| Sandbox1 | Sandbox2 | Sandbox3 | Sandbox4 | Sandbox5 | Sandbox6 | Sandbox7 | Sandbox8 | Sandbox9 |

| Please note: The contents of this page are a work in progress. When the page is complete, the changes will be made to the target page. To make comments, suggestions, or contributions to the re-write, please drop me a note on my talk page. |

| Aye-aye[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| |

| An aye-aye eating banana flowers | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Family: | Daubentoniidae Gray, 1863 |

| Genus: | Daubentonia É. Geoffroy, 1795 |

| Species: | D. madagascariensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Daubentonia madagascariensis (Gmelin, 1788)

| |

| |

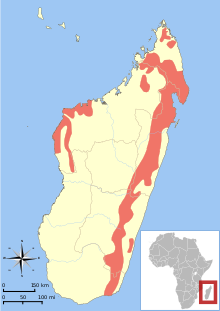

| Aye-aye range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Family:

Genus:

Species:

| |

The aye-aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis) is... [4] [5]

- Etymology

- Evolutionary history

- Anatomy and physiology

- Behavior

- Diet

- Foraging

- Social systems

- Communication

- Distribution and habitat

- Conservation

- Superstition

Etymology

editThe aye-aye's binomial name, Daubentonia madagascariensis, honors the French naturalist Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton and the island on which it is found, Madagascar. Among some Malagasy, the aye-aye is imitatively called "hay-hay"[6] for a vocalization it is claimed to make. It is supposedly from the European acceptance of this name that its common name was derived.[7] However, the aye-aye makes no such vocalization. The name was also hypothesized to be of European origin, with a European observer overhearing an exclamation of fear and surprise ("aiee!-aiee!") by Malagasy who encountered it. However, the name exists in remote villages, so it is unlikely to be of European origins. Another hypothesis is that it derives from "heh heh," which is Malagasy for, "I don't know." If correct, then the name might have originated from Malagasy people saying "heh heh" to Europeans to avoid saying the name of a feared, magical animal.[8]

Evolutionary history and taxonomy

editDue to its derived morphological features, the classification of the aye-aye has been debated since its discovery. The possession of continually growing incisors (front teeth) parallels those of rodents, leading early naturalists to mistakenly classify the aye-aye within mammalian order Rodentia.[9]

The aye-aye's classification with the order Primates has been just as uncertain. It has been considered a highly derived member of the Indridae family, a basal branch of the strepsirrhine suborder, and of indeterminate relation to all living primates.[10] In 1931, Anthony and Coupin classified the aye-aye under infraorder Chiromyiformes, a sister group to the other strepsirrhines. Colin Groves upheld this classification in 2005 because he was not entirely convinced the aye-aye formed a clade with the rest of the Malagasy lemurs,[1] despite molecular tests that had shown Daubentoniidae was basal to all Lemuriformes,[10] deriving from the same lemur ancestor that rafted to Madagascar during the Paleocene or Eocene. In 2008, Russell Mittermeier, Colin Groves, and others ignored addressing higher-level taxonomy by defining lemurs as monophyletic and containing five living families, including Daubentoniidae.[2]

Further evidence indicating that the aye-aye belongs in the superfamily Lemuroidea can be inferred from the presence of a petrosal bullae encasing the ossicles of the ear. However, interestingly, the bones themselves may have some resemblance to those of rodents.[9]

Anatomy and physiology

edit...

Behavior

edit...

Diet

editThe aye-aye commonly eats animal matter, nuts, insect larvae, fruits, nectar, seeds, and fungi, classifying it as an omnivore. Aye-ayes are particularly fond of cerambycid beetles. It picks fruit off trees as it moves through the canopy, often barely stopping to do so. An aye-aye not in its natural habitat will often steal coconuts, mangoes, sugar cane, lychees and eggs from villages and plantations. Aye-ayes tap on the trunks and branches of the trees they visit up to eight times per second, and listen to the echo produced to find hollow chambers inside. Once a chamber is found, they chew a hole into the wood and get grubs out of that hole with their narrow and bony middle fingers.[citation needed]

Foraging

editThe aye-aye begins foraging anywhere between 30 minutes before and three hours after sunset. Up to 80% of the night is spent foraging in the canopy, separated by occasional rest periods. It climbs trees by making successive vertical leaps, much like a squirrel. Horizontal movement is more difficult, but the aye-aye rarely descends to jump to another tree, and can often cross up to 4 km (2.5 mi) a night.[citation needed]

Though foraging is mostly solitary, they will occasionally forage in groups. Individual movements within the group are coordinated using both sound (vocalisations) and scent signals.[citation needed]

Social systems

editThe aye-aye is classically considered 'solitary' as they have not been observed to groom each other.[citation needed] However, recent research suggests it is more social than once thought. It usually sticks to foraging in its own personal home range, or territory. The home ranges of males often overlap, and the males can be very social with each other. Female home ranges never overlap, though a male's home range often overlaps that of several females. The male aye-ayes live in large areas up to 80 acres (320,000 m2), while females have smaller living spaces that goes up to 20 acres (81,000 m2). Regular scent marking with their cheeks and neck is how aye-ayes let others know of their presence and repel intruders from their territory.[11] Like many other prosimians, the female aye-aye is dominant to the male. They are not monogamous by any means, and often compete with each other for mates. Males are very aggressive in this regard, and sometimes even pull other males off a female during mating. Outside of mating, males and females interact only occasionally, usually while foraging.[citation needed]

Communication

edit...

