Varicella zoster virus (VZV), also known as human herpesvirus 3 (HHV-3, HHV3) or Human alphaherpesvirus 3 (taxonomically), is one of nine known herpes viruses that can infect humans. It causes chickenpox (varicella) commonly affecting children and young adults, and shingles (herpes zoster) in adults but rarely in children. As a late complication of VZV infection, Ramsay Hunt syndrome type 2 may develop in rare cases. VZV infections are species-specific to humans. The virus can survive in external environments for a few hours.[3]

| Human alphaherpesvirus 3 | |

|---|---|

| |

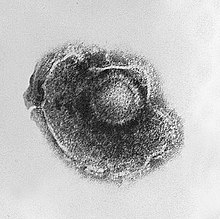

| Electron micrograph of a Human alphaherpesvirus 3 virion | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Duplodnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Heunggongvirae |

| Phylum: | Peploviricota |

| Class: | Herviviricetes |

| Order: | Herpesvirales |

| Family: | Orthoherpesviridae |

| Genus: | Varicellovirus |

| Species: | Human alphaherpesvirus 3

|

| Synonyms | |

VZV multiplies in the tonsils, and causes a wide variety of symptoms. Similar to the herpes simplex viruses, after primary infection with VZV (chickenpox), the virus lies dormant in neurons, including the cranial nerve ganglia, dorsal root ganglia, and autonomic ganglia. Many years after the person has recovered from initial chickenpox infection, VZV can reactivate to cause shingles.[4]

Epidemiology

editChickenpox

editPrimary varicella zoster virus infection results in chickenpox (varicella), which may result in complications including encephalitis, pneumonia (either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia), or bronchitis (either viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis). Even when clinical symptoms of chickenpox have resolved, VZV remains dormant in the nervous system of the infected person (virus latency), in the trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia.[5] VZV enters through the respiratory system and has an incubation period of 10–21 days, with an average of 14 days. Targeting the skin and peripheral nerves, the period of illness lasts about 3 to 4 days. Infected individuals are most contagious 1–2 days before the lesions appear. Signs and symptoms include vesicles that fill with pus, rupture, and scab before healing. Lesions most commonly occur on the face, throat, the lower back, the chest and shoulders.[6]

Shingles

editIn about a third of cases,[7] VZV reactivates in later life, producing a disease known as shingles or herpes zoster. The individual lifetime risk of developing herpes zoster is thought to be between 20% and 30%, or approximately 1 in 4 people. However, for people aged 85 and over, this risk increases to 1 in 2.[8] In a study in Sweden by Nilsson et al. (2015) the annual incidence of herpes zoster infection is estimated at a total of 315 cases per 100,000 inhabitants for all ages and 577 cases per 100,000 for people 50 years of age or older.[9]

VZV can also infect the central nervous system, with a 2013 article reporting an incidence rate of 1.02 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in Switzerland, and an annual incidence rate of 1.8 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in Sweden.[10]

Shingles lesions and the associated pain, often described as burning, tend to occur on the skin that is innervated by one or two adjacent sensory nerves, almost always on one side of the body only. The skin lesions usually subside over the course of several weeks, while the pain often persists longer. In 10–15% of cases the pain persists more than three months, a chronic and often disabling condition known as postherpetic neuralgia. Other serious complications of varicella zoster infection include Mollaret's meningitis, zoster multiplex, and inflammation of arteries in the brain leading to stroke,[11] myelitis, herpes ophthalmicus, or zoster sine herpete. In Ramsay Hunt syndrome, VZV affects the geniculate ganglion giving lesions that follow specific branches of the facial nerve. Symptoms may include painful blisters on the tongue and ear along with one-sided facial weakness and hearing loss. After infection during initial stages of pregnancy, the fetus can be severely damaged. Reye's syndrome can happen after initial infection, causing continuous vomiting and signs of brain dysfunction such as extreme drowsiness or combative behavior. In some cases, death or coma can follow. Reye's syndrome mostly affects children and teenagers; using aspirin during infection can increase this risk.[6]

Morphology

editVZV is closely related to the herpes simplex viruses (HSV), sharing much genome homology. The known envelope glycoproteins (gB, gC, gE, gH, gI, gK, gL) correspond with those in HSV; however, there is no equivalent of the HSV gD protein. VZV also fails to produce the LAT (latency-associated transcripts) that play an important role in establishing HSV latency (herpes simplex virus).[12] VZV virions are spherical and 180–200 nm in diameter. Their lipid envelope encloses the 100 nm nucleocapsid of 162 hexameric and pentameric capsomeres arranged in an icosahedral form. Its DNA is a single, linear, double-stranded molecule, 125,000 nt long. The capsid is surrounded by loosely associated proteins known collectively as the tegument; many of these proteins play critical roles in initiating the process of virus reproduction in the infected cell. The tegument is in turn covered by a lipid envelope studded with glycoproteins that are displayed on the exterior of the virion, each approximately 8 nm long.[13]

