White Deer Hole Creek is a 20.5-mile (33.0 km) tributary of the West Branch Susquehanna River in Clinton, Lycoming and Union counties in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. A part of the Chesapeake Bay drainage basin, the White Deer Hole Creek watershed drains parts of ten townships. The creek flows east in a valley of the Ridge-and-valley Appalachians, through sandstone, limestone, and shale from the Ordovician, Silurian, and Devonian periods.

| White Deer Hole Creek | |

|---|---|

White Deer Hole Creek near the Fourth Gap of South White Deer Ridge | |

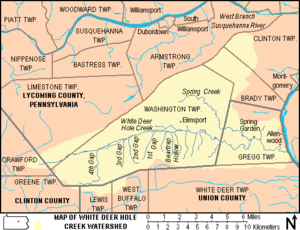

Map showing White Deer Hole Creek, its major tributaries and watershed | |

| Etymology | Lenape language Woap-achtu-woalhen |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| Counties | Clinton, Lycoming, Union |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Crawford Township, Clinton County |

| • coordinates | 41°05′19″N 77°11′38″W / 41.08861°N 77.19389°W[1] |

| • elevation | 2,180 ft (660 m)[2] |

| Mouth | West Branch Susquehanna River |

• location | Gregg Township, Union County |

• coordinates | 41°06′02″N 76°53′22″W / 41.10056°N 76.88944°W[1] |

• elevation | 445 ft (136 m)[2] |

| Length | 20.5 mi (33.0 km)[2] |

| Basin size | 67.2 sq mi (174 km2)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Mouth[4] |

| • average | 70.4 cu ft/s (1.99 m3/s)[4] |

| • minimum | 33 cu ft/s (0.93 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 111 cu ft/s (3.1 m3/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | near Elimsport[5] |

| • average | 4,200 cu ft/s (120 m3/s)[5] |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Spring Creek |

| • right | Beartrap Hollow |

As of 2006, the creek and its 67.2-square-mile (174 km2) watershed are relatively undeveloped, with 28.4 percent of the watershed given to agriculture and 71.6 percent covered by forest, including part of Tiadaghton State Forest. The western part of White Deer Hole Creek has very high water quality and is the only major creek section in Lycoming County classified as Class A Wild Trout Waters, defined by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission as "streams which support a population of naturally produced trout of sufficient size and abundance to support a long-term and rewarding sport fishery."[6] The rest of the creek and its major tributary (Spring Creek) are kept stocked. There are opportunities in the watershed for canoeing, hunting, and camping, and trails for hiking and horseback riding.

Historically, two paths of the native indigenous peoples ran along parts of White Deer Hole Creek. Settlers arrived by 1770, but fled in 1778 during the American Revolutionary War. They returned and the creek served as the southern boundary of Lycoming County when it was formed on April 13, 1795. A logging railroad ran along the creek from 1901 to 1904 for timber clearcutting, and small-scale lumbering continues. During World War II a Trinitrotoluene (TNT) plant, which became a federal prison in 1952, was built in the watershed. Most development is in the eastern end of the valley, with two unincorporated villages, a hamlet, and most of the farms (many Amish).

Name

editTwo etymologies have been suggested for White Deer Hole Creek's unusual name. According to Donehoo, it is a translation of the Lenape (or Delaware) Woap-achtu-woalhen (meaning "white-deer digs a hole").[7] It is Opauchtooalin on the earliest map showing the creek (1755), while a 1759 map has both Opaghtanoten and its translation, "White Flint Creek". By 1770 (when the first settlers arrived) a map has "White Deer hole".[7]

In 1870, 88-year-old John Farley gave a second explanation of the name. His family had settled on the banks of White Deer Hole Creek in 1787, and John's father John built a mill on the creek by 1789. The creek was named because "a white deer is said to have been killed at an early day in a low hole or pond of water that once existed where my father built his mill". The hole was "a large circular basin of low ground of some ten acres [(four ha)] in extent....after my father's mill and dam were built the water of the dam overflowed and covered the most of the hollow basin of ground."[8] The mill was just west of the mouth at the unincorporated village of Allenwood (then called Uniontown), now in Gregg Township in Union County.[8]

