- The volcano system in Iceland that started activity on August 17, 2014, and ended on February 27, 2015, is Bárðarbunga.

- The volcano in Iceland that erupted in May 2011 is Grímsvötn.

Iceland experiences frequent volcanic activity, due to its location both on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a divergent tectonic plate boundary, and being over a hotspot. Nearly thirty volcanoes are known to have erupted in the Holocene epoch; these include Eldgjá, source of the largest lava eruption in human history. Some of the various eruptions of lava, gas and ash have been both destructive of property and deadly to life over the years, as well as disruptive to local and European air travel.

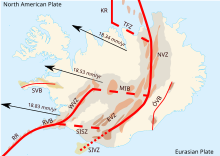

RR, Reykjanes Ridge; RVB, Reykjanes Volcanic Belt; WVZ, West Volcanic Zone; MIB, Mid-Iceland Belt; SISZ, South Iceland Seismic Zone; EVZ, East Volcanic Zone; SIVZ, South Iceland Volcanic Zone; NVZ, North Volcanic Zone; TFZ, Tjörnes Fracture Zone; KR, Kolbeinsey Ridge; ÖVB, Öræfajökul Volcanic Belt; SVB, Snæfellsnes Volcanic Belt.

1) Snæfellsjökull, 2) Ljósufjöll, 3) Reykjanes, 4) Svartsengi, 5) Fagradalsfjall, 6) Krýsuvík, 7) Brennisteinsfjöll, 8) Hengill, 9) Surtsey, 10) Eldfell, 11) Eyjafjallajökull, 12) Hekla, 13) Katla, 14) Lakagigar, 15) Öræfajökull, 16) Grímsvötn, 17) Bárðarbunga, 18) Hofsjökull, 19) Langjökull, 20) Askja, 21) Krafla, 22) Þeistareykjabunga

Volcanic systems and volcanic zones of Iceland

editHolocene volcanism in Iceland is mostly to be found in the Neovolcanic Zone, comprising the Reykjanes volcanic belt (RVB), the West volcanic zone (WVZ), the Mid-Iceland belt (MIB), the East volcanic zone (EVZ) and the North volcanic zone (NVZ). Two lateral volcanic zones play a minor role: Öræfi volcanic belt (ÖVB also known as Öræfajökull volcanic system) and Snæfellsnes volcanic belt (SVB).[1] Outside of the main island are the Reykjanes Ridge (RR), as part of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge to the south-west and the Kolbeinsey Ridge (KR) to the north. Two transform zones are connecting these volcano-tectonic zones: the South Iceland seismic zone (SISZ) in the south of Iceland and the Tjörnes transform zone (TFZ) in the north.

The island has around 30 active volcanic systems. Within each are volcano-tectonic fissure systems and many, but not all of them, also have at least one central volcano (mostly in the form of a stratovolcano, sometimes of a shield volcano with a magma chamber underneath). Several classifications of the systems exist, for example there is one of 30 systems,[2]: 10 and one of 34 systems, with the later currently being used in Iceland itself.[3] There are 23 central volcanoes using the definition that they: erupt frequently; extrude either basaltic, intermediate or felsic lavas; have an associated shallow crustal magma chamber, and are often associated with collapse caldera or fissure systems.[2]: 11 Shield volcanoes, as the term is used in the Iceland context, tend to erupt only once, so have monogenetic characteristics. However many shield volcanoes outside Iceland are associated with oceanic island volcanism such as in Hawaii where they have been built up over many eruptions.[2]: 11–12 Fissure vents in Iceland tend to produce calmer effusive eruptions, but can be associated with large volumes of lava (flood basalt events) and some have had prolonged eruptions with numerous eruptive episodes, lasting for years.[2]: 12–13

Up to 2008, thirteen of the volcanic systems had hosted eruptions since the settlement of Iceland in AD 874.[4] Nearly thirty volcanoes are known to have erupted in the Holocene epoch and so are active.[5]

Of these active volcanic systems, the most active is Grímsvötn.[6] Over the past 500 years, Iceland's volcanoes have produced a third of the total global lava output.[7] Current productivity, which is known to be cyclical, has been estimated to be between 0.05–0.08 km3 (0.012–0.019 cu mi) per year which is higher than the output rate of the Hawaiian volcanoes, and would be double or even triple this figure if intrusive volumes are included.[4]: 205

Volcano tectonics

editThe types of eruptions most likely in a particular Icelandic volcanic system or zone are now understood. Earthquakes and volcanism have patterns in time and place that can be combined into a consistent tectonic process that is explained by the geological deformation of Iceland. In summary in Iceland there are four main types of tectonic zones:[8]