Genomes

editThe genome was first sequenced in 1986.[14] It is a linear duplex DNA molecule, a laboratory strain has 124,884 base pairs. The genome has two predominant isomers, depending on the orientation of the S segment, P (prototype) and IS (inverted S) which are present with equal frequency for a total frequency of 90–95%. The L segment can also be inverted resulting in a total of four linear isomers (IL and ILS). This is distinct from HSV's equiprobable distribution, and the discriminatory mechanism is not known. A small percentage of isolated molecules are circular genomes, about which little is known. (It is known that HSV circularizes on infection.) There are at least 70 open reading frames in the genome.

Evolution

editCommonality with HSV1 and HSV2 indicates a common ancestor; five genes (out of about 70) do not have corresponding HSV genes. Relation with other human herpes viruses is less strong, but many homologues and conserved gene blocks are still found.

There are at least five clades of this virus.[15] Clades 1 and 3 include European/North American strains; clade 2 are Asian strains, especially from Japan; and clade 5 appears to be based in India. Clade 4 includes some strains from Europe but its geographic origins need further clarification. There are also four genotypes that do not fit into these clades.[16] Allocation of VZV strains to clades required the sequence of whole virus genome. Practically all molecular epidemiological data on global VZV strains distribution are obtained with targeted sequencing of selected regions.

Phylogenetic analysis of VZV genomic sequences resolves wild-type strains into nine genotypes (E1, E2, J, M1, M2, M3, M4, VIII and IX).[17][18] Complete sequences for M3 and M4 strains are unavailable, but targeted analyses of representative strains suggest they are stable, circulating VZV genotypes. Sequence analysis of VZV isolates identified both shared and specific markers for every genotype and validated a unified VZV genotyping strategy. Despite high genotype diversity no evidence for intra-genotypic recombination was observed. Five of seven VZV genotypes were reliably discriminated using only four single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) present in ORF22, and the E1 and E2 genotypes were resolved using SNP located in ORF21, ORF22 or ORF50. Sequence analysis of 342 clinical varicella and zoster specimens from 18 European countries identified the following distribution of VZV genotypes: E1, 221 (65%); E2, 87 (25%); M1, 20 (6%); M2, 3 (1%); M4, 11 (3%). No M3 or J strains were observed.[17] Of 165 clinical varicella and zoster isolates from Australia and New Zealand typed using this approach, 67 of 127 eastern Australian isolates were E1, 30 were E2, 16 were J, 10 were M1, and 4 were M2; 25 of 38 New Zealand isolates were E1, 8 were E2, and 5 were M1.[19]

The mutation rate for synonymous and nonsynonymous mutation rates among the herpesviruses have been estimated at 1 × 10−7 and 2.7 × 10−8 mutations/site/year, respectively, based on the highly conserved gB gene.[20]

Treatment

editWithin the human body it can be treated by a number of drugs and therapeutic agents including acyclovir for chickenpox, famciclovir, valaciclovir for the shingles, zoster-immune globulin (ZIG), and vidarabine.[21] Acyclovir is frequently used as the drug of choice in primary VZV infections, and beginning its administration early can significantly shorten the duration of any symptoms. However, reaching an effective serum concentration of acyclovir typically requires intravenous administration, making its use more difficult outside of a hospital.[22]

Vaccination

editA live attenuated VZV Oka/Merck strain vaccine is available and is marketed in the United States under the trade name Varivax. It was developed by Merck, Sharp & Dohme in the 1980s from the Oka strain virus isolated and attenuated by Michiaki Takahashi and colleagues in the 1970s. It was submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for approval in 1990 and was approved in 1995. Since then, it has been added to the recommended vaccination schedules for children in Australia, the United States, and many other countries. Varicella vaccination has raised concerns in some that the immunity induced by the vaccine may not be lifelong, possibly leaving adults vulnerable to more severe disease as the immunity from their childhood immunization wanes. Vaccine coverage in the United States in the population recommended for vaccination is approaching 90%, with concomitant reductions in the incidence of varicella cases and hospitalizations and deaths due to VZV.[citation needed] So far, clinical data has proved that the vaccine is effective for over ten years in preventing varicella infection in healthy individuals, and when breakthrough infections do occur, illness is typically mild.[23] In 2006, the CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended a second dose of vaccine before school entry to ensure the maintenance of high levels of varicella immunity.[24]

