Warren Livingston Cromartie (born September 29, 1953) is an American former professional baseball player best remembered for his early career with the Montreal Expos. He and fellow young outfielders Ellis Valentine and Andre Dawson were the talk of Major League Baseball (MLB) when they came up together with the Expos in the late seventies.[1] Nicknamed "Cro" and "the Black Samurai" in Japan, he was very popular with the fans in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. He won the 1989 Nippon Professional Baseball Most Valuable Player Award during his career playing baseball in Japan for the Yomiuri Giants.

| Warren Cromartie | |

|---|---|

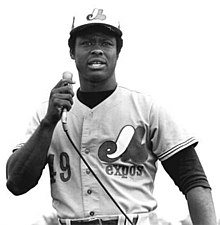

Cromartie with the Montreal Expos in 1980 | |

| Outfielder / First baseman | |

| Born: September 29, 1953 Miami Beach, Florida, U.S. | |

Batted: Left Threw: Left | |

| Professional debut | |

| MLB: September 6, 1974, for the Montreal Expos | |

| NPB: April 6, 1984, for the Yomiuri Giants | |

| Last appearance | |

| NPB: June 2, 1990, for the Yomiuri Giants | |

| MLB: September 15, 1991, for the Kansas City Royals | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .281 |

| Home run | 61 |

| Runs batted in | 391 |

| NPB statistics | |

| Batting average | .321 |

| Home runs | 171 |

| Runs batted in | 558 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Early years

editCromartie was the only child of Marjorie and Leroy Cromartie.[2] Leroy played quarterback at Florida A&M College, and led his team to Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference championships in 1944 and 1945. Having also played basketball and baseball in high school, he left FAMC to play semi-pro baseball with the Miami Giants, which led to a brief stint as a second baseman with the Cincinnati/Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro leagues. After that, Leroy returned to FAMC and led the Rattlers to another SIAC championship in 1947 and a national championship in 1950.[3]

Upon graduation from Miami Jackson High School in 1971, Warren Cromartie was drafted by the Chicago White Sox in the seventh round of that year's draft, but opted to instead attend Miami Dade College. Following this, he was drafted by three other teams (the Minnesota Twins in the third round of the January 1972 secondary draft, the San Diego Padres in the first round of June 1972 secondary draft, and the Oakland Athletics in the January 1973 secondary draft) but did not sign with any of the clubs. Finally, when the Expos selected him in the first round of the June 1973 secondary draft, he signed. Cromartie batted .336 with 13 home runs, 61 runs batted in and 30 stolen bases in his first professional season (1974) with the Quebec Carnavals. This performance earned him a September call-up to the major leagues all the way from double A. He went 3-for-17 with three walks during his short stint with the Expos.

He went into Spring training 1975 competing for the open right field job, but was sent to "Expoville," the Expos' minor league complex in Daytona Beach, for reassignment to the triple A Memphis Blues in late March.[4] After a disappointing 1975 season in Memphis, he rebounded nicely in 1976 to bat .337 for the American Association's Denver Bears, and receive a call up to the Expos in mid-August. He spent the rest of the season pretty much platooning with Ellis Valentine in right field, batting .210 with two RBIs.

Montreal Expos

editThe Expos' young outfield

editBoth Cromartie and Valentine won starting jobs in Montreal's outfield out of Spring training 1977, with Cromartie shifting to left field. Joining them in the Expos' outfield would be 22-year-old center fielder Andre Dawson. Their youth, speed and talent soon made them the talk of the baseball world.[1] Cromartie hit his first major league home run against the New York Mets' Nino Espinosa on July 2.[5] Usually batting either second or fifth in the Expos' line-up, he spent most of the season with a batting average over .300, but cooled off to .282 with five home runs and 50 RBIs by the end of the season.

