High Wycombe, often referred to as Wycombe (/ˈwɪkəm/ WIK-əm),[2] is a market town in Buckinghamshire, England. Lying in the valley of the River Wye surrounded by the Chiltern Hills, it is 29 miles (47 km) west-northwest of Charing Cross in London, 13 miles (21 km) south-southeast of Aylesbury, 23 miles (37 km) southeast of Oxford, 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Reading and 8 miles (13 km) north of Maidenhead.

| High Wycombe | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

High Wycombe Guildhall, located at the end of the High Street | |

Coat of arms of High Wycombe. Motto: Industria ditat (Industry enriches) | |

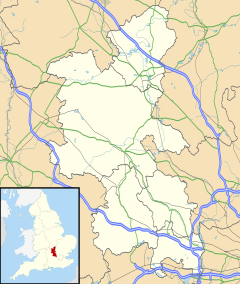

Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Population | 75,814 [1] |

| OS grid reference | SU867929 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | HIGH WYCOMBE |

| Postcode district | HP10-15 |

| Dialling code | 01494 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | www |

According to the 2021 United Kingdom census, High Wycombe's built up area has a population of 127,856, making it the largest town in the ceremonial county of Buckinghamshire. The High Wycombe Urban Area, the conurbation of which the town is the largest component, has a population of 140,684. Part of the urban area constitutes the civil parish of Chepping Wycombe, which had a population of 14,455 according to the 2001 census – this parish represents that part of the ancient parish of Chepping Wycombe which was outside the former municipal borough of Wycombe. There has been a market held in the High Street since at least the Middle Ages. The market is currently held on Tuesday, Friday and Saturday.[3]

History

editEarly history

editThe town once featured a Roman villa (built 150–170 AD)[4] which has been excavated four times, most recently in 2002. Mosaics and a bathhouse were unearthed at the site on what is now the Rye parkland. The name Wycombe would appear to come from the river Wye and the old English word for a wooded valley, "combe", but according to the Oxford English Dictionary of Place-Names the name, which was first recorded in 799–802 as "Wichama", is more likely to be Old English "wic" and the plural of Old English "ham", and probably means "dwellings"; the name of the river was a late back-formation.[5] Wycombe appears in the Domesday Book of 1086 and was noted for having six mills.

The existence of a settlement at High Wycombe was first documented as 'Wicumun' in 970. The parish church was consecrated by Wulfstan, the visiting Bishop of Worcester, in 1086. The town was described as a borough from at least the 1180s, and built its first moot hall in 1226, with a market hall being built later in 1476.[6]

The 1841 census reports the population that year was 3,184.[7]

Trade and industrial development

editHigh Wycombe remained a mill town through Medieval and Tudor times, manufacturing lace and linen cloth. It was also a stopping point on the way from Oxford to London, with many travellers staying in the town's taverns and inns.[6]

The paper industry was notable in 17th and 18th century High Wycombe. The Wye's waters were rich in chalk, and therefore ideal for bleaching pulp. The paper industry was soon overtaken by the cloth industry.

Wycombe's most famous industry, furniture (particularly Windsor chairs) took hold in the 19th century, with furniture factories setting up all over the town.[8] Many terraced workers' houses were built to the east and west of town to accommodate those working in the furniture factories. In 1875, it was estimated that there were 4,700 chairs made per day in High Wycombe. When Queen Victoria visited the town in 1877, the council organised an arch of chairs to be erected over the High Street, with the words "Long live the Queen" printed boldly across the arch for the Queen to pass under. Wycombe Museum includes many examples of locally made chairs and information on the local furniture and lace industries.

The town's population grew from 13,000 residents in 1881 to 29,000 in 1928. Wycombe was completely dominated socially and economically by the furniture industry.

20th century

editBy the 1920s, many of the housing areas of Wycombe had decayed into slums. A slum clearance scheme was initiated by the council in 1932, whereby many areas were completely demolished and the residents rehoused in new estates that sprawled above the town on the valley slopes.[9] Some of the districts demolished were truly decrepit, such as Newland, where most of the houses were condemned as unfit for human habitation. However, some areas such as St. Mary's Street contained beautiful old buildings with fine examples of 18th and 19th century architecture.[10]

From 1940 to 1968 High Wycombe was the seat of the RAF Bomber Command. Moreover, during the Second World War, from May 1942 to July 1945, the U.S. Army Air Force's 8th Air Force Bomber Command, codenamed "Pinetree", was based at a former girls' school at High Wycombe. This formally became Headquarters, 8th Air Force, on 22 February 1944.[11]

In the 1960s the town centre was redeveloped and many old buildings were demolished. The River Wye was culverted under concrete between 1965 and 1967 from and demolishing most of the old buildings in Wycombe's town centre. Two shopping centres were built (the Octagon in 1970 and the Chilterns' in the 1980s) along with many new multi-storey car parks, office blocks, flyovers and roundabouts.

Modern-day High Wycombe

editHigh Wycombe comprises a number of suburbs including Booker, Bowerdean, Castlefield, Cressex, Daws Hill, Green Street, Holmers Farm, Micklefield, Sands, Terriers, Totteridge, Downley and Wycombe Marsh, as well as some nearby villages: Hazlemere and Tylers Green. Particular areas in the suburbs of Castlefield, Micklefield, Terriers and Totteridge have high levels of deprivation compared to the rest of the urban area.