- Spreading zones of rifting and volcanism producing the predominant Iceland tholeiitic basaltic crust

- Fracture zones connecting offset branches of the spreading zones which includes the SISZ

- Trans-tensional zones with transform faulting and spreading of which are the RVB and TFZ

- Flank zones with stratovolcanoes and minor rifting with alkalic to transitional volcanic rocks over the crust

These tectonic zones result from the interaction of combination of the spreading activity of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge which is spreading in a general east and west direction while the mantle plume activity that results in the hotspot, has been migrating over at least the last 25 million years in a west to slightly south-east direction.[2]: 4–6

Geology

editMorphology

editFissure vents are found predominantly in what are termed fissure swarms (a combination of tectonic related fissures and faults) that are also associated with crater rows and smaller cinder or spatter cones.[9] Where such eruptions interact with water the eruptions become more explosive and these phreatomagmatic eruptions produce tephra and possibly maars and tuff rings or cones.[8][9]

Composition

editThe composition of the lava reflects the tectonic factors above and are consistent with the influence of the hotspot so the trend is for ocean island basalts (OIB) type to predominate over mid ocean ridge basalts (MORB) which are only found in the north of the NVZ.[10]: 133–4 The compositional series are thus tholeiitic basalt, transitional alkalic basalts and alkalic (felsic).[10]: 134

Large extrusive, predominantly tholeiitic basaltic lava fields and shields with theoleiitic lava are the predominant material erupted and are found in the RVB, WVZ, MIB, EVZ and NVZ.[3] They are associated with divergence tectonics of the ridge plate boundaries.[8]: 40 Central volcanoes, with associated fissure swarms are typical, except in the RVB. Hengill is the only active central volcano in the far east of the RVB, and this is likely to be because here a triple junction exists, resulting in a volcano with some rhyolytic and dacite components due to the complexity of its rift propagation formation.[11][12]: 1128 The island of Eldey off the south-west of the RVB has similar geological formations to the RVB but has a basalt composition with tholeiites and picrites.[13] Hofsjökull, a large volcano with a caldera and rhyolite lavas in the MIB has explosive eruption potential but has not erupted underneath its ice cover for several thousand years and its companion Kerlingarfjöll for even longer.[14]

Arc volcanism has been thought to be occurring in the Snæfellsnes volcanic belt with alkaline magma series volcanism in the stratovolcanoes such as Snæfellsjökull which usually erupt effusive basaltic lava but can have infrequent explosive silicic eruptions followed by extrusion of intermediate composition lava.[15] However the modelling of the processes involved is incomplete and almost certainly involves primarily fractional crystallization of primary basaltic magma with limited input from pre-existing crustal material as is the case in arc volcanism.[16] The ÖVB is represented by the Öræfajökull (Hnappafellsjökull) stratovolcano which has a history of violent rhyolite to alkali basalt eruptions with tephra volumes up to 10 km3 (2.4 cu mi) and accompanying jökulhlaup.[17]

The island Vestmannaeyjar volcano to the south east of Iceland has in its recent activity formed the island of Surtsey and cones such as Eldfell on Heimaey. It is the southern tip of the EVZ propagating rift in what is an off rift region called the South Iceland Volcanic Zone (SIVZ),[18] and the older alkaline basalts were alkali olivine and more recent mugearite in composition.[19] The basalts of the southern EVZ on land are rarely silicic but the volcanoes can have explosive phreatomagmatic eruptions.[20]

Overall the surface area of post glacial erupted rocks of Iceland is 92% basalt, 4% basaltic andesites, 1% andesites, and 3% dacite-rhyolites.[21]

Important eruptions

editSee also : List of volcanic eruptions in Iceland

Largest Holocene eruptions

editDue to incomplete surveys, which also need to be confined to subaerial eruptions and not include igneous intrusions, the accumulative amounts of dense-rock equivalent erupted in Iceland will be underestimated.[4] The amounts known are some of the most significant contributions to recent eruptive volumes on Earth.[4] Since the last ice age 91% of the magma erupted in Iceland has been mafic, 6% intermediate in composition and 3% silicic.[4]: 203 The number of eruptions estimated in this 11,700 odd year period can only be an approxiamate figure,[a] but about three to four explosive ones occur for every purely effusive one.[4]: 203