Cromartie was considered something of a defensive liability his rookie season,[1] and worked on his defense during the off season. As a result, he led National League left fielders in many defensive categories in 1978. He, Dawson and Valentine each led their respective positions in outfield assists to give the Expos the unquestionable top defensive outfield in the major leagues. With his bat, he got off to a slow start in 1978. He ended April with just a .193 batting average and two RBIs. From there, he batted .307 over the rest of the season to finish just below .300 (.297, which was tops on the team). His first major league grand slam was a walk off against the Atlanta Braves on July 19.[6]

After going 0-for-five in the 1979 season opener with the Pittsburgh Pirates,[7] Cromartie embarked upon a 19-game hitting streak, the longest of his career.[8] His hot start helped propel the Expos into their first real pennant race in franchise history. The Expos battled the Pirates and Philadelphia Phillies for first place in the National League East throughout the season, with their lead in the division peaking at 6.5 games on July 2. They would eventually win a franchise-best 95 games but still finished second to the World Series-winning Pirates by two games. For his part, Cromartie batted .275 with eight home runs and a career-best 84 runs scored.

Shift to first base

editCromartie had played some first base in the minor leagues, and was shifted there for the 1980 season[9] after the Expos acquired outfielder Ron LeFlore from the Detroit Tigers at the Winter meetings.[10] He had difficulty fielding his new position, committing a league leading 14 errors at first; however, he had one of his best seasons with his bat. He batted .288, and putting up career highs in home runs (14) and RBIs (70).

Perhaps the most memorable moment of Cromartie's 1980 season was a Fourth of July doubleheader with the New York Mets. He committed two of five errors by the Expos in the sloppily played first game loss (the Mets also committed three).[11] After committing a third error in the second game, he also hit a two-run home run that carried the Expos to a 6–5 victory.[12]

The Expos again found themselves in a pennant race in 1980 despite key injuries to LeFlore, Valentine, Larry Parrish and pitcher Bill Lee, among others (Cromartie was the only player on the team who managed to play a full 162 game schedule). Their season came down to a season ending three game set with the Philadelphia Phillies at Olympic Stadium; the Phillies won two out of three to win the division, and head to the post-season (Cromartie went hitless in eleven at bats).[13]

The Expos were uninterested in re-signing LeFlore for the 1981 season, and allowed him to depart via free agency.[14] Rather than shifting Cromartie back to left field, he remained at first with rookie Tim Raines given the starting job in left. When Valentine was dealt to the New York Mets shortly before the players strike,[15] Cromartie shifted to right field with Willie Montañez assuming first base duties. With Montañez producing just a .177 batting average, he was dealt to the Pirates for fellow first baseman John Milner on August 20.[16] Cromartie was eventually shifted back to first base in September with Tim Wallach taking over in right field.

Post season

editAs a result of the players strike, the owners decided to split the 1981 season into two halves, with the first-place teams from each half in each division meeting in a best-of-five divisional playoff series (the first time that Major League Baseball used a split-season format since 1892). Cromartie batted .328 with three home runs, 18 RBIs and 24 runs scored in the second half to help the Expos win the NL East by half a game over the St. Louis Cardinals.

After two consecutive near misses, Cromartie and most of his teammates were reaching the post season for the first time in their careers. Cromartie went two-for-four with an RBI double off Steve Carlton in the opening game of the 1981 National League Division Series to help bring his club to a 3–1 victory over the future Hall of Famer.[17] They defeated the Phillies in five games, but lost to the Los Angeles Dodgers in a five-game National League Championship Series. Cromartie was in the on-deck circle when the Dodgers recorded the final out of the 1981 National League Championship Series.

Right field

editJust as the 1982 season was set to begin, the Expos acquired first baseman Al Oliver from the Texas Rangers for third baseman Larry Parrish and first baseman Dave Hostetler. With this acquisition, Cromartie was shifted to right field.[18] Cromartie was batting just .211 when he belted a walk-off home run off Cardinals closer Bruce Sutter on June 7.[19] From there, he brought his average up to a far more respectable .250 with decent power numbers (10 home runs, 49 RBIs); however, the Expos still elected to acquire right fielder Joel Youngblood from the New York Mets for a player to be named later on August 4.[20]

Youngblood cost Cromartie playing time when he first arrived in Montreal. The .192 batting average he put up in his first month with his new club, however, prompted manager Jim Fanning to give the job back to Cromartie full-time. For the season, Cromartie batted .254 with 62 RBIs and matched his career high with 14 home runs.