Although situated in the county of Buckinghamshire, which is one of the most affluent parts of the country,[12] Wycombe contains some considerably deprived areas.[13] In 2007, a GMB Union survey ranked the Wycombe district as the 4th dirtiest in the South East and the 26th dirtiest in the whole UK.[14][15] The survey found litter on 28.5% of streets and highways. Data for the survey were taken from the Government's 2005/06 Audit Commission.

The town has undergone major redevelopment, including development of the town's existing shopping centre, completion of the Eden Shopping centre, and redevelopment of the Buckinghamshire New University with a large student village and new building on Queen Alexandra Road.[16]

These developments prompted the building of larger blocks of flats, a multimillion-pound hotel in the centre, and a Sainsbury's store on the Oxford road next to the Eden shopping centre and bus station.

Climate

edit| Climate data for RAF High Wycombe (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.1 (44.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

1.7 (35.1) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 82.5 (3.25) |

59.7 (2.35) |

51.2 (2.02) |

56.9 (2.24) |

64.6 (2.54) |

57.8 (2.28) |

54.0 (2.13) |

69.6 (2.74) |

64.2 (2.53) |

84.6 (3.33) |

90.6 (3.57) |

81.6 (3.21) |

817.3 (32.18) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 13.2 | 11.3 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 9.9 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 12.0 | 13.5 | 13.0 | 131.3 |

| Source: Met Office[17] | |||||||||||||

Demography

editHigh Wycombe's population figure differs with the varying definitions of the town's area. That of the town not including its suburbs was 77,178. However, Hazlemere is now regarded as part of Wycombe, which makes the population of High Wycombe town 92,300. The High Wycombe urban area (the town with some surrounding settlements) had a population of 133,204.[18] This is an increase of 13% since the 2001 population of 118,229.[19]

| Place | Population (2001 census) | Population (2011 census) |

| Bourne End/Flackwell Heath | 12,795 | |

| Cookham | 5,304 | 5,108 |

| Great Kingshill | 2,452 | 1,761 |

| Hazlemere/Tylers Green | 20,500 | |

| High Wycombe | 77,178 | 120,256 |

| Walters Ash | 3,853 | |

| Hughenden Valley | 1,915 | |

| TOTAL | 118,229 | 133,204 |

Notes:

- Hazlemere/Tylers Green and Bourne End/Flackwell Heath were included as part of the High Wycombe subdivision in the 2011 census.

- Hughenden Valley and Walters Ash were separate urban areas in the 2001 census.

- The Walters Ash subdivision includes the village of Naphill.

According to the 2011 census, the parliamentary constituency of Wycombe consists of approximately 108,000 people.[20] White British people comprised 67.2% of the constituency's population. The next largest group in the constituency were Pakistanis, who comprised 11.8% of the population.[20] 52.3% of the population were Christians, 24% were no religion and 13.4% were Muslim.[20] Wycombe is home to the largest population of Vincentians in the United Kingdom.[21]

65.7% of the constituency owned their own home either outright or with a mortgage. 14.6% were social renters and 17% were private renters.[20] 15.8% of households in the constituency did not own an automobile.[20]

Governance

editParliamentary constituency

editWycombe's political history extends back to 1295. The Wycombe Constituency had continuously elected Conservative Members of Parliament since 1951 until the Labour Party was voted in during the May 2024 general election.

High Wycombe has been home to two Prime Ministers:

- William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne, who lived at what is now Wycombe Abbey and was MP for the town.

- Benjamin Disraeli, who lived at nearby Hughenden Manor, was defeated as a Radical candidate for the seat three times in the 1830s but won election in 1868 and 1874–1876 as a Conservative. Disraeli made his first political speech in Wycombe, from the portico over the door of the Red Lion Hotel at 9–10 High Street.[22]

High Wycombe was also in the constituency represented by John Hampden (1594-1643), a leading MP and Parliamentarian commander who was killed in action during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

The town is represented by Labour MP Emma Reynolds.

The town until the 4th July 2024 General Election was represented by Conservative MP Steve Baker. He was chairman of the eurosceptic European Research Group and was a junior minister in the Department for Exiting the European Union from 2017 to 2018. In July 2018, Baker resigned alongside Brexit Secretary David Davis and Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson in opposition to the Chequers plan proposed by Prime Minister Theresa May.

Local government

editSince 2020, there has only been one tier of local government covering High Wycombe, being the unitary authority of Buckinghamshire Council. The former High Wycombe Borough Council was abolished in 1974. Instead of a town council, the councillors elected to Buckinghamshire Council to represent the unparished part of High Wycombe also act as charter trustees, meeting to choose the town's mayor.[23]

| High Wycombe Chepping Wycombe (until 1946) | |

|---|---|

| Ancient Borough (before 1237–1835) Municipal Borough (1836–1974) | |

| Population | |

| • 1891[24] | 13,435 |

| • 1971[25] | 58,445 |

| History | |

| • Created | before 1237 (Ancient Borough) 1 January 1836 (Municipal Borough) |

| • Abolished | 31 March 1974 |

| • Succeeded by | Wycombe District |

| • HQ | High Wycombe |

| Contained within | |

| • County Council | Buckinghamshire |

The ancient parish of Chepping Wycombe covered both the town of High Wycombe and a large rural area around it. To distinguish it from the neighbouring parish of West Wycombe, the parish was historically known variously as East Wycombe, Great Wycombe, High Wycombe, Much Wiccomb,[26] Chipping,[26] Chipping Wycombe, or Chepping Wycombe. The latter version eventually became the official name of parish, despite the town itself being more usually known as High Wycombe. The town does not appear to have been a borough at the time of the Domesday Book in 1086, but was being described as a borough by the 1180s. In the 1220s and 1230s there were disputes with the lord of the manor, Alan Basset, as to the extent of the town's independence. These disputes were settled in favour of the town, with its borough rights being confirmed in 1237. Charters confirming the town's borough status were subsequently issued on a number of occasions.[27] As part of the general overhaul of ancient boroughs across the country under the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, the town became a municipal borough on 1 January 1836, under the name of Chepping Wycombe.[28]

