Wilsons Promontory,[1] is a peninsula that forms the southernmost part of the Australian mainland, located in the state of Victoria.

| Wilsons Promontory | |

|---|---|

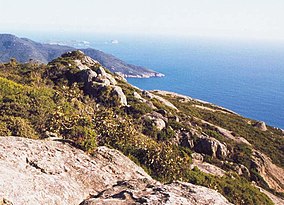

Looking south from Mount Oberon on Wilsons Promontory towards the southern tip of the Australian mainland. | |

Location of Wilsons Promontory in Victoria | |

| Location | Gippsland, Victoria, Australia |

| Coordinates | 39°02′S 146°23′E / 39.033°S 146.383°E |

South Point at 39°08′06″S 146°22′32″E / 39.13500°S 146.37556°E is the southernmost tip of Wilsons Promontory and hence of mainland Australia. Located at nearby South East Point, (39°07′S 146°25′E / 39.117°S 146.417°E) is the Wilsons Promontory Lighthouse. Most of the peninsula is protected by the Wilsons Promontory National Park and the Wilsons Promontory Marine National Park.

Human history

editThe promontory was first occupied by indigenous Koori people at least 6,500 years prior to European arrival.[2] Middens along the western coast indicate that the inhabitants subsisted on a seafood diet.[3]

The promontory is mentioned in dreamtime stories, including the Bollum-Baukan, Loo-errn and Tiddalik myths.[4][3] It is considered the home of the spirit ancestor of the Brataualung clan - Loo-errn.[5] The area remains highly significant to the Gunai/Kurnai and the Boon wurrung people, who consider the promontory to be their traditional country/land.[4] The land is now owned by the Boonwurung, Bunurong and Gunaikurnai people.

The first European to see the promontory was George Bass in January 1798.[6] He initially referred to it as "Furneaux's Land" in his diary, believing it to be what Captain Furneaux had previously seen. But on returning to Port Jackson and consulting Matthew Flinders he was convinced that the location was so different it could not be that land.[7]

Seal hunting was conducted in the area in the 19th century.[8] Shore-based whaling was also carried out in a cove at Wilsons Promontory from at least 1837. It was still underway in 1843 at Lady's Bay (Refuge Cove).[9]

Throughout the 1880s and '90s a public campaign to protect the area as a national park was waged, including by the Field Naturalists' Club of Victoria.[10] The promontory has been a national park, to one degree or another, since 1898. Wilsons Promontory National Park, also known locally as "the Prom", contains the largest coastal wilderness area in Victoria. Until the 1930s, when the road was completed, it was accessible only by boat.[10] The site was closed to the public during World War II, as it was used as a commando training ground. The only settlement within Wilsons Promontory is Tidal River which lies 30 kilometres (19 mi) south of the park boundary and is the focus for tourism and recreation. This park is managed by Parks Victoria.[11] In 2005 a burn started by staff got out of control and burnt 13% of the park, causing the evacuation of campers.[12] In 2009, a lightning strike near Sealer's Cove started a fire that burned over 25,000 hectares (62,000 acres). Much of the area had not been burned since 1951.[13] The fire began on 8 February, the day after "Black Saturday", where an intense heat wave, combined with arson, faulty electrical infrastructure and natural causes, led to hundreds of bushfires burning throughout the state of Victoria. Although the fire burned to within 1 kilometre (0.62 mi), the Tidal River camping area and park headquarters were unaffected. The park reopened to the public one month after the incident and the burned areas quickly regrew.[14] Despite the damage, the natural beauty of the area remained largely intact.[15]

In March 2011 a significant rainfall event led to major flooding of the Tidal River camping area. The bridge over Darby River was cut, leaving no vehicle access to Tidal River, leading to the evacuation of all visitors by helicopter over the following days, and the closure of the southern section of the park. In September 2011 public access to Tidal River was reopened following repair of the main access road, and the bridge at Darby River. All sections of the park south of Tidal River were closed while further repairs of tracks and footpaths were undertaken. The park was fully re-opened by Easter of 2012.