The name "White Deer Hole Creek" is unique in the USGS Geographic Names Information System and on its maps of the United States.[1] Although the whole creek is now referred to by this name, in 1870 the name applied only to the section from the confluence with Spring Creek east to its mouth, while the main branch west of Spring Creek was called "South Creek".[9] Meginness used this name in 1892 and it appeared on a 1915 state map of Union County (but not the 1916 Lycoming County map).[8][10][11] As of 2022 the name "South Creek" has disappeared, but there is still a "South Creek Road" on the right bank of the creek in Gregg Township from near the mouth of Spring Creek west to the county line.[12]

According to Meginness, the 17-mile (27 km) long and 8-mile (13 km) wide White Deer Hole Creek valley was just called "White Deer valley" by many in 1892, and this is still common.[8][13] Confusion about the names arises since White Deer Creek is the next creek south of White Deer Hole Creek (they are on opposite sides of South White Deer Ridge).[14] The Lenape name for White Deer Creek was Woap'-achtu-hanne (translated as "white-deer stream").[7]

Spring Creek is the only named tributary of White Deer Hole Creek. Five unnamed tributaries flow through named features of South White Deer Ridge. Going upstream in order they are: Beartrap Hollow, First Gap, Second Gap, Third Gap, and Fourth Gap.[15]

Course

editLycoming County is about 130 miles (210 km) northwest of Philadelphia and 165 miles (266 km) east-northeast of Pittsburgh. The source of White Deer Hole Creek is in Crawford Township, just over the Clinton County line. Both it and the western half of the creek are within Tiadaghton State Forest.[1][16] The creek flows east and soon crosses a natural gas pipeline and the Lycoming County line into Limestone Township.[15]

It soon flows into Washington Township, which has more of White Deer Hole Creek than any other township. It receives unnamed tributaries in the Fourth, Third, Second, and First Gaps of South White Deer Ridge on the south or right bank. The creek leaves Tiadaghton State Forest after the Third Gap (the forest itself continues along the ridge to the river), and stops being "Class A Wild Trout Waters" between the Second and First Gaps.[17] It receives the unnamed tributary in Beartrap Hollow 10.8 miles (17.4 km) upstream of its mouth, then passes south of the unincorporated village of Elimsport.[18]

White Deer Hole Creek then flows east into Gregg Township in Union County, receiving its major tributary, Spring Creek, on the left bank 3.6 miles (5.8 km) upstream of its mouth.[18] Spring Creek rises north of Elimsport in Washington Township and flows east-southeast, passing through Pennsylvania State Game Lands No. 252 and just south of the Federal Correctional Institute, Allenwood.[19]

The creek next flows just south of the hamlet of Spring Garden, then south of the village of Allenwood, where it has its confluence with the West Branch Susquehanna River.[1][20] The direct distance between the source and mouth is only 16 miles (26 km).[21] U.S. Route 15 and the Union County Industrial Railroad run north–south here along the river and cross the creek just before its mouth; however, this track is not in service as of 2022.[22][23] Pennsylvania Route 44 runs east–west roughly parallel to the creek between Elimsport and Allenwood. Township roads run along the eastern two-thirds of the creek, and smaller, more primitive roads follow it to near its source.[15]

From the mouth of White Deer Hole Creek it is 17.7 miles (28.5 km) along the West Branch Susquehanna River to its confluence with the Susquehanna River at Northumberland.[18] The elevation at the source is 2,180 feet (660 m), while the mouth is at an elevation of 445 feet (136 m). The difference in elevation, 1,735 feet (529 m), divided by the length of the creek of 20.5 miles (33.0 km) gives the average drop in elevation per unit length of creek or relief ratio of 84.6 feet/mile (16.0 m/km). The meander ratio is 1.14, so the creek's path is not entirely straight in its bed.[2] The meandering increases near the mouth.[15]

For its entire length, White Deer Hole Creek runs along the north side of South White Deer Ridge, an east–west ridge of the Appalachian Mountains. North White Deer Ridge and Bald Eagle Mountain form the northern edge of the creek valley. There are 24 unnamed tributaries on the south side of the creek, all flowing down the side of South White Deer Ridge, while there are only 11 tributaries on the north side, including Spring Creek.[15]

White Deer Creek, the next major creek to the south, flows along the other side of South White Deer Ridge in Union County and is just 1.9 miles (3.1 km) away (as measured along the West Branch Susquehanna River). The next major creek to the north is Muncy Creek, 10.2 miles (16.4 km) away along the river, but on the opposite bank. The next creek to the north on the same bank (except for the small Black Run) is Black Hole Creek, on the south side of Bald Eagle Mountain. It has a watershed area of 21.1 square miles (55 km2) and enters the river 4.0 miles (6.4 km) away at the borough of Montgomery.[2][18]

