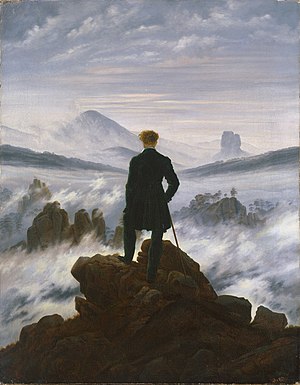

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog[a] is a painting by German Romanticist artist Caspar David Friedrich made in 1818.[2] It depicts a man standing upon a rocky precipice with his back to the viewer; he is gazing out on a landscape covered in a thick sea of fog through which other ridges, trees, and mountains pierce, which stretches out into the distance indefinitely.

| Wanderer above the Sea of Fog | |

|---|---|

| German: Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer | |

| |

| Artist | Caspar David Friedrich |

| Year | c. 1818 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 94.8 cm × 74.8 cm (37.3 in × 29.4 in) |

| Location | Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg |

It has been considered one of the masterpieces of the Romantic movement and one of its most representative works. The painting has been interpreted as an emblem of self-reflection or contemplation of life's path, and the landscape is considered to evoke the sublime. Friedrich was a common user of Rückenfigur (German: Rear-facing figure) in his paintings; Wanderer above the Sea of Fog is perhaps the most famous Rückenfigur in art due to the subject's prominence. The painting has also been interpreted as an expression of Friedrich's German liberal and nationalist feeling.

While Friedrich was respected in German and Russian circles, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog and Friedrich's work in general were not immediately regarded as masterpieces. Friedrich's reputation improved in the early 20th century, and in particular during the 1970s; Wanderer became particularly popular, appearing as an example of "popular art" as well as high culture on books and other works. The provenance of the artwork after its creation is unknown, but by 1939, it was on display in the gallery of Wilhelm August Luz in Berlin, and in 1970, it was acquired by the Hamburger Kunsthalle in Hamburg, Germany, where it has been displayed ever since.

Description

editIn the foreground, a man stands upon a rocky precipice with his back to the viewer. He is wrapped in a dark green overcoat, and grips a walking stick in his right hand.[3] His hair caught in a wind, the wanderer gazes out on a landscape covered in a thick sea of fog. In the middle ground, several other ridges, perhaps not unlike the ones the wanderer himself stands upon, jut out from the mass.[4] Through the wreaths of fog, forests of trees can be perceived atop these escarpments. In the far distance, faded mountains rise in the left, gently leveling off into lowland plains in the right. Beyond here, the pervading fog stretches out indefinitely, eventually commingling with the horizon and becoming indistinguishable from the cloud-filled sky.[3]

The painting is composed of various elements from the Elbe Sandstone Mountains in Saxony and Bohemia, sketched in the field but in accordance with his usual practice, rearranged by Friedrich himself in the studio for the painting. In the background to the right is the Zirkelstein.[5] The mountain in the background to the left could be either the Rosenberg or the Kaltenberg. The group of rocks in front of it represent the Gamrig near Rathen. The rocks on which the traveller stands are a group on the Kaiserkrone.[6]

Creation and history

editThe date of creation of Wanderer is generally given as 1818, although some sources indicate 1817. The provenance of the painting in the 19th century is unclear, but it came to the ownership of the gallery of Wilhelm August Luz in Berlin in 1939. It was then apparently sold to Ernst Henke, a German lawyer, before returning to the Luz gallery. The painting bounced between private collections before being acquired by the Hamburger Kunsthalle (Hamburg Art Hall) in 1970, where it has been on display since.[7]

Notable events in Friedrich's life in 1817 and 1818 include him striking up a friendship with the scientist Carl Gustav Carus and the Norwegian painter Johan Christian Dahl in 1817, Friedrich marrying Caroline Brommer in January 1818, and the couple going on a honeymoon back to Friedrich's hometown of Greifswald for weeks after.[8]

Romanticism

editWanderer above the Sea of Fog is closely associated with Romanticism, a broad artistic and literary movement that emerged after the Age of Enlightenment.[9] While the identity of the man is uncertain, some have suggested it is a self-portrait of the artist himself, pointing to similarities in appearance, such as the red hair,[10] and for this reason the painting has been interpreted as an emblem of self-reflection or contemplation of life's path.[4][3] The landscape of Wanderer is considered to evoke the sublime, of greater mysteries and potential beyond the typical. Friedrich stated his ideas in regards to this, "The artist should paint not only what he has in front of him but also what he sees inside himself."[11] On mist, he wrote "When a region cloaks itself in mist, it appears larger and more sublime, elevating the imagination, and rousing the expectations like a veiled girl."[12]