Youngblood's tenure with the Expos lasted just one season, as did Fanning's. With the arrival of new manager Bill Virdon in 1983, Cromartie found himself in a battle with Terry Francona, who was coming back from a knee injury, for the right field job the following spring.[21] Cromartie won the job, but still saw limited action in 1983. On July 15, Cromartie tipped a food table in the Expos clubhouse following a 9–3 loss to the Atlanta Braves. Virdon suspended him three games for his temper tantrum.[22] Back problems limited him to nine plate appearances in the Expos' final 26 games.

Yomiuri Giants

editCromartie became a free agent at the end of the season. After receiving some interest from the San Francisco Giants, he instructed agent Cookie Lazarus to send out feelers in Japan. He ended up signing with the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants of Nippon Professional Baseball on December 28, 1983. At 30 years old, Cromartie became the first, and perhaps the most prominent, American player still in his prime to sign with a Japanese baseball team.[23]

Upon his arrival in Japan, his manager, legendary Japanese slugger Sadaharu Oh, noticed a hitch in Cromartie's swing. He had Cromartie take batting practice with a book under his elbow to correct it.[24] He had ten game-winning RBIs in his first season,[25] and belted over thirty home runs in each of his first three seasons. During Cromartie's second season in Japan, his second son, Cody Oh Cromartie, was born. His middle name is in honor of Sadaharu Oh.[26]

The low point of Cromartie's career in Japan came in June 1987. The Central League suspended Cromartie for seven days and fined him $2143 for inciting a brawl with Masami Miyashita, a Chunichi Dragons pitcher who hit him in the back. The next time the Giants played in Nagoya, over 200 security guards were employed to protect Cromartie from the angry fans.[24]

A broken thumb also limited him to just 49 games in 1988.[27] He appeared to be on his way to being Wally Pipped when his replacement, Ming-Tsu Lu, clubbed four home runs in his first five games. Lu was Taiwanese, and NPB has a "gaijin waku," or a limit of two foreign born players per team. Cromartie's former teammate with the Expos, pitcher Bill Gullickson, was also a member of the Giants.[28] Given the salaries of Cromartie and Gullickson, Lu ended up being the odd man out.[27] He even intended to leave after that season after Oh was let go from his managerial position that year, but was convinced by second stint manager Motoshi Fujita to stay to help the Giants christen the then-newly constructed Tokyo Dome.

In 1989, Cromartie batted .378 with 15 home runs and 78 RBIs to be named MVP of the Central League, and lead his team to the Japan Series championship. In the deciding game of the series with the Kintetsu Buffaloes, who had the Pacific League MVP, fellow foreigner Ralph Bryant, Cromartie doubled in the fourth inning to ignite a three-run rally and homered in the seventh.[29] He originally intended to retire at the end of the season,[27] but his success prompted him to spend one more season with the Giants.

Kansas City Royals

editCromartie was invited to Spring training with the Kansas City Royals in 1991,[30] and earned a one-year deal at the league minimum to serve as a left-handed bat off the bench. In limited duty, Cromartie batted .313 with one home run and 20 RBIs. He retired during the season with 20 games still remaining on the schedule.[31]

MLB stats

edit| Games | PA | AB | Runs | Hits | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BB | SO | Avg. | OBP | Slg. | OPS | Fld% |

| 1107 | 4318 | 3927 | 459 | 1104 | 229 | 32 | 61 | 391 | 50 | 325 | 403 | .281 | .336 | .402 | .739 | .986 |

In seven seasons in Japan, Cromartie batted over.300 five times. All told, he compiled a .321 batting average with 171 home runs and 558 RBIs for the Yomiuri Giants. He led the Giants three times in RBIs, twice in home runs and twice in batting.[32]

Climb

editCromartie is an accomplished drummer, and has jammed with Canadian rock band Rush.[23] A blueprint for the fictional "Warren Cromartie Secondary School" appears on the back cover of Rush's 1982 release, Signals, and Cromartie is thanked in the album's liner notes.