In 2006, the FDA approved Zostavax for the prevention of shingles. Zostavax is a more concentrated formulation of the Varivax vaccine, designed to elicit an immune response in older adults whose immunity to VZV wanes with advancing age. A systematic review by Cochrane (updated in 2023) shows that Zostavax reduces the incidence of shingles by almost 50%.[25]

Shingrix is a subunit vaccine (HHV3 glycoprotein E) developed by GlaxoSmithKline which was approved in the United States by the FDA in October 2017.[26] The ACIP recommended Shingrix for adults over the age of 50, including those who have already received Zostavax. The committee voted that Shingrix is preferred over Zostavax for the prevention of zoster and related complications because phase 3 clinical data showed vaccine efficacy of >90% against shingles across all age groups, as well as sustained efficacy over a four-year follow-up. Unlike Zostavax, which is given as a single shot, Shingrix is given as two intramuscular doses, two to six months apart.[27] This vaccine has shown to be immunogenic and safe in adults with human immunodeficiency virus.[28]

History

editChickenpox-like rashes were recognized and described by ancient civilizations; the relationship between zoster and chickenpox was not realized until 1888.[29] In 1943, the similarity between virus particles isolated from the lesions of zoster and those from chickenpox was noted.[30] In 1974 the first chickenpox vaccine was introduced.[31]

The varicella zoster virus was first isolated by Evelyn Nicol while she was working at Cleveland City Hospital.[32] Thomas Huckle Weller also isolated the virus and found evidence that the same virus was responsible for both chickenpox and herpes zoster.[33]

The etymology of the name of the virus comes from the two diseases it causes, varicella and herpes zoster. The word varicella is possibly derived from variola, a term for smallpox coined by Rudolph Augustin Vogel in 1764.[34]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "ICTV 9th Report (2011) Herpesviridae". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Archived from the original on December 22, 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

Human herpesvirus 3 Human herpesvirus 3 [X04370=NC_001348] (HHV-3) (Varicella-zoster virus)

- ^ "ICTV Taxonomy history: Human alphaherpesvirus 3". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "Pathogen Safety Data Sheets: Infectious Substances – Varicella-zoster virus". canada.ca. Pathogen Regulation Directorate, Public Health Agency of Canada. 2012-04-30. Retrieved 2017-10-10.

- ^ Nagel MA, Gilden DH (July 2007). "The protean neurologic manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 74 (7): 489–94, 496, 498–9 passim. doi:10.3949/ccjm.74.7.489. PMID 17682626.

- ^ Steiner I, Kennedy PG, Pachner AR (November 2007). "The neurotropic herpes viruses: herpes simplex and varicella-zoster". The Lancet. Neurology. 6 (11): 1015–28. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70267-3. PMID 17945155. S2CID 6691444.

- ^ a b Tortora G. Microbiology: An Introduction. Pearson. pp. 601–602.

- ^ Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF (June 2008). "Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 57 (RR-5): 1–30, quiz CE2-4. PMID 18528318.

- ^ Pinchinat S, Cebrián-Cuenca AM, Bricout H, Johnson RW (April 2013). "Similar herpes zoster incidence across Europe: results from a systematic literature review". BMC Infectious Diseases. 13 (1): 170. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-170. PMC 3637114. PMID 23574765.

- ^ Nilsson J, Cassel T, Lindquist L (May 2015). "Burden of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in Sweden". BMC Infectious Diseases. 15: 215. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0951-7. PMC 4493830. PMID 26002038.

- ^ Becerra JC, Sieber R, Martinetti G, Costa ST, Meylan P, Bernasconi E (July 2013). "Infection of the central nervous system caused by varicella zoster virus reactivation: a retrospective case series study". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 17 (7): e529-34. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2013.01.031. PMID 23566589.

- ^ Nagel MA, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Wellish MC, Forghani B, Schiller A, et al. (March 2008). "The varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: clinical, CSF, imaging, and virologic features". Neurology. 70 (11): 853–60. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000304747.38502.e8. PMC 2938740. PMID 18332343.

- ^ Arvin AM (July 1996). "Varicella-zoster virus". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 9 (3): 361–81. doi:10.1128/CMR.9.3.361. PMC 172899. PMID 8809466.

- ^ Han DH (25 October 2017). "General Characteristics and Epidemiology of varicella-zoster virus (VZV)". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Medical Professionals Reference (MPR). Retrieved 2021-06-14.

- ^ Davison AJ, Scott JE (September 1986). "The complete DNA sequence of varicella-zoster virus". The Journal of General Virology. 67 (9): 1759–816. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-67-9-1759. PMID 3018124.

