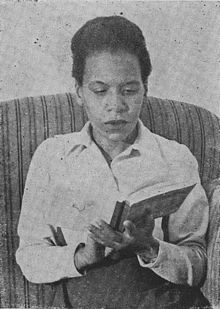

Virginia Brindis de Salas (18 September 1908 – 6 April 1958)[1] was a poet of the black community of Uruguay. The country's leading black woman poet, she is also considered "the most militant among Afro-Uruguayan writers".[2] Her poetry addresses the social reality of Black Uruguayans.[3] Her writings made her, along with fellow Afro-Uruguayan Pilar Barrios, one of the few published Uruguayan women poets.[4]

Early life

editVirginia Brindis de Salas was born in Montevideo,[1] Uruguay, the daughter of José Salas and María Blanca Rodríguez,[5] Little is known about her life; according to Joy Elizondo, she claimed to be the niece of Cuban violinist Claudio Brindis de Salas,[3] though this is unsubstantiated.

Career

editBrindis de Salas was an active contributor to the black artistic journal Nuestra Raza.[3] She published two collections of poetry. The first, Pregón de Marimorena ("The Call of Mary Morena"), came out in 1946,[6] bringing her a certain amount of recognition. Chilean Nobel laureate Gabriela Mistral wrote of Brindis de Salas: "Sing, beloved Virginia, you are the only one of your race who represents Uruguay. Your poetry is known in Los Angeles and in the West. I have heard of your recent work through diplomatic friends, and, may God grant that this book be the key that opens coffers of luck to the only brave black Uruguayan woman that I know."[7] In 1949 Brindis de Salas issued Cien Cárceles de Amor ("One Hundred Prisons of Love"),[8] which is divided into four sections that each highlight a different type of African-derived music: "Ballads", "Calls", "Tangos" and "Songs".[3]

According to Caroll Mills Young, in both collections Brindis de Salas "poetically evokes the social and cultural reality of Afro-Uruguay.... The volumes are intended to promote social change in Uruguay; they exemplify the poet's crusade for solidarity, equality, and dignity."[9]

In the prologue to Cien Cárceles de Amor Brindis de Salas mentioned a forthcoming third volume entitled Cantos de lejanía ("Songs from Faraway"), but this book was never published.[3]

References

edit- ^ a b "Brindis de Salas, Virginia", Autores.uy.

- ^ Caroll Mills Young, "The Unmasking of Virginia Brindis de Salas: Minority Discourse of Afro-Uruguay", in Miriam DeCosta-Willis, Daughters of the Diaspora: Afra-Hispanic Writers, Ian Randle Publishers, 2003, pp. 11–24.

- ^ a b c d e Joy Elizondo, "Brindis de Salas, Virginia" in Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (eds), Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 626 –627.

- ^ Faculty Senate: Faculty Achievement Database - Marshall University

- ^ "BRINDIS DE SALAS 'The Black Paganini'. Parental Denial of a Genius", TheCubanHistory.com, 28 January 2016.

- ^ Marvin A. Lewis, Afro-Uruguayan Literature: Post-colonial Perspectives, Bucknell University Press, 2003, p. 89.

- ^ Quoted in Caroll Mills Young, "The Unmasking of Virginia Brindis de Salas: Minority Discourse of Afro-Uruguay", in Miriam DeCosta-Willis, Daughters of the Diaspora: Afra-Hispanic Writers (2003), pp. 18.

- ^ Margaret Busby (ed.), "Virginia Brindis de Salas", Daughters of Africa, Jonathan Cape, 1992, p. 228.

- ^ Caroll Mills Young, in Miriam DeCosta-Willis, Daughters of the Diaspora (2003), p. 22.

Further reading

edit- Marvin A. Lewis, Afro-Uruguayan Literature: Post-colonial Perspectives, Bucknell University Press, 2003, pp. 87–93.

- Caroll Mills Young, "The Unmasking of Virginia Brindis de Salas: Minority Discourse of Afro-Uruguay", in Miriam DeCosta-Willis, Daughters of the Diaspora: Afra-Hispanic Writers, Ian Randle Publishers, 2003, pp. 11–24.