The borough only covered the built-up area of the town, rather than the whole parish. The borough council was therefore responsible for the secular elements of local government within its area, whereas the Chepping Wycombe parish vestry was responsible for secular matters in the part of the parish outside the borough, whilst being responsible for ecclesiastical matters across the whole parish, including the borough. In 1866, under the Poor Law Amendment Act 1866, the old parish of Chepping Wycombe was split into two civil parishes: one called "Wycombe" or "Wycombe Borough" which covered the area of Chepping Wycombe municipal borough, and another parish which retained the name "Chepping Wycombe" which covered the rural parts of the old parish outside the borough.[29]

By that time, the urban area was starting to expand beyond the old borough boundaries into the newly separated parish of Chepping Wycombe, particularly in the Wycombe Marsh area. To deal with growing urbanisation in its area, the parish of Chepping Wycombe was declared to be a local government district in 1868, governed by a local board.[30][31] The situation was partially simplified in 1880 when the local board was abolished and the borough boundaries were extended to cover the more built-up parts of Chepping Wycombe parish. The parish boundaries were not changed at the same time to match, making the Chepping Wycombe Borough Council responsible for all of the Wycombe parish area and part of the Chepping Wycombe parish area.[32]

When parish and district councils were established under the Local Government Act 1894, it was stipulated that parishes could not straddle district boundaries. The Chepping Wycombe parish was therefore split again in December 1894, with the part within the borough becoming "Chepping Wycombe Urban" and the part outside it becoming "Chepping Wycombe Rural". Chepping Wycombe Rural was placed in the Wycombe Rural District, whilst the Chepping Wycombe Municipal Borough covered the two parishes of Wycombe and Chepping Wycombe Urban. The two parishes within the borough merged on 30 September 1896 to form a single parish called High Wycombe, although the official name of the borough council which governed that parish remained "Chepping Wycombe Borough Council" until 1 August 1946, when it changed its name to "High Wycombe Borough Council".[33][34][35] The surrounding Chepping Wycombe Rural parish changed its name to Chepping Wycombe parish in 1949.

From 1757 until 1932 the borough council met at the Guildhall. The council built Town Hall on Queen Victoria Road in 1904 as a public assembly hall and entertainment venue, with the intention of later extending it to also serve as council offices and meeting place, but the extension was never built. Instead, the council built the Municipal Offices on Queen Victoria Road in 1932, which then acted as its meeting place and offices until the council's abolition in 1974.[36]

From 1974 to 2020, High Wycombe formed part of Wycombe District, with its council being based at the former borough council's Municipal Offices (renamed District Council Offices) on Queen Victoria Road. Following further local government reorganisation in 2020 Wycombe District was abolished to become part of Buckinghamshire Council.

Weighing the mayor

editA ceremony carried out in the town since 1678[37] involves the weighing of the mayor. At the beginning and end of each year of service, the mayor is weighed in full view of the public to see whether or not he or she has gained weight, presumably at the taxpayers' expense. The custom, which has survived to the present day, employs the same weighing apparatus used since the 19th century. When the result is known, the town crier announces "And no more!" if the mayor has not gained weight or "And some more!" if they have. Their actual weight is not declared.[38]

Education

editBuckinghamshire is one of the few counties that still has a selective educational system based on the former tripartite system. Pupils in their last year at primary school take what is commonly known as the 11+ exam. Their score in this exam determines whether they are accepted into a grammar school or a secondary modern school.

Primary schools

editCatchment area primary schools in High Wycombe[39]

- Ash Hill Combined School

- Beechview Junior School

- Booker Hill Combined School

- Castlefield Combined School

- Chepping View Combined School

- Hamilton Academy

- Hannah Ball School

- Highworth Combined School & Nursery

- High Wycombe Church of England Combined School

- Kings Wood Combined School

- Marsh Infants School

- Millbrook Combined School

- Oakridge Combined School

- St Michael's Catholic School (combined primary and secondary school)

- The Disraeli Combined School and Children's Centre

- West Wycombe Combined School

Secondary schools

edit- Cressex Community School

- Highcrest Academy

- John Hampden Grammar School

- St Michael's Catholic School (combined primary and secondary school)

- Royal Grammar School

- Wycombe High School

- Sir William Ramsay School

- Holmer Green Senior School

Independent schools

edit- Crown House School[40]

- Godstowe Preparatory School

- Pipers Corner School

- Wycombe Abbey

- Wycombe Preparatory School

Further and higher education

editBuckinghamshire College Group is a further education college located near High Wycombe at Flackwell Heath, with campuses also at Aylesbury and Amersham. High Wycombe is home to the main campus of Buckinghamshire New University. It is located in the centre of the town on the former site of the High Wycombe College of Art and Technology. It received its university charter in summer 2007.