- ^ Chow VT, Tipples GA, Grose C (August 2013). "Bioinformatics of varicella-zoster virus: single nucleotide polymorphisms define clades and attenuated vaccine genotypes". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 18: 351–6. Bibcode:2013InfGE..18..351C. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2012.11.008. PMC 3594394. PMID 23183312.

- ^ Grose C (September 2012). "Pangaea and the Out-of-Africa Model of Varicella-Zoster Virus Evolution and Phylogeography". Journal of Virology. 86 (18): 9558–65. doi:10.1128/JVI.00357-12. PMC 3446551. PMID 22761371.

- ^ a b Loparev VN, Rubtcova EN, Bostik V, Tzaneva V, Sauerbrei A, Robo A, et al. (January 2009). "Distribution of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) wild-type genotypes in northern and southern Europe: evidence for high conservation of circulating genotypes". Virology. 383 (2): 216–25. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.026. PMID 19019403.

- ^ Zell R, Taudien S, Pfaff F, Wutzler P, Platzer M, Sauerbrei A (February 2012). "Sequencing of 21 varicella-zoster virus genomes reveals two novel genotypes and evidence of recombination". Journal of Virology. 86 (3): 1608–22. doi:10.1128/JVI.06233-11. PMC 3264370. PMID 22130537.

- ^ Loparev VN, Rubtcova EN, Bostik V, Govil D, Birch CJ, Druce JD, et al. (December 2007). "Identification of five major and two minor genotypes of varicella-zoster virus strains: a practical two-amplicon approach used to genotype clinical isolates in Australia and New Zealand". Journal of Virology. 81 (23): 12758–65. doi:10.1128/JVI.01145-07. PMC 2169114. PMID 17898056.

- ^ McGeoch DJ, Cook S (April 1994). "Molecular phylogeny of the alphaherpesvirinae subfamily and a proposed evolutionary timescale". Journal of Molecular Biology. 238 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1264. PMID 8145260.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (March 2012). "FDA approval of an extended period for administering VariZIG for postexposure prophylaxis of varicella" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 61 (12): 212. PMID 22456121.

- ^ Cornelissen CN (2013). Lippincott's illustrated reviews: Microbiology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health. pp. 255–272.

- ^ "Prevention of varicella: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 45 (RR-11): 1–36. July 1996. PMID 8668119.

- ^ Marin M, Güris D, Chaves SS, Schmid S, Seward JF, et al. (Advisory Committee On Immunization Practices) (June 2007). "Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 56 (RR-4): 1–40. PMID 17585291.

- ^ de Oliveira Gomes J, Gagliardi AM, Andriolo BN, Torloni MR, Andriolo RB, Puga ME, Canteiro Cruz E (October 2023). "Vaccines for preventing herpes zoster in older adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (10): CD008858. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008858.pub5. PMC 10542961. PMID 37781954.

- ^ Gruber MF (20 October 2017). "Biologics License Application (BLA) for Zoster Vaccine Recombinant, Adjuvant" (PDF). Office of Vaccines Research and Review, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ Han HD (25 October 2017). "ACIP: New Vaccine Recommendations for Shingles Prevention". Medical Professionals Reference (MPR). Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Berkowitz EM, Moyle G, Stellbrink HJ, Schürmann D, Kegg S, Stoll M, et al. (April 2015). "Safety and immunogenicity of an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit candidate vaccine in HIV-infected adults: a phase 1/2a randomized, placebo-controlled study". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 211 (8): 1279–87. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiu606. PMC 4371767. PMID 25371534.

- ^ Wood MJ (October 2000). "History of Varicella Zoster Virus". Herpes: The Journal of the IHMF. 7 (3): 60–65. PMID 11867004.

- ^ Ruska H (1943). "Über das Virus der Varicellen und des Zoster". Klin Wochenschr. 22 (46–47): 703–704. doi:10.1007/bf01768631. S2CID 11118674.

- ^ Takahashi M, Otsuka T, Okuno Y, Asano Y, Yazaki T (November 1974). "Live vaccine used to prevent the spread of varicella in children in hospital". Lancet. 2 (7892): 1288–90. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90144-5. PMID 4139526.

- ^ Frellick M (July 1, 2020). "Pioneering Molecular Biologist Dies of COVID-19 at 89". Medscape. Retrieved Sep 19, 2022.

- ^ Ligon BL (January 2002). "Thomas Huckle Weller MD: Nobel Laureate and research pioneer in poliomyelitis, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, rubella, and other infectious diseases". Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 13 (1): 55–63. doi:10.1053/spid.2002.31314. PMID 12118846.

- ^ "Etymologia: Varicella Zoster Virus". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 21 (4): 698. 2015. doi:10.3201/eid2104.ET2104. PMC 4378502.

External links

edit- "Varicella (Chickenpox) Vaccination". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2017-07-07.