| Eanna | |

|---|---|

𒂍𒀭𒈾 | |

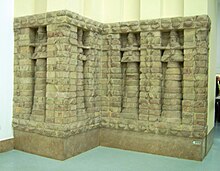

Part of the front of Inanna's temple from Uruk | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sumerian religion |

| Deity | Inanna |

| Location | |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°19′27″N 45°38′14″E / 31.32417°N 45.63722°E |

E-anna (Sumerian: 𒂍𒀭𒈾 É2-AN.NA, house of heavens) was an ancient Sumerian temple in Uruk. Considered "the residence of Inanna" and Anu, it is mentioned several times in the Epic of Gilgamesh, and elsewhere. The evolution of the gods to whom the temple was dedicated is the subject of scholarly study. According to the Sumerian King List (SKL), Uruk was founded by the king Enmerkar. Though the SKL mentions a king of Eanna before him, the epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta relates that Enmerkar constructed the House of Heaven for the goddess Inanna in the Eanna District of Uruk. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh builds the city wall around Uruk and is king of the city.

Uruk went through several phases of growth, from the Early Uruk period (4000–3500 BC) to the Late Uruk period (3500–3100 BC). The city was formed when two smaller Ubaid settlements merged. The temple complexes at their cores became the Eanna District and the Anu District dedicated to Inanna and Anu, respectively. The Anu District was originally called 'Kullaba' (Kulab or Unug-Kulaba) prior to merging with the Eanna District. Kullaba dates to the Eridu period when it was one of the oldest and most important cities of Sumer. There are different interpretations about the purposes of the temples. However, it is generally believed they were a unifying feature of the city. It also seems clear that temples served both an important religious function and state function. The surviving temple archive of the Neo-Babylonian period documents the social function of the temple as a redistribution center.

The Eanna District was composed of several buildings with spaces for workshops, and it was walled off from the city. By contrast, the Anu District was built on a terrace with a temple at the top. It is clear Eanna was dedicated to Inanna from the earliest Uruk period throughout the history of the city. The rest of the city was composed of typical courtyard houses, grouped by profession of the occupants, in districts around Eanna and Anu. Uruk was extremely well penetrated by a canal system that has been described as, "Venice in the desert." This canal system flowed throughout the city connecting it with the maritime trade on the ancient Euphrates River as well as the surrounding agricultural belt.

The Eanna district is historically significant as both writing and monumental public architecture emerged here during Uruk periods VI-IV. The combination of these two developments places Eanna as arguably the first true city and civilization in human history. Eanna during period IVa contains the earliest examples of cuneiform writing and possibly the earliest writing in history. Although some of these cuneiform tablets have been deciphered, difficulty with site excavations has obscured the purpose and sometimes even the structure of many buildings.

Uruk period (c. 4000 – c. 3100 BCE)

editMiddle Uruk phase (c. 3800 – c. 3400 BCE)

editUruk level VI (c. 3500 BCE)

editThe first building of Eanna, Stone-Cone Temple (Mosaic Temple), was built in period VI over a preexisting Ubaid temple and is enclosed by a limestone wall with an elaborate system of buttresses. The Stone-Cone Temple, named for the mosaic of colored stone cones driven into the adobe brick façade, may be the earliest water cult in Mesopotamia. It was ritually demolished in Uruk IVb period and its contents interred in the Riemchen Building.

Late Uruk phase (c. 3400 – c. 3100 BCE)

editUruk level V (c. 3500 – c. 3350 BCE)

editIn the following period, Uruk V, about 100 m east of the Stone-Cone Temple the Limestone Temple was built on a 2 m high rammed-earth podium over a pre-existing Ubaid temple, which like the Stone-Cone Temple represents a continuation of Ubaid culture. However, the Limestone Temple was unprecedented for its size and use of stone, a clear departure from traditional Ubaid architecture. The stone was quarried from an outcrop at Umayyad about 60 km east of Uruk. It is unclear if the entire temple or just the foundation was built of this limestone. The Limestone temple is probably the first Inanna temple, but it is impossible to know with certainty. Like the Stone-Cone temple the Limestone temple was also covered in cone mosaics. Both of these temples were rectangles with their corners aligned to the cardinal directions, a central hall flanked along the long axis flanked by two smaller halls, and buttressed façades; the prototype of all future Mesopotamian temple architectural typology.

Uruk level IV (c. 3350 – c. 3100 BCE)

editBetween these two monumental structures a complex of buildings (called A-C, E-K, Riemchen, Cone-Mosaic), courts, and walls was built during Eanna IVb. These buildings were built during a time of great expansion in Uruk as the city grew to 250 hectares and established long-distance trade, and are a continuation of architecture from the previous period.