Tourists may choose basic or glam, cabins or camping (powered/unpowered) if they wish to stay inside Wilsons Promontory National Park. Many however choose to stay in accommodation just outside the Park in Yanakie, where they can still view the Wisons Promontory mountains and scenery and be only minutes from the Park's free entrance.

There are overnight hiking tracks[16] with two key circuits, one in the north and one in the south. The southern circuit is more popular with overnight hikers with several camping areas suited to wild camping. Camping is only allowed in the designated areas to reduce damage to the bush.

Name

editThe promontory is also known as "Yiruk" or "Wamoon" by some traditional owner groups.[17] From the early 19th century, it has also been known as Wilsons Promontory. It was given this name by Governor Hunter on the recommendation of Matthew Flinders and George Bass:

"At our recommendation governor Hunter called it WILSON'S PROMONTORY, in compliment to my friend Thomas Wilson, Esq. of London."[6]

Despite Wilson being significant enough for such a large amount of land to be named in his honour, he had slipped into obscurity until 2023, when new research was published by the Royal Australian Historical Society. Wilson was in fact one of the most important promoters of the study of the natural history of New South Wales, as Eastern Australia was then known, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was a member of both the Society for Promoting Natural History and the Linnean Society, a wealthy apothecary, a patron of surgeon and botanical collector John White and supporter of Flinders. White dedicated his far-reaching and substantial account of the First Fleet to Wilson, entitled Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales[18]

Geography and wildlife

editCoastal features include expansive intertidal mudflats, sandy beaches and sheltered coves interrupted by prominent headlands and plunging granite cliffs in the south, backed by coastal dunes and swamps. The promontory is surrounded by a scatter of small granite islands which, collectively, form the Wilsons Promontory Islands Important Bird Area, identified as such by BirdLife International because of its importance for breeding seabirds.[19]

Tidal River is the main river in Wilsons Promontory. The river runs into Norman Bay and swells with the tide. The river is a very fascinating colour, a purple-yellow. This is due to the large number of tea trees in the location, which stain the water with tannin, giving it a tea-like appearance. Darby River is the second major river, with extensive alluvial flats and meanders. It was the site of the original park entrance and accommodation area from 1909 to the Second World War.[20]

Wilsons Promontory is home to many marsupials, native birds and other creatures. One of the most common marsupials found on the promontory is the common wombat, which can be found in much of the park (especially around campsites where it has been known to invade tents searching for food). The peninsula is also home to kangaroos, snakes, wallabies, koalas, long-nosed potoroos, white-footed dunnarts, broad-toothed rats, feather-tailed gliders and emus. Some of the most common birds found on the promontory include crimson rosellas, yellow-tailed black cockatoos and superb fairywrens. There are also many pests, including hog deer, foxes, feral cats, rabbits, common starlings, and common blackbirds.

As the Wilsons Promontory Marine National Park and Corner Inlet Marine National Park have been established, the area holds a variety of marine life and coral reefs. In recent years, after a long disappearance, due to illegal hunting by the Soviet Union with help by Japan, Southern right whales started to return to the area to rest and calve in the sheltered bays along with Humpback whales. Killer whales are also known to pass the area, and dolphins, seals, sea lions, and penguins still occur today.

The peninsula is also home to two large sets of dunes, the Big Drift and Little Drift. They are not very well-known but sometimes visited by hikers and suitable for sandboarding.[21]

Climate

editWilsons Promontory has an oceanic climate heavily influenced by the Roaring Forties, bringing summer temps far below what is the norm on mainland Australia at sea level. Winters and springs are dominated by low-pressure systems and high rainfall.

| Climate data for Wilsons Promontory Lighthouse (39.13° S, 146.42° E) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 41.4 (106.5) |

42.0 (107.6) |

36.9 (98.4) |

32.2 (90.0) |

25.7 (78.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

37.1 (98.8) |

42.0 (107.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 20.3 (68.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