Media coverage

editHigh Wycombe has been featured in the national media in recent years for a number of different reasons, including seasonal coverage of the local library's refusal to display a Christmas carol service poster[41] and other stories such as the triple shooting[42] of three young Asian men, a small-scale riot between feuding families and gangs in which knives, metal poles, and an axe were used[43] whilst a gunman sprayed bullets; and the shooting and murder of Natasha Derby at point-blank range in the middle of a busy dance floor at a town centre venue.[44][45]

The town appeared in national and international media after anti-terrorism raids were carried out across the town on 10 August 2006 as part of the 2006 transatlantic aircraft plot.[46] Five arrests were made at three different houses in the town's Totteridge and Micklefield areas. A small number of houses in High Wycombe were evacuated in Walton Drive, which is thought to be because one of the raided houses contained dangerous liquid chemicals.

A three miles (five kilometres) no-flight zone over the town was ordered. Other raids and arrests were also made in East London and Birmingham.

King's Wood to the north of the town was cordoned off for four months to be searched by police, and many suspicious items were allegedly found including explosives, detonators, weapons and hate tapes. Other woodlands in the Booker area of the town and the M40 at High Wycombe as well as nearby woods were also under observation. Explosives officers were called to the motorway, as were forensic officers. A lane of the motorway was closed as a precaution.

On 21 December 2009, heavy snowfall hit the town, paralysing its road network (which is mainly on steep hills), and causing major disruption to refuse services for several weeks. Staff and customers of the John Lewis department store were stranded overnight, leading to national news reports and interviews from GMTV and other radio stations on the morning of 22 December.[47]

Notable residents (past and present)

editEntertainment and the media

edit- Colin Baker – actor who played the sixth incarnation of the Doctor in Doctor Who, and columnist for the Bucks Free Press.[48]

- Mighty Boosh stars Noel Fielding and Dave Brown met when they attended Bucks New University in Wycombe. Julian Barratt then joined the group after Fielding scouted him performing in the Wycombe Swan theatre.[49]

- Charlotte Bray, composer was brought up in High Wycombe

- Jimmy Carr - (born 1972), comedian, presenter, writer and actor. Grew up in Farnham Common and attended the Royal Grammar School in High Wycombe.

- James Corden (born 1978), English comic actor, writer, and television personality. Grew up in Hazlemere and attended multiple schools in the area

- Theo James (born 1984), actor

- Ian Stanley (born 1957), Keyboardist, Songwriter, Producer, Original Keyboardist for Tears for Fears

- Howard Jones (born 1955), musician

- Aaron Taylor-Johnson (born 1990), actor

- Anna Lapwood (born 1995), organist and choir director

- Leigh-Anne Pinnock (born 1991), singer, songwriter and actress

- Terry Pratchett (1948–2015), worked as a journalist at the Bucks Free Press.[50]

- Laura Sadler (1980-2003), actress

Sports

edit- Elliot Benyon – footballer with Hanwell Town.[51]

- Dominic Blizzard – former footballer, most recently with Plymouth Argyle.

- Simon Church – retired footballer, most recently with Plymouth Argyle, also represented Wales internationally.[52]

- Ross Gunn - motor-racing driver, currently racing in the IMSA sportscar championship.

- Matt Dawson – retired rugby player, scrum-half for the England rugby union team which won the Rugby World Cup in 2003. Educated at the Royal Grammar School.[53]

- Luke Donald – former world no.1 golfer, educated at the Royal Grammar School.[54]

- Jack Goff – motor-racing driver, currently racing in the British Touring Car Championship.[55]

- Isa Guha – former cricketer, Women's World Cup winner with England.[56]

- Jean Hawes – former hockey player who received an MBE in 2007.[57]

- Tom Ingram – motor-racing driver, currently racing in the British Touring Car Championship.[58]

- Matt Ingram – footballer with Hull City, formerly with Wycombe Wanderers.[59]

- Mike Keen – former footballer and manager, winner of the 1966–67 Football League Cup with Queens Park Rangers.[60]

- Robbie Kerr – motor-racing driver, most recently in the A1 Grand Prix.[61]

- Phil Newport – former Worcestershire and England cricketer.[62]

- Tom Rees – former England and Wasps Rugby Flanker. Educated at the Royal Grammar School.[63]

- Nicola Sanders – former track and field athlete, Olympic bronze medal winner.[64]

- Wilf Slack – former Middlesex and England cricketer.[65]

- Christian Wade – former Wasps player, former Buffalo Bills American football player, now playing for Racing 92. Educated at the Royal Grammar School.[66]

Other fields

edit- Heston Blumenthal – celebrity chef and owner of the Michelin 3-star Fat Duck restaurant. He was educated at John Hampden Grammar School.[67][68]

- Mitford family – aristocrats.[69]

- Roger Scruton – philosopher, educated at the Royal Grammar School.

- Geoffrey De Havilland – aviation pioneer and aircraft engineer. Born at Terriers House.[70]

- Benjamin Disraeli – 19th century prime minister, politician, and literary figure.[71]

- Eric Gill – sculptor and print maker.[72]

- Karl Popper – philosopher.[73]

- Jean Shrimpton – supermodel.[74]

- Frances Dove - Women's campaigner and Educator.[75]

Local media

editTelevision signals are received from the Crystal Palace and local relay transmitters, placing High Wycombe in the BBC London and ITV London areas. [76][77]

Local radio stations are BBC Three Counties Radio on 98.0 FM and community radio stations such as Awaaz Radio on 107.4 FM and Wycombe Sound on 106.6 FM.