| Volcanic Zone or Belt | Lava DRE[b] | Tephra DRE[c] | Total DRE[b][c] | Number eruptions[a] | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern volcanic zone | 175.2 km3 (42.0 cu mi) | 164.3 km3 (39.4 cu mi) | 339.4 km3 (81.4 cu mi) | 2026 | [23][24][25] Includes individual eruptions from Laki 15.1 km3 (3.6 cu mi), Eldgjá 19.6 km3 (4.7 cu mi) and Þjórsá Lava 25.0 km3 (6.0 cu mi).[4] |

| Western volcanic zone | 94.0 km3 (22.6 cu mi) | 0.0 km3 (0.0 cu mi) | 94.0 km3 (22.6 cu mi) | 47 | |

| Northern volcanic zone | 90.7 km3 (21.8 cu mi) | 3.3 km3 (0.8 cu mi) | 94.0 km3 (22.6 cu mi) | 146 | |

| Reykjanes volcanic belt | 22.3 km3 (5.3 cu mi) | 22.0 km3 (5.3 cu mi) | 29.2 km3 (7.0 cu mi) | 151 | [26] Ongoing as of 2024 |

| Snæfellsnes volcanic belt | 7.7 km3 (1.8 cu mi) | 1.3 km3 (0.3 cu mi) | 9.0 km3 (2.2 cu mi) | 57 | |

| Öræfajökull volcanic belt | 0.6 km3 (0.1 cu mi) | 2.4 km3 (0.6 cu mi) | 3.0 km3 (0.7 cu mi) | 8 | |

| Mid-Iceland belt | 1.0 km3 (0.2 cu mi) | 0.0 km3 (0.0 cu mi) | 1.0 km3 (0.2 cu mi) | 9 |

Hekla

editHekla has erupted more than 20 times in recorded history. It was known to medieval Europeans as the Gate of Hell; that reputation persisted into the 19th century.[27]

Laki/Skaftáreldar 1783-84

editThe most deadly volcanic eruption of Iceland's history was the so-called Skaftáreldar (fires of Skaftá) in 1783-1784.[28] The eruption was in the crater row Lakagígar (craters of Laki) southwest of Vatnajökull glacier. The craters are a part of a larger volcanic system with the subglacial Grímsvötn as a central volcano. Roughly a fifth of the Icelandic population died because of the eruption.[28] Most died not because of the lava flow or other direct effects of the eruption but from indirect effects, including changes in climate and illnesses in livestock in the following years caused by the ash and poisonous gases from the eruption.[28] The eruption resulted in the second largest basaltic lava flow from a single eruption in historic times.[29]

Eldfell 1973

editEldfell is a volcanic cone on the east side of the island of Heimaey which formed during an eruption in January 1973.[30] The eruption happened without warning, causing the island's population of about 5,300 people to evacuate on fishing boats within a few hours. Importantly, the progress of lava into the harbour was slowed by manual spraying of seawater. One person died, and the eruption resulted in the destruction of homes and property on the island.[31]: 11

Eyjafjallajökull 2010

editThe eruption under Eyjafjallajökull in April 2010 caused extreme disruption to air travel across western and northern Europe over a period of six days in April 2010. About 20 countries closed their airspace to commercial jet traffic and it affected approximately 10 million travellers.[32]

The eruption had a VEI of 4, the largest known from Eyjafjallajökull.[33] Several previous eruptions of Eyjafjallajökull have been followed soon afterwards by eruptions of the larger volcano Katla, but after the 2010 eruption, no activity occurred at Katla.[34]

Grímsvötn 2011

editThe eruption in May 2011 at Grímsvötn under the Vatnajökull glacier sent thousands of tonnes of ash into the sky in a few days, raising concerns of the potential for travel chaos across northern Europe although only about 900 flights were initially disrupted.[35]

Holuhraun 2014–2015

editBárðarbunga is a stratovolcano and is roughly 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) above sea level in central Iceland, i.e. in the northern edge of Vatnajökull.[36] This makes it the second highest mountain in Iceland.

