Wannaganosuchus (meaning "Wannagan crocodile", in reference to the Wannagan Creek site where it was discovered) is an extinct genus of small alligatorid crocodilian. It was found in Late Paleocene-age rocks of Billings County, North Dakota, United States.

| Wannaganosuchus Temporal range: Late Paleocene,

| |

|---|---|

| |

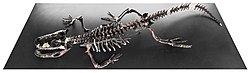

| Fossil of Wannaganosuchus brachymanus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Archosauriformes |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Alligatoridae |

| Subfamily: | Alligatorinae |

| Genus: | †Wannaganosuchus Erickson, 1982 |

| Type species | |

| †Wannaganosuchus brachymanus Erickson, 1982

| |

History and description

editWannaganosuchus is based on SMM P76.28.247, a mostly complete skull and postcranial skeleton missing some vertebrae, coracoids, part of the feet, ribs, and other pieces. A few small bony scutes are also assigned to the genus, but not to the type specimen. SMM P76.28.247 was found semi-articulated in the lower part of the Bullion Creek Formation, near the base of a lignitic clay layer deposited in a marsh setting on a floodplain. Wannaganosuchus was named in 1982 by Bruce R. Erickson. The type species is W. brachymanus; the specific name means "short forefoot".[2]

The skull of SMM P76.28.247 was low, without elevated rims over the eyes, and was 159 millimetres (6.3 in) long. The snout was short and pointed compared to Cretaceous alligatorids. Its premaxillae (the bones of the tip of the snout) had five teeth each, while the maxillae (main tooth-bearing bones of the upper jaw) had thirteen teeth each, with the fourth being the largest and the last three having broad flattened crowns. The lower jaws had twenty teeth on each side, and like the upper jaws, the last five had broad crushing crowns. The forelimbs were short (hence the specific name), and the hindlimbs were long in comparison. The scutes were extensive. Most of the scutes were keeled, but did not have spikes.[2]

Erickson regarded Wannaganosuchus as a generalized early alligatorid closer to the line leading to modern alligatorids than other more specialized early alligatorids.[2] It may be the same as Allognathosuchus.[3]

Paleoecology and paleobiology

editWannaganosuchus was found in a layer with abundant plant fossils suggesting the presence of a swamp forest in the area; taxodioid logs are common. The deposit was formed under 2 to 3 metres (6.6 to 9.8 ft) of water, and grades into a shoreline deposit about 20 metres (66 ft) away. Lilies and water ferns grew along the shore and were shaded by cypress trees.[2]

SMM P76.28.247 was found in direct association with skeletons of Borealosuchus formidabilis and the long-snouted champsosaur Champsosaurus. These three taxa probably occupied different ecological niches based on size and morphology. Wannaganosuchus was a small alligatorid, only about 1.00 metre (3.28 ft) long as an adult, much smaller than its more abundant distant relative from the same quarry, Borealosuchus (roughly 4 metres (13 ft) long). Borealosuchus would have dominated the beach zone, while Champsosaurus is interpreted as a piscivore that swam near the bottom. Wannaganosuchus is thought to have lived like the modern caiman Paleosuchus, preferring seclusion. It may have floated among clumps of water plants. The structure of the arms, legs, and tail suggest that it was more aquatic than terrestrial. The mix of tooth shapes indicate it could eat a variety of foods.[2]

Phylogeny

editRecent studies have consistently resolved Wannaganosuchus as a member of Alligatorinae, although its relative placement is disputed, as shown by the cladograms below.[4][5][6]

Cladogram from 2018 Bona et al. study:[4]

| Alligatorinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cladogram from 2019 Massonne et al. study:[5]

| Alligatorinae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cladogram from 2020 Cossette & Brochu study:[6]

| Alligatorinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

edit- ^ Rio, Jonathan P.; Mannion, Philip D. (6 September 2021). "Phylogenetic analysis of a new morphological dataset elucidates the evolutionary history of Crocodylia and resolves the long-standing gharial problem". PeerJ. 9: e12094. doi:10.7717/peerj.12094. PMC 8428266. PMID 34567843.

- ^ a b c d e Erickson, Bruce R. (1982). "Wannaganosuchus, a new alligator from the Paleocene of North America". Journal of Paleontology. 56 (2): 492–506.

- ^ Sullivan, R.M.; Lucas, S.G.; Tsentas, C. (1988). "Navajosuchus is Allognathosuchus". Journal of Herpetology. 22 (1). Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 22, No. 1: 121–125. doi:10.2307/1564367. JSTOR 1564367.

- ^ a b Paula Bona; Martín D. Ezcurra; Francisco Barrios; María V. Fernandez Blanco (2018). "A new Palaeocene crocodylian from southern Argentina sheds light on the early history of caimanines". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 285 (1885): 20180843. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.0843. PMC 6125902. PMID 30135152.

- ^ a b Tobias Massonne; Davit Vasilyan; Márton Rabi; Madelaine Böhme (2019). "A new alligatoroid from the Eocene of Vietnam highlights an extinct Asian clade independent from extant Alligator sinensis". PeerJ. 7: e7562. doi:10.7717/peerj.7562. PMC 6839522. PMID 31720094.

- ^ a b Adam P. Cossette; Christopher A. Brochu (2020). "A systematic review of the giant alligatoroid Deinosuchus from the Campanian of North America and its implications for the relationships at the root of Crocodylia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (1): e1767638. Bibcode:2020JVPal..40E7638C. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1767638.