if kept indoors, because of the ability of the virus to be carried inside by vectors or fomites. In group situations where rabbits are not routinely vaccinated, vaccination in the face of an outbreak is beneficial in limiting morbidity and mortality.[23] The vaccine does not provide 100% protection,[11] so it is still important to prevent contact with wild rabbits and insect vectors. Myxomatosis vaccines must be boostered regularly to remain effective, and annual vaccinations are usually recommended.[23]

Unfortunately there is no commercially available vaccine against myxomatosis in Mexico or the United States.

Other preventive measures

editIn locations where myxomatosis is endemic but no vaccine is available, preventing exposure to the myxoma virus is of vital importance. The risk of a pet contracting myxomatosis can be reduced by preventing contact with wild rabbits, and by keeping rabbits indoors (preferred) or behind screens to prevent mosquito exposure. Using rabbit-safe medications to treat and prevent fleas, lice, and mites is also warranted. New rabbits that could have been exposed to the virus should be quarantined for 14 days before being introduced to current pets.

Any rabbit suspected of having myxomatosis should be immediately isolated, and all rabbits in the area moved indoors. To prevent the virus from spreading further any cages and cage furnishings that have come into contact with infected rabbits should be disinfected, and owners should disinfect their hands between rabbits. Poxviruses are stable in the environment and can be spread by fomites but are highly sensitive to chemical disinfection; bleach, ammonia, and alcohol can all be used to deactivate myxoma virus.[24]

Reporting

editMyxomatosis is a reportable disease in California, the United States, and in Mexico.[25][26][27] Veterinarians and pet owners who see this disease are encouraged to report all cases to the relevant agencies. Without accurate data on myxomatosis in North America, vaccine manufacturers will underestimate the need for a vaccine and be reluctant to produce one.

References

edit- ^ a b c Grodhaus, G; Regnery, DC; Marshall, ID (1963). "Studies in the epidemiology of myxomatosis in California. II. The experimental transmission of myxomatosis in brush rabbits (Sylvilagus bachmani) by several species of mosquitoes". Am J Hyg. 77: 205–212. PMID 13950625.

- ^ Silvers, L; Inglis, B; Labudovic, A; Janssens, PA; van Leeuwen, BH; Kerr, PJ (2006). "Virulence and pathogenesis of the MSW and MSD strains of Californian myxoma virus in European rabbits with genetic resistance to myxomatosis compared to rabbits with no genetic resistance". Virology. 348 (1): 72–83. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.007. PMID 16442580.

- ^ Regnery, DC; Marshall, ID (1971). "Studies in the epidemiology of myxomatosis in California". American Journal of Epidemiology. 94 (5): 508–513. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121348. PMID 5166039.

- ^ Silvers, L; Barnard, D; Knowlton, F; Inglis, B; Labudovic, A; Holland, MK; Janssens, PA; van Leeuwen, BH; Kerr, PJ (2010). "Host-specificity of myxoma virus: Pathogenesis of South American and North American strains of myxoma virus in two North American lagomorph species". Veterinary Microbiology. 141 (3–4): 289–300. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.09.031. PMID 19836172.

- ^ Marshall, ID; Regnery, DC; Grodhaus, G (1963). "Studies in the epidemiology of myxomatosis in California I. Observations on two outbreaks of myxomatosis in coastal California and the recovery of myxoma virus from a brush rabbit (Sylvilagus bachmani)". American Journal of Epidemiology. 77 (2): 195–204. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120310.

- ^ Regnery, DC; Marshall, ID (1971). "Studies in the epidemiology of myxomatosis in California. IV. The susceptibility of six leporid species to Californian myxoma virus and the relative infectivity of their tumors for mosquitoes". American Journal of Epidemiology. 94 (5): 508–513. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121348. PMID 5166039.

- ^ Regnery, DC; Miller, JH (1972). "A myxoma virus epizootic in a brush rabbit population". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 8 (4): 327–331. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-8.4.327. PMID 4634525.

- ^ Bertagnoli, S; Marchandeau, S (2015). "Myxomatosis". Revue Scientifique et Technique de l'OIE. 34 (2): 539–556. doi:10.20506/rst.34.2.2378. PMID 26601455.