Hóluhraun is an older lavafield situated 50 km (31 mi) north-east of Bárðarbunga, 20 km (12 mi) south of Askja (last eruption 1961), at an altitude of about 700 m (2,300 ft). Here the eruption started on August 17, 2014, and lasted for 180 days.[37] The 2014-2015 eruption was Iceland's largest in 230 years.[38] Following a major earthquake swarm, multiple lava fountain eruptions began in Holuhraun.[39] The lava flow rate was between 250 and 350 m3/s (8,800 and 12,400 cu ft/s) and came from a dyke over 40 km (25 mi) long.[40][41] An ice-filled subsidence bowl over 100 km2 (39 sq mi) in area and up to 65 m (213 ft) deep formed as well.[37] There was very limited ash output from this eruption. The primary concern with this eruption was the large plumes of sulphur dioxide (SO2) in the atmosphere which adversely affected breathing conditions across Iceland, depending on wind direction. The volcanic cloud was also transported toward Western Europe in September 2014.[42]

Fagradalsfjall 2021-2022

editFollowing a three-week period of increased seismic activity, an eruption fissure developed near Fagradalsfjall,[43] a mountain on the Reykjanes Peninsula. Lava flow from a 200-meter fissure was first discovered by an Icelandic Coast Guard helicopter on March 19, 2021, in the Geldingadalur area near Grindavík, and within hours the fissure had grown to 500 m (1,600 ft) in length.[44]

Another eruption, very similar to the 2021 eruption, began on 3 August 2022,[45] and ceased on 21 August 2022.

Litli-Hrútur 2023

editOn 10 July 2023 at 16:40 UTC, a fissure eruption began adjacent to the summit of Litli-Hrútur.[46]

Sundhnúkur 2023-2024

editOn December 18, 2023, at 22:17 near Hagafell, the volcano began a fissure eruption.[47] In January, 2024 lava from this eruption destroyed 3 houses in the nearby town of Grindavík.[48]

Structure of lava fields

editThe smooth flowing basaltic lava pāhoehoe is known in Icelandic as helluhraun [ˈhɛtlʏˌr̥œyːn].[Islandsbok 1] It forms smooth surfaces that are quite easy to cross. More viscous lava forms ʻaʻā flows, known in Icelandic as apalhraun [ˈaːpalˌr̥œyːn].[Islandsbok 1] The loose, broken, sharp, spiny surface of an ʻaʻā flow makes hiking across it difficult, slow and dangerous, it is easy to stick a foot into a hole and break a leg.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b Number of eruptions is a ballpark figure.[4]: 202 See note on inadequacy DRE tephra Icelandic record for some reasons. Even today eruptions under a glacier might be suspected but not proved.

- ^ a b DRE for lava flows is known to be 50% inaccurate if based on the planimetric method rather than preeruption and posteruption digital elevation models.[22]

- ^ a b Inaccuracies in tephra DRE estimates are worse than for lava as: less than 35% of Holocene explosive eruptions have been associated with their tephra layer, Iceland's post-glacial tephra stratigraphy is incomplete and distribution of less than 10% of the known tephra layers have been mapped.[4]: 203

References

edit- ^ Thor Thordarson, Armann Hoskuldsson: Iceland. Classic geology of Europe 3. Harpenden 2002, p. 9

- ^ a b c d e Andrew, R. E. B. (2008). PhD Dissertation: Volcanotectonic Evolution and Characteristic Volcanism of the Neovolcanic Zone of Iceland (PDF) (Thesis). Georg-August-Universität, Göttingen. pp. 1–122. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2011-05-24.

- ^ a b "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Thordarson, T.; Hoskuldsson, A. (2008). "Postglacial Volcanism in Iceland" (PDF). Jökull. 58: 197–228. doi:10.33799/jokull2008.58.197.

- ^ "Global Volcanism Program | Holocene Volcano List".

- ^ Gudmundsson, Magnus Tumi; Larsen, G; Hoskuldsson, A; Gylfason, A.G. (2008). "Volcanic Hazards in Iceland". Jökull. 58: 251–268. doi:10.33799/jokull2008.58.251.

- ^ Waugh, David (2002). Geography: An Integrated Approach. United Kingdom: Nelson Thornes. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-17-444706-1.

- ^ a b c Sæmundsson, K.; Sigurgeirsson, M.Á.; Friðleifsson, G.Ó. (2020). "Geology and structure of the Reykjanes volcanic system, Iceland". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 391 (106501). Bibcode:2020JVGR..39106501S. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2018.11.022.: Introduction

- ^ a b Sigurgeirsson, Magnús Á.; Einarsson, Sigmundur (2019). "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes - Reykjanes and Svartsengi volcanic systems". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. Retrieved 3 January 2024.: Detailed Description

- ^ a b Jakobsson, S.P.; Jónasson, K.; Sigurdsson, I.A. (2008). "The three igneous rock series of Iceland" (PDF). Jökull. 58 (1): 117–138. doi:10.33799/jokull2008.58.117. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Kristján, Sæmundsson (2019). "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes - Hengill". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ Decriem, J.; Árnadóttir, T.; Hooper, A.; Geirsson, H.; Sigmundsson, F.; Keiding, M.; Ófeigsson, B. G.; Hreinsdóttir, S.; Einarsson, P.; LaFemina, P.; Bennett, R. A. (2010). "The 2008 May 29 earthquake doublet in SW Iceland". Geophysical Journal International. 181 (2): 1128–1146. Bibcode:2010GeoJI.181.1128D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246x.2010.04565.x.