The Bucks Free Press is the town local newspaper. [78]

Transport

editRoad

editThe town's nearest motorway is the M40, which has two junctions serving Wycombe: junction 3 for Loudwater and High Wycombe (east) and junction 4 at Handy Cross roundabout for central Wycombe, Marlow and Maidenhead. Junction 4 is a major interchange between the M40 and A404 trunk road which provides a link to the M4. It had suffered from heavy congestion but was improved by the Highways Agency in 2006.[79] Junction 3 is restricted; only traffic going towards and coming from London can join and exit respectively. The M25 and M4 are also fairly close.

Other roads include the A404 towards Marlow and Amersham; the A4010 towards Aylesbury; and the A40 towards Beaconsfield and Oxford.

Bus

editHigh Wycombe Eden bus station is served by Redline Buses and Carousel Buses. Major destinations include Reading, Slough, Aylesbury, Heathrow Airport, Maidenhead, Amersham, Chesham, Uxbridge, Beaconsfield Gerrards Cross and Hemel Hempstead. In November 2013, First Berkshire & The Thames Valley added express route X9 to Maidenhead to its existing X74 express to Slough.[80] Other operators serving the town include Red Eagle, Red Rose and Z&S Buses.

The town also has a Park and Ride facility located in Cressex, near junction 4 of the M40. Services run to the town centre, passing the railway station, High Wycombe Coachway which is served by coach services such as: the Airline, Harlequin Travel, Countryside Coaches and Apple Travel which go to places like Maidenhead, Oxford, Heathrow Airport, Gatwick Airport and Farnham .[81]

Coach

editAs of January 2022, no National Express coaches have entered High Wycombe Town centre. The Airline, operated by Oxford Bus Company, operates coach services from Oxford to Heathrow and Gatwick airports via Handy Cross Hub.[82]

Rail

editThe town is served by High Wycombe railway station on the Chiltern Main Line, with services operated by Chiltern Railways from London Marylebone to Aylesbury, Oxford, Stratford-upon-Avon, Birmingham Snow Hill and Kidderminster.[83][84] The station is the busiest in South Buckinghamshire. Express services travel to London in 23 minutes, slower trains take up to 45 minutes.

The Wycombe Railway ran from High Wycombe to Maidenhead on the Great Western Main Line through Loudwater and Bourne End. However, it was a victim of the Beeching cuts with the Wycombe to Bourne End section closed in May 1970. The southern section remains open as part of the Marlow Branch Line.[85]

Air

editHeathrow Airport is the nearest international airport, located just outside Buckinghamshire in Hillingdon. Wycombe Air Park on the southern edge of the town is popular with learning pilots and gliders.

Facilities and places of interest

editThere are two shopping centres: the Eden Centre which spreads from the High Street under the Abbey Way flyover to the south of the A40; and the Chilterns Centre, which is located between Queen's Square and Frogmoor to the north. The High Street (pedestrianised in the early 1990s) has a number of 18th and 19th century buildings, and ends at the colonnaded Guildhall that was built in 1757 by Henry Keene, funded by the Earl of Shelburne, and renovated in 1859.[86] The small octagonal-shaped Cornmarket opposite, known locally as the Pepper Pot, was rebuilt to designs by Robert Adam in 1761. The large parish church of All Saints[87] was founded in 1086, enlarged in the 18th century and extensively restored in 1889. There is a large, well equipped theatre, the Wycombe Swan, which hosts many acts and shows before or after their appearance in the West End.

In April 2008, a new development of the town centre was completed. This included the demolition and movement of the bus station and the brand new Eden Shopping Centre, with 107 shops, new restaurants, a large bowling alley and cinema and new housing. The old Octagon shopping centre was connected to the new development. The complex, one of the largest in the country, is seen as a major milestone in the regeneration of the town.

To the east of the town centre is the extensive Rye park (and river) and dyke. The park had an outdoor swimming pool, which closed in 2009. The pool has now reopened together with a new gym and has been renamed as the Rye Lido.[88] The River Wye winds through the green space, which is particularly attractive during the summer. Wycombe's yearly "Asian Mela" takes place on the Rye. There is a museum on Priory Avenue in the town centre situated on its own grounds and including a Norman castle mound. The theme of the museum is the history of Wycombe, with the main focus being the chair industry.

Wycombe town centre is home to many public houses and bars, especially in the Frogmoor area. The White Horse pub appeared on 'Britain's toughest pubs'.[89]

The town features the old Wycombe Summit,[90] formerly the largest dry ski slope in England, before it was destroyed in a fire. Construction work was due to start in September 2008, on what would have become England's third and largest indoor real snow ski centre. In May 2009, it was announced that construction would be delayed due to 'difficulties getting a planning consent amendment.'[90] As of 31 January 2012 it was announced that the site was up for sale.[91]

Hughenden Manor borders the northern urban fringe of High Wycombe, approximately two miles (three kilometres) from the centre of town. Built in the Regency period, the architecturally appealing house was also home to Benjamin Disraeli for three decades in the mid-19th century. The three-floor mansion is situated in its own extensive grounds with beautifully landscaped gardens which back into the attractive Chiltern countryside. It is open to the public all year round as an historical attraction.

The local council maintains a landmark statue of a red lion above the former Woolworth's store on the High Street. Its significance dates back to when the building was the Red Lion Hotel. Since its installation, the lion has been replaced several times and has had to undergo extensive repair due to damage from both the elements and human interference. Another notable landmark is the ruins of the Hospital of St John the Baptist,[92] which is located on Easton Street, just east of the town centre opposite the Rye parkland, and dates to the 12th century. The stone structure is one of the very oldest in Wycombe, and is said to contain stone used from the Roman villa on the Rye.