While in Japan, Cromartie formed an AOR band called Climb with David Rosenthal of Rainbow. Rush lead singer Geddy Lee appears on the track "Who's Missin' Who" from their 1988 release, Take A Chance.[33] Mitch Malloy and Foreigner's Lou Gramm also make guest appearances on the album.

Broadcasting

editRight as his only season in Kansas City was set to start, his autobiography (co-written with Robert Whiting) detailing his playing days in Japan, Slugging It Out in Japan: An American Major-Leaguer in the Tokyo Outfield, hit bookstores.

Cromartie began doing Florida Marlins pre-game shows for WQAM radio in 1997, and remained a broadcaster with the Marlins in one form or another through 2002. He served as the television color commentator for the Montreal Expos in the team's final year of existence (2004). He currently hosts a radio show on WAXY 790 AM in Miami, Florida. "Talking Hardball with The Cro" currently airs on Saturday during baseball season.[34] He has his own segment on the TSN 690 in Montreal, and regularly airs at 4:00 PM Eastern on weekdays with Mitch Melnick.

In 2005, Cromartie sued the makers of a film based on the manga/anime series Cromartie High School in Japanese court. The series does not feature Cromartie himself but does depict students who "smoke, fight with students from other schools and are depicted as ruffians" which he says defames his character as the school shares his name.

Coaching

editThe Miami native held his first baseball camp at Miami-Dade Community College's North Campus in 1994. He was the manager of the Japan Samurai Bears, an all-Japanese team in the independent U.S. Golden Baseball League during the league's only season (2005). Danny Gold and Matthew Asner of Mod 3 Productions filmed a documentary of the club entitled Season of the Samurai. It aired on the MLB Network in 2010.[35]

He formed the Montreal Baseball Project in 2012 to launch a feasibility study into bringing Major League Baseball back to Montreal.[36]

Other ventures

editHe, Andre Dawson and Cecil Fielder of the Detroit Tigers (whom Cromartie met while the two played in Japan) teamed up to form "Sports Dent" in 1993. The company produced baseball themed dental hygiene products, including a baseball bat shaped toothbrush, a toothbrush holder that plays Take Me Out to the Ballgame, a dental floss dispenser shaped like home plate and mock baseball cards to record one's "Runs brushed in."[37]

In 2007, he made his professional wrestling debut at an event called "Hustle Aid" to benefit leukemia research. He and Ryoji Sai took on Tiger Jeet Singh and An Joenosuke in a tag team match at Tokyo's Saitama Arena.[38] As Singh is known for walking around with a sword in his mouth, Cromartie showed up with a baseball bat, and wearing a baseball uniform with the words "Samurai Man" across his chest and the number 49 from his playing days on the back. The match ended with Cromartie pinning An Joenosuke for the victory.[39]

References

edit- ^ a b c Bob Dunn (August 8, 1977). "A Bargain, And Bye-bye Basement". Sports Illustrated.

- ^ Cesar Brioso (September 15, 2000). "Negro Leaguer Cromartie Dies". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- ^ "Leroy Cromartie". Baseball in Living Color: Negro Leagues Baseball History.

- ^ Brad Willson (March 30, 1975). "Bailey Sidelined With Broken Bone". Daytona Beach Sunday News-Journal. p. 3C.

- ^ "Montreal Expos 4, New York Mets 3". Baseball-Reference.com. July 2, 1977.

- ^ "It Took a Bunt, but Rose Kept Streak Alive". Observer–Reporter. July 20, 1978.

- ^ "Montreal Expos 3, Pittsburgh Pirates 2". Baseball-Reference.com. April 6, 1979.

- ^ Norm King. "Warren Cromartie". Society for American Baseball Research.