- ^ Larsen, Guðrún (2019). "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes - Eldey". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. Retrieved 3 January 2023.: Detailed Description

- ^ Grönvold, Karl (2019). "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes - Hofsjökull". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ Jóhannesson, Haukur (2019). "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes - Snæfellsjökull". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Banik, T.J.; Carley, T.L.; Coble, M.A.; Hanchar, J.M.; Dodd, J.P.; Casale, G.M.; McGuire, S.P. = (2021). "Magmatic processes at Snæfell volcano, Iceland, constrained by zircon ages, isotopes, and trace elements". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 22 (3): p.e2020GC009255. Bibcode:2021GGG....2209255B. doi:10.1029/2020GC009255.

- ^ Höskuldsson, Ármann (2019). "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes - Öræfajökull". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Kahl, M; Bali, E.; Guðfinnsson, G.H.; Neave, D.A.; Ubide, T.; van der Meer, Q.H.A.; Matthews, S. (2021). "Conditions and Dynamics of Magma Storage in the Snæfellsnes Volcanic Zone, Western Iceland: Insights from the Búðahraun and Berserkjahraun Eruptions". Journal of Petrology. 62 (9). doi:10.1093/petrology/egab054.

- ^ Höskuldsson, Ármann (2019). "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes - Vestmannaeyjar". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. Retrieved 3 January 2024.: Detailed Description

- ^ Larsen, Guðrún; Guðmundsson, Magnús T. (2019). "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes - Katla". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. Retrieved 4 January 2024.: Detailed Description

- ^ Sigmundsson, F.; Einarsson, P.; Hjartardóttir, Á.R.; Drouin, V.; Jónsdóttir, K.; Arnadottir, T.; Geirsson, H.; Hreinsdottir, S.; Li, S.; Ofeigsson, B.G. (2020). "Geodynamics of Iceland and the signatures of plate spreading". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 391: 106436. Bibcode:2020JVGR..39106436S. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2018.08.014.

- ^ Pedersen, G.B.M.; Belart, J.M.C.; Magnússon, E.; Vilmundardóttir, O.K.; Kizel, F.; Sigurmundsson, F.S.; Gísladóttir, G.; Benediktsson, J.A. (2018). "Hekla volcano, Iceland, in the 20th century: Lava volumes, production rates, and effusion rates". Geophysical Research Letters. 45 (4): 1805–1813. Bibcode:2018GeoRL..45.1805P. doi:10.1002/2017GL076887.

- ^ "Eyjafjallajökull". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2024-02-18.: Most Recent Bulletin Report: April 2011 (BGVN 36:04)

- ^ Guðmundsson, M.T.; Larsen, G (2019). "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes: Grímsvötn". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. Retrieved 18 February 2024.: Short Description

- ^ Larsen, G.; Guðmundsson, M.T. (2019). "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes:Bárðarbunga". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. Retrieved 28 January 2024.: Short Description

- ^ Einarsson, S. (2019). "Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes:Krýsuvík". Icelandic Meteorological Office, Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, Civil Protection Department of the National Commissioner of the Iceland Police. Retrieved 28 January 2024.: Detailed Description

- ^ Sigurdur Þórarinsson (1967). "The eruption of Hekla in historical times. Vol. I: The eruption of Hekla 1947–48". Soc. Sci. Islandica. 38: 1–183.

- ^ a b c Thordarson, T.; Self, S. (2003). "Atmospheric and environmental effects of the 1783–1784 Laki eruption: A review and reassessment". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 108 (D1): 4011. Bibcode:2003JGRD..108.4011T. doi:10.1029/2001JD002042. hdl:20.500.11820/17d8aae9-d2bf-4120-b61a-31c6966a7e24.: 4. Volcanic Pollution From Laki and Its Effects on the Environment

- ^ Thordarson, T.; Self, S. (2003). "Atmospheric and environmental effects of the 1783–1784 Laki eruption: A review and reassessment". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 108 (D1): 4011. Bibcode:2003JGRD..108.4011T. doi:10.1029/2001JD002042. hdl:20.500.11820/17d8aae9-d2bf-4120-b61a-31c6966a7e24.: 2.2. Eruption History

- ^ "The Most Infamous Eruptions in Icelandic History". guidetoiceland.is. Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- ^ Williams, Richard S. Jr.; James G. Moore (1983). "Man Against Volcano: The Eruption on Heimaey, Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland (2nd Edition)" (PDF). USGS. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ Bye, Bente Lilja (27 May 2011). "Volcanic eruptions: Science and Risk Management". Science 2.0. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Eyjafjallajökull. Eruptive History. Global Volcanism Program. Accessed 19 August 2020.