White Deer Hole Creek joins the West Branch Susquehanna River 17.66 miles (28.42 km) upstream of its mouth.[18]

Geology

editWhite Deer Hole Creek is in a sandstone, limestone, and shale mountain region, entirely in the Ridge-and-valley Appalachians.[2] South and North White Deer Ridge and Bald Eagle Mountain are composed of sedimentary Ordovician rock, while the valley rock is Silurian, with a small Devonian region closer to the river, in the north.[24] The watershed has no deposits of coal, nor natural gas or oil fields.[25][26] The creek is in a narrow mountain valley with steep slopes in its upper reaches. In its middle and lower reaches it has steep mountain slopes to the south, and a wide valley with rolling hills and gentle slopes to the north. The channel pattern is transitional, with a trellised drainage pattern.[2]

From 1961 to 1995, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) operated one stream gauge on White Deer Hole Creek at the Gap Road bridge (upstream of Elimsport), for the uppermost 18.2 square miles (47 km2) of the watershed. The highest yearly peak discharge measured at this site was 4,200 cubic feet (120 m3) per second and the highest yearly peak gauge height was 11.83 feet (3.61 m), both on June 22, 1972, during Hurricane Agnes. The lowest yearly peak discharge in this time period was 135 cubic feet (3.8 m3) per second and the lowest yearly peak gauge height was 4.29 feet (1.31 m), both on November 26, 1986.[5] The USGS also measured discharge at Allenwood, very near the creek's mouth, as part of water quality measurements on seven occasions between 1970 and 1975. The average discharge was 70.4 cubic feet (1.99 m3) per second, and ranged from a high of 111 cubic feet (3.1 m3) per second to a low of 33 cubic feet (0.93 m3) per second.[4] There are no other known stream gauges on the creek.

Watershed

editThe White Deer Hole Creek watershed consists of 0.08 percent of the area of Clinton County, 4.40 percent of the area of Lycoming County, and 3.67 percent of the area of Union County. Neighboring watersheds are the West Branch Susquehanna River and its minor tributaries (north and east), White Deer Creek (south), and Fishing Creek (west).[3]

In 2000, the White Deer Hole Creek watershed population was 2,672.[3] In the 1970s, Amish began moving to the Elimsport area from Lancaster County. In 1995 there were over 200 Amish in more than twenty families.[13] In comparison, Washington Township's population was 1,619 in 2010 (and 1769 in 2020).[27] Elimsport has Amish harness, machine repair, and food shops, and a new one-room school was built nearby in 1997.[28][29]

The watershed area is 67 square miles (170 km2), with 48 square miles (120 km2) of forest and 19 square miles (49 km2) for agriculture. By area, 1.1 percent of the watershed lies in Clinton County (in Crawford and Greene Townships), 81.6 percent lies in Lycoming County (in Brady, Clinton, Limestone, and Washington Townships), and 17.3 percent lies in Union County (in Gregg, Lewis, West Buffalo, and White Deer Townships).[3]

Spring Creek is the major tributary, draining an area of 21.1 square miles (55 km2) or 31 percent of the total White Deer Hole Creek watershed. No other tributaries are named and only the area of the tributary in Beartrap Hollow is known, with 0.42 square miles (1.1 km2) or 0.63 percent of the total.[18]

Water quality and pollution

editClearcutting of forests in the early 20th century and the ordnance plant in the Second World War adversely affected the White Deer Hole Creek watershed's ecology and water quality.[30][31] Agricultural runoff was and is another potential source of pollution. Gregg Township had no wastewater treatment plant until an 800,000-gallon/day (304 m3/day) plant was built along the river just north of the creek for the federal prison (90 percent) and village of Allenwood (10 percent).[32] The drainage basin has been designated by Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection as "a high quality watershed" since 2001.[33]

The mean annual precipitation for White Deer Hole Creek is 40 to 42 inches (1,016 to 1,067 mm).[2] Pennsylvania receives the most acid rain of any state in the United States. Because the creek is in a sandstone, limestone, and shale mountain region, it has a relatively low capacity to neutralize added acid. This makes it especially vulnerable to acid rain, which poses a threat to the long-term health of the plants and animals in the creek.[34] The total alkalinity of the "Class A Wild Trout Waters" is 2 for the 4.7 miles (7.6 km) of White Deer Hole Creek so classified, and 13 for the 3.0-mile (4.8 km) unnamed tributary in the Fourth Gap.[6]