During Eanna IVa, the Limestone Temple was demolished and the Red Temple built on its foundations. The accumulated debris of the Uruk IVb buildings were formed into a terrace, the L-Shaped Terrace, on which Buildings C, D, M, Great Hall, and Pillar Hall were built. Building E was initially thought to be a palace, but later proven to be a communal building. Also in period IV, the Great Court, a sunken courtyard surrounded by two tiers of benches covered in cone mosaic, was built. A small aqueduct drains into the Great Courtyard, which may have irrigated a garden at one time. The impressive buildings of this period were built as Uruk reached its zenith and expanded to 600 hectares. All the buildings of Eanna IVa were destroyed sometime in Uruk III, for unclear reasons.

The Riemchen Building, named for the 16×16 cm brick shape called Riemchen by the Germans, is a memorial with a ritual fire kept burning in the center for the Stone-Cone Temple after it was destroyed. For this reason, Uruk IV period represents a reorientation of belief and culture. The facade of this memorial may have been covered in geometric and figural murals. The Riemchen bricks first used in this temple were used to construct all buildings of Uruk IV period Eanna. The use of colored cones as a façade treatment was greatly developed as well, perhaps used to greatest effect in the Cone-Mosaic Temple. Composed of three parts: Temple N, the Round Pillar Hall, and the Cone-Mosaic Courtyard, this temple was the most monumental structure of Eanna at the time. They were all ritually destroyed and the entire Eanna district was rebuilt in period IVa at an even grander scale.

Jemdet Nasr period (c. 3100 – c. 2900 BCE)

editFinal Uruk phase (c. 3100 – c. 2900 BCE)

editUruk level III (c. 3100 – c. 2900 BCE)

editThe architecture of Eanna in period III was very different from what had preceded it. The complex of monumental temples was replaced with baths around the Great Courtyard and the labyrinthine Rammed-Earth Building. This period corresponds to Early Dynastic Sumer c. 2900 BC, a time of great social upheaval when the dominance of Uruk was eclipsed by competing city-states. The fortress-like architecture of this time is a reflection of that turmoil. The temple of Inanna continued functioning during this time in a new form and under a new name, 'The House of Inanna in Uruk' (Sumerian: e2-dinanna unuki-ga). The location of this structure is currently unknown.

Akkadian period (c. 2334 – c. 2154 BCE)

editAlthough it had been a thriving city in Early Dynastic Sumer, especially Early Dynastic II, Uruk was ultimately annexed by the Akkadian Empire and went into decline.

Ur III period (c. 2112 – c. 2004 BCE)

editLater, in the Neo-Sumerian period, Uruk enjoyed revival as a major economic and cultural center under the sovereignty of Ur. The Eanna District was restored as part of an ambitious building program, which included a new temple for Inanna. This temple included a ziggurat, the 'House of the Universe' (Cuneiform: E2.SAR.A) to the northeast of the Uruk period Eanna ruins.

See also

editReferences

editNotes

editCitations

editSources

editBibliography

editJournals

editExternal links

editGeography

editLanguage

edit- Black, Jeremy Allen; Baines, John Robert; Dahl, Jacob L.; Van De Mieroop, Marc. Cunningham, Graham; Ebeling, Jarle; Flückiger-Hawker, Esther; Robson, Eleanor; Taylor, Jon; Zólyomi, Gábor (eds.). "ETCSL: The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Faculty of Oriental Studies (revised ed.). United Kingdom. Retrieved 2022-09-23.

The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL), a project of the University of Oxford, comprises a selection of nearly 400 literary compositions recorded on sources which come from ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and date to the late third and early second millennia BCE.

- Renn, Jürgen; Dahl, Jacob L.; Lafont, Bertrand; Pagé-Perron, Émilie (2022) [1998]. "CDLI: Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative" (published 1998–2022). Retrieved 2022-09-23.

Images presented online by the research project Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI) are for the non-commercial use of students, scholars, and the public. Support for the project has been generously provided by the Mellon Foundation, the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the Institute of Museum and Library Services (ILMS), and by the Max Planck Society (MPS), Oxford and University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA); network services are from UCLA's Center for Digital Humanities.

- Sjöberg, Åke Waldemar; Leichty, Erle; Tinney, Steve (2022) [2003]. "PSD: The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary" (published 2003–2022). Retrieved 2022-09-23.

The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary Project (PSD) is carried out in the Babylonian Section of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology. It is funded by the NEH and private contributions. [They] work with several other projects in the development of tools and corpora. [Two] of these have useful websites: the CDLI and the ETCSL.