Yvonne Yvette Fontaine (8 August 1913 – 9 May 1996), also known as Yvonne Fauge, code named Nenette and Mimi, was a member of the French Resistance and an agent of the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) organization during World War II. The purpose of SOE was to conduct espionage, sabotage, and reconnaissance in occupied Europe against the Axis powers, especially Nazi Germany. SOE agents allied themselves with resistance groups and supplied them with weapons and equipment parachuted in from England.

Yvonne Fontaine | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | Nenette, Mimi |

| Born | 8 August 1913 Longuyon, France |

| Died | 9 May 1996 (aged 82) France |

| Allegiance | France |

| Service | Special Operations Executive, French Resistance |

| Years of service | 1943-1944 |

| Rank | Field agent (courier) |

| Unit | SOE F Section, Networks Tinker and Minister |

Fontaine worked as a courier for the Tinker and Minister networks (or circuits) in France in 1943 and 1944. She was, in the words of author Beryl E. Escott, "a highly successful and competent agent."[1]

Early life

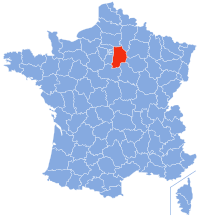

editYvonne Fontaine was born in Longuyon on 8 August 1913. In the early days of World War II, she was described as "twice married, once divorced, and her second husband, an Italian, had disappeared. She was not unhappy about his disappearance. "Vivacious, and smart and worldly" with "no family obligations," she worked as the manager of a dye and dry cleaning company in Troyes.[2] She did not take part in any resistance activities until April 1943. She was anti-German but also criticized the De Gaullist resistance movement as too political, self-seeking, and talkative.[3] As Troyes was an industrial region well connected to Paris, the city was the target of numerous Allied bombings generating numerous pilots and their crews to be hidden when their planes were shot down. Fontaine gradually entered the French Resistance by helping downed airmen evade capture by the Germans.[1]

Special Operations Executive

editTinker network

editFontaine's work with the resistance began in April 1943 when an experienced SOE agent, Benjamin Cowburn, and his radio operator Denis John Barrett came to Troyes to set up a sabotage network, which SOE named Tinker. Cowburn came into contact with Pierre Mulsant and through him met Fontaine who he hired as a courier for a salary of 2,000 francs (about 10 British pounds) per month. Given the code name Nenette, she was adept at the job, carrying messages and sabotage material over a large area in northeastern France. The Tinker network had some successes, including on the night of 3/4 July the destruction of six locomotives used by the Germans. Fontaine also helped eighteen American airmen, shot down near Troyes, escape to Switzerland. However, the Germans infiltrated and destroyed many of the SOE networks in France during the summer of 1943. Cowburn was evacuated from France in September 1943 and on 15 November, the remaining members of the Tinker team, Fontaine, Mulsant, and Barrett, departed France for England from a clandestine airfield. Among the other resistance workers evacuated on the same airplane was a future president of France, François Mitterrand.[4][5]

Minister network

editIn England, Fontaine underwent SOE training.[6] She was known to SOE by her married name of Yvonne Fauge. SOE officials differed in their assessment of her during her training. One trainer of a group of prospective SOE agents said, "she was the most interesting person here and probably the most intelligent. A lively and indefatigable talker." Another said that she was "egocentric, spoilt, stubborn, impatient, conceited..." Fontaine was the only non-English speaker in her group of SOE trainees.[7]

Fortaine returned to France by boat[8] the night of 25 March 1944, landing on a beach in Brittany.[9] She made her way to Paris where she re-united with her friends Pierre Muslant, the organiser (leader) of the new Minister network, and Denis Barrett, the radio operator. Mulsant installed her in a safe house in Melun, about 40 kilometres (25 miles) southeast of Paris. She chose the new code name of Mimi.[10] In addition to her travel as a courier, she located farm fields suitable for air drops of arms and supplies for the French Resistance. She organized groups to receive five air drops in April and May. In April she also met on their arrival by parachute a team of three American military officers who were to work with the French Resistance preparing for D-Day, the allied invasion of France which took place on 6 June 1944. The Minister network was successful in organising and carrying out several small-scale sabotage operations aimed at hindering German logistics[6] and transport of supplies to the battlefields after D-Day.[11]

Disaster struck in July 1944. A British commando team of the SAS called Operation Gain radioed they were in trouble in the nearby Forest of Fontainebleau. Mulsant and Barrett and others rushed to rescue the SAS team but were captured by the Germans. Benjamin Cowburn returned to France on 30 July in an unsuccessful attempt to free Mulsant and Barrett but both were later executed. Fontaine, the sole survivor of the Minister network, continued work with the Resistance until the liberation of the area from German control in late August 1944. She returned by airplane to England on 16 September.[1][12]

Aftermath

editFontaine was bitter about the capture of her colleagues, Mulsant and Barrett, and put her criticisms in a report to SOE. The capture of Mulsant and Barrett, she wrote, "was entirely the fault of sending in SAS parties in uniform in an area which was very closely patrolled by SS troops." The SAS team was able to withdraw to a safe area, but Mulsant and Barrett, attempting to help the SAS team, "were not aware of this" and were captured.[13]

On her return to London, Fontaine was housed in a hotel with two other female SOE agents who also had grievances against the SOE: Anne-Marie Walters and Odette Wilen. An SOE officer reported their indiscreet conversation, openly discussing the arrests of SOE agents. He said of Fontaine, "Her present nervous condition is largely due to the fact that she blames the organization [SOE] for the arrests of her two friends." He added that "I was seriously shocked by the attitude of these three ladies."[14]

Fontaine never received recognition for her work with SOE. SOE's spymaster, Vera Atkins, claimed that Fontaine was recruited in the field and was never an official agent of the French section of SOE.[15][16] Proposals that Fontaine be awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Order of the British Empire were never approved. The de Gaulle government of France did give her the Medal of the Resistance. Despite the sparsity of her recognition, the appraisal by SOE of Fontaine's work was that she was "an efficient and loyal courier and assistant" with a "gift for clandestine work."[17]

After the war Fontaine married a Frenchman named Dupont. She died on 9 May 1996.[17]

Decoration

edit| Médaille de la Résistance |

References

edit- ^ a b c Escott, Beryl E. (2010), The Heroines of SOE, Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, pp. 164–165

- ^ Childers, Thomas (2004), In the Shadows of War, New York: Henry Holt and Company, p. 130

- ^ O'Connor, Bernard (2018), SOE Heroines, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing, p. 273

- ^ O'Connor, (2018), pp. 273-275

- ^ Escott, pp. 162-163

- ^ a b Jacobs, Peter (30 September 2015). Setting France Ablaze: The SOE in France During WWII. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-6662-1.

- ^ O'Connor, (2018), pp. 280-281

- ^ Foot, Michael (1966). SOE in France (PDF). London: HMSO. pp. Appendix B.

- ^ Vigurs, Kate (15 February 2024). Mission France: The True History of the Women of SOE. New York: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-20857-3.

- ^ O'Connor (2018), p. 282.

- ^ Escott, p. 164

- ^ Foot, M.R.D. (1966), SOE in France, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, p. 410

- ^ O'Connor, Bernard (31 October 2016). Agents Francaises. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781326704988. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ O'Connor, p. 284

- ^ Liane Jones, A Quiet Courage: Women Agents in the French Resistance, London, Transworld Publishers Ltd, 1990. ISBN 0-593-01663-7

- ^ Escott, p. 165

- ^ a b O'Connor, p. 287