Recreation

editEdward Gertler writes in Keystone Canoeing that White Deer Hole Creek "offers a good springtime beginner cruise through a pretty, agricultural valley" with "many satisfying views" and "good current and many easy riffles".[35] Canoeing and kayaking are possible in spring and after hard rain, with 10.6 miles (17.1 km) of Class 1 whitewater on the International Scale of River Difficulty from Back Road bridge east to U.S. Route 15 (the mouth). One can start further upstream at the Gap Road bridge, for 2.0 miles (3.2 km) of Class 2 whitewater, but strainers are more of a problem here.[35]

White Deer Hole Creek is designated by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission as a "Class A Wild Trout Waters" stream, from the source downstream to the Township Road 384 (Gap Road) bridge. The unnamed tributary in Fourth Gap is also "Class A Wild Trout Waters". The creek downstream from the bridge, as well as Spring Creek, have been designated as approved trout waters by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission and are stocked with trout and may be fished during trout season.[17] Other fish found in the creek and river include carp, catfish, pickerel, and pike.[32]

Hunting, trapping, and fishing are possible with proper licenses in Tiadaghton State Forest and the 3,018 acres (1,221 ha) in State Game Lands No. 252.[36] In 2002, a Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources report on "State Forest Waters with Special Protection" rated White Deer Hole Creek from its source to Spring Creek as a "High Quality-Cold Water Fishery".[37] In addition to these public lands, there are private hunting and fishing clubs and cabins along White Deer Hole Creek and its tributaries. Popular game species include American black bear, white-tailed deer, ruffed grouse, and wild turkey.[38]

Part of the 261-mile (420 km) Pennsylvania Mid State Trail, marked with orange blazes to indicate it is solely for hiking, runs along a section of White Deer Hole Creek from west of the Fourth Gap to beyond the source.[38] There are other hiking trails in the watershed, and the Third Gap, Metzger, Mud Hole, Pennsylvania Mid State, Sawalt, and Mountain Gap trails are part of the 120-mile (190 km) Central Mountains Shared Use Trails System, marked with red blazes, in Tiadaghton and Bald Eagle State Forests in Union, Lycoming, and Clinton Counties.[39]

Roads and trails in the state forest are also open for horseback riding and mountain biking.[39] Some trails are dedicated to cross-country skiing and snowmobiling in winter. The state forest is open for primitive camping, although certain areas require a permit. Small campfires are allowed, except from March to mid-May and October through November, or by order of the district forester, when self-contained stoves are allowed.[38]

History

editNative American paths

editThe first recorded inhabitants of the Susquehanna River valley were the Susquehannocks, an Iroquoian speaking people. Their name meant "people of the muddy river" in the Algonquian, but their name for themselves is unknown. Decimated by diseases and warfare, they had largely died out, moved away, or been assimilated into other tribes by the early 18th century. The lands of the West Branch Susquehanna River valley were then chiefly occupied by the Munsee phratry of the Lenape (or Delaware), and were under the nominal control of the Five (later Six) Nations of the Iroquois. Two important paths of these native indigenous peoples ran along parts of White Deer Hole Creek.[8]

The Great Island Path was a major trail that ran north along the Susquehanna River from the Saponi village of Shamokin at modern Sunbury, fording the river there and following the west bank of the West Branch Susquehanna River north until White Deer Hole valley. The path turned west at Allenwood and followed White Deer Hole Creek until about the present location of Elimsport. There it headed northwest, crossed North White Deer Ridge and passed west through the Nippenose valley, then turned north and crossed Bald Eagle Mountain via McElhattan Creek and ran along the south bank of the river to the Great Island (near the present day city of Lock Haven). The stretch from the mouth of the creek to the Nippenose valley is approximately followed by Route 44. From the Great Island, the Great Shamokin Path continued further west to the modern boroughs of Clearfield and Kittanning, the last on the Allegheny River.[41]