Differences still exist between Friedrich and other Romanticists. Werner Hofmann wrote that Wanderer was more open-ended and questioning than typical Romantic works. He compares Friedrich's searching Wanderer who does not know the future with Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People, which is more certain about the course of action required, perhaps related to the differences in German and French nationalism of the era.[13]

Friedrich criticized other artists of his day[b] as painting overfilled "curiosity shops" that covered every part of the canvas with new features.[14] While Wanderer is detailed, it does not lose focus by including an array of geographic features, other people, or buildings; the work stays centered on the mountains and the mist, and lets the viewer's eye explore it at its own pace.

Rückenfigur and similar work

editTraditional art standards hold that if people are present in a scene, they are turned toward the viewer or in profile. Exceptions exist but are generally for minor characters in a crowded scene. While Friedrich was not the first artist to use a Rückenfigur, he used such figures turned away from the viewer considerably more frequently and persistently than other artists.[15] Friedrich's use of the Rückenfigur was generally considered to invite viewers "inside" the painting and encourage the viewer to consider the perspective from the depicted mysterious person whose face cannot be seen. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog is perhaps the most famous Rückenfigur in art due to the subject's prominence.[15] The figure changes the sense and focus of the painting. Helmut Börsch-Supan wrote that "It is harder to imagine this landscape without a figure than it is in any other painting."[16]

Other works of Friedrich's comparable to Wanderer with such a Rückenfigur motif include Woman at a Window, Two Men by the Sea at Moonrise, and Neubrandenburg.[5]

Wieland Schmied argues that Wanderer was a precursor to the surrealism of René Magritte; Friedrich included subtle incongruities in his work and seemingly impossible perspectives, as seen in Wanderer, and Magritte took such elements even further in his work.[17] The background of the picture seemingly plunges into the foreground, with the depth between them unclear.[18]

Political backdrop

editFriedrich was an outspoken supporter of German liberal and nationalist feeling. The old German princely states were disrupted and saw their authority compromised in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars of 1803–1815. German nationalists advocated the Unification of Germany and the abolition of the conservative German nobility and leadership of the German Confederation. One of the ways German liberals identified themselves and showed their support was by a fashion trend: Altdeutsche ("Old German") outfits, a restoration of an imagined heroic unified German past of the 1500s–1600s and the age of Martin Luther.[c] Nationalists such as Friedrich thus identified themselves with restoring a lost national greatness. The art historian Norbert Wolf, following Koerner and others, has stated that the figure in Wanderer above the Sea of Fog wears just such an Altdeutsches outfit, a political statement in the era when the painting was created.[19] Other scholars have described the figure's clothing as a Jäger infantry uniform.[15]

A matter less clear is how Friedrich's Lutheranism affected Wanderer, if at all. Friedrich's religious side is seen in other paintings of his, such as the 1810 painting Cross in the Mountains, which fit a humble sort of Christianity that found beauty in nature. This corresponds with Luther's writing that all the great cathedrals and pompous buildings of the Catholic Church of his era could be torn down with little loss. To Friedrich's interpretation of Lutheranism, true religion was found in nature, simplicity, and individual people, all elements of Wanderer.[20] Another potential link was how Friedrich met and befriended the scientist and fellow painter Carl Gustav Carus in 1817 just before he would have been preparing and painting Wanderer. Art historian Joseph Koerner notes that Carus wrote on a particular verse in the Luther Bible: Luther translated the account of God's creation of Earth in the Book of Genesis 2:6 as Aber ein Nebel ging auf von der Erde und feuchtete alles Land (English: A fog arose from the Earth and moistened the entire land).[21] Carus argued the fog was God's assistant in the Creation, turning barren mountains into verdant forests. Koerner hypothesizes that Carus and Friedrich could have discussed the matter in the course of their friendship. He sees that Wanderer could well be depicting a Creation-esque scene: the figure views a land of unknown possibility, hidden in the mist, emerging from the heart as an emanation from the "I".[15]

