The 1900 United States presidential election took place after an economic recovery from the Panic of 1893 as well as after the Spanish–American War, with the economy, foreign policy, and imperialism being the main issues of the campaign.[1] Ultimately, the incumbent U.S. president William McKinley ended up defeating the anti-imperialist William Jennings Bryan and thus won a second four-year term in office.

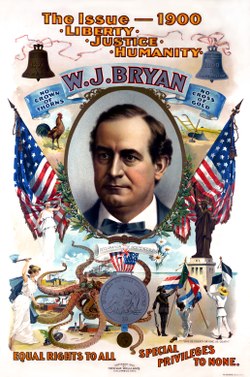

| William Jennings Bryan for President | |

|---|---|

| |

| Campaign | U.S. presidential election, 1900 |

| Candidate | William Jennings Bryan U.S. representative for Nebraska's 1st district (1891–1895) Adlai Stevenson I 23rd vice president of the United States (1893-1897) |

| Affiliation | Democratic Party |

| Status | Lost general election: November 6, 1900 |

The nomination fight

editInitially, Admiral George Dewey was the front-runner for the 1900 Democratic presidential nomination after his 1898 victory at the Battle of Manila Bay (during the Spanish–American War).[2] However, the fact that he married a Catholic widow (and gave her a house that grateful citizens had donated to him) as well his lack of knowledge about the role and power of the U.S. Presidency (Dewey said that the U.S. president merely executed the laws that the U.S. Congress passed) caused support for Dewey's candidacy to crumble.[2]

With the implosion of Dewey's candidacy, 1896 Democratic presidential nominee and former congressman William Jennings Bryan became the front-runner for the 1900 Democratic presidential nomination.[2] Even though various prominent Democrats tried to convince Bryan to drop his support of free silver (due to the fact that, unlike in the 1896 election, the economy was recovering and in good shape at this point in time), Bryan refused and threatened to run as an independent if the Democrats didn't adopt a pro-free silver plank.[2][3] Ultimately, Bryan won out and free silver was put into the 1900 Democratic platform by a one-vote margin--with Bryan becoming the 1900 Democratic presidential nominee.[2] In addition, the Democrats criticized the Republicans for their imperialism, for the Philippine–American War, and for the proliferation of trusts.[2][3]

Meanwhile, the Republicans re-nominated incumbent U.S. president William McKinley and chose New York governor Theodore Roosevelt as McKinley's running mate (McKinley's first vice president, Garret Hobart, had died in 1899).[2]

Campaign

editDuring the campaign, McKinley and the Republicans criticized Bryan's adherence support of free silver, claimed credit for the nation's economic recovery from Panic of 1893, called for lower taxes, a larger merchant marine, and an interoceanic canal in Central America.[2] In addition, McKinley argued that trusts were "dangerous conspiracies against the public good and should be made the subject of prohibitory or penal legislation."[2] Also, McKinley and the Republicans rejected both immediate independence for the Philippines and Bryan's idea of a protectorate for them, claiming that a Philippine protectorate would leave the U.S. responsible for the Philippines without the authority to meet its obligations.[2]

Meanwhile, McKinley's campaign manager and Ohio Senator Mark Hanna raised $2.5 million ($53.2 million in 2002 dollars), a million less than in 1896, but five times more than Democrats raised in 1900.[2] In addition, the Hanna-led Republican National Committee distributed 125 million pieces of campaign literature, including McKinley's letter of acceptance translated into German, Polish, and other languages.[2] During the campaign, McKinley's running mate Theodore Roosevelt vehemently criticized the Democrats and their platform (while also defending the gold standard).[2] Meanwhile, Bryan ran against the imperialism of McKinley and the Republicans and argued that imperialism is directly opposed to basic American values.[4] In addition, Bryan campaigned in favor of campaign finance reform and associated Republicans with big business and trusts (and their abuses) following a gaffe by Hanna (where he said that trusts no longer exist because they were outlawed).[2][5] While Bryan made a whopping 546 speeches to an audience of two-and-a-half million people during the 1900 campaign, Theodore Roosevelt's speeches during this campaign ended up reaching more people (with Roosevelt giving 673 speeches to an audience of three million people).[2][6] In addition, Bryan was hurt by the inadequate financing and organization of the Democratic Party in 1900.[2][6]

Results

editUltimately, McKinley won the popular vote by a 52% to 46% margin and won the electoral vote by a 292 to 155 margin.[6][3] Indeed, McKinley's victory margin was greater than it had been in 1896, and might have been even larger had it not been for the intimidation of Black voters in the Southern United States (in the South, only 40% of all eligible voters actually voted in 1900).[6] In addition, Republicans picked up two seats in the U.S. Senate and 11 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1900, raising their totals to 57 seats in the Senate and 198 seats in the House.[6]

Overall, the 1900 election continued the political realignment which was begun by the 1896 election, having established the Republicans as the dominant political party in the U.S. until the 1920s.[6]

References

edit- ^ "HarpWeek | Elections | 1900 Overview". Elections.harpweek.com. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "HarpWeek | Elections | 1900 Overview". Elections.harpweek.com. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- ^ a b c Gould, Lewis L. "William McKinley: Campaigns and Elections". Miller Center. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- ^ Michael E. Eidenmuller. "William Jennings Bryan - "Against Imperialism"". American Rhetoric. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- ^ "William Jennings Bryan Recognition Project". Agribusinesscouncil.org. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- ^ a b c d e f "HarpWeek | Elections | 1900 Overview". Elections.harpweek.com. Retrieved 2017-09-20.