Culbertson's Path followed White Deer Hole Creek west from Allenwood, then followed Spring Creek north, crossed Bald Eagle Mountain and followed Mosquito Run to the river at the current borough of Duboistown. Here it crossed the river to "French Margaret's Town" (western modern day Williamsport) before joining the major Sheshequin Path, which led north up Lycoming Creek to the North Branch of the Susquehanna River, modern New York, and the Iroquois there. These trails were only wide enough for one person, but settlers in White Deer Hole valley broadened the path to DuBoistown to take grain to Culbertson's mill on Mosquito Run, hence the name.[41] Culbertson's Path was used as a part of the Underground Railroad until the American Civil War began in 1861. Escaped slaves would often wade in creeks to hide their scent from pursuing bloodhounds.[42] In 2009, there is still a "Culbertson's Trail", for hiking over Bald Eagle Mountain from Pennsylvania Route 554 to Duboistown.[15]

Lycoming County boundaries

editWhen Lycoming County was organized on April 13, 1795, the bill passed by the Pennsylvania legislature defined the new county's boundaries thus:

That all that part of Northumberland County lying northwestward of a line drawn from the Mifflin county line on the summit of Nittany mountain; thence running along the top or highest ridge of said mountain, to where White Deer Hole creek runs through the same; and from thence by a direct line crossing the West Branch of Susquehanna, at the mouth of Black Hole creek to the end of Muncy Hills; thence along the top of Muncy Hills and the Bald Mountain to the Luzerne county line, shall be, and the same is hereby erected into a separate county, to be henceforth called and known by the name of Lycoming County.[8] [emphasis added]

The borders of the county have changed considerably since, but the White Deer Hole Creek watershed still approximates the county line in the south. Until 1861, what is now Gregg Township in Union County was a part of Brady Township in Lycoming County. Thus, until the start of the American Civil War, almost all of White Deer Hole Creek and its watershed were part of Lycoming County.[8]

Early inhabitants

editPrior to construction, the site of the wastewater treatment plant yielded archeological evidence of habitation by indigenous peoples from the Paleo-Indian, Archaic, and Woodland periods.[32] The only Native American inhabitant of the valley whose name is known, "Cochnehaw", lived near the mouth of White Deer Hole Creek. White Deer Hole Creek was acquired by the colonial government of Pennsylvania on November 5, 1768, as part of the "New Purchase" in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. The first settlers came to the valley in 1769 or 1770, and by 1778 there were 146 landowners on the township tax rolls (though many likely resided elsewhere.)[8]

In the American Revolutionary War, settlements throughout the Susquehanna valley were attacked by Loyalists and Native Americans allied with the British. After the Wyoming Valley battle and massacre in the summer of 1778 (near what is now Wilkes-Barre) and smaller local attacks, the "Big Runaway" occurred throughout the West Branch Susquehanna valley. Settlers fled from feared and actual attacks by the British and their allies. Settlers abandoned their homes and fields, drove their livestock south, and towed their possessions on rafts on the river to Sunbury. Their abandoned property was burnt by the attackers. Some settlers soon returned, only to flee again in the summer of 1779 in the "Little Runaway".[43]

Sullivan's Expedition helped stabilize the area and encouraged resettlement, which continued after the war. However, in 1787 there were only fourteen families in the valley: five on the river banks, five on White Deer Hole Creek between Spring Creek and the river, two on Spring Creek, and two on the creek west of Spring Creek. Six families left the area not long after 1787.[9] The first grist mill was built on the creek in 1789, and four more were built in 1798, 1815, 1817, and 1842.[8]

Lumber and logging railroad

editBeginning with the first settlers, much of the land along White Deer Hole Creek was slowly cleared of timber. Small sawmills were constructed in the 19th century, and a much larger lumber operation was run by the Vincent Lumber Company from 1901 to 1904. The company built a narrow gauge 42 inches (1,100 mm) railroad from Elimsport 5 miles (8.0 km) west into timber, and a line east to Allenwood and the Reading Railroad there. The lumber railroad, which ended near the Fourth Gap, ran parallel to the creek. It was incorporated on June 24, 1901, (around the time of construction) as the "Allenwood and Western Railroad". The lumbering operation ceased in 1904 when the forests were gone. The railroad was torn up, and its one second-hand Shay locomotive was moved to the Vincent Lumber Company operation at Denholm in Juniata County.[44]

From 1900 to 1935, much of what is now Tiadaghton State Forest was purchased by Pennsylvania from lumber companies that had no further use for the clear-cut land. In the 1930s there were seven Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps to construct roads and trails in the forest.[38] CCC Camp S-125-Pa (Elimsport) was located 15 miles (24 km) west of Allenwood along the creek, between the Third and Fourth Gaps.[45]