- ^ Pat Livingston (March 30, 1980). "How Do Expos Spell Trouble? L-e-F-l-o-r-e". Pittsburgh Press.

- ^ Joe Potter (December 11, 1979). "Santa Campbell Gives Expos Christmas Gift". Virgin Islands Daily News.

- ^ "New York Mets 9, Montreal Expos 5". Baseball-Reference.com. July 4, 1980.

- ^ "Mets and Expos End Long Day with Fight". The Day (New London). July 5, 1980.

- ^ "Dodgers Stay Alive, Expos Bow to Phillies". Leader-Post. October 6, 1980.

- ^ "LeFlore Not Wanted By Expos". The StarPhoenix. November 29, 1980.

- ^ "Expos Send Mets an Early Valentine". Leader-Post. May 30, 1981.

- ^ Michael Farber (August 21, 1981). "Expos Get Milner as Montanez Dealt". The Gazette (Montreal).

- ^ "1981 National League Division Series, Game One". Baseball-Reference.com. October 7, 1981.

- ^ Bob Elliott (sportswriter) (April 1, 1982). "Oliver 'Will Make the Difference'". Ottawa Citizen.

- ^ "Montreal Expos 3, St. Louis Cardinals 2". Baseball-Reference.com. June 7, 1982.

- ^ Ralph Bernstein (August 5, 1982). "Joel Youngblood Makes History With Mets, Expos". Portsmouth Daily Times.

- ^ Vin Mannix (March 6, 1983). "Cromartie & Francona". Boca Raton News.

- ^ Brian Kappler (July 21, 1983). "Expos Thump Reds Ace for Victory". Montreal Gazette.

- ^ a b "Disgusted Cromartie Off to Japan". Montreal Gazette. December 29, 1983.

- ^ a b Robert Whiting (August 21, 1989). "The Master Of Besaboru". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- ^ Dave Komosky (September 22, 1984). "Button Up, Mr. Sather". The Phoenix.

- ^ Cromartie, Warren (August 1, 2014). "5 for Friday: Warren Cromartie, Montreal's next best baseball savior" (Interview). Interviewed by Erik Malinowski. Fox Sports. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ a b c Eric Talmadge (May 24, 1989). "Cromartie Likes Japan's Pitching". Bangor Daily News.

- ^ Eric Talmadge (July 3, 1988). "Japanese Baseball May Change 'Foreigners' Rule". The Daily Union.

- ^ "Yomiuri Wins Japan Series Title". Ocala Star-Banner. October 30, 1989.

- ^ Ken Willis (March 25, 1991). "After 15 Seasons, Cromartie Brings Bat Home to America". The News Journal.

- ^ "Cromartie Career Ends at Age 37". Lawrence Journal-World. September 16, 1991.

- ^ "Past Yomiuri Giants Stars". The Yakult Swallows Home Plate.

- ^ "Rush Guest Appearances". Power Windows.

- ^ "Talkin' Hardball With The Cro". Sportstalk 790 AM/104.3 FM.

- ^ "Former MLBer Warren Cromartie manages all-Japanese baseball team in Season of the Samurai". MLB.com. June 24, 2010.

- ^ Bill Beacon (March 20, 2013). "Ex-Expo Warren Cromartie Heads Group Studying Viability of Returning Baseball to Montreal". The Vancouver Sun.

- ^ "Names in the News". The Daily Sentinel. August 10, 1993.

- ^ "Ex-Expos outfielder Cromartie Will Step into the Ring". ESPN. June 12, 2007.

- ^ Alastair Himmer (June 18, 2007). "Former MLB Player Roughs Up Angry Tiger". Reuters.

Bibliography

edit- Cromartie, Warren and Whiting, Robert. Slugging It Out in Japan: An American Major-Leaguer in the Tokyo Outfield, Kodansha, 1991.

External links

edit- Career statistics from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Warren Cromartie Biography at Baseball Biography

- Venezuelan Professional Baseball League batting statistics

- Warren Cromartie Baseball School

- IMDB Reference