14.2 (57.6) |

15.8 (60.4) |

17.2 (63.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

14.1 (57.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

11.2 (52.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

3.3 (37.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.6 (33.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

2.3 (36.1) |

1.7 (35.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 50.7 (2.00) |

46.4 (1.83) |

69.6 (2.74) |

85.2 (3.35) |

112.6 (4.43) |

119.5 (4.70) |

122.1 (4.81) |

120.9 (4.76) |

98.5 (3.88) |

92.2 (3.63) |

71.6 (2.82) |

63.7 (2.51) |

1,052.6 (41.44) |

| Average precipitation days | 9.8 | 8.9 | 11.8 | 14.8 | 17.7 | 18.8 | 19.3 | 19.4 | 17.6 | 16.0 | 13.3 | 11.8 | 179.2 |

| Source: The Bureau of Meteorology[22] | |||||||||||||

Gallery

edit-

Emus

-

Five Mile Beach

-

Five Mile Beach Camp

-

Beach near Johnny Souey Cove, home to many crabs.

-

Southeast Point.

-

Squeaky Beach

-

The Independent Companies Memorial at Tidal River

-

Whiskey Beach

-

Tidal River seen from Mt Oberon.

-

Southeast tip and lighthouse.

-

Lighthouse and cabin accommodation.

-

Granite rocks.

-

Waterloo Bay.

-

Wombat

-

Rocks at Waterloo Bay.

-

Hiking track to the southeast.

-

Oberon Beach.

-

Mt Oberon, seen from Oberon Beach.

-

Norman Beach, near Tidal River.

References

edit- ^ "Wilsons Promontory". Gazetteer of Australia. Geoscience Australia. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

- ^ "Wilsons Promontory History". www.aussiemap.net. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Wilsons Promontory". The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 February 2004. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Wamoon, Yiruk, Woomom". Wilsons Promontory National Park. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ "Wilsons Promontory Legend". www.aussiemap.net. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ a b Flinders, Matthew (1814). A Voyage to Terra Australis. Vol. 1. Pall Mall: G & W Nicoll.

- ^ Scott, Ernest (1914). The Life of Matthew Flinders. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

- ^ Karen Townrow, An archaeological survey of sealing & whaling sites in Victoria, Heritage Victoria & Australian Heritage Commission, Melbourne, 1997, p. 17.

- ^ Townrow, p. 17.

- ^ a b Horne, Julia (2005). The Pursuit of Wonder: How Australia's Landscape was Explored, Nature Discovered and Tourism Unleashed. Carlton: The Miegunyah Press. p. 148. ISBN 0 522 851665.

- ^ "Wilsons Promontory National Park". Parks Victoria. Government of Victoria. 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ Carbonell, Rachel (4 April 2005). "Back-burning devastates Wilson's Promontory". The World Today (transcript). Australia: ABC Local Radio. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ Ham, Larissa (27 February 2009). "Firefighters continue to battle Wilsons Prom blaze". The Age. Melbourne.

- ^ "Wilsons Promontory to reopen this weekend". The Age. Melbourne. 18 March 2009.

- ^ "Wilsons Promontory after the bushfires". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ "Southern Prom overnight hikes". Parks Victoria. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Preserving the Prom". ABC Australia. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Fishburn, Matthew (July 2023). "Thomas Wilson Esq and the natural history collections of First Fleet Surgeon John White". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 109 (1): 79–109. ISSN 0035-8762. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ^ "IBA: Wilsons Promontory Islands". Birdata. Birds Australia. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Garnet, J. Roslyn, (with additional chapters by Terry Synan and Daniel Catrice) A History of Wilsons Promontory, Published by the Victorian National Parks Association

- ^ "Wilsons Promontory's Big Drift: the Hidden Sand Dunes near Melbourne". Sand-boarding.com. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Climate Statistics for Wilsons Promontory, VIC". Retrieved 11 February 2012.