Small-scale lumbering continues in the watershed, but the forest is certified as well-managed "in an environmentally sensitive manner" and lumber from it qualifies for a "green label".[38] Gertler reports lumber operations along White Deer Hole Creek near Elimsport in the early 1980s.[35] A sawmill owned and operated by Amish on Route 44 in Elimsport burned down on May 10, 2006, causing $500,000 in damages, but was expected to be back in operation in a month;[46] it has since reopened. Despite this small-scale lumbering, the forests have grown back since the clear cutting of the 19th century, and are mixed oak, with blueberry and mountain laurel bushes. White Deer Hole Creek and its tributaries also have stands of hemlock and thickets of rhododendron along them.[39]

Ordnance plant to federal prison and game lands

editDuring the Second World War, the federal government built the $50 million Susquehanna Ordnance Depot to make TNT on 8,500 acres (3,400 ha), partially in the White Deer Hole Creek watershed. In the spring of 1942, residents were evicted by eminent domain from 163 farms and 47 other properties in Gregg Township in Union County and Brady, Clinton, and Washington Townships in Lycoming County. The village of Alvira in Gregg Township disappeared.[31] Alvira was founded in 1825 as "Wisetown" and had 100 inhabitants by 1900. Although the inhabitants were told they could return after the war, almost all the buildings seized were razed. Only some cemeteries and the nearby "Stone Church" remain.[47] Construction of the plant involved some 10,000 people, and it took 3,500 to 4,500 employees to run the plant with its more than 200 buildings and 149 storage bunkers for TNT and high explosives, as well as storage racks of bombs. However, the need for TNT was lower than originally estimated and the project was nearly abandoned. By 1945, the only workers left at the depot were guards.[48]

The depot closed after the war and the land was used by the United States Army for testing.[47] In 1950, the Federal Bureau of Prisons was given 4,000 acres (1,600 ha) of the plant site, and began housing prisoners from the Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary there in 1952. In 1957 the "Allenwood Prison Camp" was built, which became the "Federal Correctional Institute, Allenwood". This was greatly expanded in the early 1990s to become "the largest federal prison facility" in the United States. North of the White Deer Hole Creek watershed, some of the land was sold to make the "White Deer Golf Course" in Clinton Township, and in 1973, 125 acres (51 ha) of prison land in Brady Township were leased to Lycoming County for its landfill (which serves five counties).[31]

The remaining 3,018 acres (1,221 ha) were given to Pennsylvania and became State Game Lands 252.[36] Many of the 149 concrete bunkers remain,[48] but it is "a diverse mix of mature forest, impoundments, and brushy thickets, as well as a local hotspot for a variety of birds during migration".[49] The watershed is a haven for wildlife. Common animals in the game lands include painted and common snapping turtles, muskrats, frogs, eastern cottontails, red foxes, and white-tailed deer, while birds include golden-winged, hooded, and blue-winged warblers, red-shouldered hawks, wood ducks, tundra swans, pied-billed grebes, American bitterns, herons, and belted kingfishers.[49] The first barn owls to be banded in Lycoming County were in a barn near Elimsport in 2006.[50] Gray squirrels, groundhogs, raccoons, crows, red-tailed hawks, downy woodpeckers, cardinals, blue jays, American robins, nuthatches, titmice, and sparrows are also found in the White Deer Hole Creek watershed.[32]

See also

edit- Delaware Run, next tributary of the West Branch Susquehanna River going downriver (left bank)

- Black Run (West Branch Susquehanna River), next tributary of the West Branch Susquehanna River going upriver (right bank)

- List of rivers of Pennsylvania

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Geographic Names Information System, United States Geological Survey (1979-08-02). "Geographic Names Information System Feature Detail Report: White Deer Hole Creek". Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shaw, Lewis C. Pennsylvania Gazetteer of Streams Part II (Water Resources Bulletin No. 16). Prepared in Cooperation with the United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey (1st ed.). Harrisburg, PA: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Environmental Resources. p. 173. OCLC 17150333.

- ^ a b c d "Chesapeake Bay Program: Watershed Profiles: The White Deer Hole Creek - At Allenwood Watershed". Chesapeake Bay Program Office, 10 Severn Avenue, Suite 109, Annapolis, MD 21403. Archived from the original on 2009-04-18. Retrieved 2006-03-21.