Mountain climbing

editRobert Macfarlane argues the painting had significant influence on how mountain climbing has been viewed in the Western world since the Romantic era, calling it the "archetypical image of the mountain-climbing visionary". He admires its power in representing the concept that standing on mountain tops is something to be admired, an idea which barely existed in earlier centuries.[22]

Reception

editWhile Friedrich was respected in German and Russian circles, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog and Friedrich's work in general were not immediately regarded as masterpieces. His fame waned as he grew older; he wrote that the art judges of his day did not appreciate winter landscapes and mist enough.[12] Friedrich's reputation improved in the early 20th century, and in particular during the 1970s. Wanderer became particularly popular: used as an inspiration for a variety of works since, and not merely known among art scholars. Wanderer has appeared on the cover of numerous books, T-shirts, CDs, coffee mugs, and so on, becoming a staple of "popular art" as well as high culture.[20] Werner Hofmann hypothesizes that the subject looking upon a canvas of open possibility, ready to make a choice and find what awaits him, appeals to modern viewers.[20]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Also translated as Wanderer above the Mist, Mountaineer in a Misty Landscape,[1] and other variants; Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer in German

- ^ Friedrich left the artists he criticized unnamed; Werner Hofmann suggests that he might have been attacking Joseph Anton Koch.[14]

- ^ Such alleged German unity in the 1500s was entirely imaginary, to be clear.[15]

References

edit- ^ Arts Council of Great Britain (1959). The romantic movement. Fifth exhibition to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Council of Europe, 10 July to 27 September 1959, the Tate Gallery and the Arts Council Gallery, London. Arts Council of Great Britain.

- ^ Exhibition Catalogue: Caspar David Friedrich. Die Underling der Romantic in Essen ind Hamburg, Firmer Verlag, München (December 2006), page 267

- ^ a b c Gaddis, John Lewis (2004). "The Landscape of History". The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-19-517157-8.

- ^ a b Gorra, Michael Edward (2004). The Bells in Their Silence: Travels Through Germany. Princeton University Press. pp. 11-12. ISBN 0-691-11765-9. JSTOR j.ctt7sr5d.

- ^ a b Grave, Johannes (2012). Caspar David Friedrich. Translated by Elliot, Fiona. Prestel. pp. 202–206. ISBN 978-3-7913-4628-1.

- ^ Hoch, Karl-Ludwig (1987). Caspar David Friedrich und die böhmischen Berge. Dresden: Kohlhammer Verlag. p. 215. ISBN 978-3-17-009406-2.

- ^ Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer, UM 1817, Hamburger Kunsthalle

- ^ Hofmann 2000, p. 286

- ^ Gunderson, Jessica (2008). Romanticism. The Creative Company. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-58341-613-6.

- ^ "A Closer Look at Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich". drawpaintacademy.com. 10 February 2020.

- ^ "Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, Caspar David Friedrich (Ca. 1817)." Scholastic Art

- ^ a b Hofmann 2000, p. 33

- ^ Hofmann 2000, pp. 10–12

- ^ a b Hofmann 2000, pp. 258–260

- ^ a b c d e Koerner, Joseph Leo (1995) [1990]. Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 162–163; 179–194; 242-244. ISBN 0-300-06547-7.

- ^ Borsch-Supan 2005, p. 116. Cited in Grave 2012, p. 203.

- ^ Schmied, Wieland (1995) [1992]. Caspar David Friedrich. Translated by Stockman, Russel. New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8109-3327-9.

- ^ Hofmann 2000, p. 20

- ^ Wolf, Norbert. Caspar David Friedrich: The Painter of Stillness. 2012. pp. 56-57

- ^ a b c Hofmann, Werner (2000). Caspar David Friedrich. Translated by Whittall, Mary. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 9–13, 245–251, 260. ISBN 0-500-09295-8.

- ^ Genesis 2:6, Luther Bible.

- ^ Macfarlane, Robert (2003). Mountains of the Mind: A History of a Fascination. Granta Books. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-84708-039-4.

External links

edit- Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer, UM 1817, official page by the Hamburger Kunsthalle

- Sketches for the painting (in German)

- Idrobo, Carlos (November 2012). "He Who Is Leaving ... The Figure of the Wanderer in Nietzsche's Also sprach Zarathustra and Caspar David Friedrich's Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer". Nietzsche-Studien. 41 (1): 78–103. doi:10.1515/niet.2012.41.1.78. S2CID 155017448. (Online) (Print).

- Media related to Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer (Caspar David Friedrich) at Wikimedia Commons