The site of the ancient Desborough Castle is situated between the Desborough and Castlefield suburbs of the town, and provides their names.

Industry

editWycombe was once renowned for chairmaking (the town's football team is nicknamed the 'Chairboys') and furniture design remains an important element of the town's university curriculum, Buckinghamshire New University. Among the best known furniture companies were Ercol and E Gomme. The River Wye runs through the valley, where beech trees were cut down by the chair industry to forming the town centre (circa 1700), with housing along the slopes (some areas are still surrounded by woods). The town was also home to the worldwide postage stamp and banknote printer Harrison and Sons. More recent industries in the town include the production of paper, precision instruments, clothing and plastics. Many of these are situated in an industrial area of the Cressex district, southwest of the town centre. The two largest sites belong to the companies Swan (tobacco papers, filters and matches) and Verco (office furniture), who until 2004 sponsored the local football team, Wycombe Wanderers.

Wycombe's industrial past is reflected on the town's motto Industria ditat, "Industry enriches".[93] The motto can be found on town crest and Mayor's badge of office.[94]

Local attractions

editRecreation

editAviation

editBooker Gliding Club and two flying schools are based at Wycombe Air Park, the modern name for Booker Airfield, to the south of the M40 motorway on the western edge of the town. Many of the replica aircraft used in the film industry, for example in films such as Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines, Aces High and The Blue Max were built and flown from there. Wycombe Air Park is one of the busiest general aviation airfields in the UK. The Air Park is also home to Buckinghamshire Squash and Racketball Club.

Leisure

editHollywell Mead, an open swimming pool site in the town's Rye Park, closed in March 2009 due to high running costs[95] and was mothballed.[96] However, in summer 2012, after a £2 million investment into the site, a new sports & leisure facility was reopened.[88] Further redevelopment works later took place, with improved tennis courts reopening in late 2013[97] and an upgraded pool reopening in May 2016.[98]

There is a large leisure centre to the south of town at the top of Marlow Hill, close to the Handy Cross roundabout. Many sporting activities take place here and there is an Olympic-size swimming pool.[99][100] The original leisure centre was designed by renowned architect John Attenborough, and opened in 1975.[101] In 2011, proposals were made for a new leisure centre to be constructed on the site of the existing running track, with the relocation of the existing artificial turf pitch to the nearby John Hampden Grammar School and the running track to Little Marlow.[102]

In January 2014, the artificial turf pitch had been relocated.[103] By May 2014, construction work on the new facility had commenced.[104] The old leisure centre closed in December 2015,[101] with the new leisure centre opening in January 2016.[105] The old leisure centre was later demolished to make way for other developments.[106]

Housing

editA new experimental scheme to knock down old council flats in Micklefield and replace them with housing association properties was approved by John Prescott in 2003 after overwhelming approval by council residents. There are many different housing areas within the town, some of which such as the Castlefield district have gained a bad reputation for crime and drug-related problems.

The town is a diverse mixture of large council estates built in the 1930s, 1950s and 1960s that sprawl up the valley sides, compact Victorian terraces in the bottom of the valley to the east and west of town, and desirable areas for wealthy commuters. The Amersham Hill area is noted for its large period properties and leafy streets. Recent developments are showing a tendency towards blocks of flats, and developers are mainly making use of brownfield sites.

Sport

editFootball

editThe town's football team, Wycombe Wanderers, founded in 1887, play at Adams Park, named after Frank Adams who donated the old Loakes Park ground to the club.[107] They relocated to their current stadium in 1990. They currently play in EFL League One and have been members of the English Football League since 1993 when they were promoted as champions of the 1992–93 Football Conference. Since then they have enjoyed two notable cup runs (to the semi-finals of the FA Cup in 2001 and the Football League Cup in 2007), and four recent promotions from the fourth tier of the English league to the third tier (via the playoffs in 1994, and automatically in 2009, 2011 and 2018), plus promotion from the third tier to the second tier (Championship) via the playoffs in 2020. They have been managed by a number of high-profile football figures, including Martin O'Neill, Lawrie Sanchez, Tony Adams, and Gareth Ainsworth. Their current manager is former player Matt Bloomfield.

Rugby

editThe Wasps rugby union team also played at Adams Park for home games between the 2002–03 season and December 2014, the club's most successful spell.[108]

Cricket

editHigh Wycombe Cricket Club is an English amateur cricket club with a history of cricket in the village dating back to 1823.[109] The club has a significant success record, with 9 Home Counties Premier Cricket League championship titles to their name.[110] High Wycombe field five senior teams. The 1st team play in the Home Counties Premier Cricket League (a designated ECB Premier League[110]) and the rest compete in the Thames Valley Cricket League.[111] They also have an established junior training section that play competitive cricket in the Bucks Cricket Competitions league.[112]

Closest cities, towns and villages

editAmersham (7 mi or 11 km), Aylesbury (17 mi or 27 km), Beaconsfield (5 mi or 8 km), Marlow (4 mi or 6 km), Maidenhead (9 mi or 14 km), Oxford (26 mi or 42 km), Reading (23 mi or 37 km)

Twin towns

editHigh Wycombe is twinned with:

- Kelkheim, Germany

In popular culture

editHigh Wycombe is sometimes portrayed as a rather dull town where nothing much happens,[113] as in this exchange between Kenneth Horne and Kenneth Williams in Round the Horne:

KH: What _did_ you do in the war, Ken?