- ^ Ross, J; Tittensor, AM; Fox, AP; Sanders, MF (1989). "Myxomatosis in farmland rabbit populations in England and Wales". Epidemiology and Infection. 103 (2): 333–357. doi:10.1017/s0950268800030703. PMC 2249516. PMID 2806418.

- ^ a b c d e Stern, HS; Biswell, E; Kiupel, M; Ossiboff, RJ; Brust, K (2024). "Epidemiologic, clinicopathologic, and diagnostic findings in pet rabbits with myxomatosis caused by the California MSW strain of myxoma virus: 11 cases (2022–2023)". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 262 (9): 1–11. doi:10.2460/javma.24.02.0139. PMID 38788762.

- ^ a b c d Kerr, P (2013). "Viral Infections of Rabbits". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 16 (2): 437–468. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2013.02.002. PMC 7110462. PMID 23642871.

- ^ Kessel, JF; Prouty, CC; Meyer, JW (1931). "Occurrence of infectious myxomatosis in southern California". Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 28 (4): 413-414. doi:10.3181/00379727-28-5342.

- ^ a b Patton, NM; Holmes, HT (1977). "Myxomatosis in domestic rabbits in Oregon". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 171 (6): 560–562. PMID 914688.

- ^ a b c Löhr, CV; Kiupel, M; Bildfell, RJ (2005). "Outbreak of myxomatosis in domestic rabbits in Oregon: pathology and detection of viral DNA and protein". Veterinary Pathology. 42 (5): 680–729. doi:10.1177/030098580504200501.

- ^ Licón Luna, RM (2000). "First report of myxomatosis in Mexico". J Wildl Dis. 36 (3): 580–583. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-36.3.580. PMID 10941750.

- ^ Kerr P (2013). "Myxomatosis". In Mayer, J; Donnelly, TM (eds.). Clinical Veterinary Advisor: Birds and Exotic Pets. Elsevier Saunders. pp. 398–401.

- ^ Smith MV (2023). "Urogenital diseases". In Smith, MV (ed.). Textbook of Rabbit Medicine (3rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 314–331.

- ^ Girolamo ND; Selleri P (2021). "Disorders of the urinary and reproductive systems". In Quesenberry, KE; Orcutt, CJ; Mans, C; Carpenter, JW (eds.). Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents (4th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 201–219.

- ^ a b MacLachlan, J (2017). Fenner's Veterinary Virology, 5th Edition. Elsevier. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-12-800946-8.

- ^ Albini, S; Sigrist, B; Güttinger, R; Schelling, C; Hoop, RK; Vögtlin, A (2012). "Development and validation of a Myxoma virus real-time polymerase chain reaction assay". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 24 (1): 135–137. doi:10.1177/1040638711425946. PMID 22362943.

- ^ MacLachlan, J (2017). Fenner's Veterinary Virology, 5th Edition. Elsevier. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-12-800946-8.

- ^ Wolfe, AM; Rahman, M; McFadden, DG; Bartee, EC (2018). "Refinement and successful implementation of a scoring system for myxomatosis in a susceptible rabbit ( Oryctolagus cuniculus ) Model". Comparative Medicine. 68 (4): 280–285. doi:10.30802/AALAS-CM-18-000024. PMC 6103426. PMID 30017020.

- ^ a b Meredith, AL (2013). "Viral skin diseases of the rabbit". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 16 (3): 705–714. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2013.05.010. PMID 24018033.

- ^ Delhon, Gustavo (2022). "Poxviridae". Veterinary Microbiology: 522–532. doi:10.1002/9781119650836.ch53. ISBN 978-1-119-65075-1.

- ^ "List of Reportable Conditions for Animals and Animal Products" (PDF). Animal Health Branch. California Department of Food and Agriculture. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ "Reportable Diseases, Infections, and Infestations List" (PDF). National Animal Health Reporting System. USDA Animal Plant and Health Inspection Service. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ "Myxomatosis" (PDF). General Directorate of Animal Health, Mexico. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

Further reading

edit- Fenner, Frank; Ratcliffe, F.N. (1965). Myxomatosis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521049917.

External links

edit