- ^ Katla. Detailed description. In: Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes. Accessed 19 August 2020

- ^ David Learmount (26 May 2011). "European proceedures (sic) cope with new ash cloud". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ^ "Bardarbunga". www.volcanodiscovery.com. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ^ a b Gudmundsson, Magnús T.; Jónsdóttir, Kristín; Hooper, Andrew; Holohan, Eoghan P.; Halldórsson, Sæmundur A.; Ófeigsson, Benedikt G.; Cesca, Simone; Vogfjörd, Kristín S.; Sigmundsson, Freysteinn (2016-07-15). "Gradual caldera collapse at Bárdarbunga volcano, Iceland, regulated by lateral magma outflow" (PDF). Science. 353 (6296): aaf8988. doi:10.1126/science.aaf8988. hdl:10447/227125. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27418515. S2CID 206650214.

- ^ Hudson, T. S.; White, R. S.; Greenfield, T.; Ágústsdóttir, T.; Brisbourne, A.; Green, R. G. (2017-09-16). "Deep crustal melt plumbing of Bárðarbunga volcano, Iceland" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 44 (17): 2017GL074749. Bibcode:2017GeoRL..44.8785H. doi:10.1002/2017gl074749. ISSN 1944-8007. S2CID 134072252.

- ^ "Ljós norðan jökuls: Töldu annað gos hafið". www.ruv.is/. RÚV. 31 August 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ See e.g. http://earthice.hi.is/bardarbunga_2014 Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland:Bardarbunga 2014

- ^ See also Icelandic media RÚV: http://www.ruv.is/frett/seismic-activity-still-strong Received Sept. 24, 2014

- ^ Boichu, M.; Chiapello, I.; Brogniez, C.; Péré, J.-C.; Thieuleux, F.; Torres, B.; Blarel, L.; Mortier, A.; Podvin, T. (2016-08-31). "Current challenges in modelling far-range air pollution induced by the 2014–2015 Bárðarbunga fissure eruption (Iceland)". Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16 (17): 10831–10845. Bibcode:2016ACP....1610831B. doi:10.5194/acp-16-10831-2016. ISSN 1680-7324.

- ^ Bindeman, I. N.; Deegan, F. M.; Troll, V. R.; Thordarson, T.; Höskuldsson, Á; Moreland, W. M.; Zorn, E. U.; Shevchenko, A. V.; Walter, T. R. (2022-06-29). "Diverse mantle components with invariant oxygen isotopes in the 2021 Fagradalsfjall eruption, Iceland". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 3737. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.3737B. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31348-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9243117. PMID 35768436.

- ^ Icelandic Media RÚV: https://www.ruv.is/frett/2021/03/19/eldgos-hafid-vid-fagradalsfjall. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ "Volcano near Iceland's main airport erupts again after series of earthquakes - CBS News". www.cbsnews.com. 2022-08-03. Retrieved 2023-12-19.

- ^ "Latest news on the volcanic eruption on the Reykjanes Peninula [sic]". Icelandic Meteorological office. 2023-07-10. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

- ^ "Continued likelihood of an eruption at the Sundhnúksgígar crater row". Icelandic Meteorological office. 2024-01-12. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

- ^ "Iceland volcano:Three Grindavik homes burn but lava defences save rest of town". The Independent. 2024-01-15. Retrieved 2024-01-15.

Non-English references

edit- ^ a b Lidén, Eva (1994). "Geologi-så bildades Island". Kall ökensand och varma källor. En bok om Island (in Swedish). Båstad: Föreningen Natur och Samhälle i Norden. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-91-85586-07-3.

External links

edit- Photos of the Grímsvötn (2004) and Eyjafjallajökull (2010) eruptions (Fred Kamphues)

- Map: active volcanoes of the world

- Icelandic Video Archive

- Volcano Discovery: Iceland

- List of volcanic eruptions in Iceland since 1900, Icelandic Met Office