KW: I drove a bus in High Wycombe. They used to call us "The Ladies from Hell".

The town was mentioned several times in series 4 episode 2 (The Lying Detective) of the BBC TV series Sherlock, much in the same key.[114]

Scenes in series 2 episode 3 (The Waldo Moment) of the Channel 4 TV series Black Mirror were filmed in High Wycombe.[115]

References

edit- ^ "Community Board Profile: High Wycombe" (PDF). Buckinghamshire Public Health. Buckinghamshire Council. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ "High Wycombe". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ "High Wycombe". High Wycombe - Visit Buckinghamshire.

- ^ "Brief history of High Wycombe". Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ Eilert Ekwall, 1960. The Concise Oxford English Dictionary of Place-Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198691033.

- ^ a b "High Wycombe : Historic Town Assessment Report Draft" (PDF). Buckscc.gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge Vol.III, London, 1847, Charles Knight, p.899

- ^ "High Wycombe Furniture Trade History". 16 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Beauman, Nicola (2009). The Other Elizabeth Taylor. Persephone. p. 175. ISBN 978-190-646210-9.

- ^ "Timeline History of High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire". Visitoruk.com. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Eighth Air Force". Archived from the original (DOC) on 30 June 2006. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Microsoft Word - Deprivation Fact File Final.doc" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Wycombe shamed in league table of filth (From Bucks Free Press)". Bucksfreepress.co.uk. 20 July 2007. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Accommodation at Bucks New - Buckinghamshire New University". Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ "RAF High Wycombe (Buckinghamshire) UK climate averages - Met Office". Met Office. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "2011 Census - Built-up areas". ONS. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics - Urban areas in England and Wales KS01 Usual resident population released 17 Jun 2004". Ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Census data for Parliamentary constituencies in England & Wales, 2011: Wycombe" (PDF). data.parliament.uk. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Wareham, Stephanie (12 April 2021). "Wycombe MP Steve Baker donates to fund to help St Vincent residents after devastating volcano eruption". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Historic England. "Red Lion Hotel, 9 and 10 High Street (1125159)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ "Mayor Making". Mayor and Charter Trustees of High Wycombe. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ "Chepping Wycombe Urban Sanitary District". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ "High Wycombe Municipal Borough, A Vision of Britain through Time". GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Chipping", Encyclopaedia Britannica, vol. II (1st ed.), Edinburgh: Colin Macfarquhar, 1771.

- ^ Page, William (1925). A History of the County of Buckingham, Volume 3. London: Victoria County History. pp. 112–134. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ Municipal Corporations Act 1835. 1835. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ Youngs, Frederic A. (1979). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, Volume 1: Southern England. London: Royal Historical Society. p. 43.

- ^ "Wycombe: Parish Local Board". Bucks Herald. Aylesbury. 7 March 1868. p. 6. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ "Local Government Act, 1858: Notice of Adoption of Act by the Parish of Chepping Wycombe, in the County of Bucks". London Gazette (23360): 1591. 10 March 1868. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ Chepping Wycombe Borough Extension Act 1880. H.M. Stationery Office. 1880. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ "Bucks County Council: Uniting the parishes of Wycombe". South Bucks Standard. High Wycombe. 14 February 1896. p. 5. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ Annual Report of the Local Government Board. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1897. p. 276. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ Census Report 1951: County Report for Buckinghamshire. General Register Office. 1953. p. 8. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

On 1st August 1946 under Section 5 of the High Wycombe Corporation Act 1946, Chepping Wycombe M.B. was renamed High Wycombe.

- ^ Local Government Act 1972. 1972 c.70. The Stationery Office Ltd. 1997. ISBN 0-10-547072-4.

- ^ Lawrence Dunhill (16 March 2011). "Weights will not be read out at ceremony to save embarrassment". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Roud, Stephen (2006). The English Year: A month-by-month guide to the Nation's customs and festivals from May Day to Mischief Night. Penguin. ISBN 9780140515541. OCLC 70671478.[page needed]

- ^ "A Guide to Primary Catchment Areas for September 2013 in High Wycombe Town" (PDF). Buckscc.gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Crown House Preparatory School High Wycombe". Crownhouseschool.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ Burkeman, Oliver (8 December 2006). "The phoney war on Christmas". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Three held in triple shooting". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Gun police lay siege to house after bloodbath. - Free Online Library". Thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Wild-West style shooting killed Natasha Derby, court hears". Getreading.co.uk. 4 September 2004. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Mother in plea over reggae killer". BBC News. 8 September 2004. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ "'Airlines terror plot' disrupted". BBC News. 10 August 2006.

- ^ "100 customers and staff stranded by snow sleep in John Lewis store". The Daily Telegraph. London. 22 December 2009. Archived from the original on 25 December 2009.

