| Diapsid reptiles | |

|---|---|

| |

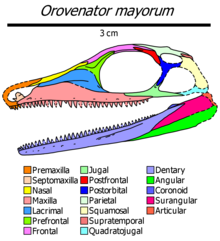

| Skull of Orovenator, one of the earliest known diapsids | |

| |

| Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Romeriida |

| Clade: | Diapsida Osborn, 1903 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Diapsida ("two arches") is a clade of sauropsids (reptiles in the wide sense), distinguished by the presence of two holes, known as temporal fenestrae, in each side of their skulls. Modern reptiles and birds belong to the diapsid subclade Sauria.

The earliest tetrapods with two pairs of temporal fenestrae were the araeoscelidians, which first appeared about three hundred million years ago during the Late Carboniferous.[1] Araeoscelidians are often regarded as the most basal (early-diverging) diapsid reptiles, but have been found by some phylogenetic analyses to instead be stem-amniotes and therefore not closely related to other diapsids.[2] Non-araeoscelidian diapsids are often placed in the subclade Neodiapsida; the earliest known members of this group are Orovenator and Maiothisavros from the Early Permian, around 290 million years ago.[3][4] Two other groups, Parareptilia and Varanopidae, have sometimes been recovered as basal diapsids, but are usually considered to be non-diapsid reptiles and synapsids (stem-mammals) respectively.[5]

Early diapsids were ancestrally lizard-like, but non-saurian diapsids include semiaquatic taxa (like Claudiosaurus and some tangasaurids),[6] the gliding lizard-like Weigeltisauridae,[7] and possibly the Triassic chameleon-like drepanosaurs.[8] The position of the highly derived Mesozoic marine reptile groups Thalattosauria, Ichthyosauromorpha and Sauropterygia within Diapsida is uncertain, and they may lie within Sauria.[9]

Modern diapsids are extremely diverse, and include birds and all modern reptile groups, including turtles, which were historically thought to lie outside the group.[10] Although some diapsids have lost either one hole (lizards), or both holes (snakes and turtles), or have a heavily restructured skull (modern birds), they are still classified as diapsids based on their ancestry. At least 17,084 species of diapsid animals are extant: 9,159 birds,[11] and 7,925 snakes, lizards, tuatara, turtles, and crocodiles.[12]

Characteristics

editThe name Diapsida means "two arches", and diapsids are traditionally classified based on their two ancestral skull openings (temporal fenestrae) posteriorly above and below the eye. This arrangement allows for the attachment of larger, stronger jaw muscles, and enables the jaw to open more widely. A more obscure ancestral characteristic is a relatively long lower arm bone (the radius) compared to the upper arm bone (humerus).

Classification

editDiapsids were originally classified as one of four subclasses of the class Reptilia, all of which were based on the number and arrangement of openings in the skull. The other three subclasses were Synapsida (one opening low on the skull, for the "mammal-like reptiles"), Anapsida (no skull opening, including turtles and their relatives), and Euryapsida (one opening high on the skull, including many prehistoric marine reptiles). With the advent of phylogenetic nomenclature, this system of classification was heavily modified. Today, the synapsids are often not considered true reptiles, while Euryapsida were found to be an unnatural assemblage of diapsids that had lost one of their skull openings. Genetic studies and the discovery of the Triassic Pappochelys have shown that this is also the case in turtles, which are actually heavily modified diapsids. In phylogenetic systems, birds (descendants of traditional diapsid reptiles) are also considered to be members of this group.

Some modern studies of reptile relationships have preferred to use the name "diapsid" to refer to the crown group of all modern diapsid reptiles but not their extinct relatives. However, many researchers have also favored a more traditional definition that includes the prehistoric araeoscelidians. In 1991, Michel Laurin gave phylogenetic definitions to Diapsida and Neodiapsida. Diapsida was defined as "the most recent common ancestor of araeoscelidians, lepidosaurs, and archosaurs, and all its descendants".[13] Neodiapsida was defined as the branch-based clade containing all animals more closely related to "Younginiformes" (later, more specifically, emended to Youngina capensis) than to Petrolacosaurus.[14]

A cladistic analysis by Laurin and Piñeiro (2017) recovers Parareptilia as part of Diapsida, with pareiasaurs, turtles, millerettids, and procolophinoids recovered as more derived than the basal diapsid Younginia. However, this excludes mesosaurs, which were found to be basal among the sauropsids.[15] A 2020 study by David P. Ford and Roger B. J. Benson also recovered Parareptilia as deeply nested within Diapsida as the sister group to Neodiapsida.[5]

Relationships

editCladogram after Bickelmann et al., 2009[16] and Reisz et al., 2011:[17]

The cladogram below is based on the 2017 study by Pritchard and Nesbitt.[18]

| Neodiapsida | |

The following cladogram was found by Simões et al. (2022):[2]

| Neoreptilia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Diapsida". ucmp.berkeley.edu.

- ^ a b Simões, Tiago R.; Kammerer, Christian F.; Caldwell, Michael W.; Pierce, Stephanie E. (2022-08-19). "Successive climate crises in the deep past drove the early evolution and radiation of reptiles". Science Advances. 8 (33): eabq1898. Bibcode:2022SciA....8.1898S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abq1898. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 9390993. PMID 35984885.

- ^ Ford, David P.; Benson, Roger B. J. (May 2019). Mannion, Philip (ed.). "A redescription of Orovenator mayorum (Sauropsida, Diapsida) using high‐resolution μ CT , and the consequences for early amniote phylogeny". Papers in Palaeontology. 5 (2): 197–239. doi:10.1002/spp2.1236. ISSN 2056-2802. S2CID 92485505.

- ^ Mooney, Ethan D.; Maho, Tea; Bevitt, Joseph J.; Reisz, Robert R. (2022-11-30). Liu, Jun (ed.). "An intriguing new diapsid reptile with evidence of mandibulo-dental pathology from the early Permian of Oklahoma revealed by neutron tomography". PLOS ONE. 17 (11): e0276772. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0276772. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9710763. PMID 36449456.

- ^ a b Ford DP, Benson RB (2020). "The phylogeny of early amniotes and the affinities of Parareptilia and Varanopidae". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (1): 57–65. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-1047-3. PMID 31900445. S2CID 209673326.

- ^ Nuñez Demarco, Pablo; Meneghel, Melitta; Laurin, Michel; Piñeiro, Graciela (2018-07-27). "Was Mesosaurus a Fully Aquatic Reptile?". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 6: 109. doi:10.3389/fevo.2018.00109. hdl:20.500.12008/30631. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ Pritchard, Adam C.; Sues, Hans-Dieter; Scott, Diane; Reisz, Robert R. (2021-05-20). "Osteology, relationships and functional morphology of Weigeltisaurus jaekeli (Diapsida, Weigeltisauridae) based on a complete skeleton from the Upper Permian Kupferschiefer of Germany". PeerJ. 9: e11413. doi:10.7717/peerj.11413. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 8141288. PMID 34055483.

- ^ Pritchard, Adam C.; Nesbitt, Sterling J. (October 2017). "A bird-like skull in a Triassic diapsid reptile increases heterogeneity of the morphological and phylogenetic radiation of Diapsida". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (10): 170499. Bibcode:2017RSOS....470499P. doi:10.1098/rsos.170499. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 5666248. PMID 29134065.

- ^ Simões, Tiago R.; Kammerer, Christian F.; Caldwell, Michael W.; Pierce, Stephanie E. (2022-08-19). "Successive climate crises in the deep past drove the early evolution and radiation of reptiles". Science Advances. 8 (33): eabq1898. Bibcode:2022SciA....8.1898S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abq1898. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 9390993. PMID 35984885.

- ^ Schoch, Rainer R.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (2016). "The diapsid origin of turtles". Zoology. 119 (3): 159–161. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2016.01.004. PMID 26934902.

- ^ Barrowclough, George F.; Cracraft, Joel; Klicka, John; Zink, Robert M. (23 November 2016). "How Many Kinds of Birds Are There and Why Does It Matter?". PLOS ONE. 11 (11): e0166307. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1166307B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0166307. PMC 5120813. PMID 27880775.

- ^ Reeder, Tod W.; Townsend, Ted M.; Mulcahy, Daniel G.; Noonan, Brice P.; Wood, Perry L.; Sites, Jack W.; Wiens, John J. (2015). "Integrated Analyses Resolve Conflicts over Squamate Reptile Phylogeny and Reveal Unexpected Placements for Fossil Taxa". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0118199. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1018199R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118199. PMC 4372529. PMID 25803280.

- ^ Benton, M. J., Donoghue, P. C., Asher, R. J., Friedman, M., Near, T. J., & Vinther, J. (2015). "Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history." Palaeontologia Electronica, 18.1.1FC; 1-106; palaeo-electronica.org/content/fc-1

- ^ Reisz, Robert R.; Modesto, Sean P.; Scott, Diane M. (22 December 2011). "A new Early Permian reptile and its significance in early diapsid evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1725): 3731–3737. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0439. PMC 3203498. PMID 21525061.

- ^ Laurin, Michel; Piñeiro, Graciela H. (2017). "A Reassessment of the Taxonomic Position of Mesosaurs, and a Surprising Phylogeny of Early Amniotes" (PDF). Frontiers in Earth Science. 5: 88. Bibcode:2017FrEaS...5...88L. doi:10.3389/feart.2017.00088. S2CID 32426159.

- ^ Constanze Bickelmann, Johannes Müller and Robert R. Reisz (2009). "The enigmatic diapsid Acerosodontosaurus piveteaui (Reptilia: Neodiapsida) from the Upper Permian of Madagascar and the paraphyly of younginiform reptiles". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 49 (9): 651–661. Bibcode:2009CaJES..46..651S. doi:10.1139/E09-038.

- ^ Robert R. Reisz, Sean P. Modesto and Diane M. Scott (2011). "A new Early Permian reptile and its significance in early diapsid evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 278 (1725): 3731–7. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0439. PMC 3203498. PMID 21525061.

- ^ Pritchard, Adam C.; Nesbitt, Sterling J. (2017-10-11). "A bird-like skull in a Triassic diapsid reptile increases heterogeneity of the morphological and phylogenetic radiation of Diapsida". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (10): 170499. Bibcode:2017RSOS....470499P. doi:10.1098/rsos.170499. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 5666248. PMID 29134065.

External links

edit- Data related to Trilletrollet/sandbox at Wikispecies

Category:Reptile taxonomy Category:Cisuralian first appearances Category:Extant Permian first appearances Category:Taxa named by Henry Fairfield Osborn