- ^ a b c United States Geological Survey. "Water Quality Samples for the Nation, USGS 01553110 White Deer Hole Creek at Allenwood, PA". Charts, Graphs. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ a b c United States Geological Survey. "Peak Streamflow for the Nation, USGS 01553050 White Deer Hole Creek near Elimsport, PA". Charts, Graphs, Map. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ a b "Class A Wild Trout Waters" (PDF). Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC). 2009-02-14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ^ a b c Donehoo, Dr. George P. (1999) [1928]. A History of the Indian Villages and Place Names in Pennsylvania (Second Reprint ed.). Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Wennawoods Publishing. p. 252. ISBN 1-889037-11-7. Also see the following, which cites Donehoo: Runkle, Stephen A. (September 2003). "Native American Waterbody and Place Names Within the Susquehanna River Basin and Surrounding Subbasins (Publication No. 229)" (PDF). Susquehanna River Basin Commission. p. 23. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Meginness, John Franklin (1892). "Chapter XXXIX. Washington, Clinton, Armstrong, and Brady.". History of Lycoming County, Pennsylvania: including its aboriginal history; the colonial and revolutionary periods; early settlement and subsequent growth; organization and civil administration; the legal and medical professions; internal improvement; past and present history of Williamsport; manufacturing and lumber interests; religious, educational, and social development; geology and agriculture; military record; sketches of boroughs, townships, and villages; portraits and biographies of pioneers and representative citizens, etc. etc (1st ed.). Chicago, IL: Brown, Runk & Co. ISBN 0-7884-0428-8. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

(Note: ISBN refers to Heritage Books July 1996 reprint. URL is to a scan of the 1892 version with some OCR typos).

- ^ a b Wolfinger, J.F.; contributed to USGenWeb Archives by Harold E. Bower, Jr. (1870-09-02). "White Deer Hole Valley". Lycoming Gazette and West Branch Bulletin. p. 4. Archived from the original on 2008-02-09. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ Pennsylvania State Highway Department (1915-05-01). "Map of the Public Roads in Union County, Pennsylvania" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-11-17. Note: shows "White Deer Hole Creek" and "South Creek"

- ^ Pennsylvania State Highway Department (1916-12-01). "Map of the Public Roads in Lycoming County, Pennsylvania" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-11-17. Note: shows only "White Deer Hole Creek"

- ^ Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Bureau of Planning and Research, Geographic Information Division. 2022 General Highway Map of Snyder County and Union County (Note: shows White Deer Hole Creek and almost all streams feeding it in Union County) (PDF) (Map). Retrieved 2022-11-17.

{{cite map}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ruoff, Mary (1995-11-12). "Amish, New Homes Bringing Changes to Elimsport". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. p. A3. Note: refers to "White Deer valley"

- ^ Note: For a document that refers (mistakenly) to both "White Deer Creek valley" and to "White Deer Creek" for White Deer Hole Creek and its valley, see: The Lycoming County Planning Commission; and the Lycoming County Department of Planning and Community Development (2009-02-09). "The Comprehensive Plan for Lycoming County, PA Phase II" (PDF). Completed and Adopted by the Lycoming County Board of Commissioners. pp. 227, 234. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ a b c d e f Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (2022-05-20). "Tiadaghton State Forest Map" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ^ USGS Topographic Map, Carroll Quad (Map). Cartography by United States Geological Survey. ACME Mapper 2.0. Retrieved 2022-11-19.

- ^ a b "PFBC County Guide". Searchable map. Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC). Archived from the original on 2010-05-29. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Bureau of Watershed Management, Division of Water Use Planning, Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (2001). Pennsylvania Gazetteer of Streams (PDF). Prepared in Cooperation with the United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Bureau of Planning and Research, Geographic Information Division. 2022 General Highway Map of Lycoming County (PDF) (Map). Retrieved 2022-11-19.

{{cite map}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Note: shows White Deer Hole Creek and almost all streams feeding it. - ^ USGS Topographic Map, Allenwood Quad (Map). Cartography by United States Geological Survey. ACME Mapper 2.0. Retrieved 2022-11-19.

- ^ Michels, Chris (1997). "Latitude/Longitude Distance Calculation". Archived from the original on 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2006-03-21.

- ^ North Shore Railroad System. "The North Shore Railroad Company & Affiliates: Union County Industrial Railroad". Retrieved 2022-11-19. Note: The list of stations and current map show New Columbia is the northernmost point served, and do not include Allenwood.

- ^ Bureau of Rail Freight, Ports, & Waterways, Bureau of Planning and Research (August 2022). Pennsylvania Railroad Map (PDF) (Map). Pennsylvania Department of Transportation. Retrieved 2022-11-19.