- ^ "Colin's Major role". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ Farr, Simon (10 September 2011). "Noel Fielding talks the formation of The Mighty Boosh during Wycombe student days". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Leat, Paul (10 November 2006). "Terry Pratchett and his first job". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Whitehawk F.C. official matchday programme v Truro City, 20 January 2018

- ^ "Leyton Orient | Simon Church – Profile". Orient.vitalfootball.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ Davies, Gareth A (4 February 2002). "Talking School Sport: RGS High Wycombe revel in succession of scrum-halves". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Feldberg, Alan (1 March 2011). "Wycombe's Luke Donald beats world number one". This is London. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ Gray, Harry (3 May 2016). "Goff targeting first win at Thruxton as BTCC title race goes on". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Isa Guha Player Profile". ICC Women's World Cup. Archived from the original on 10 December 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "Disabled people's chief honoured". BBC News. 16 June 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Home". Tom-ingram.com. 4 June 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "13 Matt Ingram Goalkeeper". hullcitytigers.com. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Murphy, Alex (2 May 2009). "Mike Keen: Footballer who captained Third Division Queen's Park Rangers to League Cup victory in 1967". Independent. London. Archived from the original on 11 February 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Kerr looks to finish the job he started". Crash. 3 May 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ Feldberg, Alan (2 July 2009). "RGS festival underway on Monday". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Tom Rees". Scrum.com. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ Matt Jones. "Colin Jackson's Raise Your Game – Nicola Sanders". BBC. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Middlesex County Cricket Club: Hall of Fame Profiles". Archived from the original on 12 February 2012.

- ^ "RGS Former schooboys". The Royal Grammar school. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017.

- ^ Farr, Simon (4 May 2010). "Chef Heston cooks up a storm in Wycombe". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Lacey, Hester (15 July 2011). "The Inventory: Heston Blumenthal". www.ft.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "The Mitfords were good ol' High Wycombe gals (From This Is Local London)". Thisislocallondon.co.uk. 8 March 2001. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Sports, leisure and tourism". Wycombe.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "National Trust | Hughenden Manor". Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ "Font Designer — Eric Gill". Linotype.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Rafe Champion on Malachi Hacohen, Karl Popper, The Formative Years, 1902–1945". The-rathouse.com. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Sale, Jonathan (28 August 1997). "PASSED/FAILED: Jean Shrimpton". The Independent. London. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32880. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Crystal Palace (Greater London, England) Full Freeview transmitter". May 2004.

- ^ "High Wycombe (Buckinghamshire, England) Freeview Light transmitter". May 2004.

- ^ "Buckinghamshire News, Sport, Events".

- ^ "M40 Junction 4/A404 Handy Cross Junction Improvement". Highways Agency. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- ^ "Notices & Proceedings" (PDF). Office of the Traffic Commissioner. 15 October 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ "Home". High Wycombe Park & Ride. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ "the airline". www.oxfordbus.co.uk. Oxford Bus Company. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ High Wycombe Chiltern Railways

- ^ High Wycombe National Rail Enquiries

- ^ History Marlow - Maidenhead Passengers Association

- ^ Page, William. "Parishes: High Wycombe Pages 112-134 A History of the County of Buckingham: Volume 3. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1925". British History Online. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "All Saints Church, High Wycombe - home". Allsaintshighwycombe.org. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ a b Simon Farr (July 2012). "Council boss hails Wycombe Rye Lido ahead of centre's opening". Bucksfreepress.co.uk. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Pub owner gets tough over story (From This is Local London)". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ a b "WYCOMBE SUMMIT England's longest ski & snowboard centre". Wycombesummit.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ Simon Farr (31 January 2012). "Wycombe Summit 'ski centre' site up for sale (From Bucks Free Press)". Bucksfreepress.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 871.

- ^ Pine, L.G. (1983). A dictionary of mottoes (1 ed.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 113. ISBN 0-7100-9339-X.

- ^ "History of Wycombe's swan « Mayor of High Wycombe". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Phillips, Neil (23 December 2008). "Veteran swimmer pleads for Wycombe's open air pool to stay open". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Farr, Simon (8 April 2009). "Leisure chief says Holywell Mead will not be bulldozed". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Farr, Simon (12 October 2012). "Work to begin on new look sports courts at Rye Lido". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Sheth Trivedi, Shruti (5 May 2016). "Outdoor pool re-opens in time for summer after major improvements". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Wycombe Leisure Centre". www.placesleisure.org. Places Leisure. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Wycombe Sports Centre, High Wycombe". Willmott Dixon. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ a b Colley, Andrew (19 December 2015). "100 PICTURES: Look back at 40 years of memories as Wycombe Sports Centre closes for the last time". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Public responded well to sports centre display". Bucks Free Press. 25 November 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Farr, Simon (23 January 2014). "Waitrose to open store at Handy Cross?". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Farr, Simon (21 May 2014). "Construction begins on new Wycombe Sports Centre". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Colley, Andrew (5 January 2016). "£25 million Wycombe Leisure Centre opened to the public". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Handy Cross landscape changing once again". building handy x hub. 31 March 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Loakes Park 1947 - A gift to Wycombe Wanderers from Frank Adams". www.chairboys.co.uk. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Ricoh Stadium Move". Wasps RFC. 8 October 2014. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "High Wycombe Cricket Club". highwycombe.play-cricket.com. High Wycombe CC. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Home Counties Premier Cricket". hcpcl.play-cricket.com. HCPCL. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ "Thames Valley Cricket League". thamesvalleycl.play-cricket.com. TVCL. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ "Bucks Cricket Competitions". buckscricketcomps.play-cricket.com. BCC. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ "Mad women, triple poisoners and parallel world portal: High Wycombe". Slow Travel: The Chilterns and Thames Valley. 26 August 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ Sheth Trivedi, Shruti (9 January 2017). "Excited Sherlock fans take to social media after town mentioned on show multiple times". Bucks Free Press. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Chloe Pirrie interview for Black Mirror". www.channel4.com. Channel 4. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2020.