Wealhtheow (also rendered Wealhþēow or Wealthow; Old English: Ƿealhþēoƿ [ˈwæɑɫxθeːow]) is a queen of the Danes in the Old English poem, Beowulf, first introduced in line 612.

Character overview

editWealhtheow is of the Wulfing clan,[1] Queen of the Danes. She is married to Hrothgar (Hrōðgār), the Danish king and is the mother of sons, Hreðric and Hroðmund, and a daughter Freawaru.

In her marriage to Hrothgar she is described as friðusibb folca[2] (l. 2017), 'the kindred pledge of peace between peoples', signifying interdynastic allegiance between Wulfing and Scylding achieved with her marriage to Hrothgar. She is both 'Lady of the Helmings' (l. 620) (by descent, of the Wulfing clan of Helm) and 'Lady of the Scyldings' (l. 1168), by marriage and maternity.

Two northern sources associate the wife of Hrothgar with England. The Skjöldunga saga, in Arngrímur Jónsson's abstract, chapter 3, tells that Hrothgar (Roas) married the daughter of an English king. The Hrolfs saga kraka, chapter 5, tells that Hrothgar (Hróarr) married Ögn who was the daughter of a king of Northumbria (Norðhymbraland) called Norðri.

The argument was advanced in 1897 that the Wulfing name may have been synonymous with the East Anglian Wuffing dynasty, and the family name Helmingas with the place-names 'Helmingham' in Norfolk and Suffolk, both of which lie in areas of 5th–6th century migrant occupation.[3] Although the theory was not favoured by some,[4] it has more recently resurfaced in a discussion of the identity of Hroðmund.[5]

Name

editThe name Wealhtheow is unique to Beowulf. Like most Old English names, the name Wealhtheow is transparently recognisable as a compound of two nouns drawn from everyday vocabulary, in this case wealh (which in early Old English meant "Roman, Celtic-speaker" but whose meaning changed during the Old English period to mean "Briton", then "enslaved Briton", and then "slave") and þēow (whose central meaning was "slave").[6] Whether this name was thought by the poet(s) or audiences of Beowulf to have any literary meaning is disputed.[6] Since it can be translated as "foreigner-slave" or the like, the name Wealhtheow has often been thought to indicate that the character Wealhtheow came to marry Hrothgar by being captured from another people.[7] Yet Old English names do not normally seem to have been understood as lexically meaningful compound nouns.[6]

In 1935, E. V. Gordon argued that the form of Wealhtheow's name in the Beowulf-manuscript reflected scribal corruption and that in the poem as originally composed, the name must have been an Old English form of a Germanic name reconstructable as *Wala-þewaz ("chosen servant"), attested in other ancient Germanic languages. In this argument, at the point of Beowulf's composition, Hrothgar's queen was called *Wælþēo. Though Gordon's argument was accepted by few scholars, it was supported and developed in 2017 by Leonard Neidorf, who saw the putative corruption of the character's name to be consistent with the widely accepted view that Beowulf originally included characters called Bēow and Unferþ, despite the manuscript consistently naming them as Beowulf and Hunferþ respectively: Neidorf argued that a scribe had changed *Wælþēo's name because it was unfamiliar to him, substituting the familiar name-element wealh and the later spelling þēow.[6]

Role in the poem

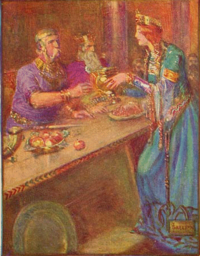

editWealhtheow (like Hygd) fulfills the important role of hostess in the poem.[8] The importance of this cup carrying practice is emphasized in lines 1161–1231. Here Wealhtheow, anxious that Hrothgar secures the succession for her own offspring, gives a speech and recompenses Beowulf for slaying Grendel with three horses and a necklace.

The necklace is called Brosinga mene, and the name is held to be either a corruption or a misspelling of OE Breosinga mene, ON Brisingamen,[9] Freyja's necklace. Richard North compares the gift of the necklace to Brosing, Freyja's Brisingamen[10] and he comments that,

- The wider Old Norse-Icelandic tradition attributes the Brisinga men or giroli Brisings (Brisinger's girdle c.900) to Freya who is at once the sister of Ingvi-freyr of the Vanir, the leading Norse goddess of love, and a witch with the power to revive the dead. Freya's acquisition of this necklace and its theft by Loki are the central incidents in Sorlaþattr.[10]

Wealhtheow has also been examined as a representative of Hrothgar's kingdom and prestige and a fundamental component to the functioning of his court. According to Stacy Klein, Wealhtheow wore “elaborate garb” to demonstrate the “wealth and power” of the kingdom.[11] As queen, Wealhtheow represents the “female's duty to maintain peace between two warring tribes” and to “signify the status of the court.”[12] While her position may appear ritualistic, she also maintains “the cohesiveness of the unity of the warriors.”[12] The role of queens in the early Germania was to foster “social harmony through active diplomacy and conciliation.”[13] Wealhtheow inhabits this role by constantly speaking to each of the men in her hall and reminding them of their obligations – obligations to their country, their family, or their king.

In a grimly ironic passage that would not be lost on the Anglo-Saxon audience of Beowulf[14] Wealhtheow commends her sons to Hroðulf's generosity and protection, not suspecting that he will murder her sons to claim the throne for himself.

All the qualities marking Wealhtheow as an ideal queen place her in contrast to Grendel's mother, who appears for the first time following a lengthy passage concerned with Wealhtheow and her sons.[15] The contrast between Wealhtheow and Grendel's mother echoes the parallels between Beowulf, Hrothgar, and Grendel.

Notes

edit- ^ Wealhtheow is identified as a Helming in the poem, i.e. belonging to the clan of Helm, the chief of the Wulfings (Widsith, 21)

- ^ Heaney, Seamus. Beowulf: A New Verse Translation. 136

- ^ Gregor Sarrazin 1897, Neue Beowulf-studien, Englische Studien 23, 221–267, at p. 228-230. See also Fr. Klaeber (Ed.), Beowulf and the Fight at Finnsburgh (Boston 1950), xxxiii, note 2.

- ^ e.g. G. Jones, Kings, Beasts and Heroes (Oxford 1972), 132–134.

- ^ S. Newton, The Origins of Beowulf and the pre-Viking Kingdom of East Anglia (D.S. Brewer, Woodbridge 1993), esp. p. 122-128.

- ^ a b c d Neidorf, Leonard (January 2018). "Wealhtheow and Her Name: Etymology, Characterization, and Textual Criticism". Neophilologus. 102 (1): 75–89. doi:10.1007/s11061-017-9538-4. ISSN 0028-2677.

- ^ Hill, Thomas D. "'Wealhtheow' as a Foreign Slave: Some Continental Analogues." Philological Quarterly 69.1 (Winter 1990): 106-12.

- ^ Porter, Dorothy (Summer–Autumn 2001). "The Social Centrality of Women in Beowulf: A New Context". The Heroic Age: A Journal of Early Medieval Northwestern Europe, heroicage.org, Issue 5. Archived from the original on 2006-08-19. Retrieved 2006-08-09.

- ^ Old English edition edited by James Albert Harrison and Robert Sharp.

- ^ a b Richard North, "The King's Soul: Danish Mythology in Beowulf" in the Origins of Beowulf: From Vergil to Wiglaf, (New York: Oxford University, 2006), 194

- ^ Klein, Stacy S. “Reading Queenship in Cynewulf’s Elene.” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. 33.1 (2003): 47-89. Project Muse.

- ^ a b Gardner, Jennifer. The Peace Weaver: Wealhþēow in Beowulf. Diss. Western Carolina University. March 2006.

- ^ Butler, Francis. “A Woman of Words: Pagan Ol’ga in the Mirror of Germanic Europe.” Slavic Review. 63.4 (Winter 2004): 771-793. JSTOR.

- ^ Wright, David. Beowulf. Panther Books, 1970. ISBN 0-586-03279-7. page 14

- ^ Trilling, Renée R. (2007). "Beyond Abjection: The Problem with Grendel's Mother Again". Australian and New Zealand Association of Medieval and Early Modern Studies (Inc.). 24 (1): 1–20 – via Project MUSE.

References

edit- Boehler, M. (1930). Die altenglischen Frauennamen, Germanische Studien 98. Berlin: Emil Ebering.

- Damico, Helen. Beowulf's Wealhþēow and the Valkyrie Tradition. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984.

- Damico, Helen. "The Valkyrie Reflex in Old English Literature." New Readings on Women in Old English Literature. Eds. Helen Damico and Alexandra Hennessey Olsen. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990. 176-89.

- Gordon, E. V. (1935). "Wealhpeow and related names". Medium Ævum (4): 168.

- Klaeber, Frederick (1950). Beowulf and the Fight at Finnsburgh (3rd ed.). Boston: tbs.

- Newton, Sam. The Origins of Beowulf and the pre-Viking Kingdom of East Anglia. D. S. Brewer, Woodbridge 1993.

- North, Richard. Origins of Beowulf: From Vergil to Wiglaf. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Osborn, Marijane (Summer–Autumn 2001). "The Wealth They Left Us:Two Women Author Themselves through Others' Lives in Beowulf". The Heroic Age: A Journal of Early Medieval Northwestern Europe, heroicage.org, Issue 5.

- Porter, Dorothy (2001). "The Social Centrality of Women in Beowulf: A New Context". The Heroic Age: A Journal of Early Medieval Northwestern Europe (5 (Summer–Autumn 2001)). Archived from the original on 2006-08-19. Retrieved 2006-08-09.

- Sarrazin, Gregor. "Neue Beowulf-studien," Englische Studien 23, (1897) 221-267.

- Trilling, Renée R. (2007). "Beyond Abjection: The Problem with Grendel's Mother Again". Australian and New Zealand Association of Medieval and Early Modern Studies (Inc). Volume 24, Number 1: 1-20 - via Project MUSE.

- Jurasinski, Stefan. The feminine name Wealhtheow and the problem of Beowulfian anthroponymy, Neophilologus (2007) [1].