{{cite map}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey. "Geologic Map of Pennsylvania" (PDF). Map. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2001. Retrieved 2006-07-24.

- ^ Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey. "Distribution of Pennsylvania Coals" (PDF). Map. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 18, 2000. Retrieved 2006-07-24.

- ^ Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey. "Oil and Gas Fields of Pennsylvania" (PDF). Map. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 18, 2000. Retrieved 2006-07-24.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021". Census.gov. US Census Bureau. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Pauling, Dena (2005-08-25). "Amish food store near Elimsport will remain open". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. p. B1, B3.

- ^ Barr, James P. (1997-07-24). "Amish Don't Want 'Anything Fancy': One-Room School Gets Zoning OK". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. p. A1, A6.

- ^ Natural Resources Defense Council. "What Is Clearcutting?". Retrieved 2006-11-08.

- ^ a b c "History". Organizations United for the Environment. June 1988. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- ^ a b c d United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Prisons; prepared with the assistance of Louis Berger & Associates, Inc. (1991-11-15). Allenwood, Pennsylvania Federal Correctional Complex Wastewater Treatment Facility Environmental Assessment.

- ^ Lycoming County Planning Commission; prepared by Science Applications International Corp. (Sep 2001). Water Supply Plan (PDF). p. 18. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- ^ "Acid Precipitation". Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. Archived from the original on April 4, 2006. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ a b c Gertler, Edward (1985). Keystone Canoeing: A Guide to Canoeable Waters of Eastern Pennsylvania (1st ed.). Silver Spring, Maryland: Seneca Press. p. 292. ISBN 0-9605908-2-X.

- ^ a b "HuntingPA.com Game Lands: Pennsylvania State Game Lands, their general location and acreage". Archived from the original (Searchable Database) on 2006-10-06. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

- ^ "State Forest Waters with Special Protection" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2004. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ a b c d e Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Forestry (November 2004). "A Public Use Map for Tiadaghton State Forest" (Map / Brochure).

- ^ a b c Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Forestry (2002). "Central Mountains Shared Use Trails System: Union, Lycoming and Clinton Counties, Bald Eagle and Tiadaghton State Forests" (Map / Brochure).

- ^ "A Map Of The State Of Pennsylvania. Howell, Reading, 1792". The David Rumsey Map Collection, Cartography Associates. Retrieved 2008-06-22. Note: This website has more information on the mapw and the complete file in .sid.

- ^ a b Wallace, Paul A.W. (1987). Indian Paths of Pennsylvania (Fourth Printing ed.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. pp. 42, 63–64. ISBN 0-89271-090-X. Note: ISBN refers to 1998 impression.

- ^ Produced by North Star and WVIA-TV (1997). Follow The North Star To Freedom (documentary). Scranton, Pennsylvania: WVIA-TV. Archived from the original on 2009-03-05 – via PBS. 60 minutes. Retrieved on 2009-03-03.

- ^ A Picture of Lycoming County (PDF). The Lycoming County Unit of the Pennsylvania Writers Project of the Work Projects Administration (First ed.). The Commissioners of Lycoming County Pennsylvania. 1939. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Taber, Thomas T., III (1987). Railroads of Pennsylvania Encyclopedia and Atlas. Thomas T. Taber III. ISBN 0-9603398-5-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Pennsylvania CCC Archive: Camp Information for S-125-Pa". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-19. Note: this mistakenly refers to the camp as "Elmsport" instead of "Elimsport"

- ^ Holmes, Philip A. (2006-05-13). "Fire claims Route 44 sawmill". Williamsport Sun-Gazette.

- ^ a b Hunsinger Jr., Lou (2000-05-14). "Alvira: an explosive ghost town". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. p. B-1.

- ^ a b Brenneman, Pamela A. (1997-11-02). "State Ordnance Works Bunkers Remain". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. p. B-5.

- ^ a b Audubon Pennsylvania; Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (2004). Susquehanna River Birding and Wildlife Trail. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. pp. 34, 35. Archived from the original (Searchable database) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Note: This guide is available both as a book (page numbers given) and website (URL given). - ^ Long, Eric (2006-09-10). "Tracking Ghosts: Barn owls found, banded near Elimsport". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. p. F1, F6.

External links

edit- Susquehanna River Watersheds Map

- Official Clinton County Map of Crawford Township, showing source of White Deer Hole Creek (unlabeled)

- Official Lycoming County Floodplain map

- Official Union County map