Distribution and habitat

editThe aye-aye lives primarily on the east coast of Madagascar. Its natural habitat is rainforest or deciduous forest, but many live in cultivated areas due to deforesting. Rainforest aye-ayes, the most common, dwell in canopy areas, and are usually sighted upwards of 700 meters altitude. They sleep during the day in nests built in the forks of trees.[citation needed]

Conservation

editThe aye-aye was thought to be extinct in 1933, but was rediscovered in 1957. Nine individuals were transported to Nosy Mangabe, an island near Maroantsetra off eastern Madagascar, in 1966.[12] Recent research shows the aye-aye is more widespread than was previously thought, but is still categorized as Near Threatened.[3]

As many as 50 aye-ayes can be found in zoological facilities worldwide.[13]

Superstition

editThe aye-aye is a near threatened species not only because its habitat is being destroyed, but also due to native superstition. Besides being a general nuisance in villages, ancient Malagasy legend said the Aye-aye was a symbol of death.

Researchers in Madagascar report remarkable fearlessness in the aye-aye; some accounts tell of individual animals strolling nonchalantly in village streets or even walking right up to naturalists in the rainforest and sniffing their shoes. [14]

However, public contempt goes beyond this. The aye-aye is often viewed as a harbinger of evil and killed on sight. Others believe, should one point its narrow middle finger at someone, they are condemned to death. Some say the appearance of an aye-aye in a village predicts the death of a villager, and the only way to prevent this is to kill it. The Sakalava people go so far as to claim aye-ayes sneak into houses through the thatched roofs and murder the sleeping occupants by using their middle finger to puncture the victim's aorta.[15]

References

edit- ^ a b Groves 2005, p. 121.

- ^ a b Mittermeier et al. 2008, pp. ??.

- ^ a b IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011.2.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|assessment_year=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|assessors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|taxon=ignored (help) {{cite iucn}}: error: no identifier (help) - ^ Nowak 1999, pp. 533–534.

- ^ Sterling 2003, p. 1348....

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 2006, pp. 405–415.

- ^ Ruud 1970, pp. ??.

- ^ Simons & Meyers 2001, p. ??.

- ^ a b Ankel-Simons 2007, p. ??.

- ^ a b Yoder, Vilgalys & Ruvolo 1996, pp. ??.

- ^ "Aye-Aye". Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. 2006-10-26. Retrieved 2011-12-21.

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 605–606.

- ^ Mittermeier et al. 2010, p. 609.

- ^ Harmless Creature Killed Because of Superstition, David Knowles, March 27, 2010

- ^ Piper, Ross (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Greenwood Press.

Literature cited

edit- Ankel-Simons, F. (2007). Primate Anatomy (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-372576-9.

- Beck, R. M. D. (2009). "Was the Oligo-Miocene Australian metatherian Yalkaparidon a 'mammalian woodpecker'?". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 97 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01171.x.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Primates". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 111–184. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Konstant, W.R.; Hawkins, F.; Louis, E.E.; et al. (2006). Lemurs of Madagascar. Illustrated by S.D. Nash (2nd ed.). Conservation International. ISBN 1-881173-88-7. OCLC 883321520.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Louis, E.E.; Richardson, M.; Schwitzer, C.; et al. (2010). Lemurs of Madagascar. Illustrated by S.D. Nash (3rd ed.). Conservation International. ISBN 978-1-934151-23-5. OCLC 670545286.

- Mittermeier, R. A.; Ganzhorn, J. U.; Konstant, W. R.; Glander, K.; Tattersall, I.; Groves, C. P.; Rylands, A. B.; Hapke, A.; Ratsimbazafy, J.; Mayor, M. I.; Louis, E. E.; Rumpler, Y.; Schwitzer, C.; Rasoloarison, R. M. (2008). "Lemur Diversity in Madagascar" (PDF). International Journal of Primatology. 29 (6): 1607–1656. doi:10.1007/s10764-008-9317-y. S2CID 17614597.

- Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9.

- Quinn, A.; Wilson, D. E. (2004). "Daubentonia madagascariensis". Mammalian Species. 740: 1–6. doi:10.1644/740. S2CID 198129275.

- Ruud, J. (1970). Taboo: A Study of Malagasy Customs and Beliefs (2nd ed.). Oslo University Press. ASIN B0006FE92Y.

- Simons, E. L.; Meyers, D. M. (2001). "Folklore and Beliefs about the Aye aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis)" (PDF). Lemur News. 6: 11–16.

- Sterling, E. (2003). "Daubentonia madagascariensis, Aye-aye, Aye-aye". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1348–1351. ISBN 0-226-30306-3.

- Yoder, A. D.; Vilgalys, R.; Ruvolo, M. (1996). "Molecular evolutionary dynamics of cytochrome b in strepsirrhine primates: The phylogenetic significance of third-position transversions" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 13 (10): 1339–1350. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